A STUDY of XU XU's DRAMA SCRIPTS, 1939-1944 by JIAQI YAO MA, Hong Kong University of Science and Techn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

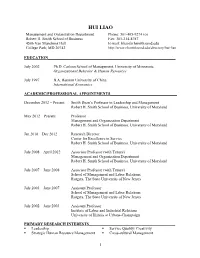

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (O) Robert H

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (o) Robert H. Smith School of Business Fax: 301-214-8787 4506 Van Munching Hall E-mail: [email protected] College Park, MD 20742 http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/directory/hui-liao EDUCATION_________________________________________________________________ July 2002 Ph.D. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota Organizational Behavior & Human Resources July 1997 B.A. Renmin University of China International Economics ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS__________________________________ December 2012 – Present Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland May 2012 – Present Professor Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 Research Director Center for Excellence in Service Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2008 – April 2012 Associate Professor (with Tenure) Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2007 – June 2008 Associate Professor (with Tenure) School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2003 – June 2007 Assistant Professor School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2002 – June 2003 Assistant Professor Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS____________________________________________ . Leadership . Service Quality/ Creativity . Strategic Human Resource Management . Cross-cultural Management 1 MAJOR SCHOLARLY AWARDS AND HONORS__________________________________ . 2012, Named an endowed professorship – Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland . 2012, Cummings Scholarly Achievement Award, OB Division, Academy of Management . -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Rickshaw Boy Free

FREE RICKSHAW BOY PDF Lao She | 300 pages | 07 Sep 2010 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061436925 | English | New York, NY, United States Rickshaw driver's son beats odds to join famed UK ballet school | UK news | The Guardian Kamal Singh did not even know what ballet was when he turned up nervously at the Imperial Fernando Ballet School, in Delhi, during the summer of Rickshaw Boy But the year-old, known as Noddy, whose father was a rickshaw driver in the west of the city, had been transfixed by ballet dancers in a Bollywood film, and wanted to try it for himself. Four years on Singh is now one of the first Indian students Rickshaw Boy be admitted to the English National Ballet school. He started this week. I am the first in my family to come to London. He had a Rickshaw Boy that was ready-made for ballet by god Rickshaw Boy he just needed to be taught how to use it. He studied at the school for 10 to 12 hours every day. I Rickshaw Boy him for four years, and he Rickshaw Boy asked for a break, he never missed a single day. He also made Singh and his family realise that there was a future in ballet. After that my father allowed me to study full-time. He had been granted a scholarship to return this year but the Covid pandemic happened and everything was cancelled. Just as it seemed as if the opportunities were disappearing, an advert on Instagram said that English National Ballet in London was looking for male dancers. -

The Biopolitical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2018 The iopB olitical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds Xiaoyu Gao Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gao, Xiaoyu, "The iopoB litical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds" (2018). Masters Theses. 3619. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3619 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The GraduateSchool � EA'ill 11.'1I·��-- h l:'ll\'tll\11'\' Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate candidates Completing Theses in PartialFulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: •The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. •The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Laughter and the Cosmopolitan Aesthetic in Lao She's 二马 (Mr. Ma

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 1 Article 6 Laughter and the Cosmopolitan Aesthetic in Lao She's ?? (Mr. Ma and Son) Jeffrey Mather City University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Mather, Jeffrey. "Laughter and the Cosmopolitan Aesthetic in Lao She's ?? (Mr. Ma and Son)." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.1 (2014): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2115> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

I Want to Be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition

Volume 6 Issue 1 2020 “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan [email protected] ISSN: 2057-1720 doi: 10.2218/ls.v6i1.2020.4398 This paper is available at: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lifespansstyles Hosted by The University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan The years leading up to the political handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China surfaced issues regarding national identification and intergroup relations. These issues manifested in Hong Kong films of the time in the form of film characters’ language ideologies. An analysis of six films reveals three themes: (1) the assumption of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and Putonghua, (2) the importance of English towards one’s Hong Kong identity, and (3) the expectation that Mainland immigrants use Cantonese as their primary language of communication in Hong Kong. The recurrence of these findings indicates their prevalence amongst native Hongkongers, even in a post-handover context. 1 Introduction The handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 marked the end of 155 years of British colonial rule. Within this socio-political landscape came questions of identification and intergroup relations, both amongst native Hongkongers and Mainland Chinese (Tong et al. 1999, Brewer 1999). These manifest in the attitudes and ideologies that native Hongkongers have towards the three most widely used languages in Hong Kong: Cantonese, English, and Putonghua (a standard variety of Mandarin promoted in Mainland China by the Government). -

The Linguistic Categorization of Deictic Direction in Chinese – with Reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre

The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre To cite this version: Christine Lamarre. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese –. Dan XU. Space in Languages of China, Springer, pp.69-97, 2008, 978-1-4020-8320-4. hal-01382316 HAL Id: hal-01382316 https://hal-inalco.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382316 Submitted on 16 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Lamarre, Christine. 2008. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese — With reference to Japanese. In Dan XU (ed.) Space in languages of China: Cross-linguistic, synchronic and diachronic perspectives. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer, pp.69-97. THE LINGUISTIC CATEGORIZATION OF DEICTIC DIRECTION IN CHINESE —— WITH REFERENCE TO JAPANESE —— Christine Lamarre, University of Tokyo Abstract This paper discusses the linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Mandarin Chinese, with reference to Japanese. It focuses on the following question: to what extent should the prevalent bimorphemic (nondeictic + deictic) structure of Chinese directionals be linked to its typological features as a satellite-framed language? We know from other satellite-framed languages such as English, Hungarian, and Russian that this feature is not necessarily directly connected to satellite-framed patterns. -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine

SAFETY OF CHINESE HERBAL MEDICINE Giovanni Maciocia® Su Wen Press 2003 GIOVANNI MACIOCIA Published in 1999 by Su Wen Press 5 Buckingham House Bois Lane Chesham Bois Buckinghamshire UK Copyright © Giovanni Maciocia All rights reserved, including translation. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means, electronic or mechanical, recording or duplication in any information or storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers, and may not be photocopied or otherwise reproduced even within the terms of any licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd. ISBN 0 9536157 0 7 First edition 1999 Second edition 2000 Third edition 2003 2 GIOVANNI MACIOCIA Contents Page Introduction 4 1. How drugs are metabolized and excreted ........................................................ 5 2. Factors affecting dosage of drugs ........................................................................ 10 3. Description of side-effects, adverse reactions, idiosyncratic ........... 12 reactions and allergic reactions to drugs 4. Differences in the pharmacodynamics of drugs and herbs ................ 14 5. Side-effects, adverse reactions, idiosyncratic reactions ...................... 16 and allergic reactions to herbal medicines: a review of the literature with identification of some mistakes 6. Interactions between drugs and Chinese herbs ......................................... 21 7. Side-effects of Chinese herbal formulae and how .................................... 27 to deal with them 8. Symptoms -

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: a Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: A Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012 The dragon begets dragon, the phoenix begets phoenix, and the son of the rat digs holes in the ground (traditional saying). This paper estimates the rate of intergenerational social mobility in Late Imperial, Republican and Communist China by examining the changing social status of originally elite surnames over time. It finds much lower rates of mobility in all eras than previous studies have suggested, though there is some increase in mobility in the Republican and Communist eras. But even in the Communist era social mobility rates are much lower than are conventionally estimated for China, Scandinavia, the UK or USA. These findings are consistent with the hypotheses of Campbell and Lee (2011) of the importance of kin networks in the intergenerational transmission of status. But we argue more likely it reflects mainly a systematic tendency of standard mobility studies to overestimate rates of social mobility. This paper estimates intergenerational social mobility rates in China across three eras: the Late Imperial Era, 1644-1911, the Republican Era, 1912-49 and the Communist Era, 1949-2012. Was the economic stagnation of the late Qing era associated with low intergenerational mobility rates? Did the short lived Republic achieve greater social mobility after the demise of the centuries long Imperial exam system, and the creation of modern Westernized education? The exam system was abolished in 1905, just before the advent of the Republic. Exam titles brought high status, but taking the traditional exams required huge investment in a form of “human capital” that was unsuitable to modern growth (Yuchtman 2010). -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University.