Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

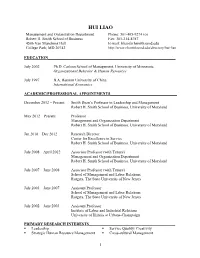

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (O) Robert H

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (o) Robert H. Smith School of Business Fax: 301-214-8787 4506 Van Munching Hall E-mail: [email protected] College Park, MD 20742 http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/directory/hui-liao EDUCATION_________________________________________________________________ July 2002 Ph.D. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota Organizational Behavior & Human Resources July 1997 B.A. Renmin University of China International Economics ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS__________________________________ December 2012 – Present Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland May 2012 – Present Professor Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 Research Director Center for Excellence in Service Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2008 – April 2012 Associate Professor (with Tenure) Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2007 – June 2008 Associate Professor (with Tenure) School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2003 – June 2007 Assistant Professor School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2002 – June 2003 Assistant Professor Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS____________________________________________ . Leadership . Service Quality/ Creativity . Strategic Human Resource Management . Cross-cultural Management 1 MAJOR SCHOLARLY AWARDS AND HONORS__________________________________ . 2012, Named an endowed professorship – Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland . 2012, Cummings Scholarly Achievement Award, OB Division, Academy of Management . -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 3. Before

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 3. Before we pick up where we left off, I have a quick programming note for those of you who haven’t seen it on the website yet. I have decided to scale back the length of the episodes. Each of the first two episodes came in at nearly 40 minutes, and it felt long when I was writing them, recording them, editing them, and listening to them. When I am talking from a script for a long time, I have a tendency to fall back into reading rather than talking, and I want to avoid that. So I am going to try to keep future episodes to between 25 and 30 minutes. I think that will make the episodes easier for me to produce and result in a better product for you. It does mean that it will take longer to get through the whole novel, but hey, when your project starts out being at least a three-year commitment, what’s a few more months? So anyway, back to the story. At the end of the last episode, we were knee-deep in palace intrigue as a power struggle had broken out at the very top of the empire. Emperor Ling had just died. He had two sons, and both them were just kids at this point. The eunuchs were planning to make one son, prince Liu Xie (2), the heir, but the regent marshall, He Jin, the brother of the empress, beat them to the punch and declared her son, prince Liu Bian (4), the new emperor. -

Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Cao Cao Dossier 曹操 Crisis Director: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Email: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Harjot Singh Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: 1. Front Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier (Pages 3-4) 4. Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5. Cao Zhang (Pages 7-8) 6. Cao Zhi (Pages 9-10) 7. Lady Bian (Page 11) 8. Emperor Xian of Han (Pages 12-13) 9. Empress Fu Shou (Pages 14-15) 10. Cao Ren (Pages 16-17) 11. Cao Hong (Pages 18-19) 12. Xun Yu (Pages 20-21) 13. Sima Yi (Pages 22-23) 14. Zhang Liao (Pages 24-25) 15. Xiahou Yuan (Pages 26-27) 16. Xiahou Dun (Pages 28-29) 17. Yue Jin (Pages 30-31) 18. Dong Zhao (Pages 32-33) 19. Xu Huang (Pages 34-35) 20. Cheng Yu (Pages 36-37) 21. Cai Yan (Page 38) 22. Han Ji (Pages 39-40) 23. Su Ze (Pages 41-42) 24. Works Cited (Pages 43-) Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier: Most characters within the Court of Cao Cao are either generals, strategists, administrators, or family members. ● Generals lead troops on the battlefield by both developing successful battlefield tactics and using their martial prowess with skills including swordsmanship and archery to duel opposing generals and officers in single combat. They also manage their armies- comprising of troops infantrymen who fight on foot, cavalrymen who fight on horseback, charioteers who fight using horse-drawn chariots, artillerymen who use long-ranged artillery, and sailors and marines who fight using wooden ships- through actions such as recruitment, collection of food and supplies, and training exercises to ensure that their soldiers are well-trained, well-fed, well-armed, and well-supplied. -

The Zhuan Xupeople Were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia

E-Leader Bangkok 2018 The Zhuan XuPeople were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia Soleilmavis Liu, Author, Board Member and Peace Sponsor Yantai, Shangdong, China Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people (or tribes) in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao.However, the Zhuan Xu People seemed to have disappeared when the Yellow and Chang-jiang river valleys developed into advanced Neolithic cultures. Where had the Zhuan Xu People gone? Abstract: Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of individuals, but also the names of groups who regarded them as common male ancestors. These groups used to live in the Pamirs Plateau, later spread to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. Shanhaijing reveals Zhuan Xu’s offspring lived near the Tibetan Plateau in their early time. They were the first who entered the Tibetan Plateau, but almost perished due to the great environment changes, later moved to the south. Some of them entered the Sichuan Basin and became the founders of Sanxingdui Culture. Some of them even moved to the south of the Tibetan Plateau, living near the sea. Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. Keywords: Shanhaijing; Neolithic China, Zhuan Xu, Sanxingdui, Ancient Chinese Civilization Introduction Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. -

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD -

The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 8, No. 12, pp. 1698-1703, December 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0812.17 The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture Donghui Chen Henan Academy of Social Sciences, Zhengzhou, Henan, China Abstract—Huang Di culture is an important source of Chinese culture. It is not mechanical, still and solidified but melting, extensible, creative, pioneering and vigorous. It is the root of Chinese culture and a cultural system that keeps pace with the times. Its influence is enduring and universal. It has rich connotations including the “Root” Culture, the “Harmony” Culture, the “Golden Mean” Culture, the “Governance” Culture. All these have a great significance for the times and the realization of the Great Chinese Dream, therefore, it is necessary to combine the inheritance of Huang Di culture with its innovation, constantly absorb the fresh blood of the times with a confident, open and creative attitude, give Huang Di culture a rich connotation of the times, tap the factors in Huang Di culture that fit the development of the modern times to advance the progress of the country and society, and make Huang Di culture still full of vitality in the contemporary era. Index Terms—Huang Di, Huang Di culture, Chinese culture I. INTRODUCTION Huang Di, being considered the ancestor of all Han Chinese in Chinese mythology, is a legendary emperor and cultural hero. His victory in the war against Emperor Chi You is viewed as the establishment of the Han Chinese nationality. He has made great many accomplishments in agriculture, medicine, arithmetic, calendar, Chinese characters and arts, among which, his invention of the principles of Traditional Chinese medicine, Huang Di Nei Jing, has been seen as one of the greatest contributions to Chinese medicine. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University.