Yeh-Lü Ch'u-Ts'ai) (1190-1244)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUNY in Nanjing

China Program Description, p. 1 of 5 CUNY-BC Study in China: Program Description & Itinerary Tentative Program Dates: May 30-June 20, 2016 Application Deadline: March 21, 2016 Program Director: Professor Shuming Lu Department of Speech Communication Arts & Sciences Brooklyn College, the City University of New York Telephone: 718-951-5225 E-mail: [email protected] This program is designed in such a way that all travel is education-related. The cities we have chosen to visit are all sites of great historical and cultural importance. 1. Beijing is the current capital of China and used to be the capital of several late Chinese dynasties. Many sites in Beijing (e.g., Tiananmen Square, Palace Museum, Forbidden City, the Great Wall, Summer Palace, the Olympic Stadium) are directly related to what we are teaching in our courses on Chinese history, culture, society, and Chinese business & economy. 2. Xi’an was where Chinese dynasties started several thousand years ago and many subsequent emperors established their capitals. It is also the eastern starting point of the ancient overland Silk Road. Sites that strongly support the academic content of our courses are the Terra Cotta Museum, Qin Shihuangdi Emperor’s Mausoleum, Wild Good Pagoda Buddhist Temple & Square, Xuanzang Buddhist Statue, Silk Road Sites, Tang Dynasty Art Museum, Muslim Quarter, and the Great Mosque. 3. Nanjing was the capital of six ancient Chinese dynasties and the capital of the first Republic of China—a place of great significance in modern Chinese history. Ming Dynasty first established its capital here and then moved the capital to Beijing. -

Robustness Assessment of Urban Rail Transit Based on Complex Network

Safety Science 79 (2015) 149–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Safety Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ssci Robustness assessment of urban rail transit based on complex network theory: A case study of the Beijing Subway ⇑ ⇑ Yuhao Yang a, Yongxue Liu a,b, , Minxi Zhou a, Feixue Li a,b, , Chao Sun a a Department of Geographic Information Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China b Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China article info abstract Article history: A rail transit network usually represents the core of a city’s public transportation system. The overall Received 21 October 2014 topological structures and functional features of a public transportation network, therefore, must be fully Received in revised form 4 April 2015 understood to assist the safety management of rail transit and planning for sustainable development. Accepted 9 June 2015 Based on the complex network theory, this study took the Beijing Subway system (BSS) as an example Available online 23 June 2015 to assess the robustness of a subway network in face of random failures (RFs) as well as malicious attacks (MAs). Specifically, (1) the topological properties of the rail transit system were quantitatively analyzed Keywords: by means of a mathematical statistical model; (2) a new weighted composite index was developed and Rail transit proved to be valid for evaluation of node importance, which could be utilized to position hub stations in a Complex network Robustness subway network; (3) a simulation analysis was conducted to examine the variations in the network per- Scale-free formance as well as the dynamic characteristics of system response in face of different disruptions. -

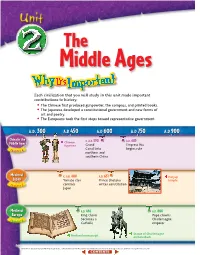

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

Beijing 2022 Press Accommodation Guide

Beijing 2022 Press Accommodation Guide Beijing Organising Committee for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games September, 2020 Beijing 2022 Press Content Accommodation Guide Introduction Policies and Procedures 1 Accreditation Requirement 1 Beijing 2022 Accommodation Booking Period 1 Accommodation Facility Classification System 1 Room Types 2 Room Rates 3 Room Reservation 3 Accommodation Allocation Agreement(AAA) 3 Accommodation Management System (AMS) 4 Reservation Procedure 4 Cancellation Policy 5 Reservation Changes 6 Re-sale 6 Payment 7 Check-in/Check-out Time 8 Deposit 8 Incidental Charges 8 Function Rooms 8 Parking Spaces 8 Accommodation Timeline and Key Dates 8 Press Hotel List 9 Press Hotel Map 10 Hotel Information Sheet 15 Appendix: Beijing 2022 Press Accommodation Request Form 51 Beijing 2022 Press Introduction Accommodation Guide Welcome to the Press Accommodation Guide presented by the Beijing Organising Committee for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games (Beijing 2022). This Guide is intended to assist press to secure accommodation for the Beijing 2022 Olympic Winter Games, please read this guide thoroughly to be able to secure sufficient price-controlled accommodation and assist us to offer the best possible accommodation allocation. To date, Beijing 2022 has contracted around 100 accommodation facilities based on location, transportation, star-rating and service levels. Beijing 2022 provides 18 accommodation facilities with 2,446 rooms for press in Beijing, Yanqing and Zhangjiakou zones. To find more information about the press accommodation facilities, please read the Press Hotel Information Sheet and view the Press Hotels Map. Designating an Accommodation Management System (AMS) authorised person and providing his/her information is the first step to your room reservation. -

Preservation of Lilong Neighborhoods in Shanghai

PRESERVATION OF LILONG NEIGHBORHOODS IN SHANGHAI: SOCIAL CHANGE AND SPATIAL RIGHTS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Historic Preservation Planning by Ran Yan August 2013 © 2013 Ran Yan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT As once the most common form of dwelling in Shanghai, the Lilong has played a vital role in Shanghai’s local culture. Gradually declining in number during the second half of the 20th century, it is now faced with a challenging and undecided future. This thesis aims to further the discussion of the preservation of Lilong neighborhoods in its fundamental relation with people and basic social context. Four case studies, Tian Zi Fang, Jian Ye Li, Jing An Bie Shu and Bu Gao Li, are used to add some realistic, specific details and to deepen the reflection on this topic. Each of the cases has its special architectural features, residential composition, history, and current problems all of which provide some insight into the uniqueness and individuality of every Lilong neighborhood. In the end recommendations are made to address to Lilong residents’ right and to call for an equal way of Lilong preservation as a means to a better living environment for everyone and a more equitable society. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Ran Yan was born on August 9th, 1988 in Beijing, China, where she grew up and finished her early education. In 2011 she received her Bachelor of Engineering degree in Historic Preservation from Tongji University, in Shanghai. With a background in both architecture and historic preservation, she continued on to graduate study in the Historic Preservation Planning program at the City and Regional Planning Department of Cornell University. -

Igor De Rachewiltz

East Asian History NUMBER 31 . J UNE 2006 Institute of Advanced Studies The Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Barme Associate Editors Benjamin Penny Lindy Shultz Business Manager Marion Weeks Editorial Board B0rge Bakken John Clark Helen Dunstan Louise Edwards Mark Elvin John Fitzgerald Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Kenneth Wells Design and Production Oanh Collins, Marion Weeks, Maxine McArthur Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the thirty-first issue of East Asian History, printed in October 2007, in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. This externally refereed journal is published twice a year Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26125 3140 Fax +61 2 6125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address, or to marion. [email protected] Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 iii .4!. CONTENTS 1 Building Warrior Legitimacy in Medieval Kyoto Matthew Stavros 29 Building a Dharma Transmission Monastery in Seventeenth-Century China: The Case of Mount Huangbo Jiang Wu 53 The Genesis of the Name "Yeke Mongyol Ulus"• . Igor de Rachewiltz 57 Confucius in Mongolian: Some Remarks on the Mongol Exegesis of the Analects Igor de Rachewiltz 65 A Note on YeW Zhu I[[H~ S and His Family Igor de Rachewiltz 75 Exhibiting Meiji Modernity: Japanese Art at the Columbian Exposition Judith Snodgrass 101 Turning Historians into Party Scholar-Bureaucrats: North Korean Historiography, 1955-58 Leonid Petrov iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ~~ o~n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Higuchi Haruzane, Tea and Coffee set - "Exhibiting Meiji Modernity: Japanese Art at Columbina Exposition" by Judith Snodgrass, see p.90. -

EWG 19 13A Anx 2 Confirmed Attendees

No. Name Company Name Title Email Phone Address Gender Role Senior Management & 626 Cochrans Mill Road P.O.Box 10940 1 Scott Smouse US DOE;APEC EGCFE [email protected] Male Speaker Technical Advisor OV 202 5866278 Pittsburgh,PA 15236-0940 Andrew 2 (IEA) Clean Coal Centre General Manager Andrew.Minchener@iea- Park House 14 Northfields London SW18 IDD UK Male Speaker Minchener coal.org 44 20 88776280 5th Floor, Heddon House, 149-151 Regent Street, 3 Benjamin Sporton World Coal Association(London) Acting Chief Executive Male Speaker [email protected] 44 2078510052 London, W1B 4JD, UK 3F Daiwa Nishi-shimbashi Building 3-2-1 Nishi- 4 Keiji Makino Japan coal energy center Professor Male Speaker [email protected] 8 13 64026101 Shimbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 Japan 1300 West W. T. Harris Blvd, Charlotte, NC 5 Jeffrey N. Phillips EPRI Sr. Program Mgr Male Speaker [email protected] 1 704 9414188 28262, USA 26th Floor FFC No.5 North 3rd Ring Road, 6 Murray Mortson Airbone President m.mortson@airbornecleanen Male Speaker ergy.com 86 13466688305 Chaoyang District, Beijing 26th Floor FFC No.5 North 4rd Ring Road, 7 Michael Zhao Airbone CEO Male Participant [email protected] 86 13910538135 Chaoyang District, Beijing Forest Power & Energy Holdings, 2nd Floor No 7 Building YuquanHuigu No 3 8 Croll Xue Vice-president Male Participant Inc. [email protected] 86 13321156701 Minzhuang Road Haidian District Beijing Forest Power & Energy Holdings, 2nd Floor No 7 Building YuquanHuigu No 3 9 Mingtao Zhu Senior manager Male Participant Inc. [email protected] 86 13901383638 Minzhuang Road Haidian District Beijing 10 Daming Yang CARE-Gen, LLC.(GP Strategies) President Male Speaker [email protected] 86 18515099980 Shijingshan District, Beijing Rm K-M, 7/F, Tower A, The East Gate Plaza, #9 11 Xiaoliang Yang World Resources Institute Research Analyst Male Participant [email protected] 86 18510568512 Dongzhong Street, Beijing, China, 100027 Manager (Energy & Hongkong Electric Centre, 44 Kennedy Road, 12 Mr. -

CAA-Certified Auction Houses

China’s Arts & Antiques Auction Standardization Qualified/Exemplary Auction Houses (2014) No. Auction House Name City 1 Beijing ChengXuan Auctions Co., Ltd. Beijing 2 Beijing Chieftown Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 3 Beijing CNTC International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 4 Beijing Council International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 5 Beijing Debao International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 6 Beijing Hanhai Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 7 Beijing Reaping Auctions Co., Ltd. Beijing 8 Beijing Zhongpai International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 9 China Guardian Auctions Co., Ltd. Beijing 10 Huachen Auctions Beijing 11 Inzone International Auctions Co., Ltd. Beijing 12 Pacific International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 13 Poly International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 14 Rombon Auction Beijing Beijing 15 Sotheby’s Beijing Beijing 16 Sungari International Auction Beijing 17 Zhongdu International Auction Co., Ltd. Beijing 18 Sichuan Jiacheng Auction Co., Ltd. Chengdu 19 Chongqing Hengsheng Auction Co., Ltd. Chongqing 20 Chongqing Hua Xia Wen Wu Auction Co., Ltd. Chongqing 21 Fujian Maoyi Xintuo Auction Fuzhou 22 Guangdong Chongzheng Auction Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 23 Guangdong Gujin Auction Co., Ltd. Guangzhou No. Auction House Name City 24 Guangdong Hengyi Auction Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 25 Guangdong Provincial Auctioneers Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 26 Guangzhou Huangma Auction Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 27 Guangzhou Yintong Auction Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 28 Holly International Auctions Co., Ltd. Guangzhou 29 XiLingYinShe Auction Co. Ltd. Hangzhou 30 Zhejiang International Commodity Auction Co., Ltd. Hangzhou 31 Zhejiang Jiabao Auction Co., Ltd. Hangzhou 32 Zhejiang Sanjiang Auction Co., Ltd Hangzhou 33 Anhui Panlong Auction Co., Ltd. Hefei 34 Future Sifang Auction Lanzhou 35 Jiangsu Artall Auction Co., Ltd. -

3 · Reinterpreting Traditional Chinese Geographical Maps

3 · Reinterpreting Traditional Chinese Geographical Maps CORDELL D. K. YEE My interest in this chapter and the following four is tra frames in mind. These extended inquiries are obtained ditional Chinese geographic mapping-that is, Chinese at some cost, however. With a thematic approach one mapping of the earth before its Westernization in the late risks losing a clear sense of chronology, and one sacrifices nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of the first the power of narrative to maintain a sense of direction. lessons one learns when studying this subject is that the By keeping the focus on ideas or themes, one also risks traditional periodization used in scholarship is unsatis losing sight of the maps themselves. Detailed descriptions factory. The traditional scheme takes the rise and fall of of artifacts can disrupt the flow of an argument or at least China's ruling houses as constituting distinct periods (see make it harder to follow, and so in the thematic chapters table 2.1). Such a scheme may have been useful for orga that follow this one, artifacts are dealt with in only as nizing material dealing with political and institutional his much detail as is necessary to support the arguments pre tory, and as will be seen in a later chapter, cartography sented. was intimately connected to that history. But carto The loss of chronology and detail would be regret graphic developments do not neatly parallel changes in table, especially when at least part of the audience for politics. Historians of cartography in the past, however, this book-collectors and cartobibliographers, for exam have tried to tie cartography to dynastic changes in ways ple-could reasonably be expected to take an interest in I have found misleading. -

The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in the Planning of Ming Beijing

Nexus Network Journal https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-021-00555-y RESEARCH The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in the Planning of Ming Beijing Norma Camilla Baratta1 · Giulio Magli2 Accepted: 19 April 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Present day Beijing developed on the urban layout of the Ming capital, founded in 1420 over the former city of Dadu, the Yuan dynasty capital. The planning of Ming Beijing aimed at conveying a key political message, namely that the ruling dynasty was in charge of the Mandate of Heaven, so that Beijing was the true cosmic centre of the world. We explore here, using satellite imagery and palaeomagnetic data analysys, symbolic aspects of the planning of the city related to astronomical alignments and to the feng shui doctrine, both in its “form” and “compass” schools. In particular, we show that orientations of the axes of the “cosmic” temples and of the Forbidden City were most likely magnetic, while astronomy was used in topographical connections between the temples and in the plan of the Forbidden City in itself. Keywords Archaeoastronomy of Ming Beijing · Forbidden City · Form feng shui · Compass feng shui · Ancient Chinese urban planning · Temple design Introduction In the second half of the fourteenth century, China sat in rebellion against the foreign rule of the Mongols, the Yuan dynasty. Among the rebels, an outstanding personage emerged: Zhu Yuanzhang, who succeeded in expelling the foreigners, proclaiming in 1368 the beginning of a new era: the Ming dynasty (Paludan 1998). Zhu took the reign title of Hongwu and made his capital Nanjing. -

Celebrating Traces of History Through Public Open Space Design in Beijing, China a Creative Project Submitted to the Graduate Sc

CELEBRATING TRACES OF HISTORY THROUGH PUBLIC OPEN SPACE DESIGN IN BEIJING, CHINA A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE BY LIN WANG CARLA CORBIN – COMMITTEE CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2014 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the three committee members of my creative project—Ms. Carla Corbin, Mr. Robert C. Baas, and Dr. Francis Parker—for their support, patience, and guidance. Especially Ms. Corbin, my committee chair, encouraged and guided me to develop this creative project. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Geralyn Strecker for her patience and assistance in my writing process. My thanks also extended to Dr. Bo Zhang—a Chinese Professor—who helped me figure out issues between Chinese and American culture. I would also like to express my gratitude to the faculty of the College of Architecture and Planning from whom I learned so much. Finally, special thanks to my family and friends for their love and encouragement during such a long process. The project would not have been completed without all your help. TABLE OF CONTENT CHAPTER1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Subproblems .................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter Three Beijing: an Imperial Ideal City History the Foundation of the Present City Was Laid Over Seven Hundred Years

Chapter Three Beijing: an Imperial Ideal City History The foundation of the present city was laid over seven hundred years. The earliest predecessor of Beijing was the primitive town of Ji, capital of Yan in the 11th century. Its location is now the northwest corner of the present Outer City. In 936, it was captured by the Liao (907-1125), who made it the secondary capital and renamed it Nanjing. After 1125, the Jin emperors made it their residence and enlarged the city, which they called Zhongdu, toward the east. Extensive rebuilding was carried out under the Jin, and grand palaces were erected. (Figure 3.3) The Mongols conquered the city in 1215 and burned the palaces. In 1264, a new capital city was rebuilt by the Mongols called Dadu (The Great Capital). The scheme of the new city plan was very close to the ancient rules set forth by the Chinese philosophers. It was rectangular in shape, with two gates to the north and three gates on each of the other three sides. Broad, straight roads ran between opposite pairs of gates, and the principal streets formed a chessboard design. Two important groups of buildings outside the imperial city were built according to philosopher’s plan : the temple of Ancestor inside the south gate of the east wall, and the Altar of earth and Grain inside the south gate of the west wall (Figure 3.1). The Ming Dynasty founded in 1368 had its first capital at present-day Nanjing. In 1421, the Ming emperor moved to Beijing. New palaces were built on the site of the old palace of Dad.