Preservation of Lilong Neighborhoods in Shanghai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Studies in Central & East Asian Religions Volume 9 1996

Studies in Central & East Asian Religions Volume 9 1996 CONTENTS Articles Xu WENKAN: The Tokharians and Buddhism……………………………………………... 1 Peter SCHWEIGER: Schwarze Magie im tibetischen Buddhismus…………………….… 18 Franz-Karl EHRHARD: Political and Ritual Aspects of the Search for Himalayan Sacred Lands………………………………………………………………………………. 37 Gabrielle GOLDFUβ: Binding Sūtras and Modernity: The Life and Times of the Chinese Layman Yang Wenhui (1837–1911)………………………………………………. 54 Review Article Hubert DECLEER: Tibetan “Musical Offerings” (Mchod-rol): The Indispensable Guide... 75 Forum Lucia DOLCE: Esoteric Patterns in Nichiren’s Thought…………………………………. 89 Boudewijn WALRAVEN: The Rediscovery of Uisang’s Ch’udonggi…………………… 95 Per K. SØRENSEN: The Classification and Depositing of Books and Scriptures Kept in the National Library of Bhutan……………………………………………………….. 98 Henrik H. SØRENSEN: Seminar on the Zhiyi’s Mohe zhiguan in Leiden……………… 104 Reviews Schuyler Jones: Tibetan Nomads: Environment, Pastoral Economy and Material Culture (Per K. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………. 106 [Ngag-dbang skal-ldan rgya-mtsho:] Shel dkar chos ’byung. History of the “White Crystal”. Religion and Politics of Southern La-stod. Translated by Pasang Wangdu and Hildegard Diemberger (Per K. Sørensen)………………………………………… 108 Blondeau, Anne-Marie and Steinkellner, Ernst (eds.): Reflections of the Mountains. Essays on the History and Social Meaning of the Cult in Tibet and the Himalayas (Per K. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………………. 110 Wisdom of Buddha: The Saṃdhinirmocana Mahāyāna Sūtra (Essential Questions and Direct Answers for Realizing Enlightenment). Transl. by John Powers (Henrik H. Sørensen)………………………………………………. 112 Japanese Popular Deities in Prints and Paintings: A Catalogue of the Exhibition (Henrik H. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………………. 113 Stephen F. Teiser, The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism (Henrik H. -

CUNY in Nanjing

China Program Description, p. 1 of 5 CUNY-BC Study in China: Program Description & Itinerary Tentative Program Dates: May 30-June 20, 2016 Application Deadline: March 21, 2016 Program Director: Professor Shuming Lu Department of Speech Communication Arts & Sciences Brooklyn College, the City University of New York Telephone: 718-951-5225 E-mail: [email protected] This program is designed in such a way that all travel is education-related. The cities we have chosen to visit are all sites of great historical and cultural importance. 1. Beijing is the current capital of China and used to be the capital of several late Chinese dynasties. Many sites in Beijing (e.g., Tiananmen Square, Palace Museum, Forbidden City, the Great Wall, Summer Palace, the Olympic Stadium) are directly related to what we are teaching in our courses on Chinese history, culture, society, and Chinese business & economy. 2. Xi’an was where Chinese dynasties started several thousand years ago and many subsequent emperors established their capitals. It is also the eastern starting point of the ancient overland Silk Road. Sites that strongly support the academic content of our courses are the Terra Cotta Museum, Qin Shihuangdi Emperor’s Mausoleum, Wild Good Pagoda Buddhist Temple & Square, Xuanzang Buddhist Statue, Silk Road Sites, Tang Dynasty Art Museum, Muslim Quarter, and the Great Mosque. 3. Nanjing was the capital of six ancient Chinese dynasties and the capital of the first Republic of China—a place of great significance in modern Chinese history. Ming Dynasty first established its capital here and then moved the capital to Beijing. -

Robustness Assessment of Urban Rail Transit Based on Complex Network

Safety Science 79 (2015) 149–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Safety Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ssci Robustness assessment of urban rail transit based on complex network theory: A case study of the Beijing Subway ⇑ ⇑ Yuhao Yang a, Yongxue Liu a,b, , Minxi Zhou a, Feixue Li a,b, , Chao Sun a a Department of Geographic Information Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China b Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China article info abstract Article history: A rail transit network usually represents the core of a city’s public transportation system. The overall Received 21 October 2014 topological structures and functional features of a public transportation network, therefore, must be fully Received in revised form 4 April 2015 understood to assist the safety management of rail transit and planning for sustainable development. Accepted 9 June 2015 Based on the complex network theory, this study took the Beijing Subway system (BSS) as an example Available online 23 June 2015 to assess the robustness of a subway network in face of random failures (RFs) as well as malicious attacks (MAs). Specifically, (1) the topological properties of the rail transit system were quantitatively analyzed Keywords: by means of a mathematical statistical model; (2) a new weighted composite index was developed and Rail transit proved to be valid for evaluation of node importance, which could be utilized to position hub stations in a Complex network Robustness subway network; (3) a simulation analysis was conducted to examine the variations in the network per- Scale-free formance as well as the dynamic characteristics of system response in face of different disruptions. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Chinese Herbal Medicine for Endometriosis (Review)

Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis (Review) Flower A, Liu JP, Chen S, Lewith G, Little P This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 3 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis (Review) Copyright © 2009 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 2 BACKGROUND .................................... 3 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 4 METHODS ...................................... 4 RESULTS....................................... 5 Figure1. ..................................... 7 Figure2. ..................................... 8 DISCUSSION ..................................... 10 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 11 REFERENCES ..................................... 11 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 17 DATAANDANALYSES. 27 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 1 Symptomatic relief. 28 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 2 Symptomatic relief rate (intention-to-treat). 29 Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 CHM versus gestrinone, Outcome 3 Pregnant rate (accumulated from 3-24 months of follow- up)...................................... 29 Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 CHM versus danazol, Outcome 1 Symptomatic relief. 30 Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 -

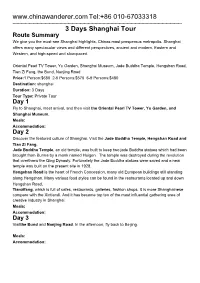

3 Days Shanghai Tour Route Summary We Give You the Must-See Shanghai Highlights, Chinas Most Prosperous Metropolis

www.chinawanderer.com Tel:+86 010-67033318 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 3 Days Shanghai Tour Route Summary We give you the must-see Shanghai highlights, Chinas most prosperous metropolis. Shanghai offers many spectacular views and different perspectives, ancient and modern, Eastern and Western, and high-speed and slow-paced. Oriental Pearl TV Tower, Yu Garden, Shanghai Museum, Jade Buddha Temple, Hengshan Road, Tian Zi Fang, the Bund, Nanjing Road Price:1 Person:$680 2-5 Persons:$570 6-9 Persons:$480 Destination: shanghai Duration: 3 Days Tour Type: Private Tour Day 1 Fly to Shanghai, meet arrival, and then visit the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, Yu Garden, and Shanghai Museum. Meals: Accommodation: Day 2 Discover the featured culture of Shanghai. Visit the Jade Buddha Temple, Hengshan Road and Tian Zi Fang. Jade Buddha Temple, an old temple, was built to keep two jade Buddha statues which had been brought from Burma by a monk named Huigen. The temple was destroyed during the revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty. Fortunately the Jade Buddha statues were saved and a new temple was built on the present site in 1928. Hengshan Road is the heart of French Concession, many old European buildings still standing along Hengshan. Many various food styles can be found in the restaurants located up and down Hengshan Road. Tianzifang, which is full of cafes, restaurants, galleries, fashion shops. It is more Shanghainese compare with the Xintiandi. And it has become top ten of the most influential gathering area of creative industry in Shanghai. Meals: Accommodation: Day 3 Visitthe Bund and Nanjing Road. In the afternoon, fly back to Beijing. -

March 2020 Show Some Legs …

CHINAINSIGHT Fostering business and cultural harmony between China and the U.S. VOL. 19 NO. 3 March 2020 Show some legs … News, p. 3 Business & Economy, p. 5 History, p. 7 Shake. Stomp. Tap. Get those legs a-moving! What’s going on? New line dance at the gym? The Asian version of the Macarena? Whose behind this? Hint: see page 16. Community Society, p. 10 Snuff said! By Margaret Wong, Chinese Heritage Foundation Friends; contributor The first Liu’s perhaps surprising subject was corner from the Scholar’s Study for those Sunday Tea Mia’s collection of Chinese snuff bottles. of you familiar with the Museum’s layout). of 2020 pre- Originally a utilitarian personal accessory He titled this exhibit “Worlds in Miniature.” sented by Chi- for carrying snuff (powered tobacco), they These examples were the subject of the Feb. nese Heritage became an object of display for Chinese 16 talk and Powerpoint slide show. Foundation gentlemen of means. The art form began We learned that we can approach Chi- Arts & Culture , p. 14 Friends on in the 18th century when taking snuff by nese snuff bottles on many different levels. In This Issue Feb. 16 was way of the nose became fashionable in For example, we could begin by cataloging a fascinat- China. The practice of the art flourished the varied materials and techniques that have Arts & Culture 14 ing scholarly into the first half of the 20th century, and is been used. While most of us today associate Books 13 exploration still practiced, and the works are certainly snuff bottles with reverse (interior) painting Business & Economy 5 of what you collected, to this day. -

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Research on the Time When Ping Split Into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect

Chinese Studies 2014. Vol.3, No.1, 19-23 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2014.31005 Research on the Time When Ping Split into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect Ma Chuandong1*, Tan Lunhua2 1College of Fundamental Education, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China 2Sichuan Science and Technology University for Employees, Chengdu, China Email: *[email protected] Received January 7th, 2014; revised February 8th, 2014; accepted February 18th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Ma Chuandong, Tan Lunhua. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Ma Chuandong, Tan Lun- hua. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. The phonetic phenomenon “ping split into yin and yang” 平分阴阳 is one of the most important changes of Chinese tones in the early modern Chinese, which is reflected clearly in Zhongyuan Yinyun 中原音韵 by Zhou Deqing 周德清 (1277-1356) in the Yuan Dynasty. The authors of this paper think the phe- nomenon “ping split into yin and yang” should not have occurred so late as in the Yuan Dynasty, based on previous research results and modern Chinese dialects, making use of historical comparative method and rhyming books. The changes of tones have close relationship with the voiced and voiceless initials in Chinese, and the voiced initials have turned into voiceless in Song Dynasty, so it could not be in the Yuan Dynasty that ping split into yin and yang, but no later than the Song Dynasty.