The Role of Astronomy and Feng Shui in the Planning of Ming Beijing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. Explore ONLINE! SS.912.W.2.19 Describe the impact of Japan’s physiography on its economic and political development. SS.912.W.2.20 Summarize the major cultural, economic, political, and religious developments VIDEOS, including... in medieval Japan. SS.912.W.2.21 Compare Japanese feudalism with Western European feudalism during • A Mongol Empire in China the Middle Ages. SS.912.W.2.22 Describe Japan’s cultural and economic relationship to China and Korea. • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare SS.912.G.2.1 Identify the physical characteristics and the human characteristics that define and differentiate regions. SS.912.G.4.9 Use political maps to describe the change in boundaries and governments within • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind continents over time. and Waves • Marco Polo: Journey to the East • Rise of the Samurai Class • Lost Spirits of Cambodia • How the Vietnamese Defeated the Mongols Document Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Image with Hotspots: A Mighty Fighting Force Image with Hotspots: Women of the Heian Court 78 Module 3 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 600–1400 Explore ONLINE! East and Southeast Asia World 600 618 Tang Dynasty begins 289-year rule in China. -

Olympic Cities Chapter 7

Chapter 7 Olympic Cities Chapter 7 Olympic Cities 173 Section I Host City — Beijing Beijing, the host city of the Games of the XXIX Olympiad, will also host the 13th Paralympic Games. In the year 2008, Olympic volunteers, as ambassadors of Beijing, will meet new friends from throughout the world. The Chinese people are eager for our guests to learn about our city and the people who live here. I. Brief Information of Beijing Beijing, abbreviated“ JING”, is the capital of the People’s Republic of China and the center of the nation's political, cultural and international exchanges. It is a famous city with a long history and splendid culture. Some 500,000 years ago, Peking Man, one of our forefathers, lived in the Zhoukoudian area of Beijing. The earliest name of Beijing 174 Manual for Beijing Olympic Volunteers found in historical records is“JI”. In the eleventh century the state of JI was subordinate to the XI ZHOU Dynasty. In the period of“ CHUN QIU” (about 770 B.C. to 477 B.C.), the state of YAN conquered JI, moving its capital to the city of JI. In the year 938 B.C., Beijing was the capital of the LIAO Dynasty (ruling the northern part of China at the time), and for more than 800 years, the city became the capital of the Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. The People’s Republic of China was established on October 1, 1949, and Beijing became the capital of this new nation. Beijing covers more than 16,000 square kilometers and has 16 subordinate districts (Dongcheng, Xicheng, Chongwen, Xuanwu, Chaoyang, Haidian, Fengtai, Shijingshan, Mentougou, Fangshan, Tongzhou, Shunyi, Daxing, Pinggu, Changping and Huairou) and 2 counties (Miyun and Yanqing). -

Building Railways in the People's Republic of China: Changing Lives

Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China Changing Lives Manmohan Parkash EARD Special Studies Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China: Changing Lives Manmohan Parkash © 2008 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the Philippines Publication Stock No. 092007 ISBN No. 978-971-561645-4 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank, of its Board of Governors, or of the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. ii Building Railways in the People’s Republic of China: Changing Lives Contents Contents .................................................................................. iii List of Tables and Figures .................................................................. iv Abbreviations and Acronyms .............................................................. v Acknowledgement ........................................................................ vi Foreword .................................................................................. vii Executive Summary ....................................................................... viii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... -

Beijing – Forbidden City Maps

Beijing – Forbidden City Maps Forbidden City is the top attraction in Beijing and China plus the world’s most visited site. Imperial City was the domain of 24 Ming and Qing dynasty emperors before becoming the Palace Museum in 1925. Within 180 acres are nearly 1,000 historical palatial structures. Entrance: Meridian Gate, Dongcheng Qu, Donghuamen Rd, Beijing Shi, China, 100006 Also print the travel guide with photos and descriptions. ENCIRCLE PHOTOS © 2017 Richard F. Ebert All Rights Reserved. 1 Beijing – Forbidden City Map Also print travel guide with photos and descriptions. ENCIRCLE PHOTOS © 2017 Richard F. Ebert All Rights Reserved 2 Forbidden City – Outer Court Map Also print travel guide with photos and descriptions. ENCIRCLE PHOTOS © 2017 Richard F. Ebert All Rights Reserved 3 Forbidden City – Inner Court Map Also print travel guide with photos and descriptions. ENCIRCLE PHOTOS © 2017 Richard F. Ebert All Rights Reserved 4 1 Description of Forbidden City 14 Hall of Preserving Harmony Dragons 27 Pavilion at Jingshan Park 2 Tips for Visiting Forbidden City 15 Lions at Gate of Heavenly Purity 28 Northeast Corner Tower 3 Southeast Corner Tower 16 Palace of Heavenly Purity 4 Meridian Gate 17 Palace of Heavenly Purity Throne 5 History of Emperors 18 Grain Measure 6 Gate of Supreme Harmony 19 Bronze Turtle 7 Hall of Supreme Harmony Courtyard 20 Halls of Union and Earthly Tranquility 8 Belvedere of Embodying Benevolence 21 Hall of Imperial Peace 9 Hall of Supreme Harmony 22 400 Year Old Lianli Tree 10 Hall of Supreme Harmony Profile 23 Incense Burner 11 Two Great Halls in Outer Court 24 Springtime Pavilion 12 Houyou Men Gate 25 Autumn Pavilion 13 Gate of Heavenly Purity 26 Autumn Pavilion Ceiling Also print travel guide with photos and descriptions. -

Sarah Provancher Jeanne Hilt (502) 439-7138 (502) 614-4122 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Tuesday, June 5, 2018 CONTACT: Sarah Provancher Jeanne Hilt (502) 439-7138 (502) 614-4122 [email protected] [email protected] DOWNTOWN TO SHOWCASE FÊTE DE LA MUSIQUE LOUISVILLE ON JUNE 21 ST Downtown Louisville to celebrate the Summer Solstice with live music and more than 30 street performers for a day-long celebration of French culture Louisville, KY – A little taste of France is coming to Downtown Louisville on the summer solstice, Thursday, June 21st, with Fête de la Musique Louisville (pronounced fet de la myzic). The event, which means “celebration of music” in French, has been taking place in Paris on the summer solstice since 1982. Downtown Louisville’s “celebration of music” is presented by Alliance Francaise de Louisville in conjunction with the Louisville Downtown Partnership (LDP). Music will literally fill the downtown streets all day on the 21st with dozens of free live performances over the lunchtime hour and during a special Happy Hour showcase on the front steps of the Kentucky Center from 5:30-7:30pm. A list of performance venues with scheduled performers from 11am-1pm are: Fourth Street Live! – Classical musicians including The NouLou Chamber Players, 90.5 WUOL Young Musicians and Harin Oh, GFA Youth Guitar Summit Kindred Plaza – Hewn From The Mountain, a local Irish band 400 W. Market Plaza – FrenchAxe, a French band from Cincinnati Old Forester Distillery – A local jug band The salsa band Milenio is the scheduled performance group for the Happy Hour also at Fourth Street Live! from 5 – 7 pm. "In Paris and throughout France, the Fête de la Musique is literally 24 hours filled with music by all types of musicians of all skill levels. -

Regents and Midterm Prep Answers

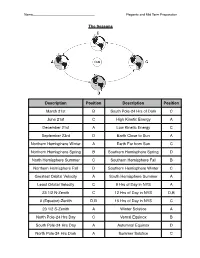

Name__________________________________!Regents and Mid Term Preparation The Seasons Description Position Description Position March 21st B South Pole-24 Hrs of Dark C June 21st C High Kinetic Energy A December 21st A Low Kinetic Energy C September 23rd D Earth Close to Sun A Northern Hemisphere Winter A Earth Far from Sun C Northern Hemisphere Spring B Southern Hemisphere Spring D North Hemisphere Summer C Southern Hemisphere Fall B Northern Hemisphere Fall D Southern Hemisphere Winter C Greatest Orbital Velocity A South Hemisphere Summer A Least Orbital Velocity C 9 Hrs of Day in NYS A 23 1/2 N-Zenith C 12 Hrs of Day in NYS D,B 0 (Equator)-Zenith D,B 15 Hrs of Day in NYS C 23 1/2 S-Zenith A Winter Solstice A North Pole-24 Hrs Day C Vernal Equinox B South Pole-24 Hrs Day A Autumnal Equinox D North Pole-24 Hrs Dark A Summer Solstice C Name__________________________________!Regents and Mid Term Preparation Sunʼs Path in NYS 1. What direction does the sun rise in summer? _____NE___________________ 2. What direction does the sun rise in winter? _________SE_________________ 3. What direction does the sun rise in fall/spring? ________E_______________ 4. How long is the sun out in fall/spring? ____12________ 5. How long is the sun out in winter? _________9______ 6. How long is the sun out in summer? ________15_______ 7. What direction do you look to see the noon time sun? _____S________ 8. What direction do you look to see polaris? _______N_________ 9. From sunrise to noon, what happens to the length of a shadow? ___SMALLER___ 10. -

A Case Study of Donald Trump's First Visit to China

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CSCanada.net: E-Journals (Canadian Academy of Oriental and Occidental Culture, Canadian Research & Development Center of Sciences and Cultures) ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 14, No. 4, 2018, pp. 74-82 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10684 www.cscanada.org Intercultural Communication Strategies in Diplomatic Relations: A Case Study of Donald Trump’s First Visit to China MENG Qingliang[a],[b],* [a]College of Applied Technology, Jiaxing University, Jiaxing, China. Jinping in Forbidden City. The visit was a great success [b] School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, University College for both parties, not only for signing business deals with Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. *Corresponding author. a total value of more than US$ 250bn, but reaching agreements on a series of issues. Received 10 September 2018; accepted 20 November 2018 Published online 26 December 2018 The visit grabbed world attention with wide coverage. The two countries are typical representatives of their respective social systems, with China a socialist country Abstract and the USA a capitalist country; the two countries are This paper explores the intercultural communication the first and second largest economic entities in the world, strategies adopted respectively by Chinese President Xi with China the largest developing country and USA the Jinping and United States’ President Donald Trump during largest developed country. In particular, they represent the latter’s first state visit to China. Based on Hofstede’s two quite different cultures, the oriental and occidental theory of cultural dimensions and Hall’s theory of high- cultures. -

CUNY in Nanjing

China Program Description, p. 1 of 5 CUNY-BC Study in China: Program Description & Itinerary Tentative Program Dates: May 30-June 20, 2016 Application Deadline: March 21, 2016 Program Director: Professor Shuming Lu Department of Speech Communication Arts & Sciences Brooklyn College, the City University of New York Telephone: 718-951-5225 E-mail: [email protected] This program is designed in such a way that all travel is education-related. The cities we have chosen to visit are all sites of great historical and cultural importance. 1. Beijing is the current capital of China and used to be the capital of several late Chinese dynasties. Many sites in Beijing (e.g., Tiananmen Square, Palace Museum, Forbidden City, the Great Wall, Summer Palace, the Olympic Stadium) are directly related to what we are teaching in our courses on Chinese history, culture, society, and Chinese business & economy. 2. Xi’an was where Chinese dynasties started several thousand years ago and many subsequent emperors established their capitals. It is also the eastern starting point of the ancient overland Silk Road. Sites that strongly support the academic content of our courses are the Terra Cotta Museum, Qin Shihuangdi Emperor’s Mausoleum, Wild Good Pagoda Buddhist Temple & Square, Xuanzang Buddhist Statue, Silk Road Sites, Tang Dynasty Art Museum, Muslim Quarter, and the Great Mosque. 3. Nanjing was the capital of six ancient Chinese dynasties and the capital of the first Republic of China—a place of great significance in modern Chinese history. Ming Dynasty first established its capital here and then moved the capital to Beijing. -

Robustness Assessment of Urban Rail Transit Based on Complex Network

Safety Science 79 (2015) 149–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Safety Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ssci Robustness assessment of urban rail transit based on complex network theory: A case study of the Beijing Subway ⇑ ⇑ Yuhao Yang a, Yongxue Liu a,b, , Minxi Zhou a, Feixue Li a,b, , Chao Sun a a Department of Geographic Information Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China b Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210023, PR China article info abstract Article history: A rail transit network usually represents the core of a city’s public transportation system. The overall Received 21 October 2014 topological structures and functional features of a public transportation network, therefore, must be fully Received in revised form 4 April 2015 understood to assist the safety management of rail transit and planning for sustainable development. Accepted 9 June 2015 Based on the complex network theory, this study took the Beijing Subway system (BSS) as an example Available online 23 June 2015 to assess the robustness of a subway network in face of random failures (RFs) as well as malicious attacks (MAs). Specifically, (1) the topological properties of the rail transit system were quantitatively analyzed Keywords: by means of a mathematical statistical model; (2) a new weighted composite index was developed and Rail transit proved to be valid for evaluation of node importance, which could be utilized to position hub stations in a Complex network Robustness subway network; (3) a simulation analysis was conducted to examine the variations in the network per- Scale-free formance as well as the dynamic characteristics of system response in face of different disruptions. -

Chinese Architecture China Has Maintained the Highest Degree of Cultural Continuity Across Its 4000 Years of Existence

Chinese Architecture China has maintained the highest degree of cultural continuity across its 4000 years of existence. Its architectural traditions were very stable until the 19th c. China’s strong central authority is reflected in the Great Wall and standard dimensions for construction. Since the Tang Dynasty (7th-10th c.), Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Neolithic Houses at Banpo, ca 2000 BCE These dwellings used readily available materials—wood, thatch, and earth— to provide shelter. A central hearth is also part of many houses. The rectangular houses were sunk a half story into the ground. The Great Wall of China, 221 BCE-1368 CE. 19-39’ in height and 16’ wide. Almost 4000 miles long. Begun in pieces by feudal lords, unified by the first Qin emperor and largely rebuilt and extended during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) Originally the great wall was made with rammed earth but during the Ming Dynasty its height was raised and it was cased with bricks or stones. https://youtu.be/o9rSlYxJIIE 1;05 Deified Lao Tzu. 8th - 11th c. Taoism or Daoism is a Chinese mystical philosophy traditionally founded by Lao-tzu in the sixth century BCE. It seeks harmony of human action and the world through study of nature. It tends to emphasize effortless Garden of the Master of the action, "naturalness", simplicity Fishing Nets in Suzhou, 1140. and spontaneity. Renovated in 1785 Life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don’t resist them – that only creates sorrow. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

5 China Dreaming

5 China Dreaming Representing the Perfect Present, Anticipating the Rosy Future Stefan Landsberger Abstract As China has developed into a relatively well-offf, increasingly urbanized nation, educating the people has become more urgent than ever. Rais- ing (human) quality (素质) has become a major concern for educators and intellectuals who see moral education as a major task of the state. The visual exhortations in public spaces aimed at moral education are dominated by dreaming about a nation that has risen and needs to be taken seriously. The visualization of these dreams resembles commercial advertising, mixing elements like the Great Wall or the Tiananmen Gate building with modern or futuristic images. This chapter focuses on posters, looking at the changes in contents and representation of government visuals in an increasingly urbanized and media-literate society. Keywords: visual propaganda; governmentality; normative propaganda; Chinese Dream; Beijing Olympics 2008 Sometimes one still encounters hand-painted faded slogans in the coun- tryside urging those working in agriculture to learn from Dazhai, or to energetically study Mao Zedong Thought. By and large, political messages and the images they use have disappeared from Chinese public spaces, in particular in urban areas. Yet, the production of these images, of what we would call propaganda, has not stopped; the government remains com- mitted to educating the people, as it has over the millennia. Compared to the fijirst three decades of the People’s Republic, the messages have shifted to moral and normative topics, and their visualization has become much more sophisticated than in the earlier periods. This is partly because they Valjakka, Minna & Wang, Meiqin (eds.), Visual Arts, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China: Urbanized Interface.