Mcquay, Alicia (DM Harp).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

An Historical Investigation of the Recreational Philosophy, Views, Practices and Activities of Brigham Young

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1972 An Historical Investigation of the Recreational Philosophy, Views, Practices and Activities of Brigham Young David Lawrence Bolliger Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Recreational Therapy Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bolliger, David Lawrence, "An Historical Investigation of the Recreational Philosophy, Views, Practices and Activities of Brigham Young" (1972). Theses and Dissertations. 4538. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4538 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1zaz AN historical investigation OF THE recreational philosophy VIEWS PRACTICES AND activities OF BRIGHAM YOUNG A thesis presented to the department of recreation education brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degredegreee master of arts by david lawrence bolliger august 1972 this thesis by david lawrence bolliger is accepted in its present form by the department of recreation education of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree hofmasterof masterofmaster of arts s V jainjalnjaan F D shoyoehoyo s corrdmiteharananan aluaalwa heaton committee memberer 1 x4I xadadat -

Maude Adams and the Mormons

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013-1 Maude Adams and the Mormons J. Michael Hunter Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hunter, J. Michael, "Maude Adams and the Mormons" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1391. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1391 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mormons and Popular Culture The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon Volume 1 Cinema, Television, Theater, Music, and Fashion J. Michael Hunter, Editor Q PRAEGER AN IMPRI NT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC Santa Barbara, Ca li fornia • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mormons and popular culture : the global influence of an American phenomenon I J. Michael Hunter, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-39167-5 (alk. paper) - ISBN 978-0-313-39168-2 (ebook) 1. Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-Influence. 2. Mormon Church Influence. 3. Popular culture-Religious aspects-Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

May 2005 New

THE MAY 2005 SPECIAL ISSUE: THE TIMES AND SEASONS OF JOSEPH SMITH The New Era Magazine oseph Volume 35, Number 5 oseph May 2005 Smith . Official monthly publication J Jhas done for youth of The Church of Jesus Christ more, save of Latter-day Saints Jesus only, for The New Era can be found the salvation in the Gospel Library at www.lds.org. of men in this world, than Editorial Offices: any other man New Era any other man 50 E. North Temple St. that ever lived Rm. 2420 Salt Lake City, UT in it” (D&C 84150-3220, USA 135:3). E-mail address: cur-editorial-newera In this @ldschurch.org special issue, Please e-mail or send stories, articles, photos, poems, and visit the ideas to the address above. Unsolicited material is wel- places where come. For return, include a the Prophet self-addressed, stamped the Prophet envelope. Joseph Smith To Subscribe: lived, and feel By phone: Call 1-800-537- 5971 to order using Visa, the spirit of MasterCard, Discover Card, or American Express. Online: all he Go to www.ldscatalog.com. By mail: Send $8 U.S. accomplished check or money order to Distribution Services, as the first P.O. Box 26368, Salt Lake City, UT President of 84126-0368, USA. The Church of To change address: Jesus Christ of Send old and new address information to Distribution Latter-day Services at the address above. Please allow 60 days Saints. for changes to take effect. Cover: Young Joseph Smith begins the great work of the Restoration. -

The Delights of Making Cumorah's Music

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 13 Number 1 Article 8 7-31-2004 The Delights of Making Cumorah's Music Crawford Gates Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gates, Crawford (2004) "The Delights of Making Cumorah's Music," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 13 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol13/iss1/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title The Delights of Making Cumorah’s Music Author(s) Crawford Gates Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 13/1–2 (2004): 70–77. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract As a missionary in the Eastern States Mission, Crawford Gates participated in the Hill Cumorah Pageant in 1941. Although he loved the music and considered it appro- priate to the Book of Mormon scenes of the pageant, he thought then that the pageant needed its own tailor- made musical score. Twelve years later he was given the opportunity to create that score. Gates details the challenge of creating a 72-minute musical score for a full symphony orchestra and chorus while working full time as a BYU music faculty member and juggling church and family responsibilities. When that score was retired 31 years later, Gates was again appointed to create a score for the new pageant. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

The Case of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

religions Article The Role of Religious Leaders in Religious Heritage Tourism Development: The Case of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Daniel H. Olsen 1,* and Scott C. Esplin 2 1 Department of Geography, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA 2 Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 March 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020; Published: 20 May 2020 Abstract: For centuries, people have traveled to sacred sites for multiple reasons, ranging from the performance of religious rituals to curiosity. As the numbers of visitors to religious heritage sites have increased, so has the integration of religious heritage into tourism supply offerings. There is a growing research agenda focusing on the growth and management of this tourism niche market. However, little research has focused on the role that religious institutions and leadership play in the development of religious heritage tourism. The purpose of this paper is to examine the role of religious leaders and the impacts their decisions have on the development of religious heritage tourism through a consideration of three case studies related to recent decisions made by the leadership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Keywords: tourism development; religious tourism; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; Nauvoo; Illinois; Salt Lake City; Utah; Temple Square; religious pageants 1. Introduction For millennia, natural and human-built religious sites and landscapes have drawn both the faithful and the curious to travel long distances to participate in or observe religious rituals, or educational and leisure-related activities (Timothy and Olsen 2006; Suntikul and Butler 2018). -

Music Education in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 2 4-1-1962 Music Education in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Harold Laycock Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Laycock, Harold (1962) "Music Education in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Laycock: Music Education in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint music education in the church of jesus christ of latter day saints HAROLD LAYCOCK how does music fit in to the mormon way of life what is its place in latter day saint theology and philosophy in what directions can it most effectively contribute to the en- richmentrichment of our daily lives or more significantly what part should music play in helping the individual on his eternal journey toward perfection if these questions could be con- clusivelyclusively answered we would be in possession of a definitive guiding principle a measuring rod by which we could evaluate all phases of musical activity whether they pertain to public worship to the home to the school to recreational programs and amusements or to the reflective and creative thoughts -

Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R. Ricketts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ricketts, eJ remy R.. "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeremy R. Ricketts Candidate American Studies Departmelll This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Commillee: , Chairperson Alex Lubin, PhD &/I ;Se, tJ_ ,1-t C- 02-s,) Lori Beaman, PhD ii IMAGINING THE SAINTS: REPRESENTATIONS OF MORMONISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE BY JEREMY R. RICKETTS B. A., English and History, University of Memphis, 1997 M.A., University of Alabama, 2000 M.Ed., College Student Affairs, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii ©2011, Jeremy R. Ricketts iv DEDICATION To my family, in the broadest sense of the word v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making, and would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. My dissertation committee has provided invaluable guidance during my time at the University of New Mexico (UNM). -

Dancing As an Aspect of Early Mormon and Utah Culture

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 16 Issue 1 Article 12 1-1-1976 Dancing as an Aspect of Early Mormon and Utah Culture Leona Holbrook Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Holbrook, Leona (1976) "Dancing as an Aspect of Early Mormon and Utah Culture," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol16/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Holbrook: Dancing as an Aspect of Early Mormon and Utah Culture college of physical education dancing as an aspect of early mormon and utah culture leona holbrook ANALYSIS OF CULTURE when we speak of culture we think of a commendable quality upon careful analysis we will realize that there are varieties and degrees of culture it is commendable for a people to be in pos- session of a high degree of culture and probably not to their credit if they are short of this attainment not long ago I1 heard a man say 1 I m gonna take some courses and get some culture culture is not for one to get culture is growth progression a matter of becoming there will be a too brief development of the theme here that cormonsmormons had a form of culture in their dancing considering their total culture a brief re- port on their dancing is but an aspect it -

Policing the Borders of Identity At

POLICING THE BORDERS OF IDENTITY AT THE MORMON MIRACLE PAGEANT Kent R. Bean A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2005 Jack Santino, Advisor Richard C. Gebhardt, Graduate Faculty Representative John Warren Nathan Richardson William A. Wilson ii ABSTRACT Jack Santino, Advisor While Mormons were once the “black sheep” of Christianity, engaging in communal economic arrangements, polygamy, and other practices, they have, since the turn of the twentieth century, modernized, Americanized, and “Christianized.” While many of their doctrines still cause mainstream Christians to deny them entrance into the Christian fold, Mormons’ performance of Christianity marks them as not only Christian, but as perhaps the best Christians. At the annual Mormon Miracle Pageant in Manti, Utah, held to celebrate the origins of the Mormon founding, Evangelical counter- Mormons gather to distribute literature and attempt to dissuade pageant-goers from their Mormonism. The hugeness of the pageant and the smallness of the town displace Christianity as de facto center and make Mormonism the central religion. Cast to the periphery, counter-Mormons must attempt to reassert the centrality of Christianity. Counter-Mormons and Mormons also wrangle over control of terms. These “turf wars” over issues of doctrine are much more about power than doctrinal “purity”: who gets to authoritatively speak for Mormonism. Meanwhile, as Mormonism moves Christianward, this creates room for Mormon fundamentalism, as small groups of dissidents lay claim to Joseph Smith’s “original” Mormonism. Manti is home of the True and Living Church of Jesus Christ of Saints of the Last Days, a group that broke away from the Mormon Church in 1994 and considers the mainstream church apostate, offering a challenge to its dominance in this time and place. -

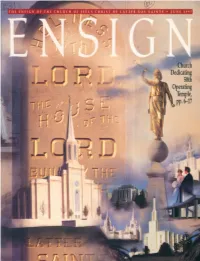

Church Dedicating 50Th Operating Temple, Pp

Church Dedicating 50th Operating Temple, pp. 6-17 THE PIONEER TREK NAUVOO TO WINTER QUARTERS BY WILLIAM G. HARTLEY Latter-day Saints did not leave Nauvoo, Illinois, tn 1846 tn one mass exodus led by President Brigham Young but primarily tn three separate groups-tn winter, spring, and fall. Beginning in February 1846, many Latter-day Saints were found crossing hills and rivers on the trek to Winter Quarters. he Latter-day Saints' epic evacuation from Nauvoo, ORIGINAL PLAN WAS FOR SPRING DEPARTURE Illinois, in 1846 may be better understood by com On 11 October 1845, Brigham Young, President and Tparing it to a three-act play. Act 1, the winter exo senior member of the Church's governing Quorum of dus, was President Brigham Young's well-known Camp Twelve Apostles, responded in behalf of the Brethren to of Israel trek across Iowa from 1 March to 13 June 1846, anti-Mormon rhetoric, arson, and assaults in September. involving perhaps 3,000 Saints. Their journey has been He appointed captains for 25 companies of 100 wagons researched thoroughly and often stands as the story of each and requested each company to build its own the Latter-day Saints' exodus from Nauvoo.1 Act 2, the wagons to roll west in one massive 2,500-wagon cara spring exodus, which history seems to have overlooked, van the next spring.2 Church leaders instructed mem showed three huge waves departing Nauvoo, involving bers outside of Illinois to come to Nauvoo in time to some 10,000 Saints, more than triple the number in the move west in the spring.