Laboratory-Acquired Infections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognizing and Treating New and Emerging Infections Encountered in Everyday Practice

Recognizing and treating new and emerging infections encountered in everyday practice STEVEN M. GORDON, MD NFECTIOUS DISEASES, pre- MiikWirj:« Although infectious diseases were once considered a dicted earlier in this cen- diminishing threat, new pathogens are constantly challenging tury to be eliminated as a the health care system. This article reviews the clinical presen- public health problem, re- tation, diagnosis, and treatment of seven emerging infections I main the chief cause of death that primary care physicians are likely to encounter. worldwide and a significant cause of death and morbidity in i Parvovirus B19 attacks erythrocyte precursors; the United States.1 Challenging infection is usually benign and self-limiting but can cause the US public health system are aplastic crises in patients with chronic hemolytic disorders. several newly identified patho- Hemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli 0157:H7 infection gens (eg, human immunodefi- can lead to the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, especially in chil- ciency virus [HIV], Escherichia dren; it also can cause thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. coli 0157:H7, hepatitis C) and a Chlamydia pneumoniae causes a mild pneumonia that resem- resurgence of old diseases pre- bles mycoplasmal pneumonia. Bacillary angiomatosis primar- sumed to be under control (eg, ily affects immunocompromised patients, especially those tuberculosis, syphilis). Further, infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At least multiple-drug resistance in two organisms can cause bacillary angiomatosis: Bartonella hense- strains of pneumococci, gono- lae and Bartonella quintana. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cocci, enterococci, staphylo- is spread by exposure to the droppings of infected rodents. cocci, salmonella, and mycobac- Contrary to previous thought, HIV continues to replicate teria undermines efforts to throughout the course of the illness and does not have a latency control the diseases they cause.2 phase. -

Know Your Abcs: a Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio

Know Your ABCs: A Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio From the Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 3701-3; Effective August 1, 2019 Class A: Diseases of major public health concern because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread – report immediately via telephone upon recognition that a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result exists. • Anthrax • Measles • Rubella (not congenital) • Viral hemorrhagic fever • Botulism, foodborne • Meningococcal disease • Severe acute respiratory (VHF), including Ebola virus • Cholera • Middle East Respiratory syndrome (SARS) disease, Lassa fever, Marburg • Diphtheria Syndrome (MERS) • Smallpox hemorrhagic fever, and • Influenza A – novel virus • Plague • Tularemia Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic infection • Rabies, human fever Any unexpected pattern of cases, suspected cases, deaths or increased incidence of any other disease of major public health concern, because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread, which may indicate a newly recognized infectious agent, outbreak, epidemic, related public health hazard or act of bioterrorism. Class B: Disease of public health concern needing timely response because of potential for epidemic spread – report by the end of the next business day after the existence of a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result is known. • Amebiasis • Carbapenemase-producing • Hepatitis B (perinatal) • Salmonellosis • Arboviral neuroinvasive and carbapenem-resistant • Hepatitis C (non-perinatal) • Shigellosis -

Communicable Diseases Weekly Report

Communicable Diseases Weekly Report Week 08, 21 February to 27 February 2021 In summary, we report: • Chancroid – one new case in a returned traveller • Rodent-borne disease risks • Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) • Summary of notifiable conditions activity in NSW For further information see NSW Health infectious diseases page. This includes links to other NSW Health infectious disease surveillance reports and a diseases data page for a range of notifiable infectious diseases. Chancroid One case of chancroid was notified this reporting week in a traveller returning from overseas. Chancroid is an acute sexually transmitted bacterial infection that causes painful genital ulcers. The condition is now rarely seen in Australia and only one other case has been notified in NSW during the past decade. Although the incidence of chancroid is decreasing globally, it is still reported in some regions within Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and South Pacific. Chancroid genital ulcer disease is a known risk factor for the transmission of HIV. The bacterium that causes chancroid, Haemophilus ducreyi, is usually transmitted through anal, oral, or vaginal sex with an infected person. After infection, one or more ulcers (sores) develop on the genitals or around the anus. Non-genital skin infections have also been reported globally, through non-sexual skin-to-skin contact with an infected person. The ulcers are usually painful, but rarely can be asymptomatic. Swelling in the groin (due to enlarged painful lymph nodes that can liquify and develop into buboes) can also occur. Other symptoms may include pain during sexual intercourse or while urinating. An infected person can spread the infection from their genital region to other parts of their body. -

Zoonotic Diseases Fact Sheet

ZOONOTIC DISEASES FACT SHEET s e ion ecie s n t n p is ms n e e s tio s g s m to a a o u t Rang s p t tme to e th n s n m c a s a ra y a re ho Di P Ge Ho T S Incub F T P Brucella (B. Infected animals Skin or mucous membrane High and protracted (extended) fever. 1-15 weeks Most commonly Antibiotic melitensis, B. (swine, cattle, goats, contact with infected Infection affects bone, heart, reported U.S. combination: abortus, B. suis, B. sheep, dogs) animals, their blood, tissue, gallbladder, kidney, spleen, and laboratory-associated streptomycina, Brucellosis* Bacteria canis ) and other body fluids causes highly disseminated lesions bacterial infection in tetracycline, and and abscess man sulfonamides Salmonella (S. Domestic (dogs, cats, Direct contact as well as Mild gastroenteritiis (diarrhea) to high 6 hours to 3 Fatality rate of 5-10% Antibiotic cholera-suis, S. monkeys, rodents, indirect consumption fever, severe headache, and spleen days combination: enteriditis, S. labor-atory rodents, (eggs, food vehicles using enlargement. May lead to focal chloramphenicol, typhymurium, S. rep-tiles [especially eggs, etc.). Human to infection in any organ or tissue of the neomycin, ampicillin Salmonellosis Bacteria typhi) turtles], chickens and human transmission also body) fish) and herd animals possible (cattle, chickens, pigs) All Shigella species Captive non-human Oral-fecal route Ranges from asymptomatic carrier to Varies by Highly infective. Low Intravenous fluids primates severe bacillary dysentery with high species. 16 number of organisms and electrolytes, fevers, weakness, severe abdominal hours to 7 capable of causing Antibiotics: ampicillin, cramps, prostration, edema of the days. -

Enteric Infections Due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella*

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58 (4): 519-537 (1980) Enteric infections due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella* WHO SCIENTIFIC WORKING GROUP1 This report reviews the available information on the clinical features, pathogenesis, bacteriology, and epidemiology ofCampylobacter jejuni and Yersinia enterocolitica, both of which have recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection. In the fields of salmonellosis and shigellosis, important new epidemiological and relatedfindings that have implications for the control of these infections are described. Priority research activities in each ofthese areas are outlined. Of the organisms discussed in this article, Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia entero- colitica have only recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection, and accordingly the available knowledge on these pathogens is reviewed in full. In the better- known fields of salmonellosis (including typhoid fever) and shigellosis, the review is limited to new and important information that has implications for their control.! REVIEW OF RECENT KNOWLEDGE Campylobacterjejuni In the last few years, C.jejuni (previously called 'related vibrios') has emerged as an important cause of acute diarrhoeal disease. Although this organism was suspected of being a cause ofacute enteritis in man as early as 1954, it was not until 1972, in Belgium, that it was first shown to be a relatively common cause of diarrhoea. Since then, workers in Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States of America have reported its isolation from 5-14% of diarrhoea cases and less than 1 % of asymptomatic persons. Most of the information given below is based on conclusions drawn from these studies in developed countries. -

2017 Summary

KENT COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENT EPI FOCUS 2017 Communicable Disease Summary Contents Introduction What are reportable diseases? ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Michigan Disease Surveillance System (MDSS) ........................................................................................................................... 2 Gastrointestinal illnesses Campylobacter ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Shigellosis ....................................................................................................................................................................................5 Giardiasis .....................................................................................................................................................................................5 Salmonellosis .............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sexually Transmitted Infections HIV/AIDS .................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chlamydia ................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Healthy Brookline Volume

HEALTHY BROOKLINE VOLUME XVI Communicable Diseases in Brookline Brookline Department of Public Health 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Janelle Mellor, MPH, with support from Natalie Miller, MPH, Barbara Westley, RN, and Lynne Karsten, MPH, under the direction of Alan Balsam, PhD, MPH, Director of Public Health and Human Services in Brookline. Thanks are also due to the Division Directors at the Brookline Department of Public Health for their support and input: Lynne Karsten, MPH Patrick Maloney, MPAH Mary Minott, LICSW Patricia Norling Gloria Rudisch, MD, MPH Dawn Sibor, MEd Barbara Westley, RN A special thanks to the Brookline Advisory Council on Public Health Bruce Cohen, PhD-Chair Roberta Gianfortoni, MA Milly Krakow, PhD Cheryl Lefman, MA Patricia Maher, RN/NP, MA/MA Anthony Schlaff, MD, MPH Support and data were also provided by: Susan Soliva, MPH, Massachusetts Department of Public Health The Healthy Brookline Chartbooks represent a partnership with a variety of funding sources: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Brigham & Women’s Hospital Children’s Hospital Farnsworth Trust Tufts Medical Center St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Brookline Community Foundation Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation Tufts Health Plan We thank them all for their generous support. Table of Contents Section 1: Communicable Disease Surveillance and Reporting .................................................................. 1 Surveillance and Reporting ...................................................................................................................... -

Nantucket Infectious Disease Report Jan 2009- Dec 2018

Nantucket Infectious Disease Report Jan 2009- Dec 2018 Nantucket Health Department Acknowledgments Lead Author, Grace McNeil Nantucket Health Department Roberto Santamaria Health Director Hank Ross Artell Crowley Kathy LaFarve Health Inspector Assistant Health Director Health Inspector Anne Barrett Administrative Specialist Intern Staff Grace McNeil Skye Flegg Syracuse University Nantucket High School Facilitating Partners Massachusetts Department of Public Health Nantucket Infectious Disease Report 2009-2018 | Page 2 Table of Contents Infectious Disease…………………………………………………………....……………………5 Nantucket Top Five…………………………………………………....…………………..5 Lyme Disease………………………………………………………………....…………………...6 By Year of Onset………………………………………………………….……………….6 By Month of Onset……………………………………………………...…………………7 By Age Group……………………………………………………………………………..7 Babesiosis…………....……………………………………………………....……………………8 By Year of Onset………………………………………………………….……………….8 By Month of Onset……………………………………………………...…………………9 By Age Group……………………………………………………………………………..9 Hepatitis C…………………….…………………………………………………...……………..10 By Year of Onset………………………………………………………….……………...10 By Month of Onset……………………………………………………...………………..11 By Age Group……………………………………………………………………………11 Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis……………………………………………………………..12 By Year of Onset………………………………………………………….……………..12 By Month of Onset……………………………………………………...………………..13 By Age Group……………………………………………………………………………13 Influenza…………………………………………………………………………………………14 By Year of Onset………………………………………………………….……………...14 By Month of Onset……………………………………………………...………………..15 -

Individual Year Summary of Reported Cases for 2013

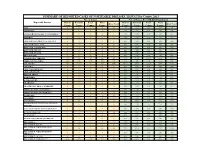

SUMMARY OF REPORTED CASES OF NOTIFIABLE DISEASES, HAWAI`I by County, 2013 No. of Cases No. of Cases Per 100,000 Population Reportable Diseases Hawaii Honolulu Kauai Maui Hawaii Honolulu Kauai Maui State Total State Total County County County County County County County County AIDS* 9 46 1 9 66 4.70 4.67 1.44 5.59 4.69 AMEBIASIS * 2 1 0 1 4 1.04 0.10 0.00 0.62 0.28 ANGIOSTRONGYLIASIS, CANTONENSIS*^ 3 0 0 0 3 1.57 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.21 ANTHRAX 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ARBOVIRUSES, GROUP A & GROUP B 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ARENAVIRUSES, LASSA 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BOTULISM, INFANT 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BOTULISM, WOUND 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BRUCELLOSIS 1 0 0 0 1 0.52 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.07 CAMPYLOBACTERIOSIS 142 521 70 88 825 74.12 52.85 100.54 54.63 58.59 CHIKUNGUNYA VIRUS N/R N/R N/R N/R N/R N/A N/R N/R N/R N/R CHLAMYDIA 768 5185 161 523 6640 400.87 526.00 231.24 324.65 471.58 CHOLERA 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS 0 1 0 0 1 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.07 CYCLOSPORIASIS 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 DENGUE FEVER 1 6 0 3 10 0.52 0.61 0.00 1.86 0.71 DIPHTHERIA 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 E. -

Reportable Diseases by County - 2015 Page 1

Connecticut Department of Public Health Reported Cases of Connecticut Reportable Diseases by County - 2015 Page 1 DISEASE Fairfield Hartford Litchfield Middlesex New Haven New London Tolland Windham Unknown Total Acute flaccid myelitis 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Anthrax 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Babesiosis 36 17 19 25 24 94 14 57 0 286 Botulism (includes infant) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Brucellosis 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 California group arbovirus infection 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Campylobacter 245 153 44 36 172 45 22 17 0 734 Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae ** 29 16 9 3 57 4 6 1 1 126 Chikungunya 6 4 1 0 4 0 0 1 0 16 Cholera 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cryptosporidiosis 34 16 5 2 15 2 4 3 0 81 Cyclospora infection 7 4 1 2 2 0 0 0 0 16 Dengue Fever (confirmed & probable) 2 3 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 6 Diphtheria 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Eastern Equine Encephalitis (human) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Escherichia coli O157:H7 gastroenteritis 11 6 1 0 7 0 0 2 0 27 Escherichia coli non-O157, Shiga-toxin producing 38 10 4 1 13 3 9 1 0 79 Giardiasis 68 31 16 13 58 16 5 6 2 215 Group A streptococcal disease, invasive 43 56 19 12 64 15 14 13 0 236 Group B streptococcal disease, invasive 77 144 33 22 124 28 9 13 0 450 H. -

Oklahomastatedepartme Ntofh

2011 ANNUAL SUMMARY OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES · OKLAHOMA STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 2011 ANNUAL SUMMARY OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES · OKLAHOMA STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Executive Summary 2011 Annual Summary of Infectious Diseases The Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH) is pleased to send you a copy of the 2011 Annual Summary of Infectious Diseases. The information contained in this report consolidates summaries of communicable disease surveillance and investigations conducted by the OSDH during 2011. Communicable disease summaries were written by personnel in the OSDH Acute Disease Service, HIV/STD Service, and the Public Health Laboratory. Specifically, the annual summary contains information on the numbers and incidence rates of reportable infectious diseases at the state and county level, disease specific data collected during public health investigations, and summaries of program activities. Title 63 Oklahoma Statute §1-503 as well as Oklahoma Administrative Code (OAC) Title 310, Chapter 515 require that healthcare providers and laboratories report cases of certain communicable diseases to the OSDH. This allows the surveillance, investigation, and control of the spread of disease in the population by public health personnel. A list of the Oklahoma notifiable disease rules is included in this annual summary for your reference. The diseases listed in the Oklahoma disease reporting rules must be reported, along with patient identifiers, demographics, and contact information, to the OSDH upon discovery as dictated in sections OAC 310:515-1-3 and OAC 310:515-1-4. The current “Oklahoma Disease Reporting Manual” is the standard reference for disease-specific diagnostic test results to be reported. The current edition of the "Oklahoma Disease Reporting Manual" and additional disease reporting resources may be accessed from the Acute Disease Service disease reporting web page of the OSDH web site at http://IDReportingAndAlerts.health.ok.gov. -

Descriptive Epidemiology of Reportable Diseases

DESCRIPTIVE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF REPORTABLE DISEASES ________________________________________________2004 Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) See Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Amebiasis Amebiasis is a parasitic infection transmitted by food or water contaminated by fecal matter containing Entameoba histolytica. Infection with amebic cysts can be asymptomatic. When infection causes disease, symptoms may include severe diarrhea, chills, or mild to moderate abdominal cramps, coupled with periods of remission. Occasionally, bloody diarrhea and fever may occur. Invasive amebiasis is most often found in young adults and is very rare in children under two years of age. There were 25 cases of amebiasis reported in Virginia in 2004. Although this is a 5% decrease from the five year average of 26.2 cases per year, it marks the third year in a row of increasing numbers of cases (Figure 1). Figure 1. Amebiasis: Ten Year Trend, Virginia, 1995-2004 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 Number of Cases 5 0 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Year 5 Year Average Reference Level (1999-2003) Twenty-three cases (92%) were reported in persons 20 years or older. The 30-39 year age group had the highest incidence rate with 0.6 per 100,000. No cases occurred in infants. Forty percent of cases had no race reported. Among cases with a reported race, the black population had the highest infection rate (0.5 per 100,000). Most cases (16) occurred in the northern region, which had an incidence rate of 0.8 per 100,000. This was followed by the northwest region (5 cases, 0.4 per 100,000).