Epidemiology of Milk-Borne Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Tick-Borne Diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2*

Wu et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:119 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/119 REVIEW Open Access Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2* Abstract As an important contributor to vector-borne diseases in China, in recent years, tick-borne diseases have attracted much attention because of their increasing incidence and consequent significant harm to livestock and human health. The most commonly observed human tick-borne diseases in China include Lyme borreliosis (known as Lyme disease in China), tick-borne encephalitis (known as Forest encephalitis in China), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (known as Xinjiang hemorrhagic fever in China), Q-fever, tularemia and North-Asia tick-borne spotted fever. In recent years, some emerging tick-borne diseases, such as human monocytic ehrlichiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and a novel bunyavirus infection, have been reported frequently in China. Other tick-borne diseases that are not as frequently reported in China include Colorado fever, oriental spotted fever and piroplasmosis. Detailed information regarding the history, characteristics, and current epidemic status of these human tick-borne diseases in China will be reviewed in this paper. It is clear that greater efforts in government management and research are required for the prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of tick-borne diseases, as well as for the control of ticks, in order to decrease the tick-borne disease burden in China. Keywords: Ticks, Tick-borne diseases, Epidemic, China Review (Table 1) [2,4]. Continuous reports of emerging tick-borne Ticks can carry and transmit viruses, bacteria, rickettsia, disease cases in Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and spirochetes, protozoans, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma,Bartonia other provinces demonstrate the rise of these diseases bodies, and nematodes [1,2]. -

Recognizing and Treating New and Emerging Infections Encountered in Everyday Practice

Recognizing and treating new and emerging infections encountered in everyday practice STEVEN M. GORDON, MD NFECTIOUS DISEASES, pre- MiikWirj:« Although infectious diseases were once considered a dicted earlier in this cen- diminishing threat, new pathogens are constantly challenging tury to be eliminated as a the health care system. This article reviews the clinical presen- public health problem, re- tation, diagnosis, and treatment of seven emerging infections I main the chief cause of death that primary care physicians are likely to encounter. worldwide and a significant cause of death and morbidity in i Parvovirus B19 attacks erythrocyte precursors; the United States.1 Challenging infection is usually benign and self-limiting but can cause the US public health system are aplastic crises in patients with chronic hemolytic disorders. several newly identified patho- Hemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli 0157:H7 infection gens (eg, human immunodefi- can lead to the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, especially in chil- ciency virus [HIV], Escherichia dren; it also can cause thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. coli 0157:H7, hepatitis C) and a Chlamydia pneumoniae causes a mild pneumonia that resem- resurgence of old diseases pre- bles mycoplasmal pneumonia. Bacillary angiomatosis primar- sumed to be under control (eg, ily affects immunocompromised patients, especially those tuberculosis, syphilis). Further, infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At least multiple-drug resistance in two organisms can cause bacillary angiomatosis: Bartonella hense- strains of pneumococci, gono- lae and Bartonella quintana. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cocci, enterococci, staphylo- is spread by exposure to the droppings of infected rodents. cocci, salmonella, and mycobac- Contrary to previous thought, HIV continues to replicate teria undermines efforts to throughout the course of the illness and does not have a latency control the diseases they cause.2 phase. -

Fournier's Gangrene Caused by Listeria Monocytogenes As

CASE REPORT Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the primary organism Sayaka Asahata MD1, Yuji Hirai MD PhD1, Yusuke Ainoda MD PhD1, Takahiro Fujita MD1, Yumiko Okada DVM PhD2, Ken Kikuchi MD PhD1 S Asahata, Y Hirai, Y Ainoda, T Fujita, Y Okada, K Kikuchi. Une gangrène de Fournier causée par le Listeria Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the monocytogenes comme organisme primaire primary organism. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(1):44-46. Un homme de 70 ans ayant des antécédents de cancer de la langue s’est présenté avec une gangrène de Fournier causée par un Listeria A 70-year-old man with a history of tongue cancer presented with monocytogenes de sérotype 4b. Le débridement chirurgical a révélé un Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. adénocarcinome rectal non diagnostiqué. Le patient n’avait pas Surgical debridement revealed undiagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma. d’antécédents alimentaires ou de voyage apparents, mais a déclaré The patient did not have an apparent dietary or travel history but consommer des sashimis (poisson cru) tous les jours. reported daily consumption of sashimi (raw fish). L’âge avancé et l’immunodéficience causée par l’adénocarcinome rec- Old age and immunodeficiency due to rectal adenocarcinoma may tal ont peut-être favorisé l’invasion directe du L monocytogenes par la have supported the direct invasion of L monocytogenes from the tumeur. Il s’agit du premier cas déclaré de gangrène de Fournier tumour. The present article describes the first reported case of attribuable au L monocytogenes. Les auteurs proposent d’inclure la con- Fournier’s gangrene caused by L monocytogenes. -

Q Fever in Small Ruminants and Its Public Health Importance

Journal of Dairy & Veterinary Sciences ISSN: 2573-2196 Review Article Dairy and Vet Sci J Volume 9 Issue 1 - January 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Tolera Tagesu Tucho DOI: 10.19080/JDVS.2019.09.555752 Q Fever in Small Ruminants and its Public Health Importance Tolera Tagesu* School of Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, Ethiopia Submission: December 01, 2018; Published: January 11, 2019 *Corresponding author: Tolera Tagesu Tucho, School of Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, Jimma Oromia, Ethiopia Abstract Query fever is caused by Coxiella burnetii, it’s a worldwide zoonotic infectious disease where domestic small ruminants are the main reservoirs for human infections. Coxiella burnetii, is a Gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium, adapted to thrive within the phagolysosome of the phagocyte. Humans become infected primarily by inhaling aerosols that are contaminated with C. burnetii. Ingestion (particularly drinking raw milk) and person-to-person transmission are minor routes. Animals shed the bacterium in urine and feces, and in very high concentrations in birth by-products. The bacterium persists in the environment in a resistant spore-like form which may become airborne and transported long distances by the wind. It is considered primarily as occupational disease of workers in close contact with farm animals or processing their be commenced immediately whenever Q fever is suspected. To prevent both the introduction and spread of Q fever infection, preventive measures shouldproducts, be however,implemented it may including occur also immunization in persons without with currently direct contact. available Doxycycline vaccines drugof domestic is the first small line ruminant of treatment animals for Q and fever. -

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

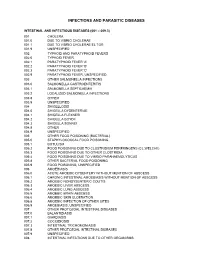

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

Coxiella Burnetii

SENTINEL LEVEL CLINICAL LABORATORY GUIDELINES FOR SUSPECTED AGENTS OF BIOTERRORISM AND EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES Coxiella burnetii American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Revised March 2016 For latest revision, see web site below: https://www.asm.org/Articles/Policy/Laboratory-Response-Network-LRN-Sentinel-Level-C ASM Subject Matter Expert: David Welch, Ph.D. Medical Microbiology Consulting Dallas, TX [email protected] ASM Sentinel Laboratory Protocol Working Group APHL Advisory Committee Vickie Baselski, Ph.D. Barbara Robinson-Dunn, Ph.D. Patricia Blevins, MPH University of Tennessee at Department of Clinical San Antonio Metro Health Memphis Pathology District Laboratory Memphis, TN Beaumont Health System [email protected] [email protected] Royal Oak, MI BRobinson- Erin Bowles David Craft, Ph.D. [email protected] Wisconsin State Laboratory of Penn State Milton S. Hershey Hygiene Medical Center Michael A. Saubolle, Ph.D. [email protected] Hershey, PA Banner Health System [email protected] Phoenix, AZ Christopher Chadwick, MS [email protected] Association of Public Health Peter H. Gilligan, Ph.D. m Laboratories University of North Carolina [email protected] Hospitals/ Susan L. Shiflett Clinical Microbiology and Michigan Department of Mary DeMartino, BS, Immunology Labs Community Health MT(ASCP)SM Chapel Hill, NC Lansing, MI State Hygienic Laboratory at the [email protected] [email protected] University of Iowa [email protected] Larry Gray, Ph.D. Alice Weissfeld, Ph.D. TriHealth Laboratories and Microbiology Specialists Inc. Harvey Holmes, PhD University of Cincinnati College Houston, TX Centers for Disease Control and of Medicine [email protected] Prevention Cincinnati, OH om [email protected] [email protected] David Welch, Ph.D. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Know Your Abcs: a Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio

Know Your ABCs: A Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio From the Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 3701-3; Effective August 1, 2019 Class A: Diseases of major public health concern because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread – report immediately via telephone upon recognition that a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result exists. • Anthrax • Measles • Rubella (not congenital) • Viral hemorrhagic fever • Botulism, foodborne • Meningococcal disease • Severe acute respiratory (VHF), including Ebola virus • Cholera • Middle East Respiratory syndrome (SARS) disease, Lassa fever, Marburg • Diphtheria Syndrome (MERS) • Smallpox hemorrhagic fever, and • Influenza A – novel virus • Plague • Tularemia Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic infection • Rabies, human fever Any unexpected pattern of cases, suspected cases, deaths or increased incidence of any other disease of major public health concern, because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread, which may indicate a newly recognized infectious agent, outbreak, epidemic, related public health hazard or act of bioterrorism. Class B: Disease of public health concern needing timely response because of potential for epidemic spread – report by the end of the next business day after the existence of a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result is known. • Amebiasis • Carbapenemase-producing • Hepatitis B (perinatal) • Salmonellosis • Arboviral neuroinvasive and carbapenem-resistant • Hepatitis C (non-perinatal) • Shigellosis -

Communicable Diseases Weekly Report

Communicable Diseases Weekly Report Week 08, 21 February to 27 February 2021 In summary, we report: • Chancroid – one new case in a returned traveller • Rodent-borne disease risks • Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) • Summary of notifiable conditions activity in NSW For further information see NSW Health infectious diseases page. This includes links to other NSW Health infectious disease surveillance reports and a diseases data page for a range of notifiable infectious diseases. Chancroid One case of chancroid was notified this reporting week in a traveller returning from overseas. Chancroid is an acute sexually transmitted bacterial infection that causes painful genital ulcers. The condition is now rarely seen in Australia and only one other case has been notified in NSW during the past decade. Although the incidence of chancroid is decreasing globally, it is still reported in some regions within Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and South Pacific. Chancroid genital ulcer disease is a known risk factor for the transmission of HIV. The bacterium that causes chancroid, Haemophilus ducreyi, is usually transmitted through anal, oral, or vaginal sex with an infected person. After infection, one or more ulcers (sores) develop on the genitals or around the anus. Non-genital skin infections have also been reported globally, through non-sexual skin-to-skin contact with an infected person. The ulcers are usually painful, but rarely can be asymptomatic. Swelling in the groin (due to enlarged painful lymph nodes that can liquify and develop into buboes) can also occur. Other symptoms may include pain during sexual intercourse or while urinating. An infected person can spread the infection from their genital region to other parts of their body. -

Zoonotic Diseases Fact Sheet

ZOONOTIC DISEASES FACT SHEET s e ion ecie s n t n p is ms n e e s tio s g s m to a a o u t Rang s p t tme to e th n s n m c a s a ra y a re ho Di P Ge Ho T S Incub F T P Brucella (B. Infected animals Skin or mucous membrane High and protracted (extended) fever. 1-15 weeks Most commonly Antibiotic melitensis, B. (swine, cattle, goats, contact with infected Infection affects bone, heart, reported U.S. combination: abortus, B. suis, B. sheep, dogs) animals, their blood, tissue, gallbladder, kidney, spleen, and laboratory-associated streptomycina, Brucellosis* Bacteria canis ) and other body fluids causes highly disseminated lesions bacterial infection in tetracycline, and and abscess man sulfonamides Salmonella (S. Domestic (dogs, cats, Direct contact as well as Mild gastroenteritiis (diarrhea) to high 6 hours to 3 Fatality rate of 5-10% Antibiotic cholera-suis, S. monkeys, rodents, indirect consumption fever, severe headache, and spleen days combination: enteriditis, S. labor-atory rodents, (eggs, food vehicles using enlargement. May lead to focal chloramphenicol, typhymurium, S. rep-tiles [especially eggs, etc.). Human to infection in any organ or tissue of the neomycin, ampicillin Salmonellosis Bacteria typhi) turtles], chickens and human transmission also body) fish) and herd animals possible (cattle, chickens, pigs) All Shigella species Captive non-human Oral-fecal route Ranges from asymptomatic carrier to Varies by Highly infective. Low Intravenous fluids primates severe bacillary dysentery with high species. 16 number of organisms and electrolytes, fevers, weakness, severe abdominal hours to 7 capable of causing Antibiotics: ampicillin, cramps, prostration, edema of the days. -

Establishment of Listeria Monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract

microorganisms Review Establishment of Listeria monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract Morgan L. Davis 1, Steven C. Ricke 1 and Janet R. Donaldson 2,* 1 Center for Food Safety, Department of Food Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72704, USA; [email protected] (M.L.D.); [email protected] (S.C.R.) 2 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-601-266-6795 Received: 5 February 2019; Accepted: 5 March 2019; Published: 10 March 2019 Abstract: Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram positive foodborne pathogen that can colonize the gastrointestinal tract of a number of hosts, including humans. These environments contain numerous stressors such as bile, low oxygen and acidic pH, which may impact the level of colonization and persistence of this organism within the GI tract. The ability of L. monocytogenes to establish infections and colonize the gastrointestinal tract is directly related to its ability to overcome these stressors, which is mediated by the efficient expression of several stress response mechanisms during its passage. This review will focus upon how and when this occurs and how this impacts the outcome of foodborne disease. Keywords: bile; Listeria; oxygen availability; pathogenic potential; gastrointestinal tract 1. Introduction Foodborne pathogens account for nearly 6.5 to 33 million illnesses and 9000 deaths each year in the United States [1]. There are over 40 pathogens that can cause foodborne disease. The six most common foodborne pathogens are Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium perfringens. -

Bartonella Henselae and Coxiella Burnetii Infection and the Kawasaki Disease

GALLEY PROOF J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Mgt. 2004 JASEM ISSN 1119-8362 Available Online at All rights reserved http:// www.bioline.org.br/ja Vol. 8 (1) 11 - 12 Bartonella henselae and Coxiella burnetii Infection and the Kawasaki Disease KEI NUMAZAKI, M D Department of Pediatrics, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, S.1 W.16 Chuo-ku Sapporo, 060-8543 Japan Phone: +81-611-2111 X3413 Fax: +81-611-0352 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: It was reported that Bartonella henselae, B. quintana and Coxiella burnetii was not strongly associated with coronary artery disease but on the basis of geometric mean titer, C. burnetii infection might have a modest association with coronary artery disease. Serum antibodies to B. henselae from 14 patients with acute phase of Kawasaki disease were determined by the indirect fluorescence antibody assay . Serum antibodies to C. burnetii were also tried to detect. However, no positive results were obtained. I also examined 10 children and 10 pregnant women who had serum IgG antibody to B. henselae or to C. burnetii. No one showed abnormal findings of coronary artery. @JASEM Several Bartonella species cause illness and associated with several infections, including asymptotic infection in humans. B. henselae has Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, been associated with an increasing spectrum of Helicobacter pylori and other intercellular bacteria clinical syndromes including cat scratch disease. (Danesh et al., 1997). Previous studies supported Although the clinical spectrum has not been the possibility of certain populations having an completely clarified, B. quintana may cause association of infections and coronary artery disease blood-culture negative endocarditis in children Kawasaki disease (KD).