From Terror to Communion in Whitley Strieber’S Communion (1987)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformation the Breakthrough Whitley Strieber

TRANSFORMATION THE BREAKTHROUGH WHITLEY STRIEBER On February 10, 1987, one of the most star tling and controversial books of our time was published: Whitley Strieber's Commu nion. In Communion, Whitley Strieber de scribed the shattering effects of an assault from the unknown-what seemed to be an encounter with intelligent nonhuman beings. Transformation is the chronicle of his effort to form a relationship with the unknown reality he has come to call"the visitors." After writing Communion, Whitley Strie ber firmly expected that his encounters with the "visitors" would end. They did not. At first he was desperate and terrified. He struggled frantically to push the visitors out of his life, to prove to himself that they were figments of his imagination, that they were anything but a reality separate from himself. He was finally forced to admit, because of their persistence and the undeniably intelli gent structure of their encounters with him, that they had to be a genuine mystery, an intelligence of unknown nature and origin. Whitley began to challenge his fear of the visitors, to try to confront them with objec tivity, in an effort to gain real insight into their impact on our lives. The more he did this, he found, the deeper and richer his ex perience became. Do the visitors represent a force that has been with mankind throughout history? Has it played an absolutely central role in alter ing human culture? Has a conscious force (continued on backflap) Book Club Edition TRANSFORMATI ON By Whitley Strieber As Author: Transformation Communion Wo lfof Shadows Catmagic Th e Night Church Black Magic The Hunger The Wolfen As Co-Author: Nature's End Wa rday Whitley Strieber TRANSFORMATION The Breakthrough BEECH TREE BOOKS WILLIAM MOR ROW New York Copyright C 1988 by Wilson & Neff, Inc. -

Problems with Strieber and the Key

PERISTALSIS: A DIGEST Vol. 143, No. 2, March 2017 Problems with Strieber and The Key HEINRICH MOLTKE THE EMPTY MAN A MÔMO IMPRINT ABSTRACT THE KEY by Whitley Strieber presents a conversation Strieber claims to have had with an otherworldly visitor offering a “new vision” of God and man along with previously unknown scientific knowledge and pre- dictions for the future. This article critically examines The Key and uses textual evidence from Strieber’s previous books, articles, and interviews to show that ideas purportedly originating with the visitor appear throughout Strieber’s previous work. This article notes that scientific assertions made in The Key, far from being new and unknown, draw on the popular scientific literature at around the time Strieber wrote The Key. This article also examines the controversy surrounding differences between The Key’s two published versions, suggesting that contrary to Strieber’s improbable claim that his 2001 text had been altered by “sin- ister forces” without his knowledge, Strieber authored the text of both editions. Strieber’s inability to notice the similarity between his own public statements and the “breathtakingly new” ideas presented by his visitor combined with his unsupportable charge of censorship against his own self-published book call into question his credibility as a bridge between intellectual culture and the experience of the otherworldly. ] Page numbers in parentheses ( ) refer to the 2001 Walker & Collier edition of The Key unless otherwise noted. Numbers in superscript with brackets [ ] link to end notes. Quotations from digital texts are sic erat scriptum. • © 2017 The Empty Man Ltd • VERSION 1.05 PERISTALSIS: A DIGEST VOL. -

The Strengthening Aspects of Zen and Contemporary Meditation Practices

The Strengthening Aspects of Zen and Contemporary Meditation Practices By Kathleen O’Shaughnessy Excerpts from Chapter 19 of: Spiritual Growth with Entheogens – Psychoactive Sacramentals and Human Transformation Edited by Thomas B. Roberts ©2001, 2012 by the Council on Spiritual Practices Kathleen O’Shaughnessy has a thirty-year background in Soto Zen practice, psychosynthesis and gestalt therapy, movement as a means of expanding the capabilities of the human nervous system, the fragilities of nutritional healing, primary shamanic states (including plant-induced frames of mind), multiple and multilevel bodywork approaches to balance, and the practicalities of transpersonal crisis. Meditation: Reflecting on Your Attitude toward Altered States What is your relationship to unusual and altered states in meditation? As you read about these experiences, notice which ones touch you, notice where you are attracted or what reminds you of past experiences. How do you meet such experiences when they arise? Are you attached and proud of them? Do you keep trying to repeat them as a mark of your progress or success? Have you gotten stuck trying to make them return over and over again? How much wisdom have you brought to them? Are they a source of entanglement or a source of freedom for you? Do you sense them as beneficial and healing, or are they frightening? Just as you can misuse these states through attachment, you can also misuse them by avoiding them and trying to stop them. If this is the case, how could your meditation deepen if you opened to them? Let yourself sense the gifts they can bring, gifts of inspiration, new perspectives, insight, healing, or extraordinary faith. -

Psychedelic Research Revisited

PSYCHEDELIC RESEARCH REVISITED James Fadiman Ph.D. Menlo Park, CA Charles Grob MD Torrance, CA Gary Bravo MD Santa Rosa, CA Alise Agar (deceased) Roger Walsh MD, Ph.D. Irvine, CA ABSTRACT: In the two decades before the government banned human subjects studies in the mid 1960s, an enormous amount of research was done on psychedelics. These studies hold far reaching implications for our understanding of diverse psychological, social, and religious phenomena. With further research all but legally impossible, this makes the original researchers a unique and invaluable resource, and so they were interviewed to obtain their insights and reflections. One of these researchers was James Fadiman, who subsequently became a cofounder of the Association for Transpersonal Psychology and the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. Discussion topics include his research studies and personal experiences, the founding, nature and purpose of transpersonal psychology, social effects of, and responses to, psychedelics, and religious freedom. INTRODUCTION For half a century psychedelics have rumbled through the Western world, seeding a subculture, titillating the media, fascinating youth, terrifying parents, enraging politicians, and intriguing researchers. Tens of millions of people have used them; millions still do—sometimes carefully and religiously, often casually and danger- ously. They have been a part—often a central and sacred part—of many societies throughout history. In fact, until recently the West was a curious anomaly in not recognizing psychedelics as spiritual and medical resources (Grob, 1998, 2002; Harner, 1973). The discovery of LSD in 1943 (Hoffman, 1983), and later its chemical cousins—such as mescaline, psilocybin and MDMA—unleashed experiences of such intensity and This paper is excerpted from a more extensive interview which will be published in a book tentatively entitled Higher Wisdom. -

Fall 2015 Hay House

FALL 2015 HAY HOUSE This edition of the catalogue was printed on May 5, 2015. To view updates, please see the Fall 2015 Raincoast eCatalogue or visit www.raincoast.com Hay House | Fall 2015 Catalogue Uplifting Prayers to Light Your Way 200 Invocations for Challenging Times Sonia Choquette _____________________________________________________________________ In this gift-sized book, Sonia Choquette shares uplifting prayers and heartfelt invocations to help you stay connected to your intuitive spirit so that you may receive support from your ever- present, loving Divine Creator and all your unseen spiritual helpers who are here to guide you through difficult times. Presented in the format of a prayer per page, each beautifully written, intimate prayer is straight to the point and speaks to the messiness and hard work of transformation. They will give you the strength and good humor to keep flowing with life and enable you to face whatever the universe may put in your path with courage, confidence, and creativity. They will also guide you to the support you need to forgive your hurts, resentments, and injuries, allowing you to be more fully available to the beautiful, Hay House new life unfolding before you. Whether read in one sitting, or On Sale: Sep 1/15 used again and again, this is a book that will bring a deep sense 5 x 7 of peace and renewed optimism. _____________________________________________________________________ 9781401944537 • $19.99 • cl Author Bio Body, Mind & Spirit / Healing / Prayer & Spiritual 15F Hay House: p. 1 Sonia Choquette, a world-renowned intuitive guide and spiritual teacher, is the author of 19 international best-selling books, including the New York Times bestseller The Answer Is Simple . -

The Coming Global Superstorm

The Coming Global Superstorm The Coming Global Superstorm. Simon and Schuster, 2001. Art Bell, Whitley Strieber. 0743417410, 9780743417419. 272 pages. 2001 Killer tornadoes. Violent tropical storms. Devastating temperatures. Are these just the prelude to an unprecedented environmental disaster in our near future? Two of America's leading investigators of unexplained phenomena -- Art Bell, the top-rated late-night radio talk-show host, and Whitley Strieber, No. 1 New York Times bestselling author of Communion and the legendary Nature's End -- have made a shocking discovery based on years of research with top scientists and archaeologists from around the world. Now, they reveal what powerful interests are trying to keep hidden: rapid changes in the atmosphere caused by greenhouse gases have set humanity on an incredibly dangerous course toward a catastrophic change in climate in the immediate future. It will begin with a massive, unprecedented storm that will devastate the Northern Hemisphere. This will be followed by floods unlike anything ever seen before -- or perhaps a new Ice Age. They also unearth evidence that this has happened in the past -- in fact, that it has occurred regularly throughout geologic history, but so infrequently that our only record of the last such storm is contained in ancient myths and flood legends. From El Niño to the African droughts, to the shrinking of the polar ice caps, Bell and Strieber identify the warning signs to those willing to see. They point out that the Earth's regulatory system is like a rubber band: you can stretch it just so far before it snaps back -- with a vengeance. -

Esalen and the Rise of Spiritual Privilege, by Marion Goldman. New York University Press, 2012. Xii + 207Pp., 13 B&W Illustra- Tions

International Journal for the Study of New Religions 5.1 (2014) 117–119 ISSN 2041-9511 (print) ISSN 2041-952X (online) doi:10.1558/ijsnr.v5i1.117 The American Soul Rush: Esalen and the Rise of Spiritual Privilege, by Marion Goldman. New York University Press, 2012. xii + 207pp., 13 b&w illustra- tions. $30.00, ISBN-113: 9780814732878. Reviewed by Anna Pokazanyeva, University of California, Santa Barbara, [email protected] Keywords Esalen, alternative spirituality, gender, spiritual privilege Marion Goldman’s socio-historical study of the Esalen Institute weaves together volumes of material drawn from interviews, ethnographic field work, archival work, legal records, and various primary source publications to construct a vision of the organization as a locus of development for the late twentieth-century social phenomenon of “spiritual privilege.” Gold- man defines spiritual privilege as “an individual’s ability to devote time and resources to select, combine, and revise his or her personal religious beliefs and practices over the course of a lifetime” (2). The present work broadly argues that Esalen “transformed spiritual privilege into a human right that could be available to any American dedicated to maximizing her or his poten- tial in mind, body, spirit, and emotion” (2–3). This, at least, was the Institute’s official platform—a universalization of access to spiritual exploration that rested on the metaphysical assumption that every individual was endowed with a “spark of divinity.” Goldman also explores Esalen’s contributions to the human potential movement in humanistic psychology, progressive politi- cal groups that connected social and personal issues, and the men’s movement as ways that the organization broadened the effects of spiritual privilege on popular audiences. -

Phenomenological Mapping and Comparisons of Shamanic, Buddhist, Yogic, and Schizophrenic Experiences Roger Walsh

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Phenomenological mapping and comparison of shamanic, Buddhist, yogic and schizophrenic experiences Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/34q7g39r Journal Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 61 Author Walsh, RN Publication Date 1993 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California journal of the American Academy of Religion. LXI/4 Phenomenological Mapping and Comparisons of Shamanic, Buddhist, Yogic, and Schizophrenic Experiences Roger Walsh In recent years there has been increased interest, in anthropology, psychology, religious studies, and the culture at large, in the study of alternate or altered states of consciousness (ASC). There is significant evidence that altered states may represent a core experiential component of religious and mystical traditions and that practices such as meditation and yoga may induce specific classes of ASC (Shapiro; Shapiro and Walsh; Goleman). The prevalence and importance of ASCs may be gathered from Bourguignon's finding that 90% of cultures have institu tionalized forms of them. This is "a striking finding and suggests that we are, indeed, dealing with a matter of major importance, not merely a bit of anthropological esoterica" (11). One of the early assumptions that was often made about altered state inducing practices was that they exhibited equifinality. That is, many authors, including this one, mistakenly assumed that differing tech niques, such as various meditations, contemplations, and yogas, neces sarily resulted in equivalent states of consciousness. This largely reflected our ignorance of the broad range of possible ASCs that can be deliberately cultivated (Goleman). -

University of Groningen Genealogies Of

University of Groningen Genealogies of shamanism Boekhoven, J.W. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2011 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Boekhoven, J. W. (2011). Genealogies of shamanism: Struggles for power, charisma and authority. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Genealogies of Shamanism Struggles for Power, Charisma and Authority Cover photograph: Petra Giesbergen (Altaiskaya Byelka), courtesy of Petra Giesbergen (Altaiskaya Byelka) Cover design: Coltsfootmedia, Nynke Tiekstra, Noordwolde Book design: Barkhuis ISBN 9789077922880 © Copyright 2011 Jeroen Wim Boekhoven All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained here- in may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author. -

Resume 93/94

MADELINE DE JOLY madelinemail @earthlink .net www.madelinedejoly.com SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2012 “Untitled”, Iowa Contemporary, (ICON), Fairfield, IA 2005 "Memory ", Iowa Contemporary , ( ICON ) , Fairfield, IA 2005 " Memory", Unity Gallery, MUM, Fairfield, IA 2004 " Devotion", California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA 2002 "Infinite Knowledge: Veda and the Vedic Literature", Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA 1993 "Libraries of Confluence ", San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum, San Francisco, CA. 1991 "Collected Papers: Internal Energy", Kauffman Gallery, Houston, TX 1988 "Recent Work: All Dimensions", Art Collector, San Diego, CA 1987 "Process Of Sequence", Institute for Creative Arts, Fairfield, IA 1986 "De Joly: Evolution" , Carson-Sapiro Gallery Denver, CO 1984 "Qualities of the Unified Field", Kauffman Gallery, Houston, TX 1982 "De Joly: New Work", Art Collector, San Diego, CA 1980 "Experiments in Painting and Vacuum Formed Paper", University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 1979 "Vacuum Formed Paper", Boston World Art Exposition, Boston, MA 1972 "De Joly: Serial Landscapes", 36 Bromfield Street, Boston, MA 1971 "De Joly: Malachite Paintings", Brockton Art Museum Fuller Memorial, Brockton, MA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2011 “Encaustics with a Textile Sensibility”, Kimball Art Center, Park City, Utah 2011 “Gallery Artists” , Heidi Cho Gallery, Chelsea NYC, NY 2011 “Icon Invitational” Iowa Contemporary, Fairfield, IA 2010 “It's in the Pulp: The Art of Papermaking in Santa Cruz 1960-1980”, The Museum of Art and History, Santa Cruz, CA 2009 “The Art of the Book”, Donna Seager Gallery, San Raphael, CA 2009 “Altogether: Collage and Assemblage” ( Juror’s Award Recipient ) Santa Cruz Art League, Santa Cruz, CA. Nationally juried exhibit in conjunction with Santa Cruz County wide exhibitions on the same theme initiated by the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History. -

Residency Packet V.3 Pages

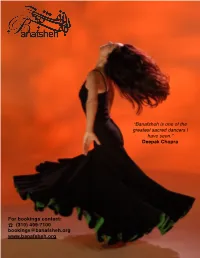

“Banafsheh is one of the greatest sacred dancers I have seen.” Deepak Chopra For bookings contact: ☎ (310) 499-7100 [email protected] www.banafsheh.org Banafsheh Internationally acclaimed Persian dance artist and educator, Banafsheh has been performing and teaching throughout North America, Europe, Turkey and Australia for a decade. In addition to contemporary Middle Eastern dance technique, Banafsheh teaches self-empowerment through dance, the inner dimensions of movement and experiential anatomy. Recognized for her fusion of high-level dance technique with spirituality, Banafsheh’s electrifying and wholly original dance style embodies the sensuous ecstasy of Persian Dance with the austere rigor of Sufi whirling – and includes elements of Flamenco, Tai Chi, and the Gurdjieff sacred Movements. Rumi lives through Banafsheh! Her movement is comprised in part by the Persian alphabet she has translated into gestures, which when put together she dances out poetic stanzas mostly from Rumi. With an MFA in Dance from UCLA and MA in Chinese Medicine, Banafsheh combines her dance expertise with the Taoist view of the internal functioning of the body, the Chakra system, Western Anatomy and Sufism to uncover movement that is at once healing, self-illuminating and connected to Spirit. The certification program she has founded, called Dance of Oneness® is about conscious embodiment. Known for her original movement vocabulary as well as high artistic and educational standards, Banafsheh comes from a long lineage of pioneering performing artists. Her father, the legendary Iranian filmmaker and actor, Parviz Sayyad is the most famous Iranian of his time. Banafsheh is one of the few bearers of authentic Persian dance in the world which is banned in her native country of Iran, and an innovator of Sufi dance previously only performed by men. -

Halekulani Okinawa Canyon Ranch Okinawa , Japan Lenox, Massachusetts

WHERE TO GO FOR ✺ CULTURED WELLNESS WHERE TO GO FOR ✺ HELP TO DEAL WITH GRIEF HALEKULANI OKINAWA CANYON RANCH OKINAWA , JAPAN LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORY: Although just opened in 2019, the resort’s emphasis on rejuvenation, Karate, a centuries-old practice that Living condominiums and six private Halekulani Okinawa’s home in Japan’s well-being, and cultural connection. focuses on strength and peace through residences, all designed with New Okinawa Prefecture—an archipelago fea- Located in the pristine Okinawa Kaigan physical movement and mindfulness, as England charm. turing 150+ islands in the East China Sea Quasi-National Park, the resort’s quiet, opposed to self-defense. Perhaps the most between Taiwan and Japan—imbues the clean-lined design showcases unbounded important aspect of the program is spend- EXTRAS: The focus here is on all aspects property with the region’s rich history, nature, teeming with uplifting sights and ing time in the great outdoors, especially of well-being, from an expansive, dating back to the 8th century. These sounds of wildlife and calm, cyan waters. via naturalist-guided explorations like 100,000-square-foot spa to an in-room islands were once called the “land of kayaking through Yambaru National Park pillow menu. Add-ons to the Pathway immortals,” in reference to the vitality FOR CULTURED WELLNESS: Halekulani on the Firefly Nature Discovery tour. programming are available, such as and longevity of their inhabitants. In Okinawa’s Secrets of Longevity program Travelers float under the lush canopy and, events, additional treatments, and sea- keeping with that now-scientifically is a series of immersive experiences tai- at sunset, experience thousands of fire- sonal outdoor activities—high ropes chal- proven reputation, today Okinawa is one lored to each guest, encouraging them to flies lighting up the evening sky.