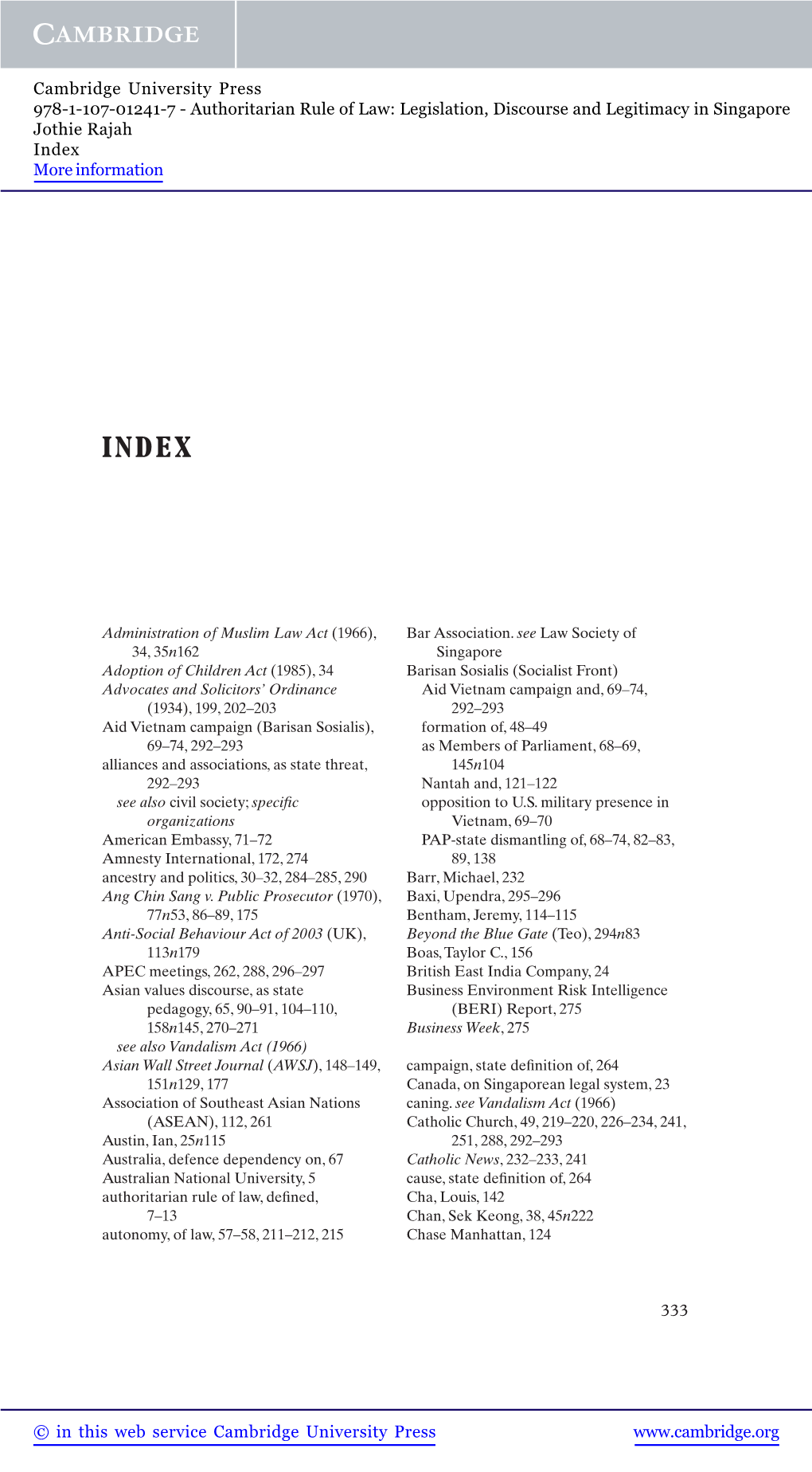

Authoritarian Rule of Law: Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore Jothie Rajah Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

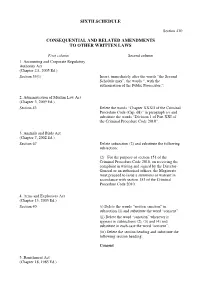

Sixth Schedule Consequential and Related

SIXTH SCHEDULE Section 430 CONSEQUENTIAL AND RELATED AMENDMENTS TO OTHER WRITTEN LAWS First column Second column 1. Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority Act (Chapter 2A, 2005 Ed.) Section 33(1) Insert, immediately after the words “the Second Schedule may”, the words “, with the authorisation of the Public Prosecutor,”. 2. Administration of Muslim Law Act (Chapter 3, 2009 Ed.) Section 43 Delete the words “Chapter XXXII of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 68)” in paragraph ( e) and substitute the words “Division 1 of Part XXI of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. 3. Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 7, 2002 Ed.) Section 67 Delete subsection (2) and substitute the following subsection: (2) For the purpose of section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010, on receiving the complaint in writing and signed by the Director- General or an authorised officer, the Magistrate must proceed to issue a summons or warrant in accordance with section 153 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. 4. Arms and Explosives Act (Chapter 13, 2003 Ed.) Section 40 (i) Delete the words “written sanction” in subsection (1) and substitute the word “consent”. (ii) Delete the word “sanction” wherever it appears in subsections (2), (3) and (4) and substitute in each case the word “consent”. (iii) Delete the section heading and substitute the following section heading: Consent 5. Banishment Act (Chapter 18, 1985 Ed.) Section 8(4) (i) Delete the words “section 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code” and substitute the words “section 116 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. (ii) Delete the marginal reference “Cap. 68.”. 6. Banking Act (Chapter 19, 2008 Ed.) Section 73 (i) Delete the word “Attorney-General” and substitute the words “Public Prosecutor”. -

3668212B-95De-4Ea1-9934

THE STATUTES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE CORRUPTION, DRUG TRAFFICKING AND OTHER SERIOUS CRIMES (CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS) ACT (CHAPTER 65A) (Original Enactment: Act 29 of 1992) REVISED EDITION 2000 (1st July 2000) Prepared and Published by THE LAW REVISION COMMISSION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISED EDITION OF THE LAWS ACT (CHAPTER 275) Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 CHAPTER 65A 2000 Ed. Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 2A. Meaning of “item subject to legal privilege” 3. Application 3A. Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office PART II CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS OF DRUG DEALING OR CRIMINAL CONDUCT 4. Confiscation orders 5. Confiscation orders for benefits derived from criminal conduct 5A. Confiscation order unaffected by confiscation order under Organised Crime Act 2015 6. Live video or live television links 7. Assessing benefits of drug dealing 8. Assessing benefits derived from criminal conduct 9. Statements relating to drug dealing or criminal conduct 10. Amount to be recovered under confiscation order 11. Interest on sums unpaid under confiscation order 12. Definition of principal terms used 13. Protection of rights of third party PART III ENFORCEMENT, ETC., OF CONFISCATION ORDERS 14. Application of procedure for enforcing fines 1 Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes 2000 Ed. (Confiscation of Benefits) CAP. 65A 2 Section 15. Cases in which restraint orders and charging orders may be made 16. Restraint orders 17. Charging orders in respect of land, capital markets products, etc. -

Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE (CHAPTER 68) (Original Enactment: Act 15 of 2010) REVISED EDITION 2012 (31st August 2012) An Act relating to criminal procedure. [2nd January 2011] PART I PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Procedure Code and is generally referred to in this Act as this Code. Interpretation 2. —(1) In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires — ―advocate‖ means an advocate and solicitor lawfully entitled to practise criminal law in Singapore; ―arrestable offence‖ and ―arrestable case‖ mean, respectively, an offence for which and a case in which a police officer may ordinarily arrest without warrant according to the third column of the First Schedule or under any other written law; ―bailable offence‖ means an offence shown as bailable in the fifth column of the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other written law, and ―non-bailable offence‖ means any offence other than a bailable offence; ―complaint‖ means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action under this Code that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed or is guilty of an offence; ―computer‖ has the same meaning as in the Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (Cap. 50A); [Act 3 of 2013 wef 13/03/2013] ―court‖ means the Court of Appeal, the High Court, a District Court or a Magistrate’s Court, as the case may be, which exercises criminal jurisdiction; ―criminal record‖ means the record of any — (a) conviction in any court, or subordinate military court established under section 80 of the Singapore Armed Forces Act (Cap. -

Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singaporeâ

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 10 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Jothie Rajah American Bar Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Rajah, Jothie, Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 135-165. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Abstract One of the funny things about living in the United States is that people say to me: ‘Singapore? Isn’t that where they flog you for chewing gum?’ – and I am always tempted to say yes. This question reveals what sticks in the popular US cultural imaginary about tiny, faraway Singapore. It is based on two events: first, in 1992, the sale of chewing gum was banned (Sale of Food [Prohibition of Chewing Gum] Regulations 1992), and second, in 1994, 18 year-old US citizen, Michael Fay, convicted of vandalism for having spray-painted some cars was sentenced to six strokes of the cane (Michael Peter Fay v Public Prosecutor).1 If Singapore already had a reputation for being a nanny state, then these two events simultaneously sharpened that reputation and confused the stories into the composite image through which Americans situate Singaporeans. -

2014 National History Bowl National Championships Round

United States Geography Olympiad Round 2 1. This location was where a 1956 airliner crash, the first in the U.S. to result in more than a hundred deaths, took place. Former Rough Rider Buckey O"Neill has a namesake cabin at this location, and the four "Mary Jane Colter Buildings" are also here. It was named by John Wesley Powell, who led a nine-man boat expedition through this site in 1869, and it has a "skywalk" maintained by the Hualapai tribe. The Pueblo people regarded this location as their holy site "Ongtupqa." Now a national park, it was called "beyond comparison" by Teddy Roosevelt. For the point, name this 277-mile wide, mile-deep fissure carved by the Colorado River in Arizona. ANSWER: Grand Canyon 052-13-94-30101 2. This region featured the construction of dueling world's tallest flagpoles in the 1980s. The U.S. staged Operation Paul Bunyan in this region after the 1976 "axe murder incident." Commandos snuck across it in 1968 in the failed Blue House Raid to assassinate a president later killed by his own security forces in 1979. This region has a "Joint Security Area" located at Panmunjeom, and it was created after a 1953 armistice. For the point, name this strip of land running along the 38th parallel north which separates two countries, including a Communist one led by Kim Jong-un. ANSWER: Korean Demilitarized Zone [or Korean DMZ; or Korean border; prompt on Panmunjeom until it is read; prompt on Korea] 052-13-94-30102 3. Roy Sesana is an activist for these people, many of whom were relocated to New Xade (cha-DAY) in 1997. -

US Department of State

1996 Human Rights Report: Singapore Page 1 of 12 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Singapore Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1996 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1997. SINGAPORE Singapore, a city-state of 3.4 million people, is a parliamentary republic in which politics is dominated by the People's Action Party (PAP), which has held power since Singapore gained autonomy from the United Kingdom in 1959. The PAP holds 77 of the 81 elected seats in Parliament. Goh Chok Tong completed his sixth year as Prime Minister. Lee Kuan Yew, who served as Prime Minister from independence in 1965 until 1990, remains active politically, holding the title of Senior Minister. The majority of the population is ethnic Chinese (78 percent), with Malays and Indians constituting substantial minorities. The Government maintains active internal security and military forces to counter perceived threats to the nation's security. It has frequently used security legislation to control a broad range of activity. The Internal Security Department (ISD) is responsible for enforcement of the Internal Security Act (ISA), including its provisions for detention without trial. All young males are subject to national service (mostly in the military). -

Download This Case As A

CSJ‐ 08 ‐ 0006.0 Settle or fight? Far Eastern Economic Review and Singapore In the summer of 2006, Hugo Restall—editor-in-chief of the monthly Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER)--published an article about a marginalized member of the political opposition in Singapore. The piece asserted that the Singapore government had a remarkable record of winning libel suits, which suggested a deliberate effort to neutralize opponents and subdue the press. Restall hypothesized that instances of corruption were going unreported because the incentive to investigate them was outweighed by the threat of an unwinnable libel suit. Singapore’s ruling family reacted swiftly. Lawyers for Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his father Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of modern Singapore, asserted that the article amounted to an accusation against their clients of personal incompetence and corruption. In a series of letters, the Lees’ counsel demanded a printed apology, removal of the offending article from FEER’s website, and compensation for damages. The magazine maintained that Restall’s piece was not libelous; nonetheless, it offered to take mitigating action short of the three demands. But the Lees remained adamant. Then, in a move whose timing defied coincidence, the government Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts informed FEER that henceforth it would be subject to new, and onerous, regulations. These actions were not without precedent. Singapore was an authoritarian, if prosperous, country. The Lee family--which claimed that the country’s ruling precepts were rooted in Confucianism, a philosophy that vested power in an enlightened ruler—tolerated no criticism. The Lees had been in charge for decades. -

Chapter 2 Essential Information for the Self-Represented Accused

CHAPTER 2 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED ACCUSED Guidebook For Accused In Person [11] A Guide To Representing Yourself In Court CHAPTER 2 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED ACCUSED (A) Should I hire a lawyer? Whether or not you wish to hire a lawyer is a personal decision. However, it is an important decision that should be made only after you have considered the pros and cons of the options available to you. Broadly speaking, when you are representing yourself, you would have to familiarise yourself with (i) the legal procedure and (ii) the substantive law (i.e. the laws and legal principles). This Guide will provide you with the necessary information on the legal procedure. However, it will not provide any insight on the substantive law and in particular, the defences available to you in law. If you intend to represent yourself, it is crucial that you know what your defences in law are. Even though you are representing yourself as a layman, the court cannot relax its procedural rules and standards for you. This means that you must be prepared to present your case as if you are a legally represented litigant. You must also be prepared to bear the full responsibility of preparing for and conducting your own case. The Judge may offer some guidance regarding the procedures of the trial but the Judge cannot act as your lawyer, i.e. the Judge cannot advise you on what you should do to successfully represent yourself. The role of the Judge is to ensure that you have a fair trial. -

Low Crime and Convictions in Singapore Zachary Reynolds

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2017 Intertwining Public Morality, Prosecutorial Discretion, and Punishment : Low Crime and Convictions in Singapore Zachary Reynolds Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Recommended Citation Reynolds, Zachary, "Intertwining Public Morality, Prosecutorial Discretion, and Punishment : Low Crime and Convictions in Singapore" (2017). International Immersion Program Papers. 61. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/international_immersion_program_papers/61 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERTWINING PUBLIC MORALITY, PROSECUTORIAL DISCRETION, AND PUNISHMENT: LOW CRIME AND CONVICTIONS IN SINGAPORE Zachary Reynolds 06/06/17 Introduction We have all likely heard of Singapore’s famously low crime rates. A point of well-deserved national pride, the small, island nation is committed to the safety of citizens and foreigners alike and consistently ranks as one of the safest cities in the world. To put this in perspective, an expatriate alumnus of the University of Chicago explained to me during my recent visit to Singapore1 that he was never concerned for the safety of his teenage daughter regardless of from where, when, or how she came home at night. Murder? Singapore has one of the lowest rates worldwide at 0.2 per 100,000 in 2013.2 Assault? Strictly controlled access to firearms makes deadly assault an extreme anomaly, and violent crime in general is virtually unheard of. -

Summary This Briefing Describes the Legality of Corporal Punishment of Children in Singapore Despite the Recommendations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child

SINGAPORE BRIEFING FOR THE HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW – 11th session, 2011 From Peter Newell, Coordinator, Global Initiative [email protected] Corporal punishment of children breaches their rights to respect for human dignity and physical integrity and to equal protection under the law. It is recognised by the Committee on the Rights of the Child and other treaty bodies, as well as by the UN Secretary General’s Study on Violence against Children, as a highly significant issue, both for asserting children’s status as rights holders and for the prevention of all forms of violence. The Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children (www.endcorporalpunishment.org) has been regularly briefing the Committee on the Rights of the Child on this issue since 2002, and since 2004 has similarly briefed the Committee Against Torture, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Human Rights Committee. There is growing progress now across all regions in challenging this very common form of violence against children. But we are concerned that many States persist in ignoring treaty body recommendations to prohibit and eliminate all corporal punishment. We hope that the UPR Process will give particular attention to states’ response, or lack of response, to the concluding observations from treaty bodies, on this and other key issues. In June 2006, the Committee on the Rights of the Child adopted General Comment No. 8 on “The right of the child to protection from corporal punishment and other cruel or degrading forms of punishment”, which emphasises the immediate obligation on states parties to prohibit all corporal punishment of children, including within the home. -

Criminal Legal Aid Scheme (CLAS) Was Set Assistance

What happens at the interview? When does CLAS assistance end? The Means Test CLAS assistance ends either when your case ends or During the interview with a CLAS officer, you will first when CLAS withdraws its assistance or you decide to be asked about your income, savings, property and proceed with your case without the aid of CLAS. other assets. This is called a Means Test. You will need to show proof of the means. Can I appeal if my application The Merits Test is rejected? After you have completed the Means Test, CLAS You may make an appeal against the decision by either: will have to decide whether giving you a lawyer would help your case ("Merits Test"). In order to (a) Emailing to CLAS at [email protected] citing determine this, a lawyer (called a Lead Lawyer) your application reference number, name and will ask you questions regarding your case. NRIC/Identification number; or by The Lead Lawyer may also give you some preliminary (b) Delivering your appeal in writing personally to Need Legal CLAS. Please state fully the grounds on which you are making Assistance? your appeal. Further enquiries Criminal For further enquiries, please call us during office hours at 6534 1564 or fax us at: 6534 5237. Legal You may also email us at: [email protected] Website: probono.lawsociety.org.sg Aid legal advice on your matter, as well as preliminary advice on the procedures moving forward with regard to your Disclaimer: matter. Scheme The information contained herein only represents general and basic information on CLAS as of It is essential that all information you give to the Lead January 2016. -

Inhuman Sentencing of Children in Singapore Report Prepared for the Child Rights Information Network ( November 2010

Inhuman sentencing of children in Singapore Report prepared for the Child Rights Information Network (www.crin.org), November 2010 Introduction Persons convicted of an offence committed under the age of 18 cannot be sentenced to capital punishment but may be sentenced to corporal punishment and life imprisonment. The main laws governing juvenile justice are the Children and Young Persons Act 1993, the Penal Code 1872 and the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. The Penal Code sets the minimum age of criminal responsibility at 7.1 The Children and Young Persons Act defines a child as under 14, a young person as 14-15.2 The Criminal Procedure Code defines a juvenile as from 7 to 15.3 Persons aged 16-17 are tried as adults. Legality of inhuman sentencing Death penalty Capital punishment is unlawful for child offenders. Article 314 of the Criminal Procedure Code states: “A sentence of death must not be passed or recorded against an accused convicted of an offence if the court has reason to believe that, at the time the offence was committed, he was below the age of 18 years, but instead the court must sentence him to life imprisonment.” Corporal punishment Corporal punishment is lawful as a sentence for juvenile offenders. Under the Children and Young Persons Act, children aged 7-15 are tried by the Juvenile Court, with the exception of offences triable only by the High Court, such as murder, rape, drug trafficking or armed robbery.4 The High Court, but not the Juvenile Court, may sentence the child to be caned.5 Persons aged 16-17 are tried as adults.