Low Crime and Convictions in Singapore Zachary Reynolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2010 - 2011 Contents

Annual Report 2010 - 2011 Contents 2 Foreword by the Attorney-General 6 Remembrance and Congratulations 10 Our Mission, Vision and Core Values 13 Our Roles 15 Our Corporate Structure A. AGC’s Management Team B. Six Legal Divisions and Two Non-Legal Divisions 29 Our Key Milestones A. As The Government’s Chief Legal Adviser and Counsel i. AGC’s Advisory Work ii. AGC’s Involvement in Litigation iii. AGC in Negotiations iv. AGC as Legislative Draftsman B. As Public Prosecutor C. In Performing Other Assigned Duties of a Legal Character D. Our Corporate Resources 61 Our Training, Development and Outreach 67 The Ties that Bind Us 71 Key Figures for 2010-2011 A. Corporate Awards B. Performance Indicators C. Financial Indicators for FY2010-FY2011 Attorney-General’s Chambers ANNUAL REPORT 2010 - 2011 1 FOREWORD BY THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL As we look back on these past years, the taxation policies and policies concerning adjust to these changes so that we can function perceptible increase in the complexity of our casino regulation. Cross-Divisional teams effectively. work is particularly striking. This growing were also engaged to deal with cases before complexity has in turn given rise to two the Singapore Courts when we were required With this in mind, I have intensified the consequences, which I elaborate on below. to address constitutional challenges and also commitment of my Chambers to the training, to defend Singapore’s judiciary in the face of development and specialisation of our officers contempt. so that we are well placed to support the THE NEED FOR Government with the highest level of legal iNTER-dIVISIONAL This is perhaps a reality that is ultimately to be services. -

The Criminal Procedure Code 2010

(2011) 23 SAcLJ Modernising the Criminal Justice Framework 23 MODERNISING THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE FRAMEWORK The Criminal Procedure Code 2010 The concept of “balancing” prevalent in criminal justice discourse is premised on a paradigm where “state” and “individual” interests are perpetually in conflict. This article outlines the key components of the new Criminal Procedure Code 2010 and discusses another dimension of the state- individual relationship. Rather than being inherently incompatible, synergistic common goals can, on occasion, be pursued between the State and an accused. The article will also consider areas in the Criminal Procedure Code 2010 where conflicts between “state” and “individual” interests have in fact arisen, and will outline the pragmatic approach that has been adopted towards their resolution. Melanie CHNG* LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore), LLM (Harvard); Advocate & Solicitor (Singapore); Assistant Director, Ministry of Law. The criminal process is at the heart of the criminal justice system. It is not only a subject of great practical importance; it is also a reflection of our ideals and values as to the way in which we can accord justice to both the guilty and to the innocent.[1] I. Introduction 1 The recent legislative amendments to Singapore’s Criminal Procedure Code (“CPC”) signify a new chapter in the continuing evolution of Singapore’s criminal justice process. The new Criminal Procedure Code 2010 (“New CPC”),2 which came into force on * The opinions expressed in this article are those of its author and are not representative of the official position or policies of the Singapore government. The author is grateful to Mr Amarjeet Singh SC, Ms Jennifer Marie SC, Mr Bala Reddy, Professor Michael Hor, Mr Subhas Anandan, Ms Valerie Thean and Mr Desmond Lee for their invaluable comments on an earlier draft of this article. -

Pre-Trial Conferences

04 PRE-TRIAL CONFERENCES (A) What is a Pre-Trial Conference (PTC) (B) How should I prepare for the PTC? (C) What should I expect during the hearing? (D) Criminal Case Disclosure Conference (CCDC) 32 uideoo for Accused in Person CHAPTER 4 PRE-TRIAL CONFERENCES A flow chart of the criminal process in brief Mentions Court Claim Trial Date will be given Plead Guilty First PTC to take plea of guilt CCDC Does Not Apply CCDC Applies Unanimous agreement required for CCDC Unanimous agreement required for CCDC Plead Guilty Decline to Decline to Participate Participate Agree to Participate to Agree Regular PTCs to settle administrative Case for Prosecution matters prepared and given to you Agree to Participate to Agree Claim Trial Case for Defence must be prepared and given to Prosecution See “Agree to Participate” Prosecution to give you documents in their case Trial Date Fixed and statements made by you during investigations Trial 33 uideoo for Accused in Person (A) What is a Pre-Trial Conference (PTC)? If you claim trial during the mention of your case, the Mentions Court will fix the case for a Pre-Trial Conference (PTC). The purpose of the PTC is to prepare you and the Prosecution for trial and to settle any administrative matters before the trial date is fixed. (B) How should I prepare for the PTC? Prior to the PTC, you should consider whether you wish to address the following matters during the PTC: (i) Check if the Prosecution intends to make use of any written statement given by you to the police and if so, you may request for a copy of the statement. -

Corporal Punishment of Children in Singapore

Corporal punishment of children in Singapore: Briefing for the Universal Periodic Review, 24th session, 2016 From Dr Sharon Owen, Research and Information Coordinator, Global Initiative, [email protected] The legality and practice of corporal punishment of children violates their fundamental human rights to respect for human dignity and physical integrity and to equal protection under the law. Under international human rights law – the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights instruments – states have an obligation to enact legislation to prohibit corporal punishment in all settings, including the home. In Singapore, corporal punishment of children is lawful, despite repeated recommendations to prohibit it by the Committee on the Rights of the Child and recommendations made during the 1st cycle UPR of Singapore (which the Government rejected). Law reform in 2010/2011 re-authorised corporal punishment in some settings. We hope the Working Group will note with concern the legality of corporal punishment of children in Singapore. We hope states will raise the issue during the review in 2016 and make a specific recommendation that Singapore clearly prohibit all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home and repeal all legal defences and authorisations for the use of corporal punishment. 1 Review of Singapore in the 1st cycle UPR (2011) and progress since then 1.1 Singapore was reviewed in the first cycle of the Universal Periodic Review in 2011 (session 11). The issue of corporal punishment of children was raised in the compilation of UN information1 and in the summary of stakeholders’ information.2 The Government rejected recommendations to prohibit corporal punishment of children.3 1.2 Prohibiting and eliminating all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home – through law reform and other measures – is a key obligation under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights instruments, though it is one frequently evaded by Governments. -

Report of the Official Parliamentary Delegation to Singapore and Indonesia 28 October—8 November 2008

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Report of the Official Parliamentary Delegation to Singapore and Indonesia 28 October—8 November 2008 March 2009 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-0-642-79153-5 Contents FRONTPAGES Membership of the Delegation.............................................................................................................vi Objectives .........................................................................................................................................viii Singapore..................................................................................................................................viii Indonesia ..................................................................................................................................viii List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ix REPORT 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 Singapore—Background Information...................................................................................... 1 Geography and Population ......................................................................................................... 1 Political Structure ........................................................................................................................ 2 Economic Overview ................................................................................................................... -

ANNUAL CRIME BRIEF 2020 Singapore Remains One of the Safest Cities in the World

POLICE NEWS RELEASE _________________________________________________________________ ANNUAL CRIME BRIEF 2020 Singapore Remains One of the Safest Cities in the World Overall Crime Rate increased due to rise in scam cases Singapore remains one of the safest cities in the world. Singapore was ranked first in the Gallup’s 2020 Global Law and Order report for the seventh consecutive year, with 97% of residents reporting that they felt safe walking home alone in their neighbourhood at night, as compared to an average of 69% worldwide.1 The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2020 also ranked Singapore first for order and security.2 2. In 2020, the total number of reported crimes increased by 6.5% to 37,409 cases, from 35,115 cases in 2019. The Overall Crime Rate also increased, with 658 cases per 100,000 population in 2020, compared to 616 cases per 100,000 population in 2019.3 3. The increase in the number of reported crimes was due to a rise in scam cases. In particular, online scams saw a significant increase as Singaporeans carried out more online transactions due to the COVID-19 situation. 4 Please see Annex A for the statistics on the top ten scam types. 4. If scam cases were excluded, the total number of reported crimes in 2020 would have decreased by 15.3% to 21,653 from 25,570 in 2019. Decrease in physical crimes and more crime-free days 5. There was a decrease in physical crimes in 2020. 201 days were free from three confrontational crimes, namely snatch theft, robbery and housebreaking, an increase of 23 days compared to 178 days in 2019. -

The Definitive Guide to Cybersecurity in Singapore

The Definitive Guide to Cybersecurity in Singapore 4 Things You Need to Know About the New Singapore Cybersecurity Bill Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 History of Cybersecurity Legislation in Singapore 4-6 Need for Legislation 7-8 Objectives of the Omnibus Bill 9 The Key Parts of the Proposed Legislation 10-12 How Resolve Systems Can Help 13 Conclusion 14 About Us and References 15 Glossary Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) - Formed in April 2015 under the Prime Minister’s Office, it is the national encag y overseeing cybersecurity strategy, operations, education, outreach, and ecosystem development. Critical Information Infrastructures (CII) – A computer or computer system necessary for continuous delivery of essential services which Singapore relies on; the loss or compromise of which will lead to a debilitating impact on national security, defense, foreign relations, economy, public health, public safety, or public order of Singapore. Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (CMCA) - An Act for securing computer material against unauthorized access or modification. Provides authority to measure and ensure cybersecurity. National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) – Monitors and analyzes cyber threat landscape to maintain cyber situational awareness and anticipate future threats. Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) – Oversees the development of the infocomm media, cybersecurity, and design sectors of Singapore. Who’s Who in Singapore Mr. Lee Hsien Loong - Prime Minister of Singapore Mr. David Koh – Singapore’s Defense Cyber Chief leading Defense Cyber Organization Mr. Teo Chee Hean - Deputy Prime Minister and Coordinating Minister for National Security Dr. Yaacob Ibrahim - Minister for Communications and Information; Minister-in-charge of Cyber Security Executive Summary Singapore is a highly digitized country and is only becoming more so as they expand upon their goal of being a Smart Nation. -

Juvenile Justice: a Study of National Judiciaries for The

JUVENILE JUSTICE: A STUDY OF NATIONAL JUDICIARIES FOR THE UNITED NATIONS ASIA AND FAR EAST INSTITUTE FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRIME AND THE TREATMENT OF OFFENDERS A focus on Singapore and selected comparisons with California (USA) & Australia Joseph Ozawa* I. SINGAPORE When Singapore is mentioned in various parts of the world, there are certain predicable responses, often focusing on Singaporean laws or the judicial system. “Oh, the place that makes chewing gum illegal!” or “The country that caned Michael Fey for spraying graffiti!” or “The nation that makes it a crime not to flush a toilet!” However, despite these sometimes amusing though derisive attributions, taking decisive action on minor infractions was subsequently popularized and advocated by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in their 1982 treatise entitled, “broken windows.” Here Wilson and Kelling argued that actually tolerating broken windows will actually result in larger and more extensive crimes. A successful anti-crime strategy is to fix problems when they are still minor. New York City government used much of Wilson’s and Kelling’s theory in “cleaning up” New York streets. Whatever the end product of “small laws,” Singapore has 12 times the population of Vancouver but just half the crime rate. It is difficult finding many recent international crime comparisons and as researchers know, comparing crime rates is filled with methodological problems. However, in general, in 1993, the juvenile delinquency rate in Singapore was rated at 538 per 100,000 persons whereas Japan was rated 1,220 per 100,000 and the USA 5,460 per 100,000. -

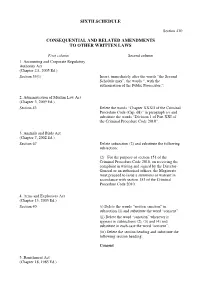

Sixth Schedule Consequential and Related

SIXTH SCHEDULE Section 430 CONSEQUENTIAL AND RELATED AMENDMENTS TO OTHER WRITTEN LAWS First column Second column 1. Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority Act (Chapter 2A, 2005 Ed.) Section 33(1) Insert, immediately after the words “the Second Schedule may”, the words “, with the authorisation of the Public Prosecutor,”. 2. Administration of Muslim Law Act (Chapter 3, 2009 Ed.) Section 43 Delete the words “Chapter XXXII of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 68)” in paragraph ( e) and substitute the words “Division 1 of Part XXI of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. 3. Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 7, 2002 Ed.) Section 67 Delete subsection (2) and substitute the following subsection: (2) For the purpose of section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010, on receiving the complaint in writing and signed by the Director- General or an authorised officer, the Magistrate must proceed to issue a summons or warrant in accordance with section 153 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. 4. Arms and Explosives Act (Chapter 13, 2003 Ed.) Section 40 (i) Delete the words “written sanction” in subsection (1) and substitute the word “consent”. (ii) Delete the word “sanction” wherever it appears in subsections (2), (3) and (4) and substitute in each case the word “consent”. (iii) Delete the section heading and substitute the following section heading: Consent 5. Banishment Act (Chapter 18, 1985 Ed.) Section 8(4) (i) Delete the words “section 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code” and substitute the words “section 116 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. (ii) Delete the marginal reference “Cap. 68.”. 6. Banking Act (Chapter 19, 2008 Ed.) Section 73 (i) Delete the word “Attorney-General” and substitute the words “Public Prosecutor”. -

3668212B-95De-4Ea1-9934

THE STATUTES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE CORRUPTION, DRUG TRAFFICKING AND OTHER SERIOUS CRIMES (CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS) ACT (CHAPTER 65A) (Original Enactment: Act 29 of 1992) REVISED EDITION 2000 (1st July 2000) Prepared and Published by THE LAW REVISION COMMISSION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISED EDITION OF THE LAWS ACT (CHAPTER 275) Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 CHAPTER 65A 2000 Ed. Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 2A. Meaning of “item subject to legal privilege” 3. Application 3A. Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office PART II CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS OF DRUG DEALING OR CRIMINAL CONDUCT 4. Confiscation orders 5. Confiscation orders for benefits derived from criminal conduct 5A. Confiscation order unaffected by confiscation order under Organised Crime Act 2015 6. Live video or live television links 7. Assessing benefits of drug dealing 8. Assessing benefits derived from criminal conduct 9. Statements relating to drug dealing or criminal conduct 10. Amount to be recovered under confiscation order 11. Interest on sums unpaid under confiscation order 12. Definition of principal terms used 13. Protection of rights of third party PART III ENFORCEMENT, ETC., OF CONFISCATION ORDERS 14. Application of procedure for enforcing fines 1 Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes 2000 Ed. (Confiscation of Benefits) CAP. 65A 2 Section 15. Cases in which restraint orders and charging orders may be made 16. Restraint orders 17. Charging orders in respect of land, capital markets products, etc. -

Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE (CHAPTER 68) (Original Enactment: Act 15 of 2010) REVISED EDITION 2012 (31st August 2012) An Act relating to criminal procedure. [2nd January 2011] PART I PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Procedure Code and is generally referred to in this Act as this Code. Interpretation 2. —(1) In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires — ―advocate‖ means an advocate and solicitor lawfully entitled to practise criminal law in Singapore; ―arrestable offence‖ and ―arrestable case‖ mean, respectively, an offence for which and a case in which a police officer may ordinarily arrest without warrant according to the third column of the First Schedule or under any other written law; ―bailable offence‖ means an offence shown as bailable in the fifth column of the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other written law, and ―non-bailable offence‖ means any offence other than a bailable offence; ―complaint‖ means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action under this Code that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed or is guilty of an offence; ―computer‖ has the same meaning as in the Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (Cap. 50A); [Act 3 of 2013 wef 13/03/2013] ―court‖ means the Court of Appeal, the High Court, a District Court or a Magistrate’s Court, as the case may be, which exercises criminal jurisdiction; ―criminal record‖ means the record of any — (a) conviction in any court, or subordinate military court established under section 80 of the Singapore Armed Forces Act (Cap. -

Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singaporeâ

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 10 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Jothie Rajah American Bar Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Rajah, Jothie, Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 135-165. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Abstract One of the funny things about living in the United States is that people say to me: ‘Singapore? Isn’t that where they flog you for chewing gum?’ – and I am always tempted to say yes. This question reveals what sticks in the popular US cultural imaginary about tiny, faraway Singapore. It is based on two events: first, in 1992, the sale of chewing gum was banned (Sale of Food [Prohibition of Chewing Gum] Regulations 1992), and second, in 1994, 18 year-old US citizen, Michael Fay, convicted of vandalism for having spray-painted some cars was sentenced to six strokes of the cane (Michael Peter Fay v Public Prosecutor).1 If Singapore already had a reputation for being a nanny state, then these two events simultaneously sharpened that reputation and confused the stories into the composite image through which Americans situate Singaporeans.