The Caning of Michael Fay: Can Singapore's Punishment Withstand the Scrutiny of International Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporal Punishment in Tennessee

Office of Research and Education Accountability JUSTIN P. WILSON, COMPTROLLER Corporal Punishment in Tennessee Lauren Spires Legislative Research Analyst March 2018 Table of Contents Executive summary 2 Box: Definitions for corporal punishment and students with disabilities 2 Key findings 3 Policy considerations 6 Section 1: Tennessee’s corporal punishment policy 7 Box: TCA 49-6-4103 7 Box: TCA 49-6-4104 7 School board policies on corporal punishment 7 Exhibit 1: Where corporal punishment is allowed and not allowed per school 8 board policy, 2017-18 school year Tennessee School Boards Association model policies on corporal 8 punishment Variation in district policies 9 Box: Charter schools and corporal punishment 9 Section 2: Variation between board policy and use 10 Variation between board policies and affirming corporal punishment use 10 Variation between affirming corporal punishment use and reported data 11 Exhibit 2: Corporal punishment in Tennessee schools, 2013-14 school year 11 Exhibit 3: Tennessee school districts | Variance among board policies and 12 corporal punishment use Tennessee compared to other states 12 Exhibit 4: The United States of America | State laws on corporal punishment 13 Exhibit 5: The United States of America | Corporal punishment use by school 14 district, 2013-14 school year Section 3: Beyond local board policy | How decisions are made 14 about corporal punishment Exhibit 6: How decisions regarding the use of corporal punishment are made in 15 Tennessee schools Survey of directors of schools 16 Exhibit 7: -

A GUIDE to the CORRECTION of YOUNG GENTLEMEN Or, the Successful Administration of Physical Discipline to Males, by Females

• A GUIDE TO . THE CORRECTION OF YOUNG GENTLEMEN The Successful Administration ofPhysical' 'Discipline to Males-bY,Females! WRITTEN BYA LADY OVER 30 ILLUSTRATIONS A GUIDE To THE CORRECTION OF YOUNG GENTLEMEN or, The Successful Administration Of Physical Discipline To Males, By Females WRITTEN ByA LADY WITH ILLUSTRATIONS By A FORMER PUPIL Reprinted from the original Private Edition of 1924 First British publication 1991 by Delectus Books Limited London, England Copyright ©Delectus Books 1991 Illustrations © Delectus Books 1991 All Rights Reserved N o part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any:form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Printed by Bishops Printers, Portsmouth Delectus Books, 27 Old Gloucester Street London W C IN IXX To APHRODITE .PHILOMASTRIX Introduction to the 1991 Reprint i Foreword ix \ I: T.he Triple Goddess 1 II: The Eternal Boy 11 III: A Closed World 17 IV: Clothing &' The Regime 25 v: Non-Corporal Punishments .32 "- VI: Corporal Punishment ~ .42 VII: The Birch 79 VIII, The Aftermatb 93 -1 IX: A Miscellany ~ , 95 ~.; . r ~ l' il ApPENDICES t I A: The Calculation ofOffences 102 I' B: A Sample Contraet 103 I An Aunt Does Her Duty 105 . I l~............,.~ ~...,..AW"AIIIJ . INTRODUCTION TO THE 1991 REPRINT HE HISTORY OF A Guide to the Correction of.Young Gentlemen is a tale of survival by purest chance against all the odds. Few books can have had T such an unpromising start in life. First produced, if not precisely published, in 1924-in a private edition limited to 100 copies, dark green morocco bindings with over thirty hand-drawn illustrations-c-not a single copy had been sold or distributed to customers before the entire consignment, togeth er with much else, was seized by police in a raid on the privately-owned printing works belonging to eccentric dilettante publisher Gerald Percival Hamer. -

Corporal Punishment of Children in Singapore

Corporal punishment of children in Singapore: Briefing for the Universal Periodic Review, 24th session, 2016 From Dr Sharon Owen, Research and Information Coordinator, Global Initiative, [email protected] The legality and practice of corporal punishment of children violates their fundamental human rights to respect for human dignity and physical integrity and to equal protection under the law. Under international human rights law – the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights instruments – states have an obligation to enact legislation to prohibit corporal punishment in all settings, including the home. In Singapore, corporal punishment of children is lawful, despite repeated recommendations to prohibit it by the Committee on the Rights of the Child and recommendations made during the 1st cycle UPR of Singapore (which the Government rejected). Law reform in 2010/2011 re-authorised corporal punishment in some settings. We hope the Working Group will note with concern the legality of corporal punishment of children in Singapore. We hope states will raise the issue during the review in 2016 and make a specific recommendation that Singapore clearly prohibit all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home and repeal all legal defences and authorisations for the use of corporal punishment. 1 Review of Singapore in the 1st cycle UPR (2011) and progress since then 1.1 Singapore was reviewed in the first cycle of the Universal Periodic Review in 2011 (session 11). The issue of corporal punishment of children was raised in the compilation of UN information1 and in the summary of stakeholders’ information.2 The Government rejected recommendations to prohibit corporal punishment of children.3 1.2 Prohibiting and eliminating all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home – through law reform and other measures – is a key obligation under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights instruments, though it is one frequently evaded by Governments. -

![[Wednesday, 13 August 2003] 9825 the THC in Marijuana and The](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1235/wednesday-13-august-2003-9825-the-thc-in-marijuana-and-the-711235.webp)

[Wednesday, 13 August 2003] 9825 the THC in Marijuana and The

[Wednesday, 13 August 2003] 9825 The THC in marijuana and the brain’s endogenous cannabinoids work in much the same way, but THC is far stronger and more persistent than anandamide, which, like most neurotransmitters, is designed to break down very soon after its release. (Chocolate, of all things, seems to slow this process, which might account for its own subtle mood-altering properties.) What this suggests is that smoking marijuana may overstimulate the brain’s built-in forgetting faculty, exaggerating its normal operations. This is no small thing. Indeed, I would venture that, more than any other single quality, it is the relentless moment-by-moment forgetting, this draining of the pool of sense impressions almost as quickly as it fills, that gives the experience of consciousness under marijuana its peculiar texture. It helps account for the sharpening of sensory perceptions, for the aura of profundity in which cannabis bathes the most ordinary insights, and, perhaps most important of all, for the sense that time has slowed and even stopped. On the previous page, the book states - ‘If we could hear the squirrel’s heartbeat, the sound of the grass growing, we should die of that roar,’ George Eliot once wrote. Our mental health depends on a mechanism for editing the moment-by-moment ocean of sensory data flowing into our consciousness down to a manageable trickle of the noticed and remembered. The cannabinoid network appears to be part of that mechanism, vigilantly sifting the vast chaff of sense impressions from the kernels of perception we need to remember if we’re to get through the day and get done what needs to be done. -

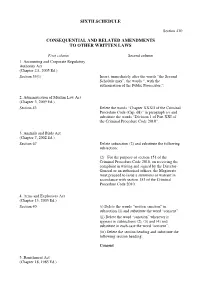

Sixth Schedule Consequential and Related

SIXTH SCHEDULE Section 430 CONSEQUENTIAL AND RELATED AMENDMENTS TO OTHER WRITTEN LAWS First column Second column 1. Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority Act (Chapter 2A, 2005 Ed.) Section 33(1) Insert, immediately after the words “the Second Schedule may”, the words “, with the authorisation of the Public Prosecutor,”. 2. Administration of Muslim Law Act (Chapter 3, 2009 Ed.) Section 43 Delete the words “Chapter XXXII of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 68)” in paragraph ( e) and substitute the words “Division 1 of Part XXI of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. 3. Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 7, 2002 Ed.) Section 67 Delete subsection (2) and substitute the following subsection: (2) For the purpose of section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010, on receiving the complaint in writing and signed by the Director- General or an authorised officer, the Magistrate must proceed to issue a summons or warrant in accordance with section 153 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. 4. Arms and Explosives Act (Chapter 13, 2003 Ed.) Section 40 (i) Delete the words “written sanction” in subsection (1) and substitute the word “consent”. (ii) Delete the word “sanction” wherever it appears in subsections (2), (3) and (4) and substitute in each case the word “consent”. (iii) Delete the section heading and substitute the following section heading: Consent 5. Banishment Act (Chapter 18, 1985 Ed.) Section 8(4) (i) Delete the words “section 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code” and substitute the words “section 116 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. (ii) Delete the marginal reference “Cap. 68.”. 6. Banking Act (Chapter 19, 2008 Ed.) Section 73 (i) Delete the word “Attorney-General” and substitute the words “Public Prosecutor”. -

“May Cause Lasting Physical Harm” The

“May cause lasting physical harm” The Determination stated that ‘Ariel’s Sponsored Caning’ constitutes restricted material on the basis of the following claim: “Where there is clearer sight of more ‘serious’ marking of the skin, particularly to the latter part of the video, where there is focus on injury that has been caused; the raising of the skin and the heavier marking. This constitutes material which “involves the infliction of pain or acts which may cause lasting physical harm, whether real or (in a sexual context) simulated”, which is prohibited by the BBFC in a pornographic work. “ Corporal punishment such as that depicted on Dreams of Spanking is intended to cause temporary, transient pain. If any marks are inflicted, they will heal within a reasonable timeframe, usually between a couple of days and a couple of weeks. The assumption that this sort of activity “may cause lasting harm” indicates a remarkable level of ignorance. All our performers are experienced BDSM players who know their own bodies and their own tolerances well. Usually performers prefer not to receive lasting marks on videos hoots, as most enthusiasts prefer not to play again until any marks from the previous session have fully healed. Dreams of Spanking makes it a point of principle to operate within our performers' experience and comfort zones, and full negotiation and explicit, enthusiastic consent is shown as a matter of course in our performer interviews and behind the scenes videos accompanying each of the spanking films. Let us examine Ariel Anderssen's bottom at the start and end of “Ariel's Sponsored Caning”: (click on any of the following images to open them at a high resolution in your web browser) These marks were quick to appear, and quick to disappear. -

3668212B-95De-4Ea1-9934

THE STATUTES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE CORRUPTION, DRUG TRAFFICKING AND OTHER SERIOUS CRIMES (CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS) ACT (CHAPTER 65A) (Original Enactment: Act 29 of 1992) REVISED EDITION 2000 (1st July 2000) Prepared and Published by THE LAW REVISION COMMISSION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISED EDITION OF THE LAWS ACT (CHAPTER 275) Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 CHAPTER 65A 2000 Ed. Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 2A. Meaning of “item subject to legal privilege” 3. Application 3A. Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office PART II CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS OF DRUG DEALING OR CRIMINAL CONDUCT 4. Confiscation orders 5. Confiscation orders for benefits derived from criminal conduct 5A. Confiscation order unaffected by confiscation order under Organised Crime Act 2015 6. Live video or live television links 7. Assessing benefits of drug dealing 8. Assessing benefits derived from criminal conduct 9. Statements relating to drug dealing or criminal conduct 10. Amount to be recovered under confiscation order 11. Interest on sums unpaid under confiscation order 12. Definition of principal terms used 13. Protection of rights of third party PART III ENFORCEMENT, ETC., OF CONFISCATION ORDERS 14. Application of procedure for enforcing fines 1 Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes 2000 Ed. (Confiscation of Benefits) CAP. 65A 2 Section 15. Cases in which restraint orders and charging orders may be made 16. Restraint orders 17. Charging orders in respect of land, capital markets products, etc. -

Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE (CHAPTER 68) (Original Enactment: Act 15 of 2010) REVISED EDITION 2012 (31st August 2012) An Act relating to criminal procedure. [2nd January 2011] PART I PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Procedure Code and is generally referred to in this Act as this Code. Interpretation 2. —(1) In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires — ―advocate‖ means an advocate and solicitor lawfully entitled to practise criminal law in Singapore; ―arrestable offence‖ and ―arrestable case‖ mean, respectively, an offence for which and a case in which a police officer may ordinarily arrest without warrant according to the third column of the First Schedule or under any other written law; ―bailable offence‖ means an offence shown as bailable in the fifth column of the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other written law, and ―non-bailable offence‖ means any offence other than a bailable offence; ―complaint‖ means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action under this Code that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed or is guilty of an offence; ―computer‖ has the same meaning as in the Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (Cap. 50A); [Act 3 of 2013 wef 13/03/2013] ―court‖ means the Court of Appeal, the High Court, a District Court or a Magistrate’s Court, as the case may be, which exercises criminal jurisdiction; ―criminal record‖ means the record of any — (a) conviction in any court, or subordinate military court established under section 80 of the Singapore Armed Forces Act (Cap. -

Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singaporeâ

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 10 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Jothie Rajah American Bar Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Rajah, Jothie, Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 135-165. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Abstract One of the funny things about living in the United States is that people say to me: ‘Singapore? Isn’t that where they flog you for chewing gum?’ – and I am always tempted to say yes. This question reveals what sticks in the popular US cultural imaginary about tiny, faraway Singapore. It is based on two events: first, in 1992, the sale of chewing gum was banned (Sale of Food [Prohibition of Chewing Gum] Regulations 1992), and second, in 1994, 18 year-old US citizen, Michael Fay, convicted of vandalism for having spray-painted some cars was sentenced to six strokes of the cane (Michael Peter Fay v Public Prosecutor).1 If Singapore already had a reputation for being a nanny state, then these two events simultaneously sharpened that reputation and confused the stories into the composite image through which Americans situate Singaporeans. -

2014 National History Bowl National Championships Round

United States Geography Olympiad Round 2 1. This location was where a 1956 airliner crash, the first in the U.S. to result in more than a hundred deaths, took place. Former Rough Rider Buckey O"Neill has a namesake cabin at this location, and the four "Mary Jane Colter Buildings" are also here. It was named by John Wesley Powell, who led a nine-man boat expedition through this site in 1869, and it has a "skywalk" maintained by the Hualapai tribe. The Pueblo people regarded this location as their holy site "Ongtupqa." Now a national park, it was called "beyond comparison" by Teddy Roosevelt. For the point, name this 277-mile wide, mile-deep fissure carved by the Colorado River in Arizona. ANSWER: Grand Canyon 052-13-94-30101 2. This region featured the construction of dueling world's tallest flagpoles in the 1980s. The U.S. staged Operation Paul Bunyan in this region after the 1976 "axe murder incident." Commandos snuck across it in 1968 in the failed Blue House Raid to assassinate a president later killed by his own security forces in 1979. This region has a "Joint Security Area" located at Panmunjeom, and it was created after a 1953 armistice. For the point, name this strip of land running along the 38th parallel north which separates two countries, including a Communist one led by Kim Jong-un. ANSWER: Korean Demilitarized Zone [or Korean DMZ; or Korean border; prompt on Panmunjeom until it is read; prompt on Korea] 052-13-94-30102 3. Roy Sesana is an activist for these people, many of whom were relocated to New Xade (cha-DAY) in 1997. -

The Constitutionality of School Corporal Punishment of Children As a Betrayal of Brown V

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 36 Article 9 Issue 1 Fall 2004 2004 The onsC titutionality of School Corporal Punishment of Children as a Betrayal of Brown v. Board of Education Susan H. Bitensky Michigan State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation Susan H. Bitensky, The Constitutionality of School Corporal Punishment of Children as a Betrayal of Brown v. Board of Education, 36 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 201 (2004). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol36/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Constitutionality of School Corporal Punishment of Children as a Betrayal of Brown v. Board of Education Susan H. Bitensky* I. INTRODUCTION American judicial history, like any institutional history, has had its shameful moments and its glorious ones, with plenty in-between. Some of the worst and best of these decisions have concerned race relations. Consider such low points for the United States Supreme Court as Dred Scott v. Sandford' and the Japanese-American restriction cases.2 The 3 former, among other things, essentially upheld slavery as constitutional while the latter upheld the constitutionality of the mass internment of and curfew imposed upon persons of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast during World War I. -

Can the Caning Punishment Execution in Aceh Meet Its Objective?

Mazahib, Vol 19, No.1 (June 2020), Pp. 41-78 http://doi.org/10.21093/mj.v19i1.2055 https://journal.iain-samarinda.ac.id/index.php/mazahib/index P-ISSN: 1829-9067 | E-ISSN: 2460-6588 DETERRING OR ENTERTAINING? Can the Caning Punishment Execution in Aceh Meet its Objective? Faradilla Fadlia1, Ismar Ramadani2, Novi Susilawati3, Novita Sari4 1 Universitas Syiah Kuala ([email protected]); 2 Universitas Almuslim Bireuen ([email protected]); 3 Universitas Syiah Kuala ([email protected]); 4Universitas Syiah Kuala ([email protected]) Abstract This article probes whether the implementation of the caning sentence in Aceh may reach its objective of deterrent effect given the way the execution conducted. From the field observation, the flogging was not much different from entertainment. The mass gathered in one place to watch the execution; they include children, street vendors, researchers, and journalists. There was a stage, VIP seats for guests, loudspeakers, administrative arrangements, and the caning punishment procession. Using a qualitative research approach with an in-depth interview method, it seeks to understand how the community involved in the caning execution was and how the government was designed the sentence as such and why. It finds that while the government saw the caning law as the implementation of Islamic sharia in Aceh, the people perceived its execution more as entertainment. The government has used the caning sentence execution as a demonstration of power, often for a political gain, because it emphasizes its presence not only as of the guardian of shari’a for Acehnese but also as a devout politician who keeps his political promises.