Decolonizing Singapore Art, Practice and Curriculum in Post-Colonial Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore Biennale 2016 Artists and Artwork Highlights ‘An Atlas of Mirrors’ Explained Through 9 Curatorial Sub-Themes Singapore, 22 September 2016 – The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) today revealed a list of 62 artists and art collectives and selected artwork highlights of the Singapore Biennale 2016 (SB2016), one of Asia’s most exciting contemporary visual art exhibitions. Titled An Atlas of Mirrors, SB2016 draws on diverse artistic viewpoints that trace the migratory and intertwining relationships within the region, and reflect on shared histories and current realities with East and South Asia. SB2016 will present 60 artworks that respond to An Atlas of Mirrors, including 49 newly commissioned and adapted artworks. The SB2016 artworks, spanning various mediums, will be clustered around nine sub-themes and presented across seven venues – Singapore Art Museum and SAM at 8Q, Asian Civilisations Museum, de Suantio Gallery at SMU, National Museum of Singapore, Stamford Green, and Peranakan Museum. The full artist list can be found in Annex A. SB2016 Artists In addition to the 30 artists already announced, SB2016 will include Chou Shih Hsiung, Debbie Ding, Faizal Hamdan, Abeer Gupta, Subodh Gupta, Gregory Halili, Agan Harahap, Kentaro Hiroki, Htein Lin, Jiao Xingtao, Sanjay Kak, Marine Ky, H.H. Lim, Lim Soo Ngee, Made Djirna, Made Wianta, Perception3, Niranjan Rajah, S. Chandrasekaran, Sharmiza Abu Hassan, Nilima Sheikh, Praneet Soi, Adeela Suleman, Melati Suryodarmo, Nobuaki Takekawa, Jack Tan, Tan Zi Hao, Ryan Villamael, Wen Pulin, Xiao Lu, Zang Honghua, and Zulkifle Mahmod. SB2016 artists are from 18 countries and territories in Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia. -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Download SB2016 Exhibition Guide

ORGANISED BY COMMISSIONED BY SUPPORTED BY SINGAPORE SINGAPORE BIENNALE 2016 BIENNALE 2016 ARTISTS AHMAD FUAD OSMAN 59 KENTARO HIROKI 21, 49 SHARMIZA ABU HASSAN 27 MALAYSIA THAILAND/JAPAN MALAYSIA MARTHA ATIENZA 31 HTEIN LIN 46 DO HO SUH 28 PHILIPPINES/NETHERLANDS MYANMAR SOUTH KOREA/UNITED STATES/ UNITED KINGDOM AZIZAN PAIMAN 41 JIAO XINGTAO 59 MALAYSIA CHINA ADEELA SULEMAN 49 PAKISTAN RATHIN BARMAN 51 SAKARIN KRUE-ON 61 INDIA THAILAND MELATI SURYODARMO 23 INDONESIA HEMALI BHUTA 26 MARINE KY 57 SEA OF INDIA CAMBODIA/FRANCE EDDY SUSANTO 25 JAPAN INDONESIA SOUTH KOREA JAPAN BUI CONG KHANH 50 PHASAO LAO 35 VIETNAM TCHEU SIONG NOBUAKI TAKEKAWA 48 LAOS JAPAN YELLOW SEA DAVID CHAN 54 CHINA SINGAPORE H.H. LIM 21 JACK TAN 47 MALAYSIA/ITALY SINGAPORE/UNITED KINGDOM CHIA CHUYIA 41 MALAYSIA/SWEDEN LIM SOO NGEE 20 MELISSA TAN 42 PAKISTAN SINGAPORE SINGAPORE CHOU SHIH HSIUNG 29 TAIWAN MADE DJIRNA 27 TAN ZI HAO 28 EAST INDONESIA MALAYSIA CHINA SEA ADE DARMAWAN 48 TAIWAN BANGLADESH INDONESIA MADE WIANTA 25 TITARUBI 34 HONG KONG INDONESIA INDONESIA DENG GUOYUAN 34 INDIA TROPIC OF CANCER MYANMAR CHINA MAP OFFICE 23 TUN WIN AUNG & WAH NU 32 LAOS HONG KONG/FRANCE MYANMAR DEBBIE DING 55 SINGAPORE/UNITED KINGDOM MUNEM WASIF 42 RYAN VILLAMAEL 36 BANGLADESH PHILIPPINES 3 PAGE THAILAND PHILIPPINES PATRICIA PEREZ EUSTAQUIO 22 PHILIPPINE SEA PHILIPPINES PHUONG LINH NGUYEN 33 WEN PULIN 43 VIETNAM BAY VIETNAM ZANG HONGHUA OF SOUTH BENGAL FAIZAL HAMDAN 47 CHINA CAMBODIA CHINA SEA BRUNEI NI YOUYU 30 CHINA WITNESS TO PARADISE 2016: 44 ANDAMAN DEX FERNANDEZ 26 NILIMA SHEIKH, PRANEET SOI, SRI LANKA SEA PHILIPPINES PERCEPTION3 55 ABEER GUPTA & SANJAY KAK SINGAPORE INDIA MALAYSIA BRUNEI FYEROOL DARMA 33 SINGAPORE PALA POTHUPITIYE 24 XIAO LU 20 SRI LANKA CHINA SINGAPORE SUBODH GUPTA 54 INDIA QIU ZHIJIE 29 PANNAPHAN YODMANEE 31 EQUATOR CHINA THAILAND GREGORY HALILI 30 PHILIPPINES NIRANJAN RAJAH 50 HARUMI YUKUTAKE 22 MALAYSIA/CANADA JAPAN HAN SAI POR 37 SINGAPORE ARAYA RASDJARMREARNSOOK 36 ZULKIFLE MAHMOD 24 INDONESIA JAVA FLORES SEA SEA THAILAND SINGAPORE AGAN HARAHAP 32 INDONESIA S. -

Introducing the Museum Roundtable

P. 2 P. 3 Introducing the Hello! Museum Roundtable Singapore has a whole bunch of museums you might not have heard The Museum Roundtable (MR) is a network formed by of and that’s one of the things we the National Heritage Board to support Singapore’s museum-going culture. We believe in the development hope to change with this guide. of a museum community which includes audience, museum practitioners and emerging professionals. We focus on supporting the training of people who work in We’ve featured the (over 50) museums and connecting our members to encourage members of Singapore’s Museum discussion, collaboration and partnership. Roundtable and also what you Our members comprise over 50 public and private can get up to in and around them. museums and galleries spanning the subjects of history and culture, art and design, defence and technology In doing so, we hope to help you and natural science. With them, we hope to build a ILoveMuseums plan a great day out that includes community that champions the role and importance of museums in society. a museum, perhaps even one that you’ve never visited before. Go on, they might surprise you. International Museum Day #museumday “Museums are important means of cultural exchange, enrichment of cultures and development of mutual understanding, cooperation and peace among peoples.” — International Council of Museums (ICOM) On (and around) 18 May each year, the world museum community commemorates International Museum Day (IMD), established in 1977 to spread the word about the icom.museum role of museums in society. Be a part of the celebrations – look out for local IMD events, head to a museum to relax, learn and explore. -

Exhibition Guide

ArTScience MuSeuM™ PreSenTS ceLeBrATinG SinGAPOre’S cOnTeMPOrArY ArT Exhibition GuidE Detail, And We Were Like Those Who Dreamed, Donna Ong Open 10am to 7pm daily | www.MarinaBaySands.com/ArtScienceMuseum Facebook.com/ArtScienceMuseum | Twitter.com/ArtSciMuseum WELCOME TO PRUDENTIAL SINGAPORE EYE Angela Chong Angela chong is an installation artist who Prudential Singapore Eye presents a with great conceptual confidence. uses light, sound, narrative and interactive comprehensive survey of Singapore’s Works range across media including media to blur the line between fiction and contemporary art scene through the painting, installation and photography. reality. She has shown work in Amsterdam Light Festival in the netherlands; Vivid works of some of the country’s most The line-up includes a number of Festival in Sydney; 100 Points of Light Festival innovative artists. The exhibiting artists who are gaining an international in Melbourne; cP international Biennale in artists were chosen from over 110 following, to artists who are just Jakarta, indonesia, and iLight Marina Bay in submissions and represent a selection beginning to be known. Like all the other Singapore. of the best contemporary art in Prudential Eye exhibitions, Prudential 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an interactive light sculpture Singapore. Prudential Singapore Eye is Singapore Eye aims to bring to light which allows multiple players of all ages to the first major exhibition in a year of a new and exciting contemporary art play Tic-Tac-Toe with one another. cultural celebrations of the nation’s 50th scene and foster greater appreciation of anniversary. Singapore’s visual art scene both locally and internationally. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, 2014 The works of the exhibiting artists demonstrate versatility, with many of the artists working experimentally Jeremy Sharma Jeremy Sharma works primarily as a conceptual painter. -

How Nations Learn Praise for the Book

How Nations Learn Praise for the Book ‘The chapters examine how industrial latecomers have crafted strategic and pragmatic policy frameworks to unleash the universal passion for learning into business organ- izational practices that drive production capability development and foster innovation dynamics. The transformational experiences described in the book offer a multitude of ways in which learning is organized and applied to advance a nation’s productive structures and build competitive advantage in the global economy.’ Michael H Best, Professor Emeritus, Author of How Growth Really Happens: The Making of Economic Miracles through Production, Governance and Skills, Winner of the 2018 Schumpeter Prize ‘The analysis of development and catching-up has finally shifted away from sur- real problems of ‘optimal’ market-driven allocation of resources, toward the processes of learning and capability accumulation. This is an important contribution in this perspec- tive: And yet another nail into the coffinofthe“Washington Consensus”.’ Giovanni Dosi, Professor of Economics, Scuola Superiore Sant’ Anna, Pisa, Italy ‘Industrialisation has always been fundamental to sustained economic growth. It separates the world into high and low-income economies. To create inclusive pros- perity, we urgently need to understand How Nations Learn. State-supported innovation is not only cardinal for catch-up, but also to abate climate breakdown (through crowding in new businesses, nurturing experimentation, and ensuring public benefits). By studying the economic history of technological advancement in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, this book makes a powerful case for industrial policy.’ Dr Alice Evans, Lecturer in International Development, King’s College London ‘How Nations Learn is a book based on big ideas. -

Art of Tang Da Wu

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ art of Tang Da Wu Wee, C. J. Wan‑Ling 2018 Wee, C. J. W.‑L. (2018). Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ artof Tang Da Wu. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286‑306. doi:10.1017/S0307883317000591 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144518 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883317000591 © 2018 International Federation for Theatre Research. All rights reserved. This paper was published by Cambridge University Press in Theatre Research International and is made available with permission of International Federation for Theatre Research. Downloaded on 27 Sep 2021 10:02:22 SGT Accepted and finalized version of: Wee, C. J. W.-L. (2018). ‘Body and communication: The “Ordinary” Art of Tang Da Wu’. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286-306. C. J. W.-L. Wee [email protected] Body and Communication: The ‘Ordinary’ Art of Tang Da Wu Abstract What might the contemporary performing body look like when it seeks to communicate and to cultivate the need to live well within the natural environment, whether the context of that living well is framed and set upon either by longstanding cultural traditions or by diverse modernizing forces over some time? The Singapore performance and visual artist Tang Da Wu has engaged with a present and a region fractured by the predations of unacceptable cultural norms – the consequences of colonial modernity or the modern nation-state taking on imperial pretensions – and the subsumption of Singapore society under capitalist modernization. Tang’s performing body both refuses the diminution of time to the present, as is the wont of the forces he engages with, and undertakes interventions by sometimes elusive and ironic means – unlike some overdetermined contemporary performance art – that reject the image of the modernist ‘artist as hero’. -

From Colonial Segregation to Postcolonial ‘Integration’ – Constructing Ethnic Difference Through Singapore’S Little India and the Singapore ‘Indian’

FROM COLONIAL SEGREGATION TO POSTCOLONIAL ‘INTEGRATION’ – CONSTRUCTING ETHNIC DIFFERENCE THROUGH SINGAPORE’S LITTLE INDIA AND THE SINGAPORE ‘INDIAN’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY BY SUBRAMANIAM AIYER UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2006 ---------- Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Thesis Argument 3 Research Methodology and Fieldwork Experiences 6 Theoretical Perspectives 16 Social Production of Space and Social Construction of Space 16 Hegemony 18 Thesis Structure 30 PART I - SEGREGATION, ‘RACE’ AND THE COLONIAL CITY Chapter 1 COLONIAL ORIGINS TO NATION STATE – A PREVIEW 34 1.1 Singapore – The Colonial City 34 1.1.1 History and Politics 34 1.1.2 Society 38 1.1.3 Urban Political Economy 39 1.2 Singapore – The Nation State 44 1.3 Conclusion 47 2 INDIAN MIGRATION 49 2.1 Indian migration to the British colonies, including Southeast Asia 49 2.2 Indian Migration to Singapore 51 2.3 Gathering Grounds of Early Indian Migrants in Singapore 59 2.4 The Ethnic Signification of Little India 63 2.5 Conclusion 65 3 THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONIAL NARRATIVE IN SINGAPORE – AN IDEOLOGY OF RACIAL ZONING AND SEGREGATION 67 3.1 The Construction of the Colonial Narrative in Singapore 67 3.2 Racial Zoning and Segregation 71 3.3 Street Naming 79 3.4 Urban built forms 84 3.5 Conclusion 85 PART II - ‘INTEGRATION’, ‘RACE’ AND ETHNICITY IN THE NATION STATE Chapter -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Annual Report 2010-2011 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi Published by: Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi This Annual Report can also be accessed at website: www.mea.gov.in Designed and printed by: Cyberart Informations Pvt. Ltd. 1517 Hemkunt Chambers, 89 Nehru Place, New Delhi 110 019 E mail: [email protected] Website: www.cyberart.co.in Telefax: 0120-4231676 Contents Introduction and Synopsis i-xviii 1 India’s Neighbours 1 2 South East Asia and the Pacific 18 3 East Asia 26 4 Eurasia 32 5 The Gulf, West Asia and North Africa 41 6 Africa (South of Sahara) 50 7 Europe and European Union 66 8 The Americas 88 9 United Nations and International Organizations 105 10 Disarmament and International Security Affairs 120 11 Multilateral Economic Relation 125 12 SAARC 128 13 Technical and Economic Cooperation and Development Partnership 131 14 Investment and Technology Promotion 134 15 Energy Security 136 16 Policy Planning and Research 137 17 Protocol 140 18 Consular, Passport and Visa Services 147 19 Administration and Establishment 150 20 Right to Information and Chief Public Information Office 153 21 e-Governance and Information Technology 154 22 Coordination 155 23 External Publicity 156 24 Public Diplomacy 158 25 Foreign Service Institute 165 26 Implementation of Official Language Policy and Propagation of Hindi Abroad 167 27 Third Heads of Missions’ (HoMS) Conference 170 28 Indian Council for Cultural Relations 171 29 Indian Council of World Affairs 176 30 Research and Information -

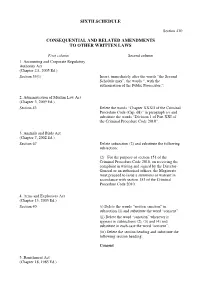

Sixth Schedule Consequential and Related

SIXTH SCHEDULE Section 430 CONSEQUENTIAL AND RELATED AMENDMENTS TO OTHER WRITTEN LAWS First column Second column 1. Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority Act (Chapter 2A, 2005 Ed.) Section 33(1) Insert, immediately after the words “the Second Schedule may”, the words “, with the authorisation of the Public Prosecutor,”. 2. Administration of Muslim Law Act (Chapter 3, 2009 Ed.) Section 43 Delete the words “Chapter XXXII of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 68)” in paragraph ( e) and substitute the words “Division 1 of Part XXI of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. 3. Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 7, 2002 Ed.) Section 67 Delete subsection (2) and substitute the following subsection: (2) For the purpose of section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010, on receiving the complaint in writing and signed by the Director- General or an authorised officer, the Magistrate must proceed to issue a summons or warrant in accordance with section 153 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. 4. Arms and Explosives Act (Chapter 13, 2003 Ed.) Section 40 (i) Delete the words “written sanction” in subsection (1) and substitute the word “consent”. (ii) Delete the word “sanction” wherever it appears in subsections (2), (3) and (4) and substitute in each case the word “consent”. (iii) Delete the section heading and substitute the following section heading: Consent 5. Banishment Act (Chapter 18, 1985 Ed.) Section 8(4) (i) Delete the words “section 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code” and substitute the words “section 116 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. (ii) Delete the marginal reference “Cap. 68.”. 6. Banking Act (Chapter 19, 2008 Ed.) Section 73 (i) Delete the word “Attorney-General” and substitute the words “Public Prosecutor”. -

3668212B-95De-4Ea1-9934

THE STATUTES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE CORRUPTION, DRUG TRAFFICKING AND OTHER SERIOUS CRIMES (CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS) ACT (CHAPTER 65A) (Original Enactment: Act 29 of 1992) REVISED EDITION 2000 (1st July 2000) Prepared and Published by THE LAW REVISION COMMISSION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISED EDITION OF THE LAWS ACT (CHAPTER 275) Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 CHAPTER 65A 2000 Ed. Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 2A. Meaning of “item subject to legal privilege” 3. Application 3A. Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office PART II CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS OF DRUG DEALING OR CRIMINAL CONDUCT 4. Confiscation orders 5. Confiscation orders for benefits derived from criminal conduct 5A. Confiscation order unaffected by confiscation order under Organised Crime Act 2015 6. Live video or live television links 7. Assessing benefits of drug dealing 8. Assessing benefits derived from criminal conduct 9. Statements relating to drug dealing or criminal conduct 10. Amount to be recovered under confiscation order 11. Interest on sums unpaid under confiscation order 12. Definition of principal terms used 13. Protection of rights of third party PART III ENFORCEMENT, ETC., OF CONFISCATION ORDERS 14. Application of procedure for enforcing fines 1 Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes 2000 Ed. (Confiscation of Benefits) CAP. 65A 2 Section 15. Cases in which restraint orders and charging orders may be made 16. Restraint orders 17. Charging orders in respect of land, capital markets products, etc. -

Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE (CHAPTER 68) (Original Enactment: Act 15 of 2010) REVISED EDITION 2012 (31st August 2012) An Act relating to criminal procedure. [2nd January 2011] PART I PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Procedure Code and is generally referred to in this Act as this Code. Interpretation 2. —(1) In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires — ―advocate‖ means an advocate and solicitor lawfully entitled to practise criminal law in Singapore; ―arrestable offence‖ and ―arrestable case‖ mean, respectively, an offence for which and a case in which a police officer may ordinarily arrest without warrant according to the third column of the First Schedule or under any other written law; ―bailable offence‖ means an offence shown as bailable in the fifth column of the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other written law, and ―non-bailable offence‖ means any offence other than a bailable offence; ―complaint‖ means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action under this Code that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed or is guilty of an offence; ―computer‖ has the same meaning as in the Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (Cap. 50A); [Act 3 of 2013 wef 13/03/2013] ―court‖ means the Court of Appeal, the High Court, a District Court or a Magistrate’s Court, as the case may be, which exercises criminal jurisdiction; ―criminal record‖ means the record of any — (a) conviction in any court, or subordinate military court established under section 80 of the Singapore Armed Forces Act (Cap.