Migrants at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamental Rights Report 2020 Is Published in English

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT ― 2020 REPORT — A great deal of information on the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the FRA website at fra.europa.eu The Fundamental Rights Report 2020 is published in English. — FRA’s annual Fundamental Rights Report is based on the results of its own primary quantitative and qualitative research and on secondary desk research at national level conducted by FRA’s multidisciplinary research network, FRANET. Relevant data on international obligations in the area of human rights are available via FRA's European Union Fundamental Rights Information System (EFRIS) at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/databases/efris/. © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the Agency is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 Print ISBN 978-92-9474-895-9 ISSN 2467-2351 doi:10.2811/18138 TK-AL-20-001-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9474-894-2 ISSN 2467-236X doi:10.2811/570216 TK-AL-20-001-EN-N Photos: see page 228 for copyright information PRINTED ON PROCESS CHLORINE-FREE RECYCLED PAPER (PCF) Contents 1 TEN YEARS ON: UNLOCKING THE CHARTER’S FULL POTENTIAL ..................................................................4 1.1. -

ATLAS of MIGRATION Facts and Figures About People on the Move

ATLAS OF MIGRATION Facts and figures about people on the move ESCAPE, WORK, FUTURE IMPRINT The ATLAS OF MIGRATION is published by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Berlin, Germany Chief executive editors: Johanna Bussemer, Dorit Riethmüller Editors: Christian Jakob (coordination), Stefanie Kron, Wenke Christoph Managing editor: Dietmar Bartz Art Director: Ellen Stockmar English Editor: Paul Mundy Proofreader: Maria Lanman Fact checking: Infotext Berlin Contributors: Friedrich Burschel, Wenke Christoph, Johanna Elle, Sabine Hess, Christian Jakob, Bernd Kasparek, Stefanie Kron, Laura Lambert, Ramona Lenz, Carlos Lopes, Sowmya Maheswaran, Johanna Neuhauser, Mario Neumann, Jochen Oltmer, Maria Oshana, Massimo Perinelli, Maximilian Pichl, Matthias Schmidt-Sembdner, Helen Schwenken, Maurice Stierl, Christian Stock, and a team of authors. Cover image: Ellen Stockmar The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishing organization. Editorial responsibility (V. i. S. d. P.): Alrun Kaune-Nüßlein, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Second English edition, October 2019 Produced by Bonifatius GmbH Druck – Buch – Verlag, Paderborn Climate-neutral printing on 100 percent recycled paper. This material (except the cover picture) is licensed under Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported“ (CC BY-SA 4.0). For the licence agreement, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode, and a summary (not a substitute) at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en. Individual graphics from this atlas may be reproduced if the attribution ”Bartz/Stockmar, CC BY 4.0“ is placed next to the graphic (in case of modification: ”Bartz/Stockmar (M), CC BY 4.0“). ATLAS DER MIGRATION Daten und Fakten über Menschen in Bewegung FOR FREE DELIVERIES AND DOWNLOADS: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Franz-Mehring-Platz 1, 10243 Berlin, Germany www.rosalux.de/atlasofmigration FLUCHT, ARBEIT, The ATLAS OF MIGRATION is also published as ATLAS DER MIGRATION in German. -

The Castaways from Hell

THE CASTAWAYS FROM HELL Testimonies collected on the Aquarius AUTHOR PHOTOS MARIE RAJABLAT LAURIN SCHMID Hausa proverb “Idan ka ga wani yana gudu kuma yana so ya fada cikin wuta, yana nufin cewa abin da yake bin shi yafi wuta” “If you see someone fleeing who would rather fall into the fire, this means that whatever it is that is chasing him is worse than the fire.” FOREWORD One of the three essential missions of SOS MEDITERRANEE is to bear witness... Marie Rajablat's work, far from naive optimism or voyeurism, shows how crucial this mission of bearing witness to the situation in the Mediterranean is. Having read this book, it is impossible not to understand that any reservations around the rescue of those who are drowning in the Mediterranean, “mare nostrum”, are ridiculous or even irresponsible. In fact, their rescue is not an option, but a necessity, in the philosophical sense that simply leaving them to drown at sea is “something which cannot be”. When it comes to migration policies, everything is open to debate, questioning or argument; everything except the immediate rescue and disembarkation at a safe port of these human beings, these torn families who are fleeing hell. In this context, things are simple: we have no choice other than to act, unless of course we yield to the thoughtless temptation to lose our soul, to avoid facing facts, and thus to feed the poison that insidiously undermines Europe and our societies, in the same way that the desperate lack of will and strategic vision of our politicians does. -

Immigrazione: Accoglienza O Contenimento ? Un Nuovo Approccio

I DOSSIER DI PARTECIPAGIRE.NET IMMIGRAZIONE: ACCOGLIENZA O CONTENIMENTO ? UN NUOVO APPROCCIO Di Massimo D’ANGELO 1 Sommario Parte I ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 UN PIANO MARSHALL PER L’IMMIGRAZIONE: UNA NOVITÀ, UNA SOLUZIONE, UN’ILLUSIONE O COS’ALTRO?.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Un Piano Marshall per l’immigrazione è una novità? ..................................................................... 4 Chi propone un Piano Marshall per l’immigrazione? ...................................................................... 4 Obiettivo finale: riduzione dei flussi migratori ............................................................................... 6 Quando si potrebbe introdurre un Piano Marshall per l’immigrazione? ........................................ 6 Ogni tanto c’è qualcuno che chiede un Piano Marshall per l’aiuto ai paesi più poveri.................. 7 Alcune domande di fondo ................................................................................................................ 9 I problemi di efficacia e di impatto dell’aiuto e un Piano Marshall per l’immigrazione .............. 11 NOTE .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Parte II .................................................................................................................................................. -

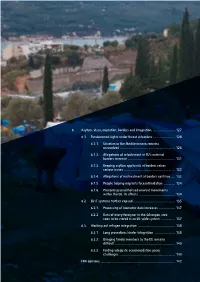

Chapter 6. Asylum, Visas, Migration, Borders and Integration

6 Asylum, visas, migration, borders and integration �������������������������� 127 6�1� Fundamental rights under threat at borders ������������������������� 128 6�1�1� Situation in the Mediterranean remains unresolved ����������������������������������������������������������������� 128 6�1�2� Allegations of refoulement at EU’s external borders increase �������������������������������������������������������� 131 6�1�3� Keeping asylum applicants at borders raises serious issues ������������������������������������������������������������ 132 6�1�4� Allegations of mistreatment at borders continue ���� 133 6�1�5� People helping migrants face intimidation ������������� 134 6�1�6� Preventing unauthorised onward movements within the EU: its effects ������������������������������������������ 134 6�2� EU IT systems further expand ������������������������������������������������� 135 6�2�1� Processing of biometric data increases ������������������� 137 6�2�2� Data of every foreigner in the Schengen area soon to be stored in an EU-wide system ���������������� 137 6�3� Working out refugee integration �������������������������������������������� 138 6�3�1� Long procedures hinder integration ������������������������ 138 6�3�2� Bringing family members to the EU remains difficult ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 140 6�3�3� Finding adequate accommodation poses challenges ������������������������������������������������������������������ 140 FRA opinions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations*

Migrants at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations* Claudio Deiana, Vikram Maheshri, Giovanni Mastrobuoni§ December 22, 2020 Abstract The Central Mediterranean Sea is the world's most dangerous crossing for irregular migrants. In response to mounting deaths, European nations intensified search and rescue operations in 2013. We develop a model of irregular migration to identify the effects of these operations. Leveraging plausibly exogenous variation from rapidly varying crossing conditions, we find that smugglers responded by sending boats in adverse weather and shifting from seaworthy boats to flimsy rafts. In doing so, these operations induced more crossings, ultimately offsetting their intended safety benefits. A more successful policy should restrict the supply of rafts and expand legal alternatives to irregular migration. Keywords: Central Mediterranean sea crossings, international, undocumented, irregular migration, search and rescue operations, rubber boats, deaths JEL codes: F22 (International Migration); H12 (Crisis Management). * We thank Cevat Aksoy, Samuel Bazzi, Giacomo Calzolari, Gordon Hanson, Tim Hatton, Andrea Ichino, Sandra Rozo and various seminar and conference audiences for their valuable feedback. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors only and do not reflect the views of, or involve any responsibility for, the institutions to which they are affiliated. Any errors are the fault of the authors only. University of Cagliari, [email protected] University of Houston, [email protected] § Collegio -

ATLAS of MIGRATION Facts and Figures About People on the Move

ATLAS OF MIGRATION Facts and figures about people on the move ESCAPE, WORK, FUTURE IMPRINT The ATLAS OF MIGRATION is published by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Berlin, Germany Chief executive editors: Johanna Bussemer, Dorit Riethmüller Editors: Christian Jakob (coordination), Stefanie Kron, Wenke Christoph Managing editor: Dietmar Bartz Art Director: Ellen Stockmar English Editor: Paul Mundy Proofreader: Maria Lanman Fact checking: Infotext Berlin Contributors: Friedrich Burschel, Wenke Christoph, Johanna Elle, Sabine Hess, Christian Jakob, Bernd Kasparek, Stefanie Kron, Laura Lambert, Ramona Lenz, Carlos Lopes, Sowmya Maheswaran, Johanna Neuhauser, Mario Neumann, Jochen Oltmer, Maria Oshana, Massimo Perinelli, Maximilian Pichl, Matthias Schmidt-Sembdner, Helen Schwenken, Maurice Stierl, Christian Stock, and a team of authors. Cover image: Ellen Stockmar The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishing organization. Editorial responsibility (V. i. S. d. P.): Alrun Kaune-Nüßlein, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation First English edition, June 2019 Produced by Bonifatius GmbH Druck – Buch – Verlag, Paderborn Climate-neutral printing on 100 percent recycled paper. This material (except the cover picture) is licensed under Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported“ (CC BY-SA 4.0). For the licence agreement, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode, and a summary (not a substitute) at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en. Individual graphics from this atlas may be reproduced if the attribution ”Bartz/Stockmar, CC BY 4.0“ is placed next to the graphic (in case of modification: ”Bartz/Stockmar (M), CC BY 4.0“). ATLAS DER MIGRATION Daten und Fakten über Menschen in Bewegung FOR FREE DELIVERIES AND DOWNLOADS: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Franz-Mehring-Platz 1, 10243 Berlin, Germany www.rosalux.de/atlasofmigration FLUCHT, ARBEIT, The ATLAS OF MIGRATION is also published as ATLAS DER MIGRATION in German. -

Migration at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations∗

Migration at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations∗ Claudio Deiana,y Vikram Maheshri,z Giovanni Mastrobuonix November 2019 Abstract The Central Mediterranean Sea is the most dangerous crossing for irregular migrants in the world. At any point in time, over half a million potential migrants wait in Libya to travel to Italy with the aid of human smugglers. In response to high profile shipwrecks and mounting deaths, European nations intensified search and rescue operations beginning in 2013. We develop a model of irregular migration in order to identify the effects of these operations on activity along this smuggling route. Leveraging plausibly exogenous variation from rapidly varying weather and sea conditions, we find that smugglers responded to these operations by shifting from seaworthy wooden boats to flimsy inflatable rafts. In doing so, these operations induced more crossings and had the ultimate effect of entirely offsetting the intended safety benefits of search and rescue operations, which were captured at least in part by smugglers. Keywords: Central Mediterranean sea crossings, international, undocumented, irregular migration, search and rescue operations, rubber boats, deaths JEL codes: F22 (International Migration); H12 (Crisis Management). ∗ We thank Giacomo Calzolari, Gordon Hanson, Tim Hatton, Andrea Ichino, Samuel Bazzi, Cevat Aksoy and various seminar and conference audiences for their valuable feedback. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors only and do not reflect the views of, or involve any -

Migrants at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations∗

Migrants at Sea: Unintended Consequences of Search and Rescue Operations∗ Claudio Deiana,y Vikram Maheshri,z Giovanni Mastrobuonix September 23, 2020 Abstract The Central Mediterranean Sea is the most dangerous crossing in the world for irregular migrants. Every day, over half a million potential migrants wait in Libya to travel to Italy with the aid of human smugglers. In response to high profile shipwrecks and mounting deaths, European nations intensified search and rescue operations in 2013. We develop a model of irregular migration in order to identify the effects of these operations on activity along this smuggling route. Leveraging plausibly exogenous variation from rapidly varying weather and tidal conditions, we find that smugglers responded to these operations by sending out boats in worse weather conditions and, when inflatable rafts became readily available, by shifting from seaworthy wooden boats to flimsy inflatable rafts. In doing so, these operations induced more crossings and had the ultimate effect of offsetting many of the intended safety benefits of search and rescue operations, which were captured at least in part by smugglers. A more successful policy should target the demand side by expanding legal alternatives to irregular migration and improving domestic conditions in migrants' home countries. Keywords: Central Mediterranean sea crossings, international, undocumented, irregular migration, search and rescue operations, rubber boats, deaths JEL codes: F22 (International Migration); H12 (Crisis Management). ∗ We thank Giacomo Calzolari, Gordon Hanson, Tim Hatton, Andrea Ichino, Samuel Bazzi, Cevat Aksoy and various seminar and conference audiences for their valuable feedback. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors only and do not reflect the views of, or involve any responsibility for, the institutions to which they are affiliated. -

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT ― 2020 REPORT — a Great Deal of Information on the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Is Available on the Internet

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT ― 2020 REPORT — A great deal of information on the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the FRA website at fra.europa.eu The Fundamental Rights Report 2020 is published in English. — FRA’s annual Fundamental Rights Report is based on the results of its own primary quantitative and qualitative research and on secondary desk research at national level conducted by FRA’s multidisciplinary research network, FRANET. Relevant data on international obligations in the area of human rights are available via FRA's European Union Fundamental Rights Information System (EFRIS) at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/databases/efris/. © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the Agency is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 Print ISBN 978-92-9474-895-9 ISSN 2467-2351 doi:10.2811/18138 TK-AL-20-001-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9474-894-2 ISSN 2467-236X doi:10.2811/570216 TK-AL-20-001-EN-N Photos: see page 228 for copyright information PRINTED ON PROCESS CHLORINE-FREE RECYCLED PAPER (PCF) Contents 1 TEN YEARS ON: UNLOCKING THE CHARTER’S FULL POTENTIAL ..................................................................4 1.1. -

MUPDC-2021-Chapter56 28..39

Open Access Report The Critical Risk of Disinformation for Humanitarians – The Case of the MV Aquarius Sean Healy Head of Reflection and Analysis, Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre Amsterdam; [email protected] Victoria Russell Communications Adviser, Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre Amsterdam; [email protected] Abstract The search and rescue of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants on the Mediterranean has become a site of major political contestation in Europe, on the seas, in parliaments and government offices and in online public opinion. This article summarises one particular set of controversies, namely, false claims that the non-government organisations conducting such search and rescue operations are actively ‘colluding’ with people smugglers to ferry people into Europe. In spring and summer 2017, these claims of ‘collusion’ emerged from state agencies and from anti-immigration groups, became viral on social media platforms and rapidly moved into mainstream media coverage, criminal investigations by prosecutors and the speech and laws of politicians across the continent. These claims were in turn connected to far-right conspiracy theories about ‘flooding’ Europe with ‘invaders’. By looking at the experience of one particular ship, the MV Aquarius, run in partnership by MSF and SOS Méditerranée, the authors detail the risks that humanitarian organisations now face from such types of disinformation campaign. If humanitarian organisations do not prepare themselves against this risk, they will find themselves in a world turned upside-down, in which their efforts to help people in distress become evidence of criminal activity. Keywords: disinformation, conspiracy theory, search and rescue, refugees, Mediterranean, criminalisation, social media, far right, Médecins Sans Frontières, SOS Méditerranée Introduction homelands’ (statement by Defend Europe, quoted in Holthouse, 2017).