Hybridization of Cultivated Vitis Vinifera with Wild V.

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propagating California Wild Grape

Ratings of rooting systems (left) were best, good, and fair. Almost all types of vine wood yielded good root systems and resulted in vigorous plants. Propagating California wild grape James A. Robbins 0 David W. Burger Easy to start from cuttings, the vine is useful in landscape plantings California native plants are being used fluenced by such factors as date of collec- ing at that time, sap was flowing freely in increasingly in landscape and revegeta- tion, storage conditions, and type of cane the stems. The segments were transport- tion projects, but little information is wood. We conducted a study to investigate ed to Davis in an ice chest and stored in a available on how to propagate them. Cali- the effect of chemical pretreatment, cold room at 43°F (6°C) for three days. fornia wild grape, Vitis californica wood type, and rooting medium on the Before preparing and treating the cut- Benth., is one such plant that would be rooting of dormant hardwood cuttings of tings, we graded the stem wood into seven useful in the revegetation of steep slopes the California wild grape. classes according to stem diameter, stem and embankments. This vigorous, decidu- length, and type of wood (table 1). Al- ous, woody vine, which grows along though this grouping is artificial, these streams throughout the Coast Ranges, Rooting study categories correlated well with the posi- Central Valley, and Sierra Nevada foot- We collected propagation material in tion of wood on the original canes. Thin- hills, can cover large areas in a short mid-March 1985 from wild vines growing nest wood (grade A) would be associated time. -

Jéssica Karine Menon Dinâmica Temporal Da Antracnose

JÉSSICA KARINE MENON DINÂMICA TEMPORAL DA ANTRACNOSE EM ACESSOS DO BANCO DE GERMOPLASMA DE VIDEIRAS Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- graduação em Produção Vegetal do Centro de Ciências Agroveterinárias da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Produção Vegetal. Orientador: Dr. Amauri Bogo Coorientador: Dr. Ricardo Trezzi Casa LAGES, SANTA CATARINA 2016 M547d Menon, Jéssica Karine Dinâmica temporal da antracnose em acessos do banco de germoplasma de videiras / Jéssica Karine Menon. – Lages, 2016. 52 p.: il. Orientador: Amauri Bogo Coorientador: Ricardo Trezzi Casa Bibliografia: p. 45-52 Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, Centro de Ciências Agroveterinárias, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal, Lages, 2016. 1. Vitis spp. 2. Antracnose. 3. Germoplasma. 4. Melhoramento genético. I. Menon, Jéssica Karine. II. Bogo, Amauri. III. Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal. IV. Título CDD: 634.8 – 20.ed. Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Setorial do CAV/ UDESC JÉSSICA KARINE MENON DINÂMICA TEMPORAL DA ANTRACNOSE EM ACESSOS DO BANCO DE GERMOPLASMA DE VIDEIRAS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produção Vegetal do Centro de Ciências Agroveterinárias, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre. Banca Examinadora Lages, 22 de setembro de 2016. RESUMO MENON, Jéssica Karine. Dinâmica temporal da antracnose em acessos do banco de germoplasma de videiras. 2016. 52 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Produção Vegetal). Centro de Ciências Agroveterinárias, CAV. Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, UDESC. Lages, SC. A videira (Vitis spp. L.) é considerada uma das culturas mais importantes em todo o mundo, porém é uma atividade econômica recente no Brasil quando comparada aos tradicionais países produtores da Europa. -

A Note on Host Diversity of Criconemaspp

280 Pantnagar Journal of Research [Vol. 17(3), September-December, 2019] Short Communication A note on host diversity of Criconema spp. Y.S. RATHORE ICAR- Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur- 208 024 (U.P.) Key words: Criconema, host diversity, host range, Nematode Nematode species of the genus Criconema (Tylenchida: showed preference over monocots. Superrosids and Criconemitidae) are widely distributed and parasitize Superasterids were represented by a few host plants only. many plant species from very primitive orders to However, Magnoliids and Gymnosperms substantially advanced ones. They are migratory ectoparasites and feed contributed in the host range of this nematode species. on root tips or along more mature roots. Reports like Though Rosids revealed greater preference over Asterids, Rathore and Ali (2014) and Rathore (2017) reveal that the percent host families and orders were similar in number most nematode species prefer feeding on plants of certain as reflected by similar SAI values. The SAI value was taxonomic group (s). In the present study an attempt has slightly higher for monocots that indicate stronger affinity. been made to precisely trace the host plant affinity of The same was higher for gymnosperms (0.467) in twenty-five Criconema species feeding on diverse plant comparison to Magnolids (0.413) (Table 1). species. Host species of various Criconema species Perusal of taxonomic position of host species in Table 2 reported by Nemaplex (2018) and others in literature were revealed that 68 % of Criconema spp. were monophagous aligned with families and orders following the modern and strictly fed on one host species. Of these, 20 % from system of classification, i.e., APG IV system (2016). -

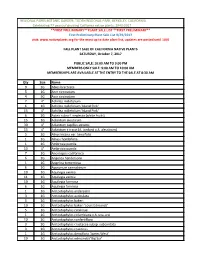

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Science Sixtyfourth64 National Conference a Platform for Progress

science sixtyfourth64 national conference a platform for progress 64th ASEV National Conference June 24–28, 2013 Portola Hotel and Monterey Conference Center Monterey, California USA TECHNICAL ABSTRACTS american society for enology and viticulture 2013 National Conference Technical Abstracts Oral Presentation Abstracts Wednesday, June 26 Enology — Flavor/Analysis ....................................................................59–62 Viticulture — Rootstocks .......................................................................63–66 Enology — Micro/Molecular Biology ....................................................67–70 Viticulture — Pests & Diseases ..............................................................71–74 Enology — Sensory/Sensory Impacts .....................................................75–78 Viticulture — Environmental Impacts ..................................................79–82 Enology — Flavor: Impact of Yeast and Bacteria ....................................83–86 Viticulture — General ...........................................................................87–90 Thursday, June 27 Enology — Wine Stability and Oxidation ..............................................91–93 Viticulture — Cultural Practices ............................................................94–96 Enology — Tannins (Part I) .................................................................97–100 Viticulture — Water Relations ...........................................................101–105 Enology — Tannins (Part II) ..............................................................106–108 -

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore EIR BIOLOGICAL TECHNICAL REPORT PROPOSED CARMAX AUTO SUPERSTORE PROJECT CITY OF OCEANSIDE, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EnviroApplications, Inc. 2831 Camino del Rio South, Suite 214 San Diego, California 92108 Contact: Megan Hill 619-291-3636 Prepared by: 4629 Cass Street, #192 San Diego, California 92109 Contact: Melissa Busby 858-334-9507 September 29, 2020 Revised March 23, 2021 Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1 Proposed Project Location .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Proposed Project Description ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2.0 – METHODS AND SURVEY LIMITATIONS ............................................ 8 2.1 Background Research .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 General Biological Resources Survey .................................................................. 8 2.3 Jurisdictional Delineation ...................................................................................... 9 2.3.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jurisdiction .................................................... 9 2.3.2 Regional Water Quality -

Gardening with California Desert Tortoises

GARDENING WITH CALIFORNIA DESERT TORTOISES (Gopherus agassizi) Theodore Payne Foundation for Wild Flowers & Native Plants 10459 Tuxford Street, Sun Valley, CA 91352 | 818 768-1802 | theodorepayne.org TP Desert Tortoise Mixture includes seeds for seven different native plant species, including many of those below. CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS NON-NATIVE PLANTS (A) = Annual wildflower: sow in fall Mulberry leaves Atriplex polycarpa (cattle spinach) Rose petals Baileya multiradiata (desert marigold) Geraniums Bouteloua curtipendula (side oats grama) Hibiscus flowers Castilleja exserta Dandelion leaves and flowers* Chilopsis linearis flowers (desert willow) Sow thistle* Eriogonum fasciculatum (CA buckwheat) Filaree* Lasthenia californica (goldfields) (A) Bermuda grass* Layia platyglossa (tidy tips) (A) St. Augustine grass* Layia glandulosa (white tidy tips) (A) Mediterranean grass* Malacothrix glabrata (desert dandelion) (A) Stinging nettle* Opuntia basilaris (beavertail cactus) Common mallow/cheeseweed* Chickweed* Phacelia distans (distant phacelia) (A) Phacelia tanacetifolia (lacy phacelia) (A) *These plants are invasive weeds in Salvia columbariae (chia) (A) California. Allow tortoises to forage on pre- Sphaeralcea ambigua (apricot mallow) existing material, but do not intentionally Stipa hymenoides (Indian rice grass) plant these. If desperate for these plants, Stipa speciosa (desert needlegrass) volunteer with a local non-profit (TPF, CNPS, Vitis girdiana (California desert grape) etc.) for the opportunity to help remove Xylorhiza tortifolia (Mojave aster) these plants from wild area TIPS Dandelion greens, as well as pre-cleaned cactus pads (nopales) and fruit (tunas) are available at certain grocery stores, such as Super King, Vallarta and Sunland Produce. once or twice a week in the form of cuttlebone (with hard backing removed) or boiled, ground eggshell. Mimic a rainstorm every couple of weeks, allowing puddles to form near your tortoise. -

Plant List for Lawn Removal

VERY LOW WATER USE PLANTS Trees * Aesculus californica California buckeye * Cercis occidentalis western redbud * Fremontodendron spp. flannel bush * Pinus abiniana foothill pine * Quercus agrifolia coast live oak * Quercus wislizeni interior live oak Shrubs * Adenostoma fasciciulatum chamise * Arctostaphylos spp. manzanita * Artemesia californica California sagebrush * Ceanothus spp wild lilac * Cercocarpus betuloides mountain mahogany * Amelanchier alnifolia service berry * Dendromecon spp. bush poppy * Heteromeles arbutifolia toyon * Mahonia nevinii Nevin mahonia Perennials * Artemesia tridentata big sagebrush Ballota pseudodictamnus Grecian horehouond * Monardella villosa coyote mint * Nasella needlegrass Penstemon centranthifolius "Scarlet * scarlet bugler penstemon Bugler" * Romneay coulteri Matilija poppy * Salvia apiana white sage * Sisyrinchium bellum blue-eyed grass * Trichostema lanatum woolly blue curls Edibles Olea europaea olive Opunita spp. prickly pear/cholla Cactus and Succulents Cephalocereus spp. old man cactus Echinocactus barrel cactus Graptopetalum spp graptopetalum Bunch Grasses * Bouteloua curtipendula sideoats gramma * Festuca idahoensis Idaho fescue * Leymus condensatus 'Canyon Prince' giant wild rye Bulbs Amaryllis belladona naked lady * Brodiaea spp. brodiaea Colchicum agrippium autumn crocus Muscari macrocarpum grape hyacinth Narcissus spp. daffodil Scilla hughii bluebell Scilla peruviana Peruvian lily Annuals Dimorphotheca spp. African daisy * Eschscholzia californica California poppy Mirabilis jalapa four -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

California Wetlands

VOL. 46, NO.2 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY California Wetlands 1 California Native Plant Society CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5130 Phone: (916) 447-2677 • Fax: (916) 447-2727 FREMONTIA www.cnps.org • [email protected] VOL. 46, NO. 2, November 2018 Memberships Copyright © 2018 Members receive many benefits, including a subscription toFremontia California Native Plant Society and the CNPS Bulletin. Look for more on inside back cover. ISSN 0092-1793 (print) Mariposa Lily.............................$1,500 Family..............................................$75 ISSN 2572-6870 (online) Benefactor....................................$600 International or library...................$75 Patron............................................$300 Individual................................$45 Gordon Leppig, Editor Plant lover.....................................$100 Student/retired..........................$25 Michael Kauffmann, Editor & Designer Corporate/Organizational 10+ Employees.........................$2,500 4-6 Employees..............................$500 7-10 Employees.........................$1,000 1-3 Employees............................$150 Staff & Contractors Dan Gluesenkamp: Executive Director Elizabeth Kubey: Outreach Coordinator Our mission is to conserve California’s Alfredo Arredondo: Legislative Analyst Sydney Magner: Asst. Vegetation Ecologist native plants and their natural habitats, Christopher Brown: Membership & Sales David Magney: Rare Plant Program Manager and increase understanding, -

Native Plants

CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS A Planting Guide for Ventura County Your Garden Matters California native plants are a great landscaping choice for your home garden. Not only are they beautiful, they offer important benefits. Native gardens support the food webs, watersheds, and ecosystems upon which we all depend. The simple act of replacing your lawn with California native plants is a powerful way to make a difference. Save water Reduce maintenance Cut pesticide use Support local ecology Help the birds and butterflies! Tips for Success Once established, a California native garden is easier and Think Like a Watershed less expensive to maintain than traditional landscapes. Use your landscape to capture water and minimize run-off. Set your garden up for success with a few important tips - some might surprise you. • Contour your landscape with berms, swales, and dry creek beds. • Use permeable surfaces wherever possible to allow Plant with Care water to infiltrate into the soil below. 1. Choose the right time. Plant fall through early spring to • Direct water from downspouts and driveways to your take advantage of cooler temperatures and rainfall. water capture designs and other permeable area to help keep water on site and benefit your plants. 2. Plant with care. Dig a hole 1.5x as deep as the plant and 2x as wide, leaving the crown a half inch higher than the ground. Create a circular berm around the edge of the Set Your Foundation hole to form a water basin. 3. Room to breathe. Make sure mulch doesn’t touch the Evergreen plants and hardscapes provide structure to keep plant’s crown or cover irrigation sources. -

Nr 222 Native Tree, Shrub, & Herbaceous Plant

NR 222 NATIVE TREE, SHRUB, & HERBACEOUS PLANT IDENTIFICATION BY RONALD L. ALVES FALL 2014 NR 222 by Ronald L. Alves Note to Students NOTE TO STUDENTS: THIS DOCUMENT IS INCOMPLETE WITH OMISSIONS, ERRORS, AND OTHER ITEMS OF INCOMPETANCY. AS YOU MAKE USE OF IT NOTE THESE TRANSGRESSIONS SO THAT THEY MAY BE CORRECTED AND YOU WILL RECEIVE A CLEAN COPY BY THE END OF TIME OR THE SEMESTER, WHICHEVER COMES FIRST!! THANKING YOU FOR ANY ASSISTANCE THAT YOU MAY GIVE, RON ALVES. Introduction This manual was initially created by Harold Whaley an MJC Agriculture and Natural Resources instruction from 1964 – 1992. The manual was designed as a resource for a native tree and shrub identification course, Natural Resources 222 that was one of the required courses for all forestry and natural resource majors at the college. The course and the supporting manual were aimed almost exclusively for forestry and related majors. In addition to NR 222 being taught by professor Whaley, it has also been taught by Homer Bowen (MJC 19xx -), Marlies Boyd (MJC 199X – present), Richard Nimphius (MJC 1980 – 2006) and currently Ron Alves (MJC 1974 – 2004). Each instructor put their own particular emphasis and style on the course but it was always oriented toward forestry students until 2006. The lack of forestry majors as a result of the Agriculture Department not having a full time forestry instructor to recruit students and articulate with industry has resulted in a transformation of the NR 222 course. The clientele not only includes forestry major, but also landscape designers, environmental horticulture majors, nursery people, environmental science majors, and people interested in transforming their home and business landscapes to a more natural venue.