Balancing the Commons in Switzerland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Roadbook TVA 2021 ANG

HIKING TOUR OF THE VAL D’ANNIVIERS TOURVALDANNIVIERS.CH NGLISH e WOWWeLCOMe. ! REaDY TO MaKE MEMORIES? Hé! Let's stay in touch: Find us on social media to discover, revisit and share all the things that make our region so exciting. BeTWeeN TRANQUILLITY aND WONDER - THE PERFECT BALANCE - Walk at your own pace, follow the signs, and picnic when and where ever you want. Sleep somewhere different every night and marvel at the extraordinary scenery of this region in Central Valais. The traditional circuit leads you from Sierre via, in order, Chandolin/ St-Luc, Zinal, Grimentz and Vercorin and back to Sierre. Each day’s walk is around 5 hours. Optional visit on the last day: discover the Vallon de Réchy, a natural jewel and highlight. Each stage can be done separately if you wish to shorten your stay. It is also interesting to spend two nights in each resort to take advantage of what is on offer locally. 4 HIKING TOUR OF THe VAL D’ANNIVIeRS - VALID FROM JUNE 19 TO OCTOBER 2, 2021 * - THe TRAIL This description was produced for A symbol indicates the route along the whole a standard 5 night tour, we suggest length of the trail. It can be done without a you adapt it to suit your own programme. guide. So you are free to go at your own pace and choose your own picnic spots and stop- • From 2 nights in a hotel, gîte or ping points to admire the panoramas and mountain hut: Sierre, St-Luc/ landscapes which reveal themselves along Chandolin, Zinal, Grimentz and the way. -

Rhin-Reuss-Rhône

Guide vers le chemin de Saint-Jacques RHIN-REUSS-RHÔNE Parcourir le patrimoine sacré du couvent de Disentis à l’abbaye de Saint-Maurice Guide abrégé Chemin Rhin-Reuss-Rhône Une voie de liaison au chemin de Saint-Jacques Un trésor sacré dans les Alpes du couvent de Disentis à l’abbaye de Saint-Maurice Au cours de notre pèlerinage des « pays d’en-bas » voulaient plaire Infos: www.viajacobi4.ch de deux semaines, de Disentis à à Dieu par leur travail, les catho- Saint-Maurice, l’ennui ne pouvait liques des montagnes, à coup de Konstanz naître que de la religion – catho- prières et de dons, construisaient lique. Mais loin de là ! Cela n‘a pas de nouvelles églises, chapelles et toujours été le cas ! Laissez-vous autels. Bien que nous rencon- Rorschach entraîner dans les intrigues, les trons des vallées économiquement assassinats et meurtres, l’espérance faibles, nous bénéficions d’un riche et la foi que les gens de ces mon- patrimoinee sacré, dont les bâti- Einsiedeln tagnes trouvaient dans la religion, ments sont - à la stupéfaction des il y a encore deux générations. étrangers - généralement ouverts En plus des traces des saints pèler- pendant la journée. Profitons de Disentis ins, nous découvrons à chaque éta- ces chapelles comme de petits pe des beautés de l’art sacré et des musées. Durant les premier jours, curiosités, la foi en Dieu ayant do- nous rencontrons le baroque alpin Saint- Brig miné la vie quotidienne. Où ailleurs le plus exubérant. Progressivement Maurice Sion ViaJacobi no 4 Genève Chemin liaison peut-on trouver des parois d’osse- remplacé, au fur et à mesure de Rhin-Reuss-Rhône ments aux dizaines de milliers de notre avance et de la baisse d’alti- ViaFrancigena crânes, un cimetière de célibataires, tude, par un austère gothique des évêques qui jouaient leur âme tardif, cà et là interrompu par la au diable, des plaquettes en bois, pierre du style roman. -

Mirs E Microcosmos Ella Val Da Schluein

8SGLINDESDI, ILS 19 DA OCTOBER 2015 URSELVA La gruppa ch’ei separticipada al cuors da construir mirs schetgs ha empriu da dosar las forzas. Ina part dalla giuventetgna che ha prestau lavur cumina: Davontier las sadialas culla crappa da Schluein ch’ei FOTOS A. BELLI vegnida rutta, manizzada e mulada a colur. Mirs e microcosmos ella Val da Schluein La populaziun ha mussau interess pil Gi da Platta Pussenta (anr/abc) Sonda ha la populaziun da caglias. Aposta per saver luvrar efficient Dar peda als Schluein e dallas vischnauncas vischi entuorn il liung mir schetg surcarschiu ha animals pigns da scappar nontas giu caschun da separticipar ad vevan ils luvrers communals runcau col Jürg Paul Müller, il cussegliader ed accumpi in suentermiezgi d’informaziun ella Val lers, fraissens e spinatscha. gnader ecologic dalla fundaziun Platta Pus da Schluein. El center ei buca la situa senta, ha informau ils presents sin ina runda ziun dalla val stada, mobein singuls Mantener mirs schetgs fa senn entuorn ils mirs schetgs. Sch’ins reconstrue beins culturals ch’ei dat a Schluein. La Il Gi da Platta Pussenta ha giu liug per la schi e mantegni mirs schetgs seigi ei impur fundaziun Platta Pussenta ha organisau quarta gada. Uonn ein scazis ella cuntrada tont da buca disfar ils biotops da fauna e flo in dieta tier la tematica dils mirs schetgs culturala da Schluein stai el center. Fina ra. Mirs schetgs porschan spazi ad utschals, e dalla crappa. L’aura ei stada malsegira, mira eis ei stau da mussar quels e render at reptils ed insects, cheu san els sezuppar, cuar, l’entira jamna ei stada plitost freida e ble tent a lur valur. -

17A MAESTRIA PAC Faido Torre

2019 17 a MAESTRIA PAC Leventinese – Bleniese Faido Torre 8 linee elettroniche 8 linee elettroniche 6 – 8.12.2019 Fabbrica di sistemi Fabbrica di rubinetteria d’espansione, sicurezza e sistemi sanitari / e taratura riscaldamento e gas Fabbrica di circolatori e pompe Fabbrica di pompe fecali/drenaggio e sollevamento d’acqua Bärtschi SA Via Baragge 1 c - 6512 Giubiasco Tel. 091 857 73 27 - Fax 091 857 63 78 Fabbrica di corpi riscaldanti e www.impiantistica.ch Fabbrica di bollitori, cavo riscaldante, impianti di ventilazione e-mail: [email protected] caldaie, serbatoi per nafta, controllata impianti solari e termopompe Fabbrica di scambiatori di calore Fabbrica di diffusori per l’immissione a piastre, saldobrasati e a e l’aspirazione dell’aria, clappe fascio tubiero tagliafuoco e regolatori di portata DISPOSIZIONI GENERALI Organizzazione: Tiratori Aria Compressa Blenio (TACB) – Torre Carabinieri Faidesi, Sezione AC – Faido Poligoni: Torre vedi piantina 8 linee elettroniche Faido vedi piantina 8 linee elettroniche Date e Orari: 29.11.19 aperto solo se richiesto 30.11.19 dalle ore 14.00 – 19.00 1.12.19 6.12.19 dalle 20.00 alle 22.00 7.12.19 dalle 14.00 alle 19.00 8.12.19 dalle 14.00 alle 18.00 Un invito ai tiratori ticinesi e del Moesano, ma anche ad amici provenienti da fuori cantone, a voler sfruttare la possibilità di fissare un appuntamento, per telefono ai numeri sotto indicati. L’appuntamento nei giorni 29–30–01 è possibile solo negli orari indicati. Appuntamenti: Contattare i numeri telefonici sotto indicati. Iscrizioni: Mediante formulari ufficiali, entro il 19.11.2019 Maestria – TORRE: Barbara Solari Via Ponte vecchio 3 6742 Pollegio 076 399 75 16 [email protected] Maestria – FAIDO: Alidi Davide Via Mairengo 29 6763 Mairengo 079 543 78 75 [email protected] Formulari e www.tacb.ch piano di tiro: www.carabinierifaidesi.ch Regole di tiro: Fanno stato il regolamento ISSF e le regole per il tiro sportivo (RTSp) della FST. -

2019-04-26 La Quotidiana.Pdf

SURSELVA VENDERDI, ILS 26 DA AVRIGL 2019 5 Conceder daners per planisar La votaziun per il credit en favur dil lag Salischinas vala era sco indicatur d’acceptanza dil project DAD ANDREAS CADONAU / ANR munal davart las finamiras economicas dil project che duei regenerar 20 000 pernot- Il suveran dalla vischnaunca da taziuns supplementaras ella regiun e quei Sumvitg ei envidada da decider igl duront diesch meins da menaschi cun in emprem da matg a caschun dad ina ra- focus sin la sesiun da stad. Ed ils projecta- dunonza communala davart in credit ders quentan cun 25 novas plazzas da la- da planisaziun da 250 000 francs en fa- vur. Caduff ei per t scharts dalla vasta di- vur dil project lag Salischinas. Per ils mensiun dil project, ei denton perschua- promoturs dil projet, l’Uniun lag Sali- dius che quella dimensiun seigi necessaria schinas, ina decisiun da valur dubla. per contonscher las finamiras. Ed il presi- Il president dall’Uniun lag Salischinas, dent dall’Uniun lag Salischinas ei per- Rino Caduff, ha concediu ch’il projet lag tscharts ch’il project ha da surmuntar aunc Salischinas ei periclitaus acut, havess la enqual obstachel era cun il clar gie dalla radunonza communala dalla vischnaun- radunonza communala dalla vischnaunca ca da Sumvitg da renviar igl emprem da da Sumvitg. Anflar ina buna sligiaziun per matg la damonda dil credit da planisa- l’agricultura indigena che piarda ina puli- ziun da 250 000 francs. El ei denton da ta surfa tscha terren agricol entras il lag ei buna speronza che quei succedi buc. -

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland Dr. Liliana Schönberger Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Light pollution ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 The origins of artificial light ................................................................................ 4 1.1.2 Can light be “pollution”? ...................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Impacts of light pollution on nature and human health .................................... 6 1.1.4 The efforts to minimize light pollution ............................................................... 7 1.2 Hypotheses .................................................................................................................. 8 2 Methods ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Literature review ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Spatial analyses ........................................................................................................ 10 3 Results ....................................................................................................................11 -

Orari Sante Messe Vicariato Delle Tre Valli

Orari Sante Messe Vicariato delle Tre Valli RIVIERA Biasca Chiesa di S. Carlo sa – ore 17.30 do – ore 08.00/10.00/19.30 Claro Chiesa dei Ss. Rocco e Sebastiano do – ore 10.30 Chiesa dei Ss. Nazaro e Celso sa – ore 17.30 (da novembre a marzo) sa – ore 19.30 (da aprile a ottobre) Cresciano Chiesa di S. Vincenzo do – ore 09.15 Gnosca Chiesa di S. Pietro do – ore 09.15 Iragna Chiesa dei Ss. Martiri Maccabei do – ore 17.30 (da luglio a ottobre) do – ore 09.00 (da marzo a giugno) Lodrino Chiesa di S. Ambrogio sa – ore 18.30 do – ore 10.30 Moleno Chiesa di S. Vittore sa – ore 17.30 (IV sabato del mese) Osogna Chiesa dei Ss. Gratiniano e Felino do – ore 10.30 Preonzo Chiesa dei Ss. Simone e Giuda sa – ore 17.30 (tranne IV sabato del mese) Prosito Chiesa dei Ss. Gervasio e Protasio do – ore 09.00 (da luglio a ottobre) do – ore 17.30 (da marzo a giugno) LEVENTINA Airolo Chiesa di S. Nazaro e Celso do – ore 10.15 Nante sa – ore 17.30 Madrano sa – ore 18.30 Villa Bedretto do – ore 9.00 Anzonico Chiesa di S. Giovanni Battista Consultare il sito del Comune di Faido 1/3 Bodio Chiesa di S. Stefano do – ore 10.30 Calonico Chiesa di S. Martino Consultare il sito del Comune di Faido Calpiogna Chiesa di S. Atanasio Consultare il sito del Comune di Faido Campello Chiesa di S. Margherita Consultare il sito del Comune di Faido Cavagnago Chiesa di S. -

Alpine Common Property Institutions Under Change

Alpine Common Property Institutions under Change: Conditions for Successful and Unsuccessful Collective Action of Alpine Farmers in the Canton Graubünden of Switzerland Gabriela Landolt, Tobias Haller Abstract: The goal to protect and sustainably manage alpine summer pastures is stated in the Swiss state law since 1996 and direct subsidy payments from the state for summer pasturing have been bound to sustainability criteria since 2000 reflecting the increasing value of the alpine cultural landscape as a public good. However, the provision of the public good remains in the hands of the local farmers and their local common pool resource (CPR) institutions to manage the alpine pastures and those institutions increasingly struggle with upholding their institutional arrangements particularly regarding the communal work, called Gemeinwerk, necessary to maintain the pastures. This paper examines two case studies of local CPR institutions to manage alpine pastures in the canton Graubünden of Switzerland manifesting different institutional developments in the light of changing conditions. Explanations for the unequal reactions to change and their impacts on the provision of the CPR are provided by focusing on relative prices, bargaining power and ideology as drivers of institutional change often neglected within common property research. Keywords summer pasture management, institutional change, multi-level governance Gabriela Landolt is a doctoral student and Tobias Haller is an associate professor at the Institute for Social Anthropology, University of Bern, Switzerland. Main research interests are the analysis of institutional change in the context of common pool resource management under special consideration of power relations and ideology. G. Landolt: Muesmattstr. 4, 3000 Bern 9 / [email protected] T. -

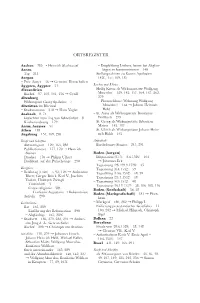

Ortsregister

OrtsregIster Aachen—285 → heinrich slachtscaef – empfehlung luthers, besser bei altgläu- Aarau bigen zu kommunizieren—140 – tag—211 – stellungnahmen zu Bucers apologien— Aargau 142f., 157, 169, 187 – Freie Ämter—36 → gemeine herrschaften Ägypten, Ägypter—51 Kirchen und Klöster Alexandrien – heilig Kreuz als Wirkungsstätte Wolfgang – Bischof—97, 102, 141, 156 → cyrill Musculus’—129, 142, 157, 164, 187, 262, Altenburg 279 – Wirkungsort georg spalatins—7 – Pfarrzechhaus (Wohnung Wolfgang Altstätten im rheintal Musculus’)—164 → Johann heinrich – stadtammann—218 → hans vogler held Ansbach—8, 74 – st. anna als Wirkungsstätte Bonifatius – gutachten zum tag von schweinfurt—8 Wolfharts—279 – Kirchenordnung—179 – st. georg als Wirkungsstätte sebastian Assur, Assyrer—51 Maiers—143, 187 Athen—158 – st. ulrich als Wirkungsstätte Johann hein- Augsburg—157, 169, 290 rich helds—163 Briefe und Schriften Aufenthalt – abfassungsort—129, 163, 288 – Bartholomeo Fonzios—243, 291 – Publikationsort—157, 170 → heinrich steiner Baden (Aargau) – Drucker—170 → Philipp ulhart – Disputation (21.5. – 8.6.1526)—101 – Drohbrief auf der Perlachstiege—290 → Johannes eck – tagsatzung (28./29.9.1528)—35 Ereignisse – tagsatzung (8.4.1532)—59 – reichstag (1530)—5, 92, 126 → ambrosius – tagsatzung (10.6.1532)—48, 59 Blarer, gregor Brück, Karl v., Joachim – tagsatzung (23.7.1532)—48 vadian, huldrych zwingli – tagsatzung (4.9.1532)—48 – türkenhilfe—5 – tagsatzung (16.12.1532)—38, 106–108, 116 – causa religionis—38f. Baden (Grafschaft)—36, 58 – confessio augustana Bekenntnisse → Baden (Markgrafschaft)—181 → Pforz- – aufruhr—290 heim Institutionen – Markgraf—180, 282 → Philipp I. – rat—165, 289 – exilierung protestantischer geistlicher—11, – einführung der reformation—290 180, 282 → Michael hilspach, christoph – altgläubige—165, 289f. sigel – stadtarzt—186, 279, 288, 291 → ambro- Balkan—22 sius Jung d. -

Inhaltsübersicht

Inhaltsübersicht Erstes Buch. Das Interregnum der langen Tagsatzung 1813—1815. S. 1-402 I. Der Durchzug der Verbündeten 1813/1814 S. 3— 62 Lage im Beginn des Jahres 1813. Verschärfung der Zen sur und Kontinentalsperre 3. — Erhöhung des Rekrutentributs an Napoleon 4. — Mülinens Projekt einer Bewaffnung 5. — Ordentliche Tagsatzung in Zürich 6. — Außerordentliches Trup- , penbegehren Napoleons 7. — Landammann Reinhard 8. — Räumung des Tessin 9. — Außerordentliche Tagsatzung 10. — Verhinderung eines größeren Truppenaufgebots durch Napo- leon. Neutralitätserklärung 11. — Anerkennung der Neutralität durch Napoleon 12. — Kriegsplan der Verbündeten. Capo d'Jstria und Lebzeltern in Zürich 13. — Motive der schweiz. Neutralität 14. — Reaktionshoffnungen in Bern 15. — Besorg nisse der Demokraten 16. — Unzulänglichkeit der Grenzbesetzung 17. Unentschlossenheit Reinhards 18. — Vorrücken der Haupt armee gegen die Schweiz 19. — Befehle Schwarzenbergs für den Rheinübergang 21. — Kaiser Alexander, Laharpe, Jomini, Fräulein Mazelet21/22. — Reding und Escher in Frankfurt 22/23. — Anscheinende Anerkennung der Neutralität, Sistierung des Ein- Marsches 23. — Metternich, Schwarzenberg, Radetzky gegen die Neutralität 24. — Verbot der Neutralitätsproklamation durch die ->Berner Regierung. Sendung Zeerleders und Mills 26. — Lan desverrat der Berner Unbedingten 27. — Graf Johann von Salis-Soglio 28. — Das Waldshuter Komitee in Freiburg 29. — Entschluß des Kaisers Franz zum Einmarsch 31. — Metternich und die Schweizer Gesandten 32i — Kapitulation von Lörrach ' 33. — Rückzug der eidg. Armee 34. — Auflösung der eidg. Ar- mee 35. — Rheinübergang der Österreicher. Bubna in Bern 36. — Die Österreicher in Neuenburg und Biel 37. — In Schaff- .Hausen und Zürich 38. — Vormarsch der Hauptarmee nach Frankreich 39. — Bubna in Lausanne 40. — Genf unter fran zösischer Herrschaft 41. — Gärung in Genf 42. — Bubna in Genf. e Provisorische Regierung 44. -

Castelli Di Bellinzona

Trenino Artù -design.net Key Escape Room Torre Nera La Torre Nera di Castelgrande vi aspetta per vivere una entusiasmante espe- rienza e un fantastico viaggio nel tempo! Codici, indizi e oggetti misteriosi che vi daranno la libertà! Una Room ambientata in una location suggestiva, circondati da 700 anni di storia! Prenotate subito la vostra avventura medievale su www.blockati.ch Escape Room Torre Nera C Im Turm von Castelgrande auch “Torre Nera” genannt, kannst du ein aufre- gendes Erlebnis und eine unglaubliche Zeitreise erleben! Codes, Hinweise M und mysteriöse Objekte entschlüsseln, die dir die Freiheit geben! Ein Raum in Y einer anziehender Lage, umgeben von 700 Jahren Geschichte! CM Buchen Sie jetzt Ihr mittelalterliches Abenteuer auf www.blockati.ch MY Escape Room Tour Noire CY La Tour Noire de Castelgrande, vous attends pour vivre une expérience pas- CMY sionnante et un voyage fantastique dans le temps ! Des codes, des indices et des objets mystérieux vous donneront la liberté! Une salle dans un lieu Preise / Prix / Prices Orari / Fahrplan / Horaire / Timetable K évocateur, entouré de 700 ans d’histoire ! Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Réservez votre aventure médiévale dès maintenant sur www.blockati.ch Trenino Artù aprile-novembre Do – Ve / So – Fr / Di – Ve / Su – Fr 10.00 / 11.20 / 13.30 / 15.00 / 16.30 Adulti 12.– Piazza Governo Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Escape Room Black Tower Sa 11.20 / 13.30 The Black Tower of Castelgrande, to live an exciting experience and a fan- Ridotti Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure tastic journey through time! Codes, clues and mysterious objects that will Senior (+65), studenti e ragazzi 6 – 16 anni 10.– Sa 15.00 / 16.30 give you freedom! A Room set in an evocative location, surrounded by 700 a Castelgrande, years of history! Gruppi (min. -

Article (Published Version)

Article Gold mineralisation in the Surselva region, Canton Grisons, Switzerland JAFFE, Felice Abstract The Tavetsch Zwischenmassif and neighbouring Gotthard Massif in the Surselva region host 18 gold-bearing sulphide occurrences which have been investigated for the present study. In the Surselva region, the main rock constituting the Tavetsch Zwischenmassif (TZM) is a polymetamorphic sericite schist, which is accompanied by subordinate muscovite-sericite gneiss. The entire tectonic unit is affected by a strong vertical schistosity, which parallels its NE-SW elongation. The main ore minerals in these gold occurrences are pyrite, pyrrhotite and arsenopyrite. The mineralisation occurs in millimetric stringers and veinlets, everywhere concordant with the schistosity. Native gold is present as small particles measuring 2–50 μm, and generally associated with pyrite. Average grades are variable, but approximate 4–7 g/t Au, with several occurrences attaining 14 g/t Au. Silver contents of the gold are on the order of 20 wt%. A “bonanza” occurrence consists of a quartz vein coated by 1.4 kg of native gold. The origin of the gold is unknown. On the assumption that the sericite schists are derived from original felsic [...] Reference JAFFE, Felice. Gold mineralisation in the Surselva region, Canton Grisons, Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 2010, vol. 103, no. 3, p. 495-502 DOI : 10.1007/s00015-010-0031-3 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:90702 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1