Differential Geometry, Part I: Calculus on Euclidean Spaces Jay Havaldar from Wikipedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

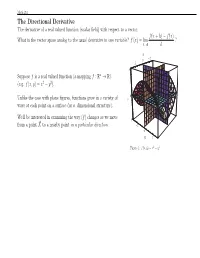

The Directional Derivative the Derivative of a Real Valued Function (Scalar field) with Respect to a Vector

Math 253 The Directional Derivative The derivative of a real valued function (scalar field) with respect to a vector. f(x + h) f(x) What is the vector space analog to the usual derivative in one variable? f 0(x) = lim − ? h 0 h ! x -2 0 2 5 Suppose f is a real valued function (a mapping f : Rn R). ! (e.g. f(x; y) = x2 y2). − 0 Unlike the case with plane figures, functions grow in a variety of z ways at each point on a surface (or n{dimensional structure). We'll be interested in examining the way (f) changes as we move -5 from a point X~ to a nearby point in a particular direction. -2 0 y 2 Figure 1: f(x; y) = x2 y2 − The Directional Derivative x -2 0 2 5 We'll be interested in examining the way (f) changes as we move ~ in a particular direction 0 from a point X to a nearby point . z -5 -2 0 y 2 Figure 2: f(x; y) = x2 y2 − y If we give the direction by using a second vector, say ~u, then for →u X→ + h any real number h, the vector X~ + h~u represents a change in X→ position from X~ along a line through X~ parallel to ~u. →u →u h x Figure 3: Change in position along line parallel to ~u The Directional Derivative x -2 0 2 5 We'll be interested in examining the way (f) changes as we move ~ in a particular direction 0 from a point X to a nearby point . -

A Comparison of Differential Calculus and Differential Geometry in Two

1 A Two-Dimensional Comparison of Differential Calculus and Differential Geometry Andrew Grossfield, Ph.D Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology Abstract and Introduction: Plane geometry is mainly the study of the properties of polygons and circles. Differential geometry is the study of curves that can be locally approximated by straight line segments. Differential calculus is the study of functions. These functions of calculus can be viewed as single-valued branches of curves in a coordinate system where the horizontal variable controls the vertical variable. In both studies the derivative multiplies incremental changes in the horizontal variable to yield incremental changes in the vertical variable and both studies possess the same rules of differentiation and integration. It seems that the two studies should be identical, that is, isomorphic. And, yet, students should be aware of important differences. In differential geometry, the horizontal and vertical units have the same dimensional units. In differential calculus the horizontal and vertical units are usually different, e.g., height vs. time. There are differences in the two studies with respect to the distance between points. In differential geometry, the Pythagorean slant distance formula prevails, while in the 2- dimensional plane of differential calculus there is no concept of slant distance. The derivative has a different meaning in each of the two subjects. In differential geometry, the slope of the tangent line determines the direction of the tangent line; that is, the angle with the horizontal axis. In differential calculus, there is no concept of direction; instead, the derivative describes a rate of change. In differential geometry the line described by the equation y = x subtends an angle, α, of 45° with the horizontal, but in calculus the linear relation, h = t, bears no concept of direction. -

Notes for Math 136: Review of Calculus

Notes for Math 136: Review of Calculus Gyu Eun Lee These notes were written for my personal use for teaching purposes for the course Math 136 running in the Spring of 2016 at UCLA. They are also intended for use as a general calculus reference for this course. In these notes we will briefly review the results of the calculus of several variables most frequently used in partial differential equations. The selection of topics is inspired by the list of topics given by Strauss at the end of section 1.1, but we will not cover everything. Certain topics are covered in the Appendix to the textbook, and we will not deal with them here. The results of single-variable calculus are assumed to be familiar. Practicality, not rigor, is the aim. This document will be updated throughout the quarter as we encounter material involving additional topics. We will focus on functions of two real variables, u = u(x;t). Most definitions and results listed will have generalizations to higher numbers of variables, and we hope the generalizations will be reasonably straightforward to the reader if they become necessary. Occasionally (notably for the chain rule in its many forms) it will be convenient to work with functions of an arbitrary number of variables. We will be rather loose about the issues of differentiability and integrability: unless otherwise stated, we will assume all derivatives and integrals exist, and if we require it we will assume derivatives are continuous up to the required order. (This is also generally the assumption in Strauss.) 1 Differential calculus of several variables 1.1 Partial derivatives Given a scalar function u = u(x;t) of two variables, we may hold one of the variables constant and regard it as a function of one variable only: vx(t) = u(x;t) = wt(x): Then the partial derivatives of u with respect of x and with respect to t are defined as the familiar derivatives from single variable calculus: ¶u dv ¶u dw = x ; = t : ¶t dt ¶x dx c 2016, Gyu Eun Lee. -

Tensor Calculus and Differential Geometry

Course Notes Tensor Calculus and Differential Geometry 2WAH0 Luc Florack March 10, 2021 Cover illustration: papyrus fragment from Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, Book II [8]. Contents Preface iii Notation 1 1 Prerequisites from Linear Algebra 3 2 Tensor Calculus 7 2.1 Vector Spaces and Bases . .7 2.2 Dual Vector Spaces and Dual Bases . .8 2.3 The Kronecker Tensor . 10 2.4 Inner Products . 11 2.5 Reciprocal Bases . 14 2.6 Bases, Dual Bases, Reciprocal Bases: Mutual Relations . 16 2.7 Examples of Vectors and Covectors . 17 2.8 Tensors . 18 2.8.1 Tensors in all Generality . 18 2.8.2 Tensors Subject to Symmetries . 22 2.8.3 Symmetry and Antisymmetry Preserving Product Operators . 24 2.8.4 Vector Spaces with an Oriented Volume . 31 2.8.5 Tensors on an Inner Product Space . 34 2.8.6 Tensor Transformations . 36 2.8.6.1 “Absolute Tensors” . 37 CONTENTS i 2.8.6.2 “Relative Tensors” . 38 2.8.6.3 “Pseudo Tensors” . 41 2.8.7 Contractions . 43 2.9 The Hodge Star Operator . 43 3 Differential Geometry 47 3.1 Euclidean Space: Cartesian and Curvilinear Coordinates . 47 3.2 Differentiable Manifolds . 48 3.3 Tangent Vectors . 49 3.4 Tangent and Cotangent Bundle . 50 3.5 Exterior Derivative . 51 3.6 Affine Connection . 52 3.7 Lie Derivative . 55 3.8 Torsion . 55 3.9 Levi-Civita Connection . 56 3.10 Geodesics . 57 3.11 Curvature . 58 3.12 Push-Forward and Pull-Back . 59 3.13 Examples . 60 3.13.1 Polar Coordinates in the Euclidean Plane . -

Matrix Calculus

Appendix D Matrix Calculus From too much study, and from extreme passion, cometh madnesse. Isaac Newton [205, §5] − D.1 Gradient, Directional derivative, Taylor series D.1.1 Gradients Gradient of a differentiable real function f(x) : RK R with respect to its vector argument is defined uniquely in terms of partial derivatives→ ∂f(x) ∂x1 ∂f(x) , ∂x2 RK f(x) . (2053) ∇ . ∈ . ∂f(x) ∂xK while the second-order gradient of the twice differentiable real function with respect to its vector argument is traditionally called the Hessian; 2 2 2 ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) 2 ∂x1 ∂x1∂x2 ··· ∂x1∂xK 2 2 2 ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) 2 2 K f(x) , ∂x2∂x1 ∂x2 ··· ∂x2∂xK S (2054) ∇ . ∈ . .. 2 2 2 ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) ∂ f(x) 2 ∂xK ∂x1 ∂xK ∂x2 ∂x ··· K interpreted ∂f(x) ∂f(x) 2 ∂ ∂ 2 ∂ f(x) ∂x1 ∂x2 ∂ f(x) = = = (2055) ∂x1∂x2 ³∂x2 ´ ³∂x1 ´ ∂x2∂x1 Dattorro, Convex Optimization Euclidean Distance Geometry, Mεβoo, 2005, v2020.02.29. 599 600 APPENDIX D. MATRIX CALCULUS The gradient of vector-valued function v(x) : R RN on real domain is a row vector → v(x) , ∂v1(x) ∂v2(x) ∂vN (x) RN (2056) ∇ ∂x ∂x ··· ∂x ∈ h i while the second-order gradient is 2 2 2 2 , ∂ v1(x) ∂ v2(x) ∂ vN (x) RN v(x) 2 2 2 (2057) ∇ ∂x ∂x ··· ∂x ∈ h i Gradient of vector-valued function h(x) : RK RN on vector domain is → ∂h1(x) ∂h2(x) ∂hN (x) ∂x1 ∂x1 ··· ∂x1 ∂h1(x) ∂h2(x) ∂hN (x) h(x) , ∂x2 ∂x2 ··· ∂x2 ∇ . -

Riemann's Contribution to Differential Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematics 9 (1982) l-18 RIEMANN'S CONTRIBUTION TO DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY BY ESTHER PORTNOY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, URBANA, IL 61801 SUMMARIES In order to make a reasonable assessment of the significance of Riemann's role in the history of dif- ferential geometry, not unduly influenced by his rep- utation as a great mathematician, we must examine the contents of his geometric writings and consider the response of other mathematicians in the years immedi- ately following their publication. Pour juger adkquatement le role de Riemann dans le developpement de la geometric differentielle sans etre influence outre mesure par sa reputation de trks grand mathematicien, nous devons &udier le contenu de ses travaux en geometric et prendre en consideration les reactions des autres mathematiciens au tours de trois an&es qui suivirent leur publication. Urn Riemann's Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Differentialgeometrie richtig einzuschZtzen, ohne sich von seinem Ruf als bedeutender Mathematiker iiberm;issig beeindrucken zu lassen, ist es notwendig den Inhalt seiner geometrischen Schriften und die Haltung zeitgen&sischer Mathematiker unmittelbar nach ihrer Verijffentlichung zu untersuchen. On June 10, 1854, Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann read his probationary lecture, "iber die Hypothesen welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen," before the Philosophical Faculty at Gdttingen ill. His biographer, Dedekind [1892, 5491, reported that Riemann had worked hard to make the lecture understandable to nonmathematicians in the audience, and that the result was a masterpiece of presentation, in which the ideas were set forth clearly without the aid of analytic techniques. -

Math 1320-9 Notes of 3/30/20 11.6 Directional Derivatives and Gradients

Math 1320-9 Notes of 3/30/20 11.6 Directional Derivatives and Gradients • Recall our definitions: f(x0 + h; y0) − f(x0; y0) fx(x0; y0) = lim h−!0 h f(x0; y0 + h) − f(x0; y0) and fy(x0; y0) = lim h−!0 h • You can think of these definitions in several ways, e.g., − You keep all but one variable fixed, and differentiate with respect to the one special variable. − You restrict the function to a line whose direction vector is one of the standard basis vectors, and differentiate that restriction with respect to the corresponding variable. • In the case of fx we move in the direction of < 1; 0 >, and in the case of fy, we move in the direction for < 0; 1 >. Math 1320-9 Notes of 3/30/20 page 1 How about doing the same thing in the direction of some other unit vector u =< a; b >; say. • We define: The directional derivative of f at (x0; y0) in the direc- tion of the (unit) vector u is f(x0 + ha; y0 + hb) − f(x0; y0) Duf(x0; y0) = lim h−!0 h (if this limit exists). • Thus we restrict the function f to the line (x0; y0) + tu, think of it as a function g(t) = f(x0 + ta; y0 + tb); and compute g0(t). • But, by the chain rule, d f(x + ta; y + tb) = f (x ; y )a + f (x ; y )b dt 0 0 x 0 0 y 0 0 =< fx(x0; y0); fy(x0; y0) > · < a; b > • Thus we can compute the directional derivatives by the formula Duf(x0; y0) =< fx(x0; y0); fy(x0; y0) > · < a; b > : • Of course, the partial derivatives @=@x and @=@y are just directional derivatives in the directions i =< 0; 1 > and j =< 0; 1 >, respectively. -

Derivatives Along Vectors and Directional Derivatives

DERIVATIVES ALONG VECTORS AND DIRECTIONAL DERIVATIVES Math 225 Derivatives Along Vectors Suppose that f is a function of two variables, that is, f : R2 → R, or, if we are thinking without coordinates, f : E2 → R. The function f could be the distance to some point or curve, the altitude function for some landscape, or temperature (assumed to be static, i.e., not changing with time). Let P ∈ E2, and assume some disk centered at p is contained in the domain of f, that is, assume that P is an interior point of the domain of f.This allows us to move in any direction from P , at least a little, and stay in the domain of f. We want to ask how fast f(X) changes as X moves away from P , and to express it as some kind of derivative. The answer clearly depends on which direction you go. If f is not constant near P ,then f(X) increases in some directions, and decreases in others. If we move along a level curve of f,thenf(X) doesn’t change at all (that’s what a level curve means—a curve on which the function is constant). The answer also depends on how fast you go. Suppose that f measures temperature, and that some particle is moving along a path through P . The particle experiences a change of temperature. This happens not because the temperature is a function of time, but rather because of the particle’s motion. Now suppose that a second particle moves along the same path in the same direction, but faster. -

Directional Derivatives

Directional Derivatives The Question Suppose that you leave the point (a, b) moving with velocity ~v = v , v . Suppose further h 1 2i that the temperature at (x, y) is f(x, y). Then what rate of change of temperature do you feel? The Answers Let’s set the beginning of time, t = 0, to the time at which you leave (a, b). Then at time t you are at (a + v1t, b + v2t) and feel the temperature f(a + v1t, b + v2t). So the change in temperature between time 0 and time t is f(a + v1t, b + v2t) f(a, b), the average rate of change of temperature, −f(a+v1t,b+v2t) f(a,b) per unit time, between time 0 and time t is t − and the instantaneous rate of f(a+v1t,b+v2t) f(a,b) change of temperature per unit time as you leave (a, b) is limt 0 − . We apply → t the approximation f(a + ∆x, b + ∆y) f(a, b) fx(a, b) ∆x + fy(a, b) ∆y − ≈ with ∆x = v t and ∆y = v t. In the limit as t 0, the approximation becomes exact and we have 1 2 → f(a+v1t,b+v2t) f(a,b) fx(a,b) v1t+fy (a,b) v2t lim − = lim t 0 t t 0 t → → = fx(a, b) v1 + fy(a, b) v2 = fx(a, b),fy(a, b) v , v h i·h 1 2i The vector fx(a, b),fy(a, b) is denoted ~ f(a, b) and is called “the gradient of the function h i ∇ f at the point (a, b)”. -

Relativistic Spacetime Structure

Relativistic Spacetime Structure Samuel C. Fletcher∗ Department of Philosophy University of Minnesota, Twin Cities & Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich August 12, 2019 Abstract I survey from a modern perspective what spacetime structure there is according to the general theory of relativity, and what of it determines what else. I describe in some detail both the “standard” and various alternative answers to these questions. Besides bringing many underexplored topics to the attention of philosophers of physics and of science, metaphysicians of science, and foundationally minded physicists, I also aim to cast other, more familiar ones in a new light. 1 Introduction and Scope In the broadest sense, spacetime structure consists in the totality of relations between events and processes described in a spacetime theory, including distance, duration, motion, and (more gener- ally) change. A spacetime theory can attribute more or less such structure, and some parts of that structure may determine other parts. The nature of these structures and their relations of determi- nation bear on the interpretation of the theory—what the world would be like if the theory were true (North, 2009). For example, the structures of spacetime might be taken as its ontological or conceptual posits, and the determination relations might indicate which of these structures is more fundamental (North, 2018). Different perspectives on these questions might also reveal structural similarities with other spacetime theories, providing the resources to articulate how the picture of the world that that theory provides is different (if at all) from what came before, and might be different from what is yet to come.1 ∗Juliusz Doboszewski, Laurenz Hudetz, Eleanor Knox, J. -

Lecture Notes of Thomas' Calculus Section 11.5 Directional Derivatives

Lecture Notes of Thomas’ Calculus Section 11.5 Directional Derivatives, Gradient Vectors and Tangent Planes Instructor: Dr. ZHANG Zhengru Lecture Notes of Section 11.5 Page 1 OUTLINE • Directional Derivatives in the Plane • Interpretation of the Directional Derivative • Calculation • Properties of Directional Derivatives • Gradients and Tangents to Level Curves • Algebra Rules for Gradients • Increments and Distances • Functions of Three Variables • Tangent Panes and Normal Lines • Planes Tangent to a Surface z = f(x, y) • Other Applications Why introduce the directional derivatives? • Let’s start from the derivative of single variable functions. Consider y = f(x), its ′ ′ derivative f (x0) implies the rate of change of f. f (x0) > 0 means f increasing as x ′ becomes large. f (x0) < 0 means f decreasing as x becomes large. • Consider two-variable function f(x, y). The partial derivative fx(x0,y0) implies the rate of change in the direction of~i while keep y as a constant y0. fx(x0,y0) > 0 implies increasing in x direction. Another interpretation, the vertical plane passes through (x0,y0) and parallel to x-axis intersects the surface f(x, y) in the curve C. fx(x0,y0) means the slope of the curve C. Similarly, The partial derivative fy(x0,y0) implies the rate of change in the direction of ~j while keep x as a constant x0. • It is natural to consider the rate of change of f(x, y) in any direction ~u instead of ~i and ~j. Therefore, directional derivatives should be introduced. ... Lecture Notes of Section 11.5 Page 2 Definition 1 The derivative of f at P0(x0,y0) in the direction of the unit vector ~u = u1~i + u2~j is the number df f(x0 + su1,y0 + su2) − f(x0,y0) = lim , ds s→0 s ~u,P0 provided the limit exists. -

A CONCISE MINI HISTORY of GEOMETRY 1. Origin And

Kragujevac Journal of Mathematics Volume 38(1) (2014), Pages 5{21. A CONCISE MINI HISTORY OF GEOMETRY LEOPOLD VERSTRAELEN 1. Origin and development in Old Greece Mathematics was the crowning and lasting achievement of the ancient Greek cul- ture. To more or less extent, arithmetical and geometrical problems had been ex- plored already before, in several previous civilisations at various parts of the world, within a kind of practical mathematical scientific context. The knowledge which in particular as such first had been acquired in Mesopotamia and later on in Egypt, and the philosophical reflections on its meaning and its nature by \the Old Greeks", resulted in the sublime creation of mathematics as a characteristically abstract and deductive science. The name for this science, \mathematics", stems from the Greek language, and basically means \knowledge and understanding", and became of use in most other languages as well; realising however that, as a matter of fact, it is really an art to reach new knowledge and better understanding, the Dutch term for mathematics, \wiskunde", in translation: \the art to achieve wisdom", might be even more appropriate. For specimens of the human kind, \nature" essentially stands for their organised thoughts about sensations and perceptions of \their worlds outside and inside" and \doing mathematics" basically stands for their thoughtful living in \the universe" of their idealisations and abstractions of these sensations and perceptions. Or, as Stewart stated in the revised book \What is Mathematics?" of Courant and Robbins: \Mathematics links the abstract world of mental concepts to the real world of physical things without being located completely in either".