Wu Yingjie ETDPITT2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subject Index

STP1042-EB/Jul. 1989 Subject Index A A 450/A 450M-86A, 151, 153 A 480/A 480M-84A, 151,153 Acicular ferrite, see Intragranular ferrite A 508-84a, 100-101,107, 114, 117 plates A 508/A 508-86, 115 AFNOR NF A 81460, 195 A 516/A 516M-84, 196 AISI 1215 steel, 51-66 A 530/A 530M-85a, 151,153 chemical analysis, 53, 56 A 533/A 533M-85b, 100-101, 106 experimental procedure, 53 A 588, 34 hardness, 53, 58 A 751, 1 machinability, 54-55, 58, 60-64 A 771-83, 124-125 MnS inclusion A 788, 202, 208 aspect ratio, residual effect, 53, 59 A 858/A 858M-86, 122 size, residual effect, 53, 58 A 860/A 860M-86, 122 oxide inclusion, 53-54, 59 E 8, 212 properties, 53-54, 56-59 E 23, 212 residual levels investigated, 52-53 E 45-76, 193 roto-bar rejection rate, 53, 56 E 112, 125, 212 tensile ductility and strength, residual ef- E 139-83, 126-127 fect, 57 E 618-81, 51, 53 Alloy steel G 5-82, 154 high strength, 266 G 31-72(1985), 154 relative cost of restricting residual levels, G 48-76(1980), 154 32-33 Auger spectroscopy, 100 Alumina inclusions, machinability, 72 Austenitic stainless steel Aluminum carbide contents, 160 content during ladle refining, 42-43 high temperature ductility, 164 deoxidation constant, 41 see also Titanium stabilized austenitic Aluminum oxide, 76 stainless steel Arc length, 243-258 Austenitization back-gouging, 257 martensitic 12% chromium steel, 88 deposit nitrogen and oxygen level effects, temperature, 113 251-256 Automatic screw machine test, 53-54 SMA electrodes, 257 Axisyrnmetric specimens, 100 specimen extraction and testing, 248 Ashby-Orowan -

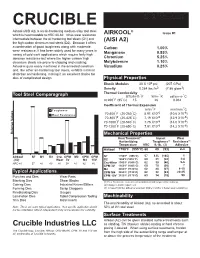

Crucible A2 Data Sheet

CRUCIBLE DATA SHEET Airkool (AISI A2) is an air-hardening medium alloy tool steel ® Issue #1 which is heat treatable to HRC 60-62. It has wear resistance AIRKOOL intermediate between the oil hardening tool steels (O1) and (AISI A2) the high carbon chromium tool steels (D2). Because it offers a combination of good toughness along with moderate Carbon 1.00% wear resistance, it has been widely used for many years in Manganese 0.85% variety of cold work applications which require fairly high abrasion resistance but where the higher carbon/ high Chromium 5.25% chromium steels are prone to chipping and cracking. Molybdenum 1.10% Airkool is quite easily machined in the annealed condition Vanadium 0.25% and, like other air-hardening tool steels, exhibits minimal distortion on hardening, making it an excellent choice for dies of complicated design. Physical Properties Elastic Modulus 30 X 106 psi (207 GPa) Density 0.284 lbs./in3 (7.86 g/cm3) Thermal Conductivity Tool Steel Comparagraph BTU/hr-ft-°F W/m-°K cal/cm-s-°C at 200°F (95°C) 15 26 0.062 Coefficient of Thermal Expansion ° ° Toughness in/in/ F mm/mm/ C ° ° -6 -6 Wear Resistance 70-500 F (20-260 C) 5.91 X10 (10.6 X10 ) 70-800°F (20-425°C) 7.19 X10-6 (12.9 X10-6) 70-1000°F (20-540°C) 7.76 X10-6 (14.0 X10-6) 70-1200°F (20-650°C) 7.91 X10-6 (14.2 X10-6) Relative Values Mechanical Properties Heat Treatment(1) Impact Wear Austenitizing Toughness(2) Resistance(3) Temperature HRC ft.-lb. -

Steels & Stainless Steels “Mini-CAS”

“Mini-CAS” course on Mechanical and Materials Engineering for Accelerators, 6/11/20-22/01/21 Steels & Stainless Steels Stefano Sgobba, EN-MME-MM, CERN - 20/11/2020 [email protected] Outline 1. Introduction to steels and stainless steels: • Iron and steel, major players in the history of mankind • Stainless steels, a 100 years of know-how 2. Rules for the selection and specification of stainless steels • Metallurgy of general purpose and advanced stainless steels grades/processes for specific applications 3. Steelmaking routes to secure the final quality of the product 4. Stability of the properties: precipitations and transformations • Considerations for welding • Case study: steel for the new CMS HG-CAL detector 5. Thermal treatments, sensitization, corrosion failures 6. Conclusions 20/11/2020 S. Sgobba - Steels & Stainless Steels 2 A. Berveglieri, R. Valentini, La Metallurgia Italiana, 1. Steels and stainless steel June 2001, p. 49ff Remains of Etruscan furnaces, exploited from the end of the Iron Age (9th – 8th century BC) to the 1st century BC Residues, exploited until 1969… Fe3O4 + CO 3FeO + CO2 FeO + CO Fe + CO2 FeO + C Fe + CO 20/11/2020 S. Sgobba - Steels & Stainless Steels 3 1. Steels and stainless steel C. Lemonnier, La Belgique, Paris, Hachette (1888) R. F. Tylecote. A history of metallurgy. The Metals Society, London, 2nd impr. 1979 20/11/2020 S. Sgobba - Steels & Stainless Steels 4 1. Steels and stainless steel Courtesy of TISCO /CN, hot rolling stainless steel plate mills, 2018 20/11/2020 S. Sgobba - Steels & Stainless Steels 5 1. Steels and stainless steel Courtesy of Sandvik Stainless Services 20/11/2020 S. -

Corrosion Hardness Effect of Steel Screws by Nanoindentation

CORROSION HARDNESS EFFECT OF STEEL SCREWS BY NANOINDENTATION Prepared by Duanjie Li, PhD 6 Morgan, Ste156, Irvine CA 92618 · P: 949.461.9292 · F: 949.461.9232 · nanovea.com Today's standard for tomorrow's materials. © 2017 NANOVEA INTRODUCTION As the most common failure mechanism in industry, corrosion of materials costs hundreds of billions of dollars annually to the U.S. economyi. It is critical to implement optimal corrosion control practices to improve lifecycle and asset management. Accelerated corrosion tests can substantially increase the measurement speed compared to those carried out in natural weathering. Laboratory corrosion tests that closely simulate the atmospheric effects on the corrosion mechanism of materials significantly facilitate the quality control and R&D of new materials and protective coatings for applications in aggressive environments. IMPORTANCE OF NANOINDENTATION TEST ON CORRODED METALS The mechanical properties of materials deteriorate during the corrosion process. For example, lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) and goethite (α-FeOOH) form in the atmospheric corrosion of carbon steel. Their loose and porous nature results in absorption of moisture and in turn further acceleration of the corrosion process ii . Akaganeite (β-FeOOH), another form of iron oxyhydroxide, is generated on the steel surface in chloride containing environments iii . Nanoindentation can control the indentation depth in the range of nanometers and microns, making it possible to quantitatively measure the hardness and Young’s modulus of the corrosion products formed on the metal surface. It provides physicochemical insight in corrosion mechanisms involved so as to select the best candidate material for the target applications. MEASUREMENT OBJECTIVE In this application, we showcased that the Nanovea Mechanical Tester in Nanoindentation mode measures the effect of rust in the corrosive media on the evolution of the mechanical properties of two types of steel screws. -

Reclaimed Metals in Various Applications

This packet provides information about how and why to use reclaimed metals in various applications. July Material Summary #1 Performance of Weathering Steel in Highway Bridges Material Summary #2 High-Performance Steel Reclaimed TxDOT Experience Summary of TxDOT experience using reclaimed metals in various applications Metals If you have questions or comments regarding this packet, contact: Rebecca Davio, TxDOT’s recycling coordinator (512) 416-2086 or [email protected] Almost all metals include some recycled Material Brief content. Steel and aluminum are used routinely in the road construction One of the keys to controlling the amount of industry, and they are both infinitely material thrown into landfills is to reuse reusable and recyclable. products as many times as possible. Reuse For example, aluminum sign blanks can conserves natural resources because fewer be used over and over again at less cost new products have to be manufactured. In than buying new blanks. Hydrostripping fact, reusing a material is often more resource- is a process that allows the reuse of ful than recycling it. Reuse eliminates exorbitant waste disposal Americans throw away enough fees and allows consumers to obtain raw aluminum every three months materials at a fraction of their original cost. to rebuild our entire commer- Furthermore, reuse reduces the quantity of cial air fleet. materials dumped in landfills while lessening damage to the environment. 1 aluminum signs that is much more effec- jumped by 27 percent. The Federal High- tive than sanding. Overview way Administration (FHWA) estimates nearly one-third of America’s 578,000 The process involves a high-pressure Steel bridges need to be repaired or replaced. -

Corrosion-Fatigue Evaluation of Uncoated Weathering Steel Bridges

applied sciences Article Corrosion-Fatigue Evaluation of Uncoated Weathering Steel Bridges Yu Zhang, Kaifeng Zheng, Junlin Heng * and Jin Zhu Department of Bridge Engineering, School of Civil Engineering, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu 610031, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-182-8017-6652 Received: 19 July 2019; Accepted: 19 August 2019; Published: 22 August 2019 Featured Application: The new findings highlight the enhancement in corrosion-fatigue performance of steel bridges by using the uncoated weathering steel. Besides, an innovative approach has been established to simulate the corrosion-fatigue process in uncoated weathering steel bridges, providing deep insights into the service life of the bridges. The approaches suggested in the article can be used (not limited to) as a reference for the research and design of uncoated weathering steel bridges. Abstract: Uncoated weathering steel (UWS) bridges have been extensively used to reduce the lifecycle cost since they are maintenance-free and eco-friendly. However, the fatigue issue becomes significant in UWS bridges due to the intended corrosion process utilized to form the corrodent-proof rust layer instead of the coating process. In this paper, an innovative model is proposed to simulate the corrosion-fatigue (C-F) process in UWS bridges. Generally, the C-F process could be considered as two relatively independent stages in a time series, including the pitting process of flaw-initiation and the fatigue crack propagation of the critical pitting flaw. In the proposed C-F model, Faraday’s law has been employed at the critical flaw-initiation stage to describe the pitting process, in which the pitting current is applied to reflect the pitting rate in different corrosive environments. -

Cold Rolled Steel Coils Arcelormittal Europe

ENVIRONMENTAL PRODUCT DECLARATION as per ISO 14025 and EN 15804 Owner of the Declaration ArcelorMittal Europe - Flat Products Programme holder Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V. (IBU) Publisher Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V. (IBU) Declaration number EPD-ARC-20200027-CBD1-EN ECO EPD Ref. No. ECO-00001269 Issue date 10/07/2020 Valid to 09/07/2025 Cold Rolled Steel Coils ArcelorMittal Europe www.ibu-epd.com | https://epd-online.com Umwelt Produktdeklaration Name des Herstellers – Name des Produkts General Information ArcelorMittal Europe Cold Rolled Steel Coils Programme holder Owner of the declaration IBU – Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V. ArcelorMittal Europe – Flat Products Panoramastr. 1 24-26 Boulevard d’Avranches 10178 Berlin L-1160 Luxembourg Germany Luxembourg Declaration number Declared product / declared unit EPD-ARC-20200027-CBD1-EN The declaration applies to 1 ton of cold rolled steel coil. This declaration is based on the product Scope: category rules: The Life Cycle Assessment is based on data collected Structural steels, 07.2014 from the ArcelorMittal plants producing Cold Rolled (PCR checked and approved by the SVR) Coils, representing 95 % of the annual production from 2015. Issue date 10/07/2020 The owner of the declaration shall be liable for the underlying information and evidence; the IBU shall not Valid to be liable with respect to manufacturer information, life cycle assessment data and evidences. 09/07/2025 Verification The standard EN 15804 serves as the core PCR Independent verification of the declaration and data according to ISO 14025:2010 Dipl. Ing. Hans Peters internally x externally (chairman of Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V.) Dr. -

Effect of Heat Treatment (Ferritizing) on Chemical Composition, Microstructure, Physical Properties and Corrosion Behaviour of Spheroidal Ductile Cast Iron

Asian Journal of Chemistry Vol. 19, No. 6 (2007), 4665-4673 Effect of Heat Treatment (Ferritizing) on Chemical Composition, Microstructure, Physical Properties and Corrosion Behaviour of Spheroidal Ductile Cast Iron A.R. ISMAEEL*, S.S. ABDEL REHIM† and A.E. ABDOU‡ Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Garyounis University, Benghazi, Libya E-mail: [email protected] Two steps ferritizing technique was applied on ductile cast iron samples by austenitizing at 900ºC, air cooling to produce pearlite, ferritizing by reheating samples for different times at 700ºC and air cooling to room temperature. Chemical analysis and microstructure showed that as ferritizing time increased, an increase of percentage of ferrite, decrease of pearlite, with corresponding decrease in cementite and increase of free carbon in the form of spheroidal graphite. These changes explain the changes of physical (mechanical) properties repre- sented in the increase of percentage elongation, decrease of tensile strength and decrease in brinle hardness. Weight loss corrosion test technique was followed for investigation of corrosion rate of heat treated samples in 0.1 N H2SO4 solution, which show decrease in corrosion rate with increased ferritizing time. This was explained due to decrease of cathodic sites represented in cementite forming pearlitic lamella. The exception was in the early step of ferritizing, where the corrosion rate increased due to formation of secondary graphite acting as effec- tive cathodic sites. Key Words: Ferritizing, Pearlite, Austenitizing, Microstructure, Cementite, Spheroidal graphite, Cathodic, Corrosion, Secondary graphite. INTRODUCTION Ductile (nodular or spherulitic graphite) cast iron in which a part or all of the carbon is present in the form of a tiny spherical balls, of average 33 to 37 µm1-4. -

Heat Treating of Aluminum Alloys

ASM Handbook, Volume 4: Heat Treating Copyright © 1991 ASM International® ASM Handbook Committee, p 841-879 All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1361/asmhba0001205 www.asminternational.org Heat Treating of Aluminum Alloys HEAT TREATING in its broadest sense, • Aluminum-copper-magnesium systems The mechanism of strengthening from refers to any of the heating and cooling (magnesium intensifies precipitation) precipitation involves the formation of co- operations that are performed for the pur- • Aluminum-magnesium-silicon systems herent clusters of solute atoms (that is, the pose of changing the mechanical properties, with strengthening from Mg2Si solute atoms have collected into a cluster the metallurgical structure, or the residual • Aluminum-zinc-magnesium systems with but still have the same crystal structure as stress state of a metal product. When the strengthening from MgZn2 the solvent phase). This causes a great deal term is applied to aluminum alloys, howev- • Aluminum-zinc-magnesium-copper sys- of strain because of mismatch in size be- er, its use frequently is restricted to the tems tween the solvent and solute atoms. Conse- specific operations' employed to increase quently, the presence of the precipitate par- strength and hardness of the precipitation- The general requirement for precipitation ticles, and even more importantly the strain hardenable wrought and cast alloys. These strengthening of supersaturated solid solu- fields in the matrix surrounding the coher- usually are referred to as the "heat-treat- tions involves the formation of finely dis- ent particles, provide higher strength by able" alloys to distinguish them from those persed precipitates during aging heat treat- obstructing and retarding the movement of alloys in which no significant strengthening ments (which may include either natural aging dislocations. -

Corrosion Control Plan for Bridges

Contents Introduction There is essentially no argument that the American infrastructure is in Introduction ................................................. i poor shape and there is little indication that significant improvement is on the horizon. Acknowledgments ....................................ii The amount of money needed to correct this problem is Executive Summary ..................................2 staggering, especially considering the current state of the economy. Crumbling Infrastructure ........................4 One reason for this is the age profile of the nation’s bridges. Figure 1 1 Introduction to Corrosion ......................6 shows this profile taken from the 2010 National Bridge Inventory . It shows bridges are approaching the maximum age distribution of Bridges to Everywhere ............................7 around 50 years. Most bridges were built for a 50 year design life, which means state highway departments will have to maintain those Corrosion Basics ...................................... 11 bridges beyond their original design lives, which will be challenging because they were built to lower design standards than those used Corrosion in Concrete ........................... 14 today. Exposure Conditions ............................. 18 Corrosion Control ................................... 21 The Highway Ahead .............................. 27 References ................................................. 29 Figure 1: Distribution of bridges by age (2010 NBI data) When the Eisenhower Interstate System was created, -

Crucible Steel Site

C~240:i ~.- tiXiUtlBJ IUrfS N70 If-tC· ,.),~ ..d-IN..~'.w~~.,f. LVNQi .................... L; t lAYI IflO ,- (. l~ ~l. FC'; ~~., ~ ( 'I'biiM ~ • Dul'kIn"- Jr •• 1fitora.y loJ' 'lAJ.AtLff JOHN r LYNCH ac IAAfO&'d ,laoe II J. S. C. •..,dc. JIIIW Jen~ 623-514) t.- 240.3 -9.9, 't7IUl:OA COURt' or .. JUSn C2IlUtC:DY DIV18JOIr ... uarsOll comrrr DOCiCItt 110. - JU&A.Ic VA.LLIT em ., COMC.tIII pubUo oorporation. .. ftAlwrlrr. ~' , -ft- gyu, ACtION CSISPIe\ lIT CAOCJIILa 'TD1. ClDalOU-TIOIr or Aaal~, 'aLDlJIQ M:lIUQJ. 1000 Iouth Pourt.b 'u••t Hard.on, -.v ".ne)'. 110 OOqlOnUon. hav1nog .ita principal oftice In the City ot . ... n, 'Oo\IAt)' Of ".u.. and 't.ate ot .WO .leney, .ar- ~.tl ... 1. ,ulAtUt u • body oorporate and politic. OJ'Nted• • tate ot Mew ".ney. 2. .1dlltUt• La .,.._te4 with tull pow.r and authority' and .u ch&rved with the duty ~ prevent the pollution ot the ..... ic tift%' aDd ita t.ributad ••• &Ad baa full power and au- thority to a •• which aU. power. &Ad duU •• are defined, ~te4 aDd hIpoaed aDder the la~ of the State of • ..., Jeruy. 1 '. = ;--.,· ... ; ..... 0 't'~~~ TIERRA-B-015617 . r .: a••• t forth In the Aevb.d Statute. of 11.-.oJ.uoy, 1937. '1'iUe . 58, Chapter 14, .a .uppl_ented and "'nded. '\. 3. Plaintiff further ahowl! that pur.uant to the powwr. and authority "..ted 1n it, W'Ider and by v1rtue of tho .tatute aforeaa14, the plAintiff. aet..1..n9W'Ider contract with certain -anicipalitl •• withln the ..... le valley S~rai. eo..LI.ionor.' C DbU'lct ••• def1Ae4 by 1IIv. -

BAT Guide for Electric Arc Furnace Iron & Steel Installations

Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı BAT Guide for electric arc furnace iron & steel installations Project TR-2008-IB-EN-03 Mission no: 2.1.4.c.3 Prepared by: Jesús Ángel Ocio Hipólito Bilbao José Luis Gayo Nikolás García Cesar Seoánez Iron & Steel Producers Association Serhat Karadayı (Asil Çelik Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş.) Muzaffer Demir Mehmet Yayla Yavuz Yücekutlu Dinçer Karadavut Betül Keskin Çatal Zerrin Leblebici Ece Tok Şaziye Savaş Özlem Gülay Önder Gürpınar October 2012 1 Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı Contents 0 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................ 12 1 INTRODUCTION. ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DIRECTIVE ON INDUSTRIAL EMISSIONS IN THE SECTOR OF STEEL PRODUCTION IN ELECTRIC ARC FURNACE ................................................................................. 14 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION OF THE SECTOR IN TURKEY ...................................................... 14 1.2.1 Current Situation ............................................................................................................ 14 1.2.2 Iron and Steel Production Processes............................................................................... 17 1.2.3 The Role Of Steel Sector in