COVID-19 Vaccine, an Update Pharmaceries Webinar March 23Rd, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety of Immunization During Pregnancy a Review of the Evidence

Safety of Immunization during Pregnancy A review of the evidence Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Immunizations

Medicine Summer 2015 | Volume 14, Number 2 encephalitis tetanus RUBELLA MUMPS meningococus pertussis ENCEPHALITIS MEASLES PERTUSSIS ROTAVIRUS meningococus MUMPS meningococus MEASLES tuberculosis RUBELLA diphtheria CHICKENPOX meningococus CHICKENPOX pneumococus meningococus rotavirus ENCEPHALITIS PNEUMOCOCUS FEVER TETANUS DIPHTHERIA TETANUS hepatitismumps POLIO encephalitis hepatitis measles pneumococus POLIO DIPHTHERIA FEVER CHICKENPOX tuberculosisRUBELLA tuberculosis diphtheria DIPHTHERIA meningococusMUMPS pneumococus encephalitis ENCEPHALITIS polio TETANUS diphtheria pertussis polio hepatitisRUBELLA meningococus ENCEPHALITIS DIPHTHERIA MEASLES YELLOW RUBELLA TETANUS measles Immunizations MEASLESpolio meningococus PERTUSSIS MEASLES RUBELLA measles tetanus rubella YELLOW tuberculosisENCEPHALITIS pneumococus CHICKENPOX RUBELLA measles What physicians rubella pertussis PNEUMOCOCUS need to know encephalitis diphtheria MUMPS meningococustetanus pneumococus measles rubella tetanus measles rotavirus tetanus rubellaPOLIOmeningococus hepatitisHEPATITISFEVER PERTUSSIS RUBELLA FEVER hepatitis FEVER HEPATITIS chickenpox poliorubella encephalitisTETANUSpertussis rubella DIPHTHERIA rotavirus tuberculosis FEVERHEPATITIS POLIO yellow DIPHTHERIAYELLOW polio pneumococus YELLOW polio ENCEPHALITIS chickenpoxrubellaRUBELLA rotavirus ENCEPHALITIS pertussis ROTAVIRUS tetanus chickenpox hepatitisFEVER encephalitis ENCEPHALITIS POLIO rotavirus ROTAVIRUS DIPHTHERIA YELLOW pertussis PNEUMOCOCUS PERTUSSIS RUBELLA polio CHICKENPOX ROTAVIRUS pneumococus CHICKENPOXCHICKENPOX -

Vaccines for Preteens

| DISEASES and the VACCINES THAT PREVENT THEM | INFORMATION FOR PARENTS Vaccines for Preteens: What Parents Should Know Last updated JANUARY 2017 Why does my child need vaccines now? to get vaccinated. The best time to get the flu vaccine is as soon as it’s available in your community, ideally by October. Vaccines aren’t just for babies. Some of the vaccines that While it’s best to be vaccinated before flu begins causing babies get can wear off as kids get older. And as kids grow up illness in your community, flu vaccination can be beneficial as they may come in contact with different diseases than when long as flu viruses are circulating, even in January or later. they were babies. There are vaccines that can help protect your preteen or teen from these other illnesses. When should my child be vaccinated? What vaccines does my child need? A good time to get these vaccines is during a yearly health Tdap Vaccine checkup. Your preteen or teen can also get these vaccines at This vaccine helps protect against three serious diseases: a physical exam required for sports, school, or camp. It’s a tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough). good idea to ask the doctor or nurse every year if there are any Preteens should get Tdap at age 11 or 12. If your teen didn’t vaccines that your child may need. get a Tdap shot as a preteen, ask their doctor or nurse about getting the shot now. What else should I know about these vaccines? These vaccines have all been studied very carefully and are Meningococcal Vaccine safe. -

Meningococcal Vaccine Q & a for Healthcare Providers

Meningococcal Vaccine Q & A for Healthcare Providers School meningococcal vaccine requirements Q1: When did the school meningococcal vaccine requirement take effect? A1: The meningococcal vaccine school requirement took effect on September 1, 2016. Q2: For what grades is meningococcal vaccine required? A2: Meningococcal vaccine is currently required for students entering or attending grades 7 through 12 in public, private and parochial New York State (NYS) schools. Q3: How many doses of meningococcal vaccine are required for grades 7 through 11? A3: One dose of meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY; sometimes abbreviated as MCV4; brand names Menactra or Menveo) is required for entry into grades 7 through 11. Q4: How many doses of meningococcal vaccine are required for grade 12? A4: A total of two doses of MenACWY vaccine, administered a minimum of 8 weeks apart, are required for entry into grade 12. The second dose must be administered no sooner than 16 years of age. However, if the first dose of MenACWY vaccine was received at 16 years of age or older, then a second dose will not be required. The NYS school immunization requirements allow for a grace period of up to 4 days before the 16th birthday for receipt of the dose. A dose of vaccine received 5 or more days before the 16th birthday will not meet the 12th grade meningococcal vaccine requirement. Q5: Is serogroup B meningococcal vaccine (MenB vaccine) required for grade 12? A5: No, MenB vaccine is not required for school attendance in NYS. In addition, doses of MenB vaccine will not meet the NYS MenACWY vaccine requirement. -

Bill 2015 - Submission to the Senate Enquiry

Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 12/10/2015 Dear Sir/Madam, Re: Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab No Pay) Bill 2015 - submission to the Senate enquiry My objections to the No Jab No Pay bill are outlined as follows: 1) 'Motivating' people financially targets the less well off only. The majority of previous conscious objectors are the well educated and higher earning class. It will force women out of the workforce and will not achieve a notable difference in vaccination rates or reduce disease. 2) The 'No Jab No Pay' policy is not targeting those who have forgotten to vaccinate but those who previously would have consciously objected to vaccinating. In a democratic society, it should not be possible to rule in favour of forcing medical procedures onto members of the public, particularly into the children of people who disagree fundamentally with the process. It would be a very sad day for Australia if medical procedures were forced on members of the public who genuinely believe it could harm them. To force not only unavoidably unsafe procedures but future unknown and untested medical procedures in indeterminable amounts on the children whose parents are not convinced of the safety or efficacy of such procedures, puts an end to freedom of choice, an end to human rights for Australians. 3) The science is NOT clear. The government and policy makers may have only been presented with one sided research but I reiterate, the science is NOT clear. Please see the attached list of peer reviewed research that offer information that may not otherwise have been presented to policy makers. -

PROOF of IMMUNIZATION COMPLIANCE NORTHWESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY of LOUISIANA (Louisiana R.S

PROOF OF IMMUNIZATION COMPLIANCE NORTHWESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY OF LOUISIANA (Louisiana R.S. 17:170.1 Schools of Higher Learning) SS Number: _____________________________________________ Date of Birth: Month _________________ Date ___________________ Year ________________ Name: __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Please Print (Last) (First) (Middle) Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City: ______________________________________________________ State: ________________________________ ZIP Code: _____________________________ UNIVERSITY REQUIRED IMMUNIZATIONS: Physician or Other Health Care Provider Verification: (See other side) M-M-R (Measles, Mumps, Rubella-2 Doses Required) Tetanus Diphtheria (Td) Pertussis (Tdap) OR First dose: ___________________ Serologic Test: __________________ Td: ___________________ (Date) (Date within 10 years) (Date) OR Second dose: __________________ (Date) Result: _________________________ (Date) Tdap: ___________________ (Date within 10 years) OR □ Born before 1956 Meningitis Vaccine ACYW-135 (TWO doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccination separated by at least eight weeks.) First dose: ____________________________________ Vaccine Type: _______________________________________ (Date) Second dose: __________________________________ Vaccine Type: _______________________________________ (Date) UNIVERSITY REQUIRED IMMUNIZATIONS: -

COVID-19 Vaccines: Summary of Current State-Of-Play Prepared Under Urgency 21 May 2020 – Updated 16 July 2020

Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor Kaitohutohu Mātanga Pūtaiao Matua ki te Pirimia COVID-19 vaccines: Summary of current state-of-play Prepared under urgency 21 May 2020 – updated 16 July 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred a global effort to find a vaccine to protect people from SARS- CoV-2 infection. This summary highlights selected candidates, explains the different types of vaccines being investigated and outlines some of the potential issues and risks that may arise during the clinical testing process and beyond. Key points • There are at least 22 vaccine candidates registered in clinical (human) trials, out of a total of at least 194 in various stages of active development. • It is too early to choose a particular frontrunner as we lack safety and efficacy information for these candidates. • It is difficult to predict when a vaccine will be widely available. The fastest turnaround from exploratory research to vaccine approval was previously 4–5 years (ebolavirus vaccine), although it is likely that current efforts will break this record. • There are a number of challenges associated with accelerated vaccine development, including ensuring safety, proving efficacy in a rapidly changing pandemic landscape, and scaling up manufacture. • The vaccine that is licensed first will not necessarily confer full or long-lasting protection. 1 Contents Key points .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Types of vaccines ............................................................................................................... -

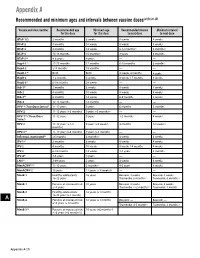

Recommended and Minimum Ages and Intervals Between Doses

Appendix A Recommended and minimum ages and intervals between vaccine doses(a),(b),(c),(d) Vaccine and dose number Recommended age Minimum age Recommended interval Minimum interval for this dose for this dose to next dose to next dose DTaP-1(e) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks DTaP-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks DTaP-3 6 months 14 weeks 6-12 months(f) 6 months(f) DTaP-4 15-18 months 15 months(f) 3 years 6 months DTaP-5(g) 4-6 years 4 years — — HepA-1(e) 12-23 months 12 months 6-18 months 6 months HepA-2 ≥18 months 18 months — — HepB-1(h) Birth Birth 4 weeks-4 months 4 weeks HepB-2 1-2 months 4 weeks 8 weeks-17 months 8 weeks HepB-3(i) 6-18 months 24 weeks — — Hib-1(j) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks Hib-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks Hib-3(k) 6 months 14 weeks 6-9 months 8 weeks Hib-4 12-15 months 12 months — — HPV-1 (Two-Dose Series)(l) 11-12 years 9 years 6 months 5 months HPV-2 11-12 years (+6 months) 9 years +5 months(m) — — HPV-1(n) (Three-Dose 11-12 years 9 years 1-2 months 4 weeks Series) HPV-2 11-12 years (+1-2 9 years (+4 weeks) 4 months 12 weeks (n) months) HPV-3(n) 11-12 years (+6 months) 9 years (+5 months) — — Influenza, inactivated(o) ≥6 months 6 months(p) 4 weeks 4 weeks IPV-1(e) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks IPV-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks-14 months 4 weeks IPV-3 6-18 months 14 weeks 3-5 years 6 months IPV-4(q) 4-6 years 4 years — — LAIV(o) 2-49 years 2 years 4 weeks 4 weeks MenACWY-1(r) 11-12 years 2 months(s) 4-5 years 8 weeks MenACWY-2 16 years 11 years (+ 8 weeks)(t) — — MenB-1 Healthy adolescents: 16 -

A POX at Your House Chickenpox Parties Are an Old-School Method to Expose Kids to the Disease, but Are They Safe Alternatives Natural, Lifelong Immunity

A POX at Your House Chickenpox parties are an old-school method to expose kids to the disease, but are they safe alternatives natural, lifelong immunity. Web sites such as diyfather.com or to an effective vaccine? “Chickenpox is a normal child- mothering.com give tips on how to by Sarah McCoy hood illness and I would rather not host a pox party with as much gusto vaccinate against a relatively minor as a birthday bash. sickness that will give permanent im- Parents who choose to enlist their Chickenpox parties are meant to munity,” says Jessica DelBalzo, moth- children in such parties claim they’ve be unsanitary. Children swap whis- er of two children, ages 2 and 6, who done their homework, weighed the tles, cups, lollipops and are encour- is desperately seeking a chickenpox risks and benefi ts, and made a thought- aged to cough without covering their party in Flemington, N.J. ful choice. mouths. The goal is to ensure every- Statistics on such parties are dif- Still, many in the medical commu- one gets some quality time with the fi cult to fi nd, but according to a nity shake their heads at such ideas. guest of honor, the varicella zoster vi- study done by the American Acade- “If parents came into my offi ce and rus, which lives in airborne respirato- my of Pediatricians, the chickenpox said they were going to a chickenpox ry droplets and is highly contagious. vaccine is the second most refused party, I would tell them that they were Parents who are more afraid of by parents, behind only the mea- putting their child’s life in danger,” says exposing their children to vaccines sles, mumps and rubella. -

Artículos Científicos

Editor: NOEL GONZÁLEZ GOTERA Número 064 Diseño: Lic. Roberto Chávez y Liuder Machado. Semana 291212 - 040113 Foto: Lic. Belkis Romeu e Instituto Finlay La Habana, Cuba. ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS P ublicaciones incluidas en P ubMED durante el período comprendido entre el 29 de diciembre de 2012 y el 4 de enero de 2013. Total de artículos reuperados con “vaccin*” en título: 68 Vacunas meningococo (Neisseria meningitidis) 13. Up take of meningococcal va ccine in Arizona schoolchildren after implementation of school- entry immunization requirements. Simpson JE, Hills RA, Allwes D, Rasmussen L. Public Health Rep. 2013 Jan;128(1):37-45. PMID: 23277658 [PubMed - in process] Related citations 33. A cute Cerebellar Ataxia Following Meningococcal Group C Conjugate V accination. Cutroneo PM, Italiano D, Trifirò G, Tortorella G, Russo A, Isola S, Caputi AP, Spina E. J Child Neurol. 2012 Dec 28. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 23275434 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher] Related citations 39. Preclinical safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a nonavalent PorA native outer m embrane vesicle va ccine against serogroup B meningococcal disease. Kaaijk P, van Straaten I, van de Waterbeemd B, Boot EP, Levels LM, van Dijken HH, van den Dobbelsteen GP. 1 Vaccine. 2012 Dec 27. doi:pii: S0264-410X(12)01815-4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.031. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 23273968 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher] Related citations 40. P riorities for research on meningocccal disease and the impact of serogroup A va ccination in the African meningitis belt. [No authors listed] Vaccine. 2012 Dec 27. doi:pii: S0264-410X(12)01820-8. -

HPV and Adolescent Vaccine Toolkit: Clinician Guide Contents

HPV and Adolescent Vaccine Toolkit: Clinician Guide CONTENTS I. 2018 IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULES & SCREENING RESOURCES Recommended & Catch-up Immunization Schedule (Birth-18 Years) Lists the ages or age range each vaccine is recommended. Schedules are updated annually. Please visit https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/ for the most up-to-date schedules. Clinician FAQ: CDC Recommendations for HPV Vaccine 2-Dose Schedules Helps explain the new HPV vaccine recommendation for adolescents (2 doses recommended for adolescents starting the series before their 15th birthday; 3 doses recommended for adolescents starting the series after their 15th birthday) and provides tips for talking to parents about the change. HPV 2-Dose Decision Tree Follow the decision tree chart to determine whether your patient needs two or three doses of HPV vaccine. II. ADDRESSING VACCINE HESITANCY Talking to Parents About the HPV Vaccine A collection of questions parents may have surrounding the HPV vaccine and responses healthcare providers can use to address the concerns. Let’s Talk Vaccines: A Guide to Conversations About Immunizations Parents ask tough questions! Use this resource from Northwest Vax to provide a strong recommendation using the Ask. Acknowledge. Advise model. III. BEST PRACTICES AND STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVING IMMUNIZATION COVERAGE RATES Strategies for Improving Adolescent Immunization Coverage Rates Use the strategies in this AAP resource to help your practice improve adolescent immunization coverage rates among your patients. Documenting Parental Refusal to Have Their Children Vaccinated Provides tips from the AAP on ways to communicate with and educate parents who refuse immunizations. Includes a template for use by health care providers to document refusals. -

1 What Is the Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccinations in Preventing Disease Transmission to the Non-Vaccinated?

National Health Library and Knowledge Service | Evidence Team CURRENT AS AT 02 April 2021 Summary of Evidence: COVID-19 | Question 199 VERSION 1.0 The following information resources have been selected by the National Health Library and Knowledge Service Evidence Virtual Team in response to a question from the National Immunisation Advisory Committee (NIAC). The resources are listed in our estimated order of relevance to practicing healthcare professionals confronted with this scenario in an Irish context. In respect of the evolving global situation and rapidly changing evidence base, it is advised to use hyperlinked sources in this document to ensure that the information you are disseminating to the public or applying in clinical practice is the most current, valid and accurate. For further information on the methodology used in the compilation of this document including a complete list of sources consulted please see our National Health Library and Knowledge Service Summary of Evidence Protocol. QUESTION 199 What is the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations in preventing disease transmission to the non-vaccinated? Question 199 was prepared by the National Health Library and Knowledge Service in collaboration with the Research Subgroup of the National Immunisation Advisory Committee (NIAC). National Health Library and NIAC Knowledge Service | Evidence Team 1 National Health Library and Knowledge Service | Evidence Team CURRENT AS AT 02 April 2021 Summary of Evidence: COVID-19 | Question 199 VERSION 1.0 What is the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations in preventing disease transmission to the non-vaccinated? Main Points 1. Emerging evidence suggests that COVID-19 vaccines may also reduce asymptomatic infection, and potentially transmission.