E Ogil in English: Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xena and Buffy

Frances Early, Kathleen Kennedy, eds.. Athena's Daughters: Television's New Women Warriors. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003. 175 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8156-2968-9. Reviewed by Robin Riley Published on H-Peace (May, 2004) It is a strange experience to be reading and each represent, at least, "a girl-power hero--a writing about "television's new women warriors" young, hip, and alluring portrayal of female au‐ when television and the nation have actual wom‐ tonomy that offers an implicit contrast to and cri‐ en warriors with whom we have recently ob‐ tique of the second-wave feminist generation that sessed. Could it be that the presence of fctitious came of age in the 1960s and 1970s" (p. 3). The women warriors helped to conceptually prepare question of whether or not these characters or se‐ us for Jessica Lynch? ries represent a move towards female just war‐ Fans of Xena, Warrior Princess (as the au‐ riors, contain critiques of war, or are attempting thors say, hereafter XWP) and Buffy the Vampire to subvert traditional ways of thinking about gen‐ Slayer (not similarly acronymed) will enjoy this der and war, appears and disappears across the collection. Athena's Daughters is flled with plot collection's essays. references to episodes from the Xena and Buffy Frances Early and Kathleen Kennedy are dis‐ "verses," as well as two essays from authors fo‐ mayed at this turn toward "girl power heroes" cusing on the La Femme Nikita and Star Trek Voy‐ with its accompanying de-politicization of gender ager_ series. -

The SRAO Story by Sue Behrens

The SRAO Story By Sue Behrens 1986 Dissemination of this work is made possible by the American Red Cross Overseas Association April 2015 For Hannah, Virginia and Lucinda CONTENTS Foreword iii Acknowledgements vi Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Prologue Page One PART ONE KOREA: 1953 - 1954 Page 1 1955 - 1960 33 1961 - 1967 60 1968 - 1973 78 PART TWO EUROPE: 1954 - 1960 98 1961 - 1967 132 PART THREE VIETNAM: 1965 - 1968 155 1969 - 1972 197 Map of South Vietnam List of SRAO Supervisors List of Helpmate Chapters Behrens iii FOREWORD In May of 1981 a group of women gathered in Washington D.C. for a "Grand Reunion". They came together to do what people do at reunions - to renew old friendships, to reminisce, to laugh, to look at old photos of them selves when they were younger, to sing "inside" songs, to get dressed up for a reception and to have a banquet with a speaker. In this case, the speaker was General William Westmoreland, and before the banquet, in the afternoon, the group had gone to Arlington National Cemetery to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. They represented 1,600 women who had served (some in the 50's, some in the 60's and some in the 70's) in an American Red Cross program which provided recreation for U.S. servicemen on duty in Europe, Korea and Vietnam. It was named Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). In Europe it was known as the Red Cross center program. In Korea and Vietnam it was Red Cross clubmobile service. -

DISSO FULL DOCUMENT With

From Zero to My Own Hero: An Intersectional Feminist Analysis of the Woman Superhero’s Challenge to Humanity in Watchmen and Jessica Jones Louise Stenbak Simonsen & Sabina Kox Thorsen 10th semester, MA Dissertation Engelsk Almen, Aalborg University Supervisor: Mia Rendix 02-06-2020 Characters: 317649 Simonsen & Thorsen 1 Abstract The image of women in the superhero genre has for many years been dominated by how it is produced as a mirror to the masculine. However, this image is now beginning to be disrupted by feminist attempts at diversifying representations. This paper aims to examine Watchmen and the first season of Jessica Jones as cultural representations and new voices of women which materialise the category as a transgressive, challenging force to assumedly fixed structures of gender, race and sexuality. As Jessica Jones speaks from a White feminist perspective, and Watchmen from a Black feminist perspective, we explore how the texts can be combined to expand the category of women. The texts show the discourses, regimes of truth, and forms of violence which seek to regulate women, and in exposing these tools of domination, the texts disrupt the fixed categories and definitions of women and question the limits of performativity. In spite of women being shown to be materialised beyond the phallogocentric economy of signification, the two series still limit gender to a biological determinism that assumes a normativity of social structures and relations of power. However, because the texts are voices of women, they are the first step of many towards a multitude of untold, endless possibilities of gender and racial representation. -

Tuesday Morning, May 8

TUESDAY MORNING, MAY 8 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Ricky Martin; Giada De Live! With Kelly Stephen Colbert; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Laurentiis. (N) (cc) (TV14) Miss USA contestants. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Rhyming Block. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Three new nursery rhymes. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Iden- 12/KPTV 12 12 tity Crisis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the It’s Supernatural Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) (TVG) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (N) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court (N) The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter A fugitive and Criminal Minds The team must Criminal Minds Hotch has a hard CSI: Miami Inside Out. -

3.50 Story by Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti

http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl 1. PAINKILLER JANE #1 Price: $3.50 STORY BY JOE QUESADA AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI; WRITTEN BY JIMMY PALMIOTTI; ART BY LEE MODER; COVER ART BY RON ADRIAN, STJEPAN SEJIC, GEORGES JEANTY, AND AMANDA CONNER Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! Picking up from the explosive events of issue #0, PKJ #1 hits the ground running as Jane faces international terrorists and the introduction of a brand new character - "The Infidel" who will change her world forever! Featruing cover art by Ron (Supergirl, RED SONJA) Adrian, Georges (Buffy) Jeanty, Amanda (Supergirl) Conner, and Stjepan (Darkness) Sejic! Find out for yourself why reviewers have described Jane and her creators as "Jimmy Palmiotti has a sick, twisted imagination, and he really cut it loose here. But the book really works because Lee Moder draws the hell out of it, depicting every gruesome moment with grisly adoration for the script." (Marc Mason, ComicsWaitingRoom.com) FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER BLACK AND WHITE SKETCH INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE RON ADRIAN NEGATIVE ART INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER VARIANT SIGNED BY AMANDA CONNER AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI! 2. PAINKILLER JANE #1 - RON ADRIAN COVER AVAILABLE AS A BLOOD RED FOIL Price: $24.95 Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Sparks from a Busy Anvil

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Gilpin, John R., 1905-1974 Library of Appalachian Preaching 1937 Sparks from a Busy Anvil John R. Gilpin Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/gilpin_johnr Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Gilpin, John R., "Sparks from a Busy Anvil" (1937). Gilpin, John R., 1905-1974. 1. https://mds.marshall.edu/gilpin_johnr/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library of Appalachian Preaching at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gilpin, John R., 1905-1974 by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ''Sparks from Busy Anvil'' ,W By 252 . G489s JOHN R. GILPIN I - ,. I ' ' ., " " • Radio Messages from First Baptist Church Russell, Kentucky MARSHALL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY WEST VIRGINIANA COLLECTION • "Sparks from a Busy Anvil" By JOHN R. GILPIN .. • Radio Messages from First Baptist Church Russel I, Kentucky (From Moy 30, 1937-August 22, 1937 ) • To A glorious Christian cha racter, to whom I owe a debt, which H eaven alone can pay, MY BELOVED WIFE this volume is affectionately dedicat ed . • • • Foreword When I was seventeen years old, I was called into the ministry. For the past fifteen years, I have been trying to preach the Gospel. All of these thirty-two years have been spent in school: grammar, high, college, seminary, and the school of practical experience. Dur ing these years of schooling, I have only learned three lessons that are really worth-while. -

'Ripley's Believe It Or

For Immediate Release: BELIEVE IT OR NOT, TRAVEL CHANNEL GREENLIGHTS THE REBOOT OF THE ICONIC ‘RIPLEY’S BELIEVE IT OR NOT!’ HOSTED BY ACTOR BRUCE CAMPBELL Veteran actor Bruce Campbell is executive producer and host of the reboot of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” NEW YORK (January 2, 2019) – Ripley’s Believe It or Not! has cornered the market on the extraordinary, the death defying, the odd and the unusual. Now, 100 years after Robert L. Ripley launched the brand, the phrase Believe It or Not! is known globally and has come to symbolize how we marvel at the wonders of our world. Travel Channel is rebooting the iconic series, hosted by veteran actor Bruce Campbell (Evil Dead, Burn Notice), with 10 all-new, one-hour episodes that will showcase the most astonishing, real and one-of-a- kind stories. Currently in production, the series will be shot on location at the famed Ripley Warehouse in Orlando, Florida, and will incorporate incredible stories from all parts of the globe — from Brazil to Baltimore. The series is slated to premiere in summer 2019. As part of the 100th anniversary celebration of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, Campbell rang in the new year in Times Square with the New Year’s Eve Ball Drop along with millions of new friends. “As an actor, I’ve always been drawn toward material that is more ‘fantastic’ in nature, so I was eager and excited to partner with Travel Channel and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! on this new show,” said Campbell. -

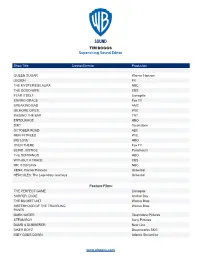

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Feature Films

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production QUEEN SUGAR Warner Horizon LEGION FX THE MYSTERIES/LAURA NBC THE GOOD WIFE CBS FEAR ITSELF Lionsgate SAVING GRACE Fox TV BREAKING BAD AMC GILMORE GIRLS. W.B. RAISING THE BAR TNT ENTOURAGE HBO DIRT Touchstone OCTOBER ROAD ABC MEN IN TREES W.B. BIG LOVE HBO OVER THERE Fox TV BLIND JUSTICE Paramount THE SOPRANOS HBO WITHOUT A TRACE CBS MR. STERLING NBC XENA: Warrior Princess Universal HERCULES: The Legendary Journeys Universal Feature Films: THE PERFECT GAME Lionsgate SURFER, DUDE Anchor Bay THE BUCKET LIST Warner Bros. SISTERHOOD OF THE TRAVELING Warner Bros. PANTS DARK WATER Touchstone Pictures STEAM BOY Sony Pictures DUMB & DUMBERER New Line BIKER BOYZ Dreamworks SKG IGBY GOES DOWN Atlantic Streamline www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production WE WERE SOLDIERS Icon HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES Universal TRIXIE Sand Castle 5 Productions WALKING ACROSS EGYPT Mitchum Entertainment THE END OF VIOLENCE MGM THE LESSER EVIL Moon Dog Productions WASHINGTON SQUARE Hollywood Pictures LOST HIGHWAY October Films DEMON KNIGHT Universal ABOVE THE RIM New Line Cinema BLANK CHECK Disney HOUSE PARTY 3 New Line Cinema THE GLASS SHIELD Miramax DARKMAN III Universal DARKMAN II Universal Television/Cable Movies (Adr Supervisor) AMAZON HIGH Universal Home Ent. ANOTHER MIDNIGHT RUN Universal Television ASSAULT AT WEST POINT Showtime ATTACK OF THE 5’2’’ WOMAN Showtime BLIND JUSTICE HBO Pictures COLOR OF JUSTICE Showtime CONVICTION CBS THE COURTYARD Showtime DARK REFLECTIONS Fox FULL BODY MASSAGE Showtime FULL ECLIPSE HBO Pictures GANG IN BLUE Showtime HERCULES AND THE AMAZON Universal WOMEN HERCULES AND THE LOST KING- Universal DOM HERCULES AND THE CIRCLE OF Universal FIRE www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production HERCULES IN THE UNDERWORLD Universal HERCULES AND THE MAZE OF Universal THE MINOTAUR HERCULES: THE FIGHT FOR Universal Home Ent. -

The Warriors Princess Free

FREE THE WARRIORS PRINCESS PDF Barbara Erskine | 480 pages | 17 Mar 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007174294 | English | London, United Kingdom Thus, the Adventures of Mum and Princess was created Join us on an FB Live chat today at The Warriors Princess. Khutulun deserves her own place in history However, even among the standards of all those powerful Mongol women, Khutulun writes a distinct place for herself. Born aboutKhutulun, was the great-great granddaughter of Genghis Khan and a legend in her own right. Unlike her cousin, the emperor Kublai Khan, who relished the comfort and luxuries of the Chinese court, Khutulun chose the rough, nomadic lifestyle — the traditional Mongol way of life. Benevolently imaged as beautiful, and much sought after by men, Khutulun was a woman of extraordinary strength. She mastered the Mongol arts of horse-riding, archery, and wrestling where she eventually became the champion wrestler whom no man could defeat. She also transcended at the cardinal Mongol vocation of warfare. However, it is important to note that it was not unusual for Mongolians to see women on horses or dealing with bows and arrows, but what made Khutulun an anomaly was her excellence, the refinement of her skills among many of her likes. Her father, Qaidu Khan, awarded her a gergee a medal of office that stated the power of the holder as an acknowledgement of her power and independence. She is the only woman recorded to have received that, as it was an authority usually The Warriors Princess for men. Khutulun outperformed all her fourteen brothers since a very early age. -

The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess

−1− CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL ONTARIO REGIONAL COUNCIL CFPL-TV re episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess (CBSC Decision 98/99-0306) Decided June 17, 1999 A. MacKay (Chair), R. Stanbury (Vice-Chair), R. Cohen (ad hoc), P. Fockler, M. Hogarth and M. Ziniak THE FACTS On February 7, 1999, beginning at 4 pm, CFPL-TV (London) aired back-to-back episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess, both of which are tongue-in-cheek action-packed fantasy shows, loosely based in Greek mythology. In the particular episode of Hercules viewed by the Council, the legendary hero travels to a parallel universe where he meets his “evil” twin. The twin is in love with “The Empress”, a provocatively dressed, ruthless and impetuous woman who likes to feel her power and who harbours a desire to conquer the world. The twin is stabbed early on in the episode, leaving the real Hercules to take his place and attempt to set things right. His efforts to do so force him to take on Aries, the God of War, in battle, to escape from a large dragon snake and to fight the Empress herself. Not surprisingly, there are many scenes depicting violent acts in the program, but most of these are presented as acrobatic and often as humourous moments. On the few occasions in which any blood is shown, the scenes do not include the actual infliction of the wound or the physical wound itself, but rather blood on peripheral objects to suggest the wound. Examples include the filming of “blood” on a rock next to which lies the unconcious twin and, later in the show, the knife which killed the evil twin is shown covered in blood. -

6Th Grade Recommended Reading Friday, November 25, 2011 6:36:02 PM Emmaus Lutheran School Sorted By: Title

AR BookGuide™ Page 1 of 109 6th Grade Recommended Reading Friday, November 25, 2011 6:36:02 PM Emmaus Lutheran School Sorted by: Title Quiz Word Title Author Number Lang IL BL Pts F/NF Count Book RP RV LS VP Description 1634: The Galileo Affair Flint, Eric 86429 EN UG 6.5 31.0 F 189329 N N - - - Mike Stearns, leader of a group of West Virginians accidentally plunged into seventeenth-century Germany in the midst of the Thirty Years War, spearheads the formation of the United States of Europe. The coauthor is Andrew Dennis. The Abduction Newth, Mette 6030 EN UG 6.0 8.0 F 50015 N N - - N Two Inuit young people are abducted by traders, and another girl awaits the return of her father who is on a trade mission. This story is based on the actual kidnapping of Inuit Eskimos by European traders in the 17th century. Abyss Denning, Troy 132766 EN UG 6.7 17.0 F 104138 N N - - - Sojourning among the mysterious Aing- Tii monks has left Luke and his son Ben with no real answers, only the suspicion that the revelations they seek lie in the forbidden reaches of the distant Maw Cluster. Book #3 Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 102 EN MG 6.6 10.0 F 61778 N N - N N A moving story of the Civil War and one boy who grew up at home. Across Frozen Seas Wilson, John 45006 EN MG 6.0 5.0 F 30279 N N - - - This book explores the vast territory of the 1845 Franklin Expedition, travelling aboard the ill-fated vessel H.M.S.