Xena and Buffy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.50 Story by Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti

http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl 1. PAINKILLER JANE #1 Price: $3.50 STORY BY JOE QUESADA AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI; WRITTEN BY JIMMY PALMIOTTI; ART BY LEE MODER; COVER ART BY RON ADRIAN, STJEPAN SEJIC, GEORGES JEANTY, AND AMANDA CONNER Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! Picking up from the explosive events of issue #0, PKJ #1 hits the ground running as Jane faces international terrorists and the introduction of a brand new character - "The Infidel" who will change her world forever! Featruing cover art by Ron (Supergirl, RED SONJA) Adrian, Georges (Buffy) Jeanty, Amanda (Supergirl) Conner, and Stjepan (Darkness) Sejic! Find out for yourself why reviewers have described Jane and her creators as "Jimmy Palmiotti has a sick, twisted imagination, and he really cut it loose here. But the book really works because Lee Moder draws the hell out of it, depicting every gruesome moment with grisly adoration for the script." (Marc Mason, ComicsWaitingRoom.com) FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER BLACK AND WHITE SKETCH INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE RON ADRIAN NEGATIVE ART INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER VARIANT SIGNED BY AMANDA CONNER AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI! 2. PAINKILLER JANE #1 - RON ADRIAN COVER AVAILABLE AS A BLOOD RED FOIL Price: $24.95 Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! -

'Ripley's Believe It Or

For Immediate Release: BELIEVE IT OR NOT, TRAVEL CHANNEL GREENLIGHTS THE REBOOT OF THE ICONIC ‘RIPLEY’S BELIEVE IT OR NOT!’ HOSTED BY ACTOR BRUCE CAMPBELL Veteran actor Bruce Campbell is executive producer and host of the reboot of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” NEW YORK (January 2, 2019) – Ripley’s Believe It or Not! has cornered the market on the extraordinary, the death defying, the odd and the unusual. Now, 100 years after Robert L. Ripley launched the brand, the phrase Believe It or Not! is known globally and has come to symbolize how we marvel at the wonders of our world. Travel Channel is rebooting the iconic series, hosted by veteran actor Bruce Campbell (Evil Dead, Burn Notice), with 10 all-new, one-hour episodes that will showcase the most astonishing, real and one-of-a- kind stories. Currently in production, the series will be shot on location at the famed Ripley Warehouse in Orlando, Florida, and will incorporate incredible stories from all parts of the globe — from Brazil to Baltimore. The series is slated to premiere in summer 2019. As part of the 100th anniversary celebration of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, Campbell rang in the new year in Times Square with the New Year’s Eve Ball Drop along with millions of new friends. “As an actor, I’ve always been drawn toward material that is more ‘fantastic’ in nature, so I was eager and excited to partner with Travel Channel and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! on this new show,” said Campbell. -

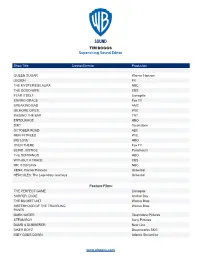

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Feature Films

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production QUEEN SUGAR Warner Horizon LEGION FX THE MYSTERIES/LAURA NBC THE GOOD WIFE CBS FEAR ITSELF Lionsgate SAVING GRACE Fox TV BREAKING BAD AMC GILMORE GIRLS. W.B. RAISING THE BAR TNT ENTOURAGE HBO DIRT Touchstone OCTOBER ROAD ABC MEN IN TREES W.B. BIG LOVE HBO OVER THERE Fox TV BLIND JUSTICE Paramount THE SOPRANOS HBO WITHOUT A TRACE CBS MR. STERLING NBC XENA: Warrior Princess Universal HERCULES: The Legendary Journeys Universal Feature Films: THE PERFECT GAME Lionsgate SURFER, DUDE Anchor Bay THE BUCKET LIST Warner Bros. SISTERHOOD OF THE TRAVELING Warner Bros. PANTS DARK WATER Touchstone Pictures STEAM BOY Sony Pictures DUMB & DUMBERER New Line BIKER BOYZ Dreamworks SKG IGBY GOES DOWN Atlantic Streamline www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production WE WERE SOLDIERS Icon HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES Universal TRIXIE Sand Castle 5 Productions WALKING ACROSS EGYPT Mitchum Entertainment THE END OF VIOLENCE MGM THE LESSER EVIL Moon Dog Productions WASHINGTON SQUARE Hollywood Pictures LOST HIGHWAY October Films DEMON KNIGHT Universal ABOVE THE RIM New Line Cinema BLANK CHECK Disney HOUSE PARTY 3 New Line Cinema THE GLASS SHIELD Miramax DARKMAN III Universal DARKMAN II Universal Television/Cable Movies (Adr Supervisor) AMAZON HIGH Universal Home Ent. ANOTHER MIDNIGHT RUN Universal Television ASSAULT AT WEST POINT Showtime ATTACK OF THE 5’2’’ WOMAN Showtime BLIND JUSTICE HBO Pictures COLOR OF JUSTICE Showtime CONVICTION CBS THE COURTYARD Showtime DARK REFLECTIONS Fox FULL BODY MASSAGE Showtime FULL ECLIPSE HBO Pictures GANG IN BLUE Showtime HERCULES AND THE AMAZON Universal WOMEN HERCULES AND THE LOST KING- Universal DOM HERCULES AND THE CIRCLE OF Universal FIRE www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production HERCULES IN THE UNDERWORLD Universal HERCULES AND THE MAZE OF Universal THE MINOTAUR HERCULES: THE FIGHT FOR Universal Home Ent. -

The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess

−1− CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL ONTARIO REGIONAL COUNCIL CFPL-TV re episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess (CBSC Decision 98/99-0306) Decided June 17, 1999 A. MacKay (Chair), R. Stanbury (Vice-Chair), R. Cohen (ad hoc), P. Fockler, M. Hogarth and M. Ziniak THE FACTS On February 7, 1999, beginning at 4 pm, CFPL-TV (London) aired back-to-back episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess, both of which are tongue-in-cheek action-packed fantasy shows, loosely based in Greek mythology. In the particular episode of Hercules viewed by the Council, the legendary hero travels to a parallel universe where he meets his “evil” twin. The twin is in love with “The Empress”, a provocatively dressed, ruthless and impetuous woman who likes to feel her power and who harbours a desire to conquer the world. The twin is stabbed early on in the episode, leaving the real Hercules to take his place and attempt to set things right. His efforts to do so force him to take on Aries, the God of War, in battle, to escape from a large dragon snake and to fight the Empress herself. Not surprisingly, there are many scenes depicting violent acts in the program, but most of these are presented as acrobatic and often as humourous moments. On the few occasions in which any blood is shown, the scenes do not include the actual infliction of the wound or the physical wound itself, but rather blood on peripheral objects to suggest the wound. Examples include the filming of “blood” on a rock next to which lies the unconcious twin and, later in the show, the knife which killed the evil twin is shown covered in blood. -

E Ogil in English: Literature

“WE’RE ALL IN SOMEBODY ELSE’S HEAD”: CONSTRUCTING HISTORY AND IDENTITY IN XENA A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree A3 Master of Arts E_OGiL In English: Literature by Rvann Mackenzie Lannan San Francisco. California January 2018 Copyright by Rvann Mackenzie Lannan 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read “’We’re all in somebody else’s head’: Constructing History and Identity in Xena ” by Ryann Mackenzie Lannan, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English: Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Green, Ph.D. Professor “We’re all in somebody else’s head”: Constructing History and Identity in Ryann Mackenzie Lannan San Francisco, California 2017 My thesis analyzes the construction of history and identity in the pop-culture television show Xena: Warrior Princess ( XWP ). I argue that the implicit allegory of XWP shows us that history and identity exist as interpretable and revisable narratives. I use the character Gabrielle’s chronicling of Xena’s adventures to show how historical narratives are consciously constructed by historians to tell one specific version of events. I then use her mediation of the major characters to depict how historians also construct the characters of history. I then show that similarly, all people read and are read by others, and that these readings influence identity construction. XWP shows that identity originates outside the self and is a product of constant dialog between the self and the other. -

Warrior Princess (XSTT) Lesbian Internet Fans

Understanding Lesbian Fandom: A Case Study of the Xena: Warrior Princess (XSTT) Lesbian Internet Fans by Rosalind Maria Hanmer A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY American and Canadian Studies The University of Birmingham December 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis is written to promote and pursue an understanding of lesbian fandom and its function on the Internet. It will demonstrate how a particular television text Xena: Warrior Princess (X: WP) and a dedicated online fandom „xenasubtexttalk‟ (XSTT) of diverse lesbian fan membership gained empowerment and agency through their fan practices. Since the screening of the television fantasy series X: WP (1995-2001), there has been a marked increase in academic enquiry into lesbian fan culture on the Internet. This thesis contributes to the lesbian spectatorship of fandom with a specific interest in online fandom. This research suggests there are many readings of X: WP and the dedicated websites set up to discuss the series have increased during and post the series broadcast period. -

Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES “Evil is always waiting in the shadows and only one man would rise to stand against it.” Those are the words uttered about Ash Williams, who after three decades of avoiding responsibility, maturity and the terrors of the evil dead returns on Halloween night in “Ash vs Evil Dead,” the long awaited follow-up to the classic Evil Dead series. The 10- episode half-hour series follows Ash the stock boy, aging lothario and chainsaw-handed monster hunter as he is forced to face his demons, both personal and literal when a Deadite plague threatens to destroy all of mankind. Destiny, it turns out, has no plans to release the unlikely hero from “Evil’s” grip. Bruce Campbell reprises his role as Ash Williams and is joined by Lucy Lawless as Ruby, a mysterious figure who believes Ash is the cause of the Evil outbreaks; Ray Santiago as Pablo Simon Bolivar, an idealistic immigrant who becomes Ash’s loyal sidekick; Dana DeLorenzo as Kelly Maxwell, a moody wild child trying to outrun her past; and Jill Marie Jones as Amanda Fisher, a disgraced Michigan State Trooper set to find our anti-hero Ash and prove his responsibility in the grisly murder of her partner. Premiering on Halloween night, October 31st 2015, the series is executive produced by Sam Raimi, Rob Tapert and Bruce Campbell, the original filmmakers; and Craig DiGregorio who serves as executive producer and showrunner. Fans have been clamoring for more Evil Dead for years, according to Campbell and Raimi—as much as they loved the 2013 remake, it didn’t contain fan-favorite character Ashley J. -

Retorica Da Midia

Os pergaminhos de Amphipolis 1 Aforismos meta narrativos sobre a saga da Princesa Guerreira 2 Marcelo Bolshaw GOMES Resumo O presente texto detalha e analisa a releitura meta narrativa de diferentes mitologias realizadas pelo seriado de TV Xena, a princesa Guerreira. O objetivo é identificar algumas características narrativas: os universos múltiplos, a morte, a vida sem inimigos. Conclui-se que o mito das moiras, representando as estruturas narrativas do tempo, se tornou o antagonista do anti-herói pós-moderno. Palavras chave: Comunicação midiática. Estudos narrativos da televisão. Introdução A 'Jornada do Herói' como processo iniciático é uma viagem eminentemente masculina, refletindo um contexto cultural patriarcal. 'Iniciação' é um rito de passagem, em que um jovem torna-se membro adulto de uma determinada comunidade. Nas lendas que expressam esses processos, os heróis são sempre homens, enfrentando situações masculinas: lutando pela justiça e pela verdade. As mulheres, nessas estórias, correspondem ao Sagrado Feminino ou 'anima narrativa', isto é, à representação projetada dos valores femininos do narrador (mediação entre autor e leitor) no interior da narrativa. Com isso, elas, ou são meras coadjuvantes, sequestradas pelo dragão e resgatadas para o casamento alquímico final; e/ou então se associam com o mal e seus vilões, dificultando a vida do herói. Há também estórias em que a mulher é a protagonista em um universo com valores masculinos, como a estória de Joana D'Arc, por exemplo. Por isso, contar uma estória iniciática (uma jornada heroica) em que a mulher e os valores femininos sejam os protagonistas e o aspecto cognitivo masculino seja minimizado sempre foi um desafio narrativo presente para vários contares de estórias. -

Warrior Princess Brian H

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 When Discourses Collide: Hegemony, Domestinormativity, and the Active Audience in Xena: Warrior Princess Brian H. Myers Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WHEN DISCOURSES COLLIDE: HEGEMONY, DOMESTINORMATIVITY, AND THE ACTIVE AUDIENCE IN XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS By BRIAN H. MYERS A Thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Brian H. Myers defended on March 26, 2008. Leigh Edwards Professor Directing Thesis Jennifer Proffitt Committee Member Caroline Joan Picart Committee Member Approved: R.M. Berry, Chair, Department of English Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to my parents, who may not always understand my obsessions but have always encouraged me to pursue them, and to Nanny and Grandpa, who I hope will look down on this with pride. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As is the case with any work of this size, more people went into it than can possibly be included on a title page. My first thanks, of course, must go to the members of my thesis committee, whose advice and comments frequently saved me from myself in both the writing of this thesis and in the grander realm of life. -

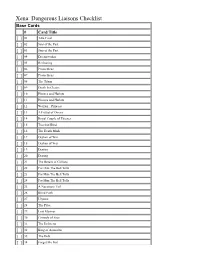

Xena: Dangerous Liaisons Checklist

Xena: Dangerous Liaisons Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Title Card [ ] 02 Sins of the Past [ ] 03 Sins of the Past [ ] 04 Dreamworker [ ] 05 Reckoning [ ] 06 Prometheus [ ] 07 Prometheus [ ] 08 The Titans [ ] 09 Death In Chains [ ] 10 Hooves and Harlots [ ] 11 Hooves and Harlots [ ] 12 Warrior…Princess [ ] 13 A Fistful of Dinars [ ] 14 Royal Couple of Thieves [ ] 15 Ties that Bind [ ] 16 The Death Mask [ ] 17 Orphan of War [ ] 18 Orphan of War [ ] 19 Destiny [ ] 20 Destiny [ ] 21 The Return of Callisto [ ] 22 For Him The Bell Tolls [ ] 23 For Him The Bell Tolls [ ] 24 For Him The Bell Tolls [ ] 25 A Necessary Evil [ ] 26 Blind Faith [ ] 27 Ulysses [ ] 28 The Price [ ] 29 Lost Mariner [ ] 30 Comedy of Eros [ ] 31 The Deliverer [ ] 32 King of Assassins [ ] 33 The Debt [ ] 34 Forget Me Not [ ] 35 Sacrifice [ ] 36 Sacrifice [ ] 37 Adventures In the Sin Trade [ ] 38 Adventures In the Sin Trade [ ] 39 A Family Affair [ ] 40 A Family Affair [ ] 41 Paradise Found [ ] 42 Between the Line [ ] 43 Between the Line [ ] 44 Crusader [ ] 45 Past Imperfect [ ] 46 Takes One to Know One [ ] 47 The Ides of March [ ] 48 The Ides of March [ ] 49 Fallen Angel [ ] 50 Fallen Angel [ ] 51 Succession [ ] 52 Them Bones, Them Bones [ ] 53 Them Bones, Them Bones [ ] 54 Purity [ ] 55 Seeds of Faith [ ] 56 Lyre, Lyre, Hearts on Fire [ ] 57 God Fearing Child [ ] 58 God Fearing Child [ ] 59 God Fearing Child [ ] 60 Eve [ ] 61 Haunting of Amphipolis [ ] 62 Heart of Darkness [ ] 63 The Rheingold [ ] 64 Send in the Clones [ ] 65 You Are There [ ] 66 Path of Vengeance -

The Internet World of Fan Fiction

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The Internet World of Fan Fiction Melissa Jean Herzing Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1046 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Melissa J. Herzing 2005 All Rights Reserved THE INTERNET WORLD OF FAN FICTION A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Melissa J. Herzing B.A., Indiana University of Pennsylvania 1990 M.A., Indiana University of Pennsylvania 1991 Director: Dr. Elizabeth Hodges Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2005 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my partner, Christine, for her unbelievable support and encouragement. Were it not for the topic of my thesis, we might not have met. Her patience and understanding as well as her devotion and dedication to my work have been both inspirational and motivational to me throughout my educational experience. I would also like to thank my best friend, Tausha. She has been extremely supportive of me in my return to school. And throughout my experience in graduate school, my family has been behind me one hundred percent. I appreciate all that everyone has done for me. -

Season Two- Production Biographies

-SEASON TWO- PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES SAM RAIMI (EXECUTIVE PRODUCER) Sam Raimi has directed one the industry’s most successful film franchises ever—the blockbuster Spider-Man trilogy, which has grossed $2.5 billion at the global box office. All three films reside in the industry’s top 25 highest grossing titles of all time. In addition to the franchise’s commercial success, Spider-Man (2002) won that year’s People’s Choice Award as Favorite Motion Picture, earned a pair of Oscar® nominations (for VFX and Best Sound) and also collected two Grammy® nominations (for Best Score and Chad Kroeger’s song, “Hero”). The sequel, Spider-Man 2 (2004) won the Academy Award® for Best Visual Effects (with two more nominations, Best Sound and Sound Editing) and two BAFTA nominations (for VFX and Best Sound), among dozens of other honors. Most recently, Raimi is known for directing Oz the Great and the Powerful, a commanding prequel to one of Hollywood’s most beloved stories. Grossing nearly a quarter of a billion dollars at the worldwide box office, Oz has also been elected for awards across the board, including a nomination at the People’s Choice Awards for Favorite Family Movie, and winning Film Music at the BMI Film & TV Awards. Apart from creating one of Hollywood’s landmark film series, Raimi’s eclectic resume includes the gothic thriller The Gift, starring Cate Blanchett, Hilary Swank, Keanu Reeves, Greg Kinnear, and Giovanni Ribisi; the acclaimed suspense thriller A Simple Plan, which starred Bill Paxton, Billy Bob Thornton, and Bridget Fonda (for which Thornton earned an Academy Award® nomination for Best Supporting Actor and Scott B.