Rewriting Xena: Warrior Princess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

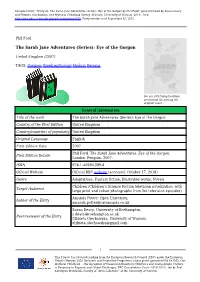

OMC | Data Export

Amanda Potter, "Entry on: The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon by Phil Ford", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/550. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Phil Ford The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon United Kingdom (2007) TAGS: Gorgons Greek mythology Medusa Perseus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Country/countries of popularity United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2007 Phil Ford. The Sarah Jane Adventures: Eye of the Gorgon. First Edition Details London: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-1-40590-399-8 Official Website Official BBC website (accessed: October 17, 2018) Genre Adaptations, Fantasy fiction, Illustrated works, Novels Children (Children’s Science Fiction television novelization, with Target Audience large print and colour photographs from the television episodes) Amanda Potter, Open University, Author of the Entry [email protected] Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal Title Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29q2t238 Journal UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal, 8(2) Author Abidia, Layla Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/M482030778 Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Layla Abidia University of California, Merced Author Notes: Questions and comments can be address to [email protected] 1 Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Abstract Hmong American men and women face social and cultural struggles where they are expected to adhere to Hmong requirements of gender handed down to them by their parents, and the expectations of the country they were born in. The consequence of these two expectations of contrasting values results in stress for everyone involved. Hmong parents are stressed from not having a secure hold on their children in a foreign environment, with no guarantee that their children will follow a “traditional” route. Hmong American men are stressed from growing up in a home environment that grooms them to be a focal point of familial attention based on gender, with the expectation that they will eventually be responsible for an entire family; meanwhile, they are living in this American national environment that stresses that the ideal is that gender is irrelevant in the modern world. Hmong American women are stressed and in turn hold feelings of resentment that they are expected to adhere to traditional familial roles by their parents in addition to following a path to financial success the same as men. -

Xena and Buffy

Frances Early, Kathleen Kennedy, eds.. Athena's Daughters: Television's New Women Warriors. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003. 175 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8156-2968-9. Reviewed by Robin Riley Published on H-Peace (May, 2004) It is a strange experience to be reading and each represent, at least, "a girl-power hero--a writing about "television's new women warriors" young, hip, and alluring portrayal of female au‐ when television and the nation have actual wom‐ tonomy that offers an implicit contrast to and cri‐ en warriors with whom we have recently ob‐ tique of the second-wave feminist generation that sessed. Could it be that the presence of fctitious came of age in the 1960s and 1970s" (p. 3). The women warriors helped to conceptually prepare question of whether or not these characters or se‐ us for Jessica Lynch? ries represent a move towards female just war‐ Fans of Xena, Warrior Princess (as the au‐ riors, contain critiques of war, or are attempting thors say, hereafter XWP) and Buffy the Vampire to subvert traditional ways of thinking about gen‐ Slayer (not similarly acronymed) will enjoy this der and war, appears and disappears across the collection. Athena's Daughters is flled with plot collection's essays. references to episodes from the Xena and Buffy Frances Early and Kathleen Kennedy are dis‐ "verses," as well as two essays from authors fo‐ mayed at this turn toward "girl power heroes" cusing on the La Femme Nikita and Star Trek Voy‐ with its accompanying de-politicization of gender ager_ series. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

Bad Girls to the Rescue an Exhibition of Feminist Art from the 1990S Has Much to Teach Us Today

PERSPECTIVES Bad Girls to the Rescue An exhibition of feminist art from the 1990s has much to teach us today By Maura Reilly n my new book Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics did just that—and within a lineage worth revisiting as the present of Curating (Thames & Hudson), I devoted a chapter to adjusts for oversights of the past. I exhibitions that have lingered in the historical record for their Though most commonly associated with a notorious run at the commitment to “Resisting Masculinism and Sexism.” As what New Museum in 1994—in a tradition that would directly influence constitutes sexual prejudice continues to evolve, it’s imperative “Trigger” decades later—the first iteration of a series of shows titled that curators continually query and challenge the gender norms “Bad Girls” was organized separately the year before for the Institute by which we are all confined. “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a of Contemporary Arts in London (followed by a presentation at the Weapon,” a recent exhibition at the New Museum in New York, Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow). Curated by Kate Bush, NEW YORK. ART, NEW MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY FRED SCRUTON/COURTESY THIS PAGE: RIGHTS SOCIETY/ARS ARTIST OPPOSITE: ©DEBORAH KASS/PHOTO COURTESY 32 ARTNEWS Perspectives.indd 1 2/16/18 5:12 PM Emma Dexter, and Nicola White, the exhibition celebrated a new spirit of playfulness, tactility, and perverse humor in the work of six British and American women artists: Helen Chadwick, Dorothy Cross, Nicole Eisenman, Rachel Evans, Nan Goldin, and Sue Williams—each of whom was represented by several works. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

REALLY BAD GIRLS of the BIBLE the Contemporary Story in Each Chapter Is Fiction

Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page i Praise for the Bad Girls of the Bible series “Liz Curtis Higgs’s unique use of fiction combined with Scripture and modern application helped me see myself, my past, and my future in a whole new light. A stunning, awesome book.” —R OBIN LEE HATCHER author of Whispers from Yesterday “In her creative, fun-loving way, Liz retells the stories of the Bible. She deliv - ers a knock-out punch of conviction as she clearly illustrates the lessons of Scripture.” —L ORNA DUECK former co-host of 100 Huntley Street “The opening was a page-turner. I know that women are going to read this and look at these women of the Bible with fresh eyes.” —D EE BRESTIN author of The Friendships of Women “This book is a ‘good read’ directed straight at the ‘bad girl’ in all of us.” —E LISA MORGAN president emerita, MOPS International “With a skillful pen and engaging candor Liz paints pictures of modern sit u ations, then uniquely parallels them with the Bible’s ‘bad girls.’ She doesn’t condemn, but rather encourages and equips her readers to become godly women, regardless of the past.” —M ARY HUNT author of Mary Hunt’s Debt-Proof Living Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page ii “Bad Girls is more than an entertaining romp through fascinating charac - ters. It is a bona fide Bible study in which women (and men!) will see them - selves revealed and restored through the matchless and amazing grace of God.” —A NGELA ELWELL HUNT author of The Immortal “Liz had me from the first paragraph. -

Write-Ins Race/Name Totals - General Election 11/03/20 11/10/2020

Write-Ins Race/Name Totals - General Election 11/03/20 11/10/2020 President/Vice President Phillip M Chesion / Cobie J Chesion 1 1 U/S. Gubbard 1 Adebude Eastman 1 Al Gore 1 Alexandria Cortez 2 Allan Roger Mulally former CEO Ford 1 Allen Bouska 1 Andrew Cuomo 2 Andrew Cuomo / Andrew Cuomo 1 Andrew Cuomo, NY / Dr. Anthony Fauci, Washington D.C. 1 Andrew Yang 14 Andrew Yang Morgan Freeman 1 Andrew Yang / Joe Biden 1 Andrew Yang/Amy Klobuchar 1 Andrew Yang/Jeremy Cohen 1 Anthony Fauci 3 Anyone/Else 1 AOC/Princess Nokia 1 Ashlie Kashl Adam Mathey 1 Barack Obama/Michelle Obama 1 Ben Carson Mitt Romney 1 Ben Carson Sr. 1 Ben Sass 1 Ben Sasse 6 Ben Sasse senator-Nebraska Laurel Cruse 1 Ben Sasse/Blank 1 Ben Shapiro 1 Bernard Sanders 1 Bernie Sanders 22 Bernie Sanders / Alexandria Ocasio Cortez 1 Bernie Sanders / Elizabeth Warren 2 Bernie Sanders / Kamala Harris 1 Bernie Sanders Joe Biden 1 Bernie Sanders Kamala D. Harris 1 Bernie Sanders/ Kamala Harris 1 Bernie Sanders/Andrew Yang 1 Bernie Sanders/Kamala D. Harris 2 Bernie Sanders/Kamala Harris 2 Blain Botsford Nick Honken 1 Blank 7 Blank/Blank 1 Bobby Estelle Bones 1 Bran Carroll 1 Brandon A Laetare 1 Brian Carroll Amar Patel 1 Page 1 of 142 President/Vice President Brian Bockenstedt 1 Brian Carol/Amar Patel 1 Brian Carrol Amar Patel 1 Brian Carroll 2 Brian carroll Ammor Patel 1 Brian Carroll Amor Patel 2 Brian Carroll / Amar Patel 3 Brian Carroll/Ama Patel 1 Brian Carroll/Amar Patel 25 Brian Carroll/Joshua Perkins 1 Brian T Carroll 1 Brian T. -

3.50 Story by Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti

http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl 1. PAINKILLER JANE #1 Price: $3.50 STORY BY JOE QUESADA AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI; WRITTEN BY JIMMY PALMIOTTI; ART BY LEE MODER; COVER ART BY RON ADRIAN, STJEPAN SEJIC, GEORGES JEANTY, AND AMANDA CONNER Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! Picking up from the explosive events of issue #0, PKJ #1 hits the ground running as Jane faces international terrorists and the introduction of a brand new character - "The Infidel" who will change her world forever! Featruing cover art by Ron (Supergirl, RED SONJA) Adrian, Georges (Buffy) Jeanty, Amanda (Supergirl) Conner, and Stjepan (Darkness) Sejic! Find out for yourself why reviewers have described Jane and her creators as "Jimmy Palmiotti has a sick, twisted imagination, and he really cut it loose here. But the book really works because Lee Moder draws the hell out of it, depicting every gruesome moment with grisly adoration for the script." (Marc Mason, ComicsWaitingRoom.com) FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER BLACK AND WHITE SKETCH INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE RON ADRIAN NEGATIVE ART INCENTIVE COVER! FANS! ASK YOUR LOCAL RETAILER ABOUT THE AMANDA CONNER VARIANT SIGNED BY AMANDA CONNER AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI! 2. PAINKILLER JANE #1 - RON ADRIAN COVER AVAILABLE AS A BLOOD RED FOIL Price: $24.95 Jane is back! The creative team of Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti and Lee Moder return for an all-new Painkiller Jane event! -

'Ripley's Believe It Or

For Immediate Release: BELIEVE IT OR NOT, TRAVEL CHANNEL GREENLIGHTS THE REBOOT OF THE ICONIC ‘RIPLEY’S BELIEVE IT OR NOT!’ HOSTED BY ACTOR BRUCE CAMPBELL Veteran actor Bruce Campbell is executive producer and host of the reboot of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” NEW YORK (January 2, 2019) – Ripley’s Believe It or Not! has cornered the market on the extraordinary, the death defying, the odd and the unusual. Now, 100 years after Robert L. Ripley launched the brand, the phrase Believe It or Not! is known globally and has come to symbolize how we marvel at the wonders of our world. Travel Channel is rebooting the iconic series, hosted by veteran actor Bruce Campbell (Evil Dead, Burn Notice), with 10 all-new, one-hour episodes that will showcase the most astonishing, real and one-of-a- kind stories. Currently in production, the series will be shot on location at the famed Ripley Warehouse in Orlando, Florida, and will incorporate incredible stories from all parts of the globe — from Brazil to Baltimore. The series is slated to premiere in summer 2019. As part of the 100th anniversary celebration of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, Campbell rang in the new year in Times Square with the New Year’s Eve Ball Drop along with millions of new friends. “As an actor, I’ve always been drawn toward material that is more ‘fantastic’ in nature, so I was eager and excited to partner with Travel Channel and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! on this new show,” said Campbell. -

The Warriors Princess Free

FREE THE WARRIORS PRINCESS PDF Barbara Erskine | 480 pages | 17 Mar 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007174294 | English | London, United Kingdom Thus, the Adventures of Mum and Princess was created Join us on an FB Live chat today at The Warriors Princess. Khutulun deserves her own place in history However, even among the standards of all those powerful Mongol women, Khutulun writes a distinct place for herself. Born aboutKhutulun, was the great-great granddaughter of Genghis Khan and a legend in her own right. Unlike her cousin, the emperor Kublai Khan, who relished the comfort and luxuries of the Chinese court, Khutulun chose the rough, nomadic lifestyle — the traditional Mongol way of life. Benevolently imaged as beautiful, and much sought after by men, Khutulun was a woman of extraordinary strength. She mastered the Mongol arts of horse-riding, archery, and wrestling where she eventually became the champion wrestler whom no man could defeat. She also transcended at the cardinal Mongol vocation of warfare. However, it is important to note that it was not unusual for Mongolians to see women on horses or dealing with bows and arrows, but what made Khutulun an anomaly was her excellence, the refinement of her skills among many of her likes. Her father, Qaidu Khan, awarded her a gergee a medal of office that stated the power of the holder as an acknowledgement of her power and independence. She is the only woman recorded to have received that, as it was an authority usually The Warriors Princess for men. Khutulun outperformed all her fourteen brothers since a very early age.