What Is EU Public Health and Why? Explaining the Scope and Organization of Public Health in the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 24–26, 2021 2

SCIENCE · INNOVATION · POLICIES WORLD HEALTH SUMMIT BERLIN, GERMANY & DIGITAL OCTOBER 24–26, 2021 2 “No-one is safe from COVID-19; “All countries have signed up to Universal no-one is safe until we are all Health Coverage by 2030. But we cannot safe from it. Even those who wait ten years. We need health systems conquer the virus within their that work, before we face an outbreak own borders remain prisoners of something more contagious than within these borders until it is COVID-19; more deadly; or both.” conquered everywhere.” ANTÓNIO GUTERRES Secretary-General, United Nations FRANK-WALTER STEINMEIER Federal President, Germany “We firmly believe that the “All pulling together—this must rights of women and girls be the hallmark of the European are not negotiable.” Health Union. I believe this can NATALIA KANEM be a test case for true global Executive Director, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) health compact. The need for leadership is clear and I believe the European Union must as- sume this responsibility.” “The lesson is clear: a strong health URSULA VON DER LEYEN system is a resilient health system. Health President, European Commission systems and preparedness are not only “Governments of countries an investment in the future, they are the that are doing well during foundation of our response today.” the pandemic have not TEDROS ADHANOM GHEBREYESUS Director-General, World Health Organization (WHO) only shown political leader- ship, but also have listened “If we don’t address the concerns and to scientists and followed fears we will not do ourselves a favor. their recommendations.” In the end, it is about how technology SOUMYA SWAMINATHAN Chief Scientist, World Health can be advanced as well as how Organization (WHO) we can make healthcare more human.” BERND MONTAG President and CEO, Siemens Healthineers AG, Germany “The pandemic has brought to light the “Academic collabo ration is importance of digital technologies and in place and is really a how it can radically bridging partnership. -

Stella Kyriakides: EU Commissioner for Health

Stella Kyriakides: EU Commissioner for Health Alberto Costa / 2 November 2020 When Stella Kyriakides took on the post of EU Health Commissioner in September 2019, Europe’s cancer community knew they could trust her to fight their cause. Within months she was launching a public consultation on Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. Then came COVID. Alberto Costa asked her how her experience as a breast cancer survivor and patient advocate shaped her approach to her new role and how she is coping with the demands of responding to a major public health crisis while still delivering on the expectations of the cancer community. Cancer World: You were still becoming familiar with your new office at the Berlaymont in Brussels when the COVID-19 pandemic exploded. How did you respond? Stella Kyriakides: In Greek, there is a saying: “In difficult situations, you just roll up your sleeves and get the work done.” There was no option but to do everything to rise to the challenge of the greatest public health crisis in memory. Quickly getting a grasp of the issues at hand, ensuring we have the right expertise in place, connecting the dots to our Member States and European Parliament, and finding pragmatic, concrete and workable solutions as quickly as possible in a calm and effective way. The COVID-19 crisis has affected the lives of countless citizens and businesses around the globe. As European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, it is my responsibility to ensure that we do everything we can to protect public health. It is important to be prepared for any eventuality at all times, and be ready to react swiftly. -

A Guide to the New Commission

A guide to the new Commission allenovery.com 2 A guide to the new Commission © Allen & Overy LLP 2019 3 A guide to the new Commission On 10 September, Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen announced the new European Commission. There were scarcely any leaks in advance about the structure of the new Commission and the allocation of dossiers which indicates that the new Commission President-elect will run a very tight ship. All the Commission candidates will need approval from the European Parliament in formal hearings before they can take up their posts on 1 November. Von der Leyen herself won confirmation in July and the Spanish Commissioner Josep Borrell had already been confirmed as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Policy and Security Policy. The new College of Commissioners will have eight Vice-Presidents technological innovation and the taxation of digital companies. and of these three will be Executive Vice-Presidents with supercharged The title Mrs Vestager has been given in the President-elect’s mission portfolios with responsibility for core topics of the Commission’s letter is ‘Executive Vice-President for a Europe fit for the Digital Age’. agenda. Frans Timmermans (Netherlands) and Margrethe Vestager The fact that Mrs Vestager has already headed the Competition (Denmark), who are incumbent Commissioners and who were both portfolio in the Juncker Commission combined with her enhanced candidates for the Presidency, were rewarded with major portfolios. role as Executive Vice-President for Digital means that she will be Frans Timmermans, who was a Vice-President and Mr Junker’s a powerful force in the new Commission and on the world stage. -

The Eu's New Commission: Digital Policy in the Limelight

Policy Papers and Briefs - 13, 2019 THE EU’S NEW COMMISSION: DIGITAL POLICY IN THE LIMELIGHT Stephanie Borg Psaila Summary • The work of the new European Commission (EC) offi- • The EC President also wants to see a more balanced cially started in December 2019. Leading the work approach to how data is used: allowing the flow and use is a set of political guidelines issued by incoming EC of data for the benefit of innovation and market growth, President Ursula von der Leyen, focusing on climate, while adhering to strong privacy, security, and ethical technology, and demography. standards. • In relation to technology and digital policy, there are ten • Across other key areas, the EC President plans to make key areas of relevance, including artificial intelligence Europe a tech sovereign by taking the lead in stand- (AI) and data, which the EC President sees as the key ard-setting, and investing in the tech industry. ingredients that can help solve societal problems. • Although the guidelines will be the EC’s compass for the • Among the most anticipated policy measures is one that next five years, the implications go beyond European relates to AI: ‘In my first 100 days in office, I will put -for shores. ward legislation for a coordinated European approach on the human and ethical implications of AI.’ December 2019 Introduction: The Commission’s digital policy priorities for the next five years The work of the new European Commission (EC) officially including artificial intelligence (AI) and data, which she started in December, after a delay in vetting procedures sees as the key ingredients that can help solve soci- (and partially due to Brexit). -

Valérie Hayer Member of the European Parliament Brussels, 11

Valérie Hayer Brussels, 11 March 2020 Member of the European Parliament Ms. Ursula von der Leyen President European Commission Rue de la Loi / Wetstraat 200 1049 Brussels Belgium Dear President, On behalf of the Renew Europe Group’s French delegation, I ask you and the coronavirus response team to take all the appropriate budgetary measures to ensure a coordinated European response to the health, economic and social impacts caused by the coronavirus outbreak in all Member States of the European Union (EU). In this regard, I welcome the Corona Response Investment Initiative aiming at mobilising 7.5 billion of euros unspent for the cohesion policy. In addition, I want to raise your attention that more than 4 billion of euros are also available for unforeseen events and crises in this year budget. As this situation puts high pressure on our European businesses, economy and workers, we should use the EU budget flexibilities to alleviate economic losses and reinforce sectors and enterprises at risk, enabling the European Union and its businesses to cope with unforeseen sanitary crises in the future at the same time. Consequently, I urge you to make a proposal for the modification of the Council Regulation (EU) 2016/369 of 15 March 2016 on the provision of emergency support within the Union in order to extend its scope for providing European businesses and sectors negatively and significantly impacted by an epidemic with a budgetary support to avoid their collapse and job losses, but also to prepare them for any future crisis. If such a modification cannot be considered, I ask you to propose a new Regulation based on the Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which states that the Union may grant financial assistance “where a Member State is in difficulties or is seriously threatened with severe difficulties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control”. -

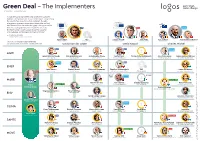

The Implementers 27 November – 31 December 2019

Green Deal – The Implementers 27 November – 31 December 2019 ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities Renew from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be EPP S&D Europe the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission Bjoern Seibert TBD Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle François Roux Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans will coordinate the work on the European Green Deal. Ursula von der Leyen David Sassoli Charles Michel ECR EPP Renew Europe AGRI Janusz Wojciechowski Maciej Golubiewski Jerzy Bogdan Plewa Norbert Lins Tereza Pinto De Rezende Jari Juhani Leppä Sanna-Helena Fallenius Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General AGRI Committee Chair AGRI Secretariat Minister of Agriculture Permanent Representation Renew ECR Europe ENER Kadri Simson Stefano Grassi Ditte Juul-Jørgensen Zdzisław Krasnodębski TBD Sanna Ek-Husson ITRE Secretariat S&D Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General ITRE Acting Committee Chair Permanent Representation with ENVI with ENVI Pascal Renew Sara Blau Canfin Europe MARE Greens/EFA Bernhard Friess Chris Davies Claudio Quaranta Riitta Rahkonen -

Is Populism a Problem

Is populism a problem STRASBOURG 8 10 NOVEMBER PROGRAMME #CoE_WFD The world Forum for democracy is placed under the high patronnage of Emmanuel Macron, President of the French Republic 2 Populism may take many forms and vary in defnition, but it is almost always a symptom of democratic malaise. Democracy requires public trust and an institutional balance, enabling fair political competition, the alternation of power, and constructive political negotiation. This trust is being rapidly eroded. Many citizens now believe that the actors of liberal democracy – in particular traditional political parties, and the media, do not serve their interests. They feel that liberal democracy has failed them and they are looking for new opportunities for political participation. This sentiment of powerlessness and desperation provides fertile ground for populism. Some populists claim to make marginalised voices matter by formulating more equitable, fair, and sustainable policies. Others hijack the political debate with an aggressive, divisive rhetoric and attacks on liberal values. They claim to embrace democracy – but not of the liberal kind. They curb political pluralism and freedom of expression, and undermine the judiciary, media and multilateral institutions that can hold them accountable. The liberal democratic consensus was born from the immense sufering of the Second World War. Mass political parties and the mass media were the guardians of liberal democracy in the industrial era. We need to profoundly rethink democracy in the age of the internet, big data, and social media and bring citizens to the heart of policy-making. The World Forum for Democracy 2017 will enable political leaders, activists and change-makers from around the world to share solutions that can help stop authoritarian populism, now a pathology of democracy, from becoming the norm. -

Global Health Summit 21 May 2021

Global Health Summit 21 May 2021 12:00-13:00 PRE-SUMMIT (CEST) Welcome addresses by: 12:00-12:03 Mario Draghi, President of the Council of Ministers of the Italian Republic 12:03-12:06 Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission 12:06-12:12 Professor Peter Piot, Professor Silvio Brusaferro, Professor Victor Dzau, Professor Yee-Sin Leo, and Professor John Nkengasong (co-chairs of the High-Level Scientific Panel) 12:12-12:16 Professor Elizabeth Adams (President of the European Federation of Nurses Associations) 12:16-12:20 Stefania Burbo (Civil 20 Chair) 12:20-12:28 Rt. Hon. Helen Clark and H.E. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (co-chairs of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response) 12:28-12:36 Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam and Professor Lawrence Summers (co-chairs of the G20 High Level Independent Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response) 12:36-12:40 Professor Thomas Mettenleiter and Professor Wanda Markotter (co-chairs of the One Health High-Level Expert Panel) 12:40-12:44 Professor Mario Monti (chair of the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development) 12:44-12:48 Sir Patrick Vallance (UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser and Chair of the Pandemic Preparedness Partnership) 12:48-12:52 Bill Gates (co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) 12:52-12:57 Stella Kyriakides (Health and Food Safety Commissioner), Paolo Gentiloni (Economy Commissioner), Janez Lenarčič (Crisis Management Commissioner), Jutta Urpilainen (International Partnerships Commissioner) -

The Von Der Leyen Commission: an Overview

Briefing November 2019 The von der Leyen Commission: an overview This note provides an overview of this new Commission, which will operate until November 2024. It covers the composition of the von der Leyen team, their political affiliations, the political programme, and some of the changes in structure and modus operandi. It then goes into more detail on the Commissioners of relevance for EuroCommerce and the retail and wholesale sector. The Commission is expected to start working on December 1. The Commission’s team The Commission is made up as follows: Ursula von der Leyen (DE, EPP): President 3 Executive Vice-Presidents Frans Timmermans (NL, S&D): Executive Vice-President - European Green Deal & Climate Action Margrethe Vestager (DK, Renew Europe): Executive Vice-President Europe Fit For the Digital Age & Competition Valdis Dombrovskis (LV, EPP): Executive Vice-President for an Economy That Works For People & Financial Services 5 Vice-Presidents Věra Jourová (CZ, Renew Europe): Vice-President Values and Transparency Dubravka Šuica (HR, EPP): Vice-President Democracy and Demography Margaritis Schinas (EL, EPP): Vice-President Promoting Our European Way of Life Maroš Šefčovič (SK, S&D): Vice-President for Interinstitutional Relations and Foresight Josep Borrell (ES, S&D): High-Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy 18 Commissioners Johannes Hahn (AT, EPP): Budget and Administration Didier Reynders (BE, Renew Europe): Justice Mariya Gabriel (BG, EPP): Innovation and Youth Stella Kyriakides (CY, EPP): Health -

Green Deal – the Implementers 1 January – 30 June 2020

Green Deal – The Implementers 1 January – 30 June 2020 ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities Renew from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be EPP S&D Europe the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission Bjoern Seibert Ilze Juhansone Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle François Roux Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans will coordinate the work on the European Green Deal. Ursula von der Leyen David Sassoli Charles Michel ECR EPP EPP AGRI Janusz Wojciechowski Maciej Golubiewski Maria Angeles Benitez Salas Norbert Lins Tereza Pinto De Rezende Marija Vučković Jakša Petrić Commissioner Head of Cabinet Acting Director General AGRI Committee Chair AGRI Secretariat Minister of Agriculture Permanent Representation Renew EPP EPP Europe ENER Kadri Simson Peter Traung Tomislav Ćorić Željko Krevzelj Stefano Grassi Ditte Juul-Jørgensen Cristian-Silviu Bușoi Minister of Environmental S&D Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General ITRE Committee Chair ITRE Acting Secretariat Protection and Energy Permanent Representation EPP Greens/EFA MOVE Adina-Ioana Vălean Walter Goetz Henrik -

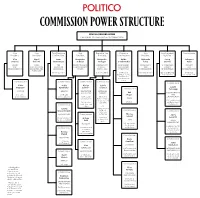

Commission Power Structure

News September 12, 2019 Page 6 COMMISSION POWER STRUCTURE URSULA VON DER LEYEN PRESIDENT OF THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION Vice Vice First Executive Vice Executive Vice Executive Vice Vice President/ Commissioner President President Vice President President President Vice President President High Rep. Věra Maroš Frans Margaritis Margrethe Valdis Dubravka Josep Johannes Jourová Šefčovič Timmermans Schinas Vestager Dombrovskis Šuica Borrell Hahn VALUES INTER- THE PROTECTING OUR A EUROPE FIT AN ECONOMY DEMOCRACY A STRONGER BUDGET AND INSTITUTIONAL EUROPEAN EUROPEAN WAY FOR THE THAT WORKS AND EUROPE AND TRANSPARENCY RELATIONS AND GREEN DEAL OF LIFE DIGITAL AGE FOR PEOPLE DEMOGRAPHY IN THE WORLD ADMINISTRATION FORESIGHT DG Climate Action DG Competition DG Financial DG Communication European External DG Budget Stability, Financial Action Service and four other DGs Services and Capital Markets Union Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Didier Stella Mariya Sylvie Reynders Kyriakides* Gabriel** Goulard László Commissioner Trócsányi JUSTICE HEALTH INNOVATION INTERNAL AND YOUTH MARKET Phil NEIGHBORHOOD DG Justice DG Health Hogan AND and Consumers and Food Safety DG Research DG Internal ENLARGEMENT and Innovation Market, Industry, TRADE Entrepreneurship DG Neighborhood DG Trade DG Education, and SMEs and Enlargement Commissioner Youth, Sport and Negotiations Culture DG Janusz Communications Wojciechowski Networks, Commissioner Commissioner Content and AGRICULTURE Commissioner Technology Nicolas Janez Schmit Lenarčič DG Agriculture -

The New European Commission 2019-2024

The New European Commission 2019-2024 September 16, 2019 EU Public Policy On September 10, Ursula von der Leyen, President-elect of the European Commission, presented her new team. If approved by the European Parliament, they will take over from the Juncker Commission on November 1, 2019. This Alert outlines the proposed structure of the new Commission, each Commissioner’s portfolio, and the key regulatory priorities that the President set for each member of her team. A Three-Tier Commission The new President of the Commission was confronted with the same problem as her predecessor: each Member State sends a Commissioner to Brussels, but there are not 27 substantive portfolios to dole out. (The UK does not intend to send a Commissioner to Brussels, reflecting Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s stated aim of leaving the EU on October 31, before the new Commission takes office, “come what may”.) President Juncker addressed the issue by establishing a “cluster” system, with seven Vice Presidents and 20 “simple” Commissioners. In practice, however, Juncker’s Vice Presidents were not given control of specific Commission Directorates General (“DGs”), meaning that they were often relegated to “coordinating” the work of other Commissioners, without the support of officials needed to develop their own policy priorities. President von der Leyen has only slightly modified this structure, and focused on restructuring the various Commissioners’ competences to fit her “political guidelines”—the new Commission’s policymaking priorities. The new College will effectively have three “tiers” of Commissioner: 1. Three “Executive Vice Presidents”, and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy, who is ex officio a Vice President of (the “HR/VP”).