The Experience of Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena

www.ssoar.info The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Onoma, A. K. (2018). The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness. Africa Spectrum, 53(3), 65-88. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-ND Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-ND Licence Keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NoDerivatives). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/deed.de Africa Spectrum Onoma, Ato Kwamena (2018), The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness, in: Africa Spectrum, 53, 3, 65–88. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs, in co-operation with the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Freiburg, and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. -

Retention of Qualified Healthcare Workers in Rural Senegal: Lessons Learned from a Qualitative Study

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Retention of qualified healthcare workers in rural Senegal: lessons learned from a qualitative study M Nagai 1, N Fujita 1, IS Diouf 2, M Salla 2 1Division of Global Health Programs, Bureau of International Health Cooperation, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan 2Department of Human Resources, Ministry of Health and Social Actions, Dakar, Senegal Submitted: 20 July 2016; Revised: 18 April 2017, Accepted: 19 April 2017; Published: 12 September 2017 Nagai M, Fujita N, Diouf IS, Salla M Retention of qualified healthcare workers in rural Senegal: lessons learned from a qualitative study Rural and Remote Health 17: 4149. (Online) 2017 Available: http://www.rrh.org.au A B S T R A C T Introduction: Deployment and retention of a sufficient number of skilled and motivated human resources for health (HRH) at the right place and at the right time are critical to ensure people’s right to access a universal quality of health care. Vision Tokyo 2010 Network, an international network of HRH managers at the ministry of health (MoH) level in nine Francophone African countries, identified maldistribution of a limited number of healthcare personnel and their retention in rural areas as overarching problems in the member countries. The network conducted this study in Senegal to identify the determining factors for the retention of qualified HRH in rural areas, and to explore an effective and feasible policy that the MoH could implement in the member countries. Methods: Doctors, nurses, midwives and superior technicians in anesthesiology who were currently working (1) in a rural area and had been for more than 2 years, (2) in Dakar with experience of working in a rural area or (3) in Dakar without any prior experience working in a rural area were interviewed about their willingness and reasons for accepting work or continuing to work in a rural area and their suggested policies for deployment and retention of healthcare workers in rural areas. -

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal Geography and Demographics 196,722 square Size: kilometers (km2) Population: 14 million (2015) Capital: Dakar Urban: 44% (2015) Administrative 14 regions Divisions: Religion: 95% Muslim 4% Christian 1% Traditional Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2015). Note: Population and percentages are rounded. Literacy Projected 2013 Primary School 2015 Age Population (aged 2.2 million Literacy a a 7–12 years): Rates: Overall Male Female Adult (aged 2013 Primary School 56% 68% 44% 84%, up from 65% in 1999 >15 years) GER:a Youth (aged 2013 Pre-primary School 70% 76% 64% 15%,up from 3% in 1999 15–24 years) GER:a Language: French Mean: 18.4 correct words per minute When: 2009 Oral Reading Fluency: Standard deviation: 20.6 Sample EGRA Where: 11 regions 18% zero scores Resultsb 11% reading with ≥60% Reading comprehension Who: 687 P3 students Comprehension: 52% zero scores Note: EGRA = Early Grade Reading Assessment; GER = Gross Enrollment Rate; P3 = Primary Grade 3. Percentages are rounded. a Source: UNESCO (2015). b Source: Pouezevara et al. (2010). Language Number of Living Languages:a 210 Major Languagesb Estimated Populationc Government Recognized Statusd 202 DERP in Africa—Reading Materials Survey Final Report 47,000 (L1) (2015) French “Official” language 3.9 million (L2) (2013) “National” language Wolof 5.2 million (L1) (2015) de facto largest LWC Pulaar 3.5 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Serer-Sine 1.4 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Maninkakan (i.e., Malinké) 1.3 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Soninke 281,000 (L1) (2015) “National” language Jola-Fonyi (i.e., Diola) 340,000 (L1) “National” language Balant, Bayot, Guñuun, Hassanya, Jalunga, Kanjaad, Laalaa, Mandinka, Manjaaku, “National” languages Mankaañ, Mënik, Ndut, Noon, __ Oniyan, Paloor, and Saafi- Saafi Note: L1 = first language; L2 = second language; LWC = language of wider communication. -

The Ambiguity of Religious Teachings Allows People to Craft Narratives That Justify Inherited Local Burial Patterns That They Hold Dear

The ambiguity of religious teachings allows people to craft narratives that justify inherited local burial patterns that they hold dear. Should Christians and Muslims Cohabit after Death? Diverging Views in a Senegalese Commune Ato Kwamena Onoma In Senegal, some people are open to burial in cemeteries used for the departed of all faiths, while others wish to be buried only in cemeteries used exclusively for people of their own religion. Research in Fadiouth, which has a mixed cemetery, and Joal, which has segregated cemeteries, indicates that most people, regardless of their faith, embrace the dominant burial practice in their community. I argue that the ambiguity of religious doctrines through which people look at interment explains the legitimacy of local burial arrangements. Because people consume these teachings through interpretive exer- cises, even exposure to the same doctrines may not always help us understand the choices they make. This article sheds light on interfaith relations and the explanatory potential of religious teachings. Introduction In 2014, Abdou Diouf, the former president of Senegal, came under attack by some people in his hometown of Louga. He was accused of being a bad citizen of his place of origin. Specific offenses included not visiting Louga for ten years, not acquiring land there, and not developing the area during his presidency (Leral.net 2014). Beyond these preoccupations was an other- worldly transgression, which had driven some in Louga over the edge. Abdou Diouf had publicly expressed a wish to be buried in the faraway southern Senegalese city of Ziguinchor instead of Louga. Ziguinchor is one of the few Senegalese cities with a mixed cemetery, where people of all faiths can be buried. -

Demographics of Senegal: Ethnicity and Religion (By Region and Department in %)

Appendix 1 Demographics of Senegal: Ethnicity and Religion (By Region and Department in %) ETHNICITY Wolof Pulaar Jola Serer Mandinka Other NATIONAL 42.7 23.7 5.3 14.9 4.2 13.4 Diourbel: 66.7 6.9 0.2 24.8 0.2 1.2 Mbacke 84.9 8.4 0.1 8.4 0.1 1.1 Bambey 57.3 2.9 0.1 38.9 0.1 0.7 Diourbel 53.4 9.4 0.4 34.4 0.5 1.9 Saint-Louis: 30.1 61.3 0.3 0.7 0.0 7.6 Matam 3.9 88.0 0.0 1.0 0.0 8.0 Podor 5.5 89.8 0.3 0.3 0.0 4.1 Dagana 63.6 25.3 0.7 1.3 0.0 10.4 Ziguinchor: 10.4 15.1 35.5 4.5 13.7 20.8 Ziguinchor 8.2 13.5 34.5 3.4 14.4 26.0 Bignona 1.8 5.2 80.6 1.2 6.1 5.1 Oussouye 4.8 4.7 82.4 3.5 1.5 3.1 Dakar 53.8 18.5 4.7 11.6 2.8 8.6 Fatick 29.9 9.2 0.0 55.1 2.1 3.7 Kaolack 62.4 19.3 0.0 11.8 0.5 6.0 Kolda 3.4 49.5 5.9 0.0 23.6 17.6 Louga 70.1 25.3 0.0 1.2 0.0 3.4 Tamba 8.8 46.4 0.0 3.0 17.4 24.4 Thies 54.0 10.9 0.7 30.2 0.9 3.3 Continued 232 Appendix 1 Appendix 1 (continued) RELIGION Tijan Murid Khadir Other Christian Traditional Muslim NATIONAL 47.4 30.1 10.9 5.4 4.3 1.9 Diourbel: 9.5 85.3 0.0 4.1 0.0 0.3 Mbacke 4.3 91.6 3.7 0.0 0.0 0.2 Bambey 9.8 85.6 2.9 0.6 0.7 0.4 Diourbel 16.0 77.2 4.6 0.7 1.2 0.3 Saint-Louis: 80.2 6.4 8.4 3.7 0.4 0.9 Matam 88.6 2.3 3.0 4.7 0.3 1.0 Podor 93.8 1.9 2.4 0.8 0.0 1.0 Dagana 66.2 11.9 15.8 0.9 0.8 1.1 Ziguinchor: 22.9 4.0 32.0 16.3 17.1 7.7 Ziguinchor 31.2 5.0 17.6 16.2 24.2 5.8 Bignona 17.0 3.3 51.2 18.5 8.2 1.8 Oussouye 14.6 2.5 3.3 6.1 27.7 45.8 Dakar 51.5 23.4 6.9 10.9 6.7 0.7 Fatick 39.6 38.6 12.4 1.2 7.8 0.5 Kaolack 65.3 27.2 4.9 0.9 1.0 0.6 Kolda 52.7 3.6 26.0 11.1 5.0 1.6 Louga 37.3 45.9 15.1 1.2 0.1 0.5 Source: -

Dakar, Senegal

DAKAR, SENEGAL Arrive: 0800 Saturday, October 31 Onboard: 1800 Tuesday, November 3 Brief Overview: French-speaking Dakar, Senegal is the western-most city in all of Africa. The capital and largest city in Senegal, Dakar is located on the Cape Verde peninsula on the Atlantic. Dakar has maintained remnants of its French colonial past, and has much to offer both geographically and culturally. Travel north to the city of Saint Louis and see the Djoudj National Bird sanctuary, home to more than 1.5 million exotic birds, including 30 different species that have made their way south from Europe. Take a trip south from Dakar to the Delta de Saloum and enjoy the rich vegetation and water activities, like kayaking on the Gambie River. Visit the Pink Lake to see and learn from local salt harvesters. Discover the history of the Dakar slave trade with a visit to Goree Island, one of the major slave trading posts from the mid 1500s to the mid 1800s, where millions of enslaved men, women and children made their way through the “door of no return.” Touba, a city just a few hours inland from Dakar, is home to Africa’s second-largest mosque. Don’t leave Senegal without exploring one of the many outdoor markets with local crafts and traditional jewelry made by the native Fulani Senegalese tribe. Highlights: Cultural Highlights: Art and Architecture: Day 1: DAK 401-101 Casamance & Mandigo Country Day 2: DAK 105-201 Art Workshop Day 1: DAK 101-101 Goree Island Day 3: DAK 108-301 Art Tour with Lunch Day 1: DAK 103-103 Welcome Reception Nature & the Outdoors: Day 2: 201-201 La Petite Cote & Senegalese Naming Day 2: DAK 302-201 Toubacouta & Saloum Delta Ceremony Day 2: DAK 303-201 Nikolo Park & Eastern Senegal Day 2: DAK 107-301 Holy City of Touba & Thies Market Day 2: DAK 102-201 Bandia Reserve & Saly TERMS AND CONDITIONS: In selling tickets or making arrangements for field programs (including transportation, shore-side accommodations and meals), the Institute acts only as an agent for other entities who provide such services as independent contractors. -

The Wolof of Saloum: Social Structure and Rural Development in Senegal Stellingen

The Wolof of Saloum: social structure and rural development in Senegal Stellingen 1. Ein van de voorwaarden voor succesvolle toepassing van ossetrekkracht in de landbouw is een passende bedrijfsgrootte. In vele samenlevingen in West-Afrika wordt aan deze voor- waarde niet voldaan, omdat de leden van de huishoudgroep niet gezamenlijk, maar afzonder- lijk een bedrijf beheren. Dit proefschrift. 2. De conclusie dat in niet-westerse gebieden de positie van de vrouw verslechtert door opname in de marktecanomie en modernisering van de landbouw, is niet van toepassing op de Wolof-samenleving. Door de verbouw van handelsgewassen werd haar rol in de landbouw be- langrijker en nam haar inkomen toe. De recente toepassing van dierlijke trekkracht ver- lichtte haar taak op haar eigen veld. Postel-Coster, E. & J. Schrijvers, 1976. Vrouwen op weg; ontwikkeling naar emanci- patie. Van Gorcum, Assen. Dit proefschrift. 3. Moore verklaart de deelname aan werkgroepen met een maaltijd als beloning ('festive labour') mede uit de afhankelijkheid van de deelnemers ten opzichte van de begunstigde. Hierbij wordt over het hoofd gezien dat het voorkomt dat slechts een persoon deelneemt vanwege zijn afhankelijkheid van de begunstigde en dat deze persoon de overige deelnemers rekruteert volgens de regels van reciprociteit. Moore, M.P., 1975. Co-operative labour in peasant agriculture. Journal of Peasant Studies 2(3): 270-291. Dit proefschrift. 4. De gebruikelijke definitie van een marabout als zijnde een heilige en religieus leider met erg veel invloed is niet van toepassing op de Wolof, omdat hier vele marabouts slechts lokale bekendheid genieten. Dit proefschrift. 5. Er wordt vaak geen rekening gehouden met het feit dat de materiele positie van de kleine boer in ontwikkelingslanden niet alleen bepaald wordt door zijn activiteit als pro- ducent, maar tevens door zijn activiteit als handelaar. -

A Descriptive Grammar of Noon, a Cangin Language of Senegal

A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF NOON, A CANGIN LANGUAGE OF SENEGAL by Maria Soukka Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London January 1999 Department of the Languages and Cultures of Africa School of Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10672968 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672968 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Noon is a West-Atlantic language of the Cangin subgroup, spoken by 25 000 people in central Senegal, in and around the town of Thies. The aim of this study is to provide a full grammatical description of Noon, since no such study has been done on the language. We have not followed a specific linguistic model as framework, but rather tried to work from the classical approach of presenting the structures in the grammatical units of the language, from morphology to discourse. All analysis is presented with language examples from data collected in the Thies area over the years 1994-1998. The study is divided into 11 chapters, followed by a short interlinearised text sample with a free translation. -

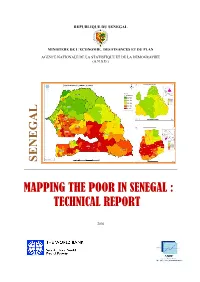

Senegal Mapping the Poor in Senegal : Technical Report

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE (A.N.S.D.) SENEGAL MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL : TECHNICAL REPORT 2016 MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL: TECHNICAL REPORT DRAFT VERSION 1. Introduction Senegal has been successful on many fronts such as social stability and democratic development; its record of economic growth and poverty reduction however has been one of mixed results. The recently completed poverty assessment in Senegal (World Bank, 2015b) shows that national poverty rates fell by 6.9 percentage points between 2001/02 and 2005/06, but subsequent progress diminished to a mere 1.6 percentage point decline between 2005/06 and 2011, from 55.2 percent in 2001 to 48.3 percent in 2005/06 to 46.7 percent in 2011. In addition, large regional disparities across the regions within Senegal exist with poverty rates decreasing from North to South (with the notable exception of Dakar). The spatial pattern of poverty in Senegal can be explained by factors such as the lack of market access and connectivity in the more isolated regions to the East and South. Inequality remains at a moderately low level on a national basis but about two-thirds of overall inequality in Senegal is due to within-region inequality and between-region inequality as a share of total inequality has been on the rise during the 2000s. As a Sahelian country, Senegal faces a critical constraint, inadequate and unreliable rainfall, which limits the opportunities in the rural economy where the majority of the population still lives to differing extents across the regions. -

Changing Cities: Climate, Youth, and Land Markets in Urban Areas

CHANGING CITIES: Climate, Youth, and Land Markets in Urban Areas A NEW GENERATION OF IDEAS Edited by Lauren E. Herzer Comparative Urban Studies Project WWW.WILSOncENTER.ORG/cuSP Available from : Comparative Urban Studies Project Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/cusp Cover Photo: “Urban View: Traffic in Hanoi,” Hanoi, Viet Nam. UN Photo/Kibae Park. www.unmultimedia.org/photo ISBN: 978-1-938027-02-4 The WOODROW WILSON INteRNATIONAL CENteR FOR SchOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by provid- ing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individu- als concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international af- fairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individu- als or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

GUIDE of SÉDHIOU Some Tips to Better Know This City of Senegal

GUIDE OF SÉDHIOU Some tips to better know this city of Senegal INDEX INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGES ..................................................................................12 ENVIRONMENT ..............................................................................16 HEALTH..........................................................................................21 EDUCATION ...................................................................................34 GREETINGS ....................................................................................41 ON THE STREETS OF SEDHIOU ........................................................48 SENEGALESE TIME .........................................................................53 THE SENEGALESE FAMILY ...............................................................56 RELIGION AND TRADITIONAL BELIEFS ............................................60 THE POLYGAMY .............................................................................68 FOOD AND DRINKS ........................................................................71 MUSIC AND DANCING ....................................................................74 ART AND GAMES ...........................................................................78 CLOTHES AND HAIRSTYLES .............................................................82 JOBS ..............................................................................................87 -

Wolof and Wolofisation: Statehood, Colonial Rule, and Identification in Senegal

chapter 3 Wolof and Wolofisation: Statehood, Colonial Rule, and Identification in Senegal Unwelcome Identifications: Colonial Conquest, Independence, and the Uneasiness with Ethnic Sentiment in Contemporary Senegal The ethnic friction which characterises classic interpretations of African states is remarkably absent in Senegalese society. Senegal is often presented as a soci- ety dominated by Wolof-speakers, particularly in the urban agglomeration of Dakar, which has assimilated large groups of immigrants both socially and lin- guistically.1 This has increasingly led scholars to define Senegal as a predomi- nantly ‘Wolof society’, whose language is spreading widely (which is sometimes seen as being linked to Murid Islam as well). The Wolof language has migrated from the region of the capital and other urban communities, such as Saint- Louis, Tivaouane, Thiès, Diourbel, and Kaolack, into the southern coastal belt towards the Gambian border. This has strongly influenced the interpretation of the history of what is present-day Senegal. Pre-colonial states are therefore often described as ‘Wolof states’; their ruling dynasties – if there were any – are defined as ‘Wolof’. The Wolof nature of Senegal’s political structures is not seri- ously in question.2 As Senegambia is located on the early modern sea routes to India and the slave ports of the so-called Guinea Coast, information on its inhabitants was available to Europeans from an early period. Such information was also pro- vided by Eurafricans, who were most strongly present in Casamance and the Cacheu-Bissau area.3 Moreover, European officials managed commercial fac- tories on Senegalese land for centuries, starting as early as the sixteenth cen- tury, although their interest was often focused more on the acquisition of slaves and less on the concrete political realities in the hinterland.