Tough Love: Bottom-Line Quality Standards for Colleges HIGHER EDUCATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nulldfr 2016 Report

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 7,500 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. IPEDS collects institution-level data on student enrollment, graduation rates, student charges, program completions, faculty, staff, and finances. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (http://collegenavigator.ed.gov), an online tool to aid in the college search process. For more information about IPEDS, see http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? As suggested by the IPEDS Technical Review Panel, the figures in this report provide selected indicators for your institution and a comparison group of institutions. The figures are based on data collected during the 2015-16 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. This report provides a list of pre-selected comparison group institutions and the criteria used for their selection. Additional information about these indicators and the pre- selected comparison group are provided in the Methodological Notes at the end of the report. -

Transfers to In-State-Private and Out-Of-State Institutions by Institution

Transfers to In-State Private and Out-of-State Institutions 2012-13 through 2016-17 2012- 2013- 2014- 2015- 2016- 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Marin CCD Total 119 120 124 118 107 In-State-Private (ISP) Total 53 56 50 50 44 Out-of-State (OOS) Total 66 64 74 68 63 2012- 2013- 2014- 2015- 2016- In-State-Private (ISP) Institutions 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Academy Of Art University 4 7 4 3 4 Academy Of Chinese Culture And Health Sc 1 Alliant International University-San Die 1 1 American College Of Traditional Chinese Med 1 Argosy University-The Art Institute Of C 3 Ashford University 1 2 1 2 Azusa Pacific University 1 Brandman University 1 Brooks Institute 1 California Baptist University 1 California College Of The Arts 3 1 1 California College San Diego 1 California Institute Of Integral Studies 1 1 2 1 California Lutheran University 1 Chapman University 2 2 1 Cogswell College 1 Concordia University-Irvine 1 Devry University-California 2 2 Dominican University Of California 17 15 12 9 10 Golden Gate University-San Francisco 3 4 2 1 ITT Technical Institute-Rancho Cordova 1 1 1 John F. Kennedy University 2 1 2 Loyola Marymount University 2 Marymount California University 1 1 Mills College 5 3 1 National University 1 1 Notre Dame De Namur University 2 2 Occidental College 1 Pacific Oaks College 1 1 Pacific Union College 1 1 Pepperdine University 1 Pitzer College 1 Planning, Research & Institutional Effectiveness Updated February 2019 1 2012- 2013- 2014- 2015- 2016- In-State-Private (ISP) Institutions 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Saint Marys College -

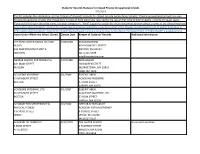

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2/2019 This list includes the information on the statuses of students' records for closed, private occupational schools. Private occupational schools are non- Private occupational schools that closed prior to August 2012 were only required by the law at that time to hold students' records for seven years; If you don't find your school by name, use your computer's "Find" feature to search the entire document by your school's name as the school may have Information about students' records for closed degree-granting institutions may be located at the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education is Information about students' records for closed hospital-based nursing programs may be located at the Department of Public Health is available here. Name Under Which the School Closed Closure Date Keeper of Students' Records Additional Information 7TH ROW CENTER HANDS-ON! CAR 7/28/2008 KEVAN BUDROW AUDIO 60 BLOOMFIELD STREET 325 NEW BOSTON ST UNIT 6 BOSTON, MA 02124 WOBURN (617) 265-6939 [email protected] ABARAE SCHOOL FOR MODELING 4/20/1990 DIDA HAGAN 442 MAIN STREET 18 WARREN STREET MALDEN GEORGETOWN, MA 01833 (508) 352-7200 ACADEMIE MODERNE 4/1/1989 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. 4/1/1987 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY & 6/9/1989 ARTHUR SCHMALBACH PHYSICAL FITNESS ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY 9 SCHOOL STREET 9 SCHOOL STREET LENOX LENOX, MA 01240 (413) 637-0317 ACADEMY OF LEARNING 9/30/2003 THE SALTER SCHOOL No records available. -

ITT Technical Institute Students and Other Interested Parties

Florida State Approving Agency for Veterans’ Education and Training 9500 Bay Pines Blvd., Room 214, Bay Pines, FL 33744 Phone: (727) 319-7406 Updated September 8, 2016 Important Information for ITT Technical Institute Students and Other Interested Parties The Florida Department of Veterans’ Affairs received notice that all ITT Technical Institute schools, nationwide, closed on September 6, 2016. Approximately 500 Florida veteran beneficiaries and thousands of non-veteran students were enrolled in programs at the 12 Florida ITT Technical Institute schools which were also approved to administer VA Education Benefits. The following information is intended to provide resources and identify services and assistance available to Florida students affected by the ITT Tech closures. Please know that you are not alone during these trying times. As you will see on the following pages, the school itself, ITT Technical Institute, is providing guidance and is offering information as to where you may acquire your transcripts as well as other pertinent information. The U.S. Department of Education has reached out to public community college and public postsecondary school leaders requesting them to provide assistance to former ITT Technical students. Other resources included in this document include information from the web pages of the Florida Department of Education, the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools and Veterans’ Affairs. Hopefully, the information provided below will help you find the resources that you need to proceed with your education plan. Topics addressed are transcript acquisition, federal student loan forgiveness, transfer of credit, prospective schools to transfer into and information pertinent to veteran beneficiaries. If you require assistance where a resource/contact is not provided to you below, please contact the Florida State Approving Agency for Veterans’ Education and Training and we will do our best to locate the individuals who can best address your issues. -

Clark College Area High School Graduates Class of 2006 One Year Follow-Up

Clark College Area High School Graduates Class of 2006 One Year Follow-up Clark College Area High School Graduates Class of 2006 One Year Follow-up Executive Summary Each year, the Office of Planning and Effectiveness compiles a report based on a one year follow-up of high school graduates in the Clark College area. Information for graduates in the Class of 2006 is reported in two groups; Area 1, which makes up about 95% of all the high school students in the Clark College area, includes Battle Ground, Camas, Evergreen, La Center, Ridgefield, Vancouver, Washougal, and Woodland School Districts, and Area 2 which includes Glenwood, Klickitat, Lyle, Stevenson-Carson, Trout Lake, White Salmon and Wishram School Districts. Highlights of Class of 2006 ♦ A total of 4,717 students graduated from high school in the Clark College area in 2006. 4,503 graduates are from Area 1 214 graduates are from Area 2 ♦ Vancouver, Evergreen, and Battle Ground School District graduates make up 76% of the Clark College area graduates. ♦ 57% (2,693) of all Clark College area high school graduates attended college within one year after graduation. ♦ 48% of all graduates attending college within one year after graduation (1,282 of 2,693) enrolled at Clark College. ♦ 27% of all area high school graduates (1,282 of 4,717) attended Clark College within one year after graduation. ♦ Clark College was the number one destination for high school graduates from the area. ♦ 78% of graduates attended in-state schools and the remaining 22% attended school outside of Washington state. Clark College Area High School Graduates Class of 2006 One Year Follow-up A College Enrollment Study is conducted each year for the Washington State Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) by the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center at Washington State University, in cooperation with the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) and Washington’s public baccalaureate colleges and universities. -

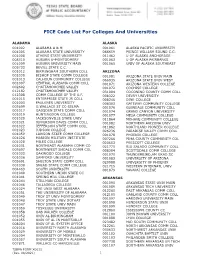

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Heald College Art Institute of California, Sacramento Hartnell College Asher University Hastings College of the Law (University of California) Azusa Pacific University Holy Names University Brigham Young University, Idaho ITT Technical Institute California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo John F. Kennedy University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Lake Tahoe Community College California State University Lincoln Law School Bakersfield Lincoln University California Maritime Academy Los Angeles Valley College Chico Los Rios Community College District Dominguez Hills American River College East Bay Cosumnes River College Fresno Folsom Lake College Fullerton Sacramento City College Humboldt McGeorge School of Law (University of the Pacific) Long Beach Mills College of California Los Angeles Moorpark College Monterey Bay Mt. San Antonio College Northridge MTI College Sacramento National University San Diego Oregon State University San Francisco Pacific Union College San Jose Pasadena City College San Marcos Rio Hondo Community College Sonoma Saint Mary’s College of California Stanislaus Samuel Merritt University Chaffey College Santa Clara University School of Law Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Sierra Community College City College of San Francisco Skyline College Contra Costa College Solano Community College Cuesta College Stanford University DeVry University Strayer University Diablo Valley College University of Arizona El Camino College University of California Fresno City College Berkeley Fresno Pacific University Davis George Mason University Irvine Glendale Community College Los Angeles Golden Gate University, San Francisco Merced Golden Gate University School of Law Riverside Note: This list is updated frequently. If you would like to hire a student from a college that’s not on the list, please call us at (916) 278-4994. -

Helpful Postsecondary Web Links

Postsecondary Education Links Last Updated: 7/16/13 Career Education Consumer Report http://www.mycareereducation.org/ The Career Education Consumer Report functions as Michigan’s workforce eligible training provider list. Michigan's Career Education Consumer Report is an electronic service in America that can help you find career education programs that are available in your area and help you choose one that fits your needs. Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) http://www.chea.org/default.asp CHEA is an association of 3,000 degree-granting colleges and universities and recognizes 60 institutional and programmatic accrediting organizations. This website is an authoritative source of data and information about regional, faith-based, private career and programmatic accreditors. It also contains databases and directories of accredited institutions and programs and accreditation or quality assurance bodies. Federal Student Aid: Closed School Information http://studentaid.ed.gov/PORTALSWebApp/students/english/closedschool.jsp?tab=attending Information on how to receive a student loan debt discharged if your school closed while you were enrolled. Federal Student Aid: The Office of Ombudsman http://www.ombudsman.ed.gov/ The Federal Student Aid Ombudsman of the Department of Education helps resolve disputes and solve other problems with federal student loans. Federal Trade Commission Facts for Consumers: Choosing a Career or Vocational School http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/consumer/products/pro13.pdf Provides tips on how to choose a career or vocational school that is reputable and trustworthy. How To Check Any Online School's Accreditation Status in One Minute or Less http://distancelearn.about.com/od/accreditationinfo/ht/checkaccredit.htm Here's how to find out if a school is accredited by an agency recognized by the United States Department of Education Job Seeker Tools http://careeronestop.org/jobseekertools/ Contains a list of top-rated job tool Web sites that include information on job openings, careers, and career advancement. -

Alabama Alaska Arizona California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Delaware Florida

Alabama Connecticut Alabama State University Post University Quinnipiac University Auburn University Sacred Heart University Community College of the Air Force Trinity College Huntingdon College University of Bridgeport Talladega College University of Connecticut Tuskegee University University of Hartford University of Alabama University of New Haven Alaska District of Columbia University of Alaska Fairbanks American University The Catholic University of America Arizona George Washington University Howard University Arizona State University Grand Canyon University Delaware Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Universal Technical Institute Delaware College of Art & Design University of Arizona Delaware State University Delaware Technical & Community College California Goldey-Beacom College University of Delaware California State University Wesley College Dominican University of California Wilmington University Santa Barbara City College San Jose State University Florida Santa Monica College University of California Barry University Eckerd College University of San Francisco Eastern Florida State College Whittier College Edison State College Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Colorado Flagler College Florida A&M University Colorado College Florida Atlantic University Colorado School of Mines Florida Gulf Coast University University of Colorado at Boulder Florida Institute of Technology United States Air Force Academy Florida International University Western Colorado University Florida Southern College Florida SouthWestern State College -

Contents • Abbreviations • International Education Codes • Us Education Codes • Canadian Education Codes July 1, 2021

CONTENTS • ABBREVIATIONS • INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES • US EDUCATION CODES • CANADIAN EDUCATION CODES JULY 1, 2021 ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN PROVINCES PROVINCES PROVINCES AL ALABAMA OH OHIO AK ALASKA OK OKLAHOMA CANADA AS AMERICAN SAMOA OR OREGON AB ALBERTA AZ ARIZONA PA PENNSYLVANIA BC BRITISH COLUMBIA AR ARKANSAS PR PUERTO RICO MB MANITOBA CA CALIFORNIA RI RHODE ISLAND NB NEW BRUNSWICK CO COLORADO SC SOUTH CAROLINA NF NEWFOUNDLAND CT CONNECTICUT SD SOUTH DAKOTA NT NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DE DELAWARE TN TENNESSEE NS NOVA SCOTIA DC DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TX TEXAS NU NUNAVUT FL FLORIDA UT UTAH ON ONTARIO GA GEORGIA VT VERMONT PE PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND GU GUAM VI US Virgin Islands QC QUEBEC HI HAWAII VA VIRGINIA SK SASKATCHEWAN ID IDAHO WA WASHINGTON YT YUKON TERRITORY IL ILLINOIS WV WEST VIRGINIA IN INDIANA WI WISCONSIN IA IOWA WY WYOMING KS KANSAS KY KENTUCKY LA LOUISIANA ME MAINE MD MARYLAND MA MASSACHUSETTS MI MICHIGAN MN MINNESOTA MS MISSISSIPPI MO MISSOURI MT MONTANA NE NEBRASKA NV NEVADA NH NEW HAMPSHIRE NJ NEW JERSEY NM NEW MEXICO NY NEW YORK NC NORTH CAROLINA ND NORTH DAKOTA MP NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS JULY 1, 2021 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES International Education RN/PN International Education RN/PN AFGHANISTAN AF99F00000 CHILE CL99F00000 ALAND ISLANDS AX99F00000 CHINA CN99F00000 ALBANIA AL99F00000 CHRISTMAS ISLAND CX99F00000 ALGERIA DZ99F00000 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CC99F00000 ANDORRA AD99F00000 COLOMBIA -

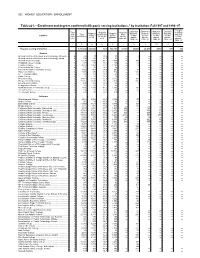

Table 221.—Enrollment and Degrees Conferred in Hispanic Serving Institutions, 1 by Institution: Fall 1997 and 1996–97

252 HIGHER EDUCATION: ENROLLMENT Table 221.—Enrollment and degrees conferred in Hispanic serving institutions, 1 by institution: Fall 1997 and 1996–97 Associate Bachelor’s Master’s Doctor’s First-pro- Type Hispanic Hispanic Hispanic Hispanic degrees, degrees, degrees, degrees, fessional Institution and Total enroll- proportion under- post- to His- to His- to His- to His- degrees, con- enrollment ment of enroll- graduate bacca- panics, panics, panics, panics, to His- trol 2 ment laureate panics, 1996–97 1996–97 1996–97 1996–97 1996–97 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hispanic serving institutions .................................... — 1,291,642 633,966 50.3 596,797 37,169 23,001 28,017 4,953 181 936 Arizona Arizona Institute of Business and Technology, Phoenix 4 243 87 35.8 87 — 8 — — — — Arizona Institute of Business and Technology, Mesa ..... 4 165 52 31.5 52 — 2 — — — — Arizona Western College ................................................. 2 6,194 2,980 48.2 2,980 — 145 — — — — Chaparral Career College ................................................ 5 373 135 36.2 135 — 23 — — — — Cochise College ............................................................... 2 4,327 1,162 27.2 1,162 — 79 — — — — Denver Business College ................................................ 4 120 34 28.3 34 — 1 — — — — Estrella Mountain Community College ............................ 2 3,010 902 30.0 902 — 36 — — — — High-Tech Institute ........................................................... 6 1,018 326 32.0 326 — 175 — — — — ITT Technical Institute ..................................................... 6 230 62 28.8 62 — 25 — — — — Parks College ................................................................... 6 78 28 35.9 28 — 1 — — — — Phoenix College ............................................................... 2 10,829 2,775 25.9 2,775 — 109 — — — — Pima Community College ................................................ 2 27,761 7,626 28.1 7,626 — 241 — — — — Pima Medical Institute ..................................................... -

Postsecondary Registration: Limiting Diploma Mills Fiscal TOPICS

Postsecondary Registration: Limiting Diploma Mills Fiscal TOPICS Published November 2008 Postsecondary Registration: Limiting Diploma Mills Chapter 261B, Code of Iowa seven representatives from two- and specialized accrediting associations. The (Registration of Postsecondary Schools) four-year public and private colleges U.S. Department of Education (USDE) does is intended to “provide protection for and universities and specialized not accredit colleges as is done by its persons choosing institutions and vocational schools and advises the ministry counterparts in many foreign programs by ensuring that accurate and Secretary of State in the countries. Instead, the USDE recognizes complete information about institutions administration of Chapter 261B. private, non-profit organizations to fulfill and programs is available to these • The Iowa Coordinating Council for this function. The Council for Higher persons and to the public.” The Post-High School Education is a 25- Education Accreditation (CHEA) is a postsecondary registration process member board made up of higher private, nonprofit national organization that regulates which institutions may offer education stakeholders. The Council coordinates accreditation and recognizes college courses and degrees within the provides voluntary cooperation and accrediting agencies in conjunction with the State. This is how Iowa limits the coordination among the various USDE. operation of diploma mills within the boards and institutions that are There are approximately 80 accrediting State. responsible for post-high school organizations in the United States that are “Diploma mills (or degree mills) are education in Iowa and advises the recognized by CHEA and/or the USDE. substandard or fraudulent ‘colleges’ College Student Aid Commission. These organizations accredit more than that offer degrees to students with little Institutions Not Required to Register 6,800 institutions and 18,000 programs.