Trinity in Unity in Christian-Muslim Relations History of Christian-Muslim Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAG. 3 / Attualita Ta Grave Questione Del Successore Di Papa Giovanni Roma

FUnitd / giovedi 6 giugno 1963 PAG. 3 / attualita ta grave questione del successore di Papa Giovanni Roma il nuovo ILDEBRANDO ANTONIUTTI — d Spellman. E' considerate un • ron- zione statunltense dl Budapest dopo ITALIA Cardinale di curia. E' ritenuto un, calliano ». - --_., ^ <. la sua partecipazione alia rivolta del • moderate*, anche se intlmo di Ot 1956 contro il regime popolare. Non CLEMENTE MICARA — Cardinale taviani. E' nato a Nimis (Udine) ALBERT MEYER — Arcivescovo si sa se verra at Conclave. Sono not) di curia, Gran Cancelliere dell'Uni- nel 1898.' Per molti anni nunzio a d) Chicago. E' nato a Milxankee nel 1903. Membro di varie congregaziont. i recenti sondaggl della Santa Sede verslta lateranense. E* nato a Fra- Madrid; sostenuto dai cardinal! spa- per risotvere il suo caso. ficati nel 1879. Noto come • conserva- gnoli. JAMES MC. INTYRE — Arclve- tore >; ha perso molta dell'influenza EFREM FORNI — Cardinale di scovo di Los Angeles. E' nato a New che aveva sotto Pic XII. E' grave. York net 1886. Membro della con mente malato. , curia. E' nato a Milano net 1889. E' OLANDA stato nominate nel 1962. gregazione conclstoriale. GIUSEPPE PIZZARDO — Cardina JOSEPH RITTER — Arcivescovo BERNARD ALFRINK — Arcivesco le di curia, Prefetto delta Congrega- '« ALBERTO DI JORIO — Cardinale vo di Utrecht. Nato a Nljkeik nel di curia. E' nato a Roma nel 1884. di Saint Louis. E' nato a New Al zione dei seminar). E' nato a Savona bany nel 1892. 1900. Figura di punta degli innovator! nel 1877. SI e sempre situate all'estre. Fu segretario nel Conclave del 1958. sia nella rivendicazione dell'autono- ma destra anche nella Curia romana. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE MEMBERS OF THE SECRETARIAT FOR NON-CHRISTIANS Friday, 27 April 1979 Dearly beloved in Christ, IT GIVES ME great pleasure to meet you, the Cardinals and Bishops from various countries who are Members of the Secretariat for Non-Christians, and the Consultors who are experts in the major world religions, as you gather here in Rome for your first Plenary Assembly. I know that you planned to hold this meeting last autumn, but that you were prevented by the dramatic events of those months. The late Paul VI, who founded this Secretariat, and so much of whose love, interest and inspiration was lavished on non-Christians, in thus no longer visibly among us, and I am that some of you wondered whether the new Pope would devote similar care and attention to the world of the non-Christian religions. In my Encyclical Redemptor Hominis I endeavoured to answer any such question. In it I made reference to Paul VI’s first Encyclical, Ecclesiam Suam, and to the Second Vatican Council, and then I wrote: “The Ecumenical Council gave a fundamental impulse to forming the Church’s self-awareness by so adequately and competently presenting to us a view of the terrestrial globe as a map of various religions... The Council document on non-Christian religions, in particular, is filled with deep esteem for the great spiritual values, indeed for the primacy of the spiritual, which in the life of mankind finds expression in religion and then in morality, with direct effects on the whole of culture”[1]. -

Denver Catholic Register Thursday, Nov

. cn o i m --J o z ^ c I m o 33 T1 X) ■y' O' *»• m o oj X) < OJ r" vtl o ^ IT J>J o t o X3 On the W ay to Sainthood Vatican City — The words and example of newspaper. “ How one humble man in four Popes Plus X II and John X X III would strengthen shcrt years could have broken down what the Church’s spiritual renovation, Pope Paul VI seemed formidable barriers . in a said at the Ecumenical Council last week, telling During World War II, the Nazi regime’s treat plete ■ ► the more than 2,300 Fathers, and distinguished ment of the Jews roused much indignation, and ■ 9 visitors, that he had initiated the beatification Pope Pius X II was attacked, decades later, in a plete cause of his predecessors. play The Deputy, by German author Rolf Hoch- riage huth, produced here and in Europe last year. con- ' h PO PE PIUS XII, whose reign lasted 19 The play blamed the late Pontiff for not strongly take years, died on Oct. 9, 1958. His successor, Pope denouncing the murder of the Jews by the Nazis. John X X III, died on June 1963. life- t. Pope Paul served as Vatican sub-secretary AMONG DEFENDERS of Pope Pius XH was Cardinal Julius Doepfner of Munich and % of state, and later as pro-secretary of state for edu- ordinary affairs, and in 1954 Pope Pius made Freising, who said that anyone who judges his irim- V him Archbishop of Milan. tory objectively, must conclude that Pope Pius XII was right when, after consulting his con . -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

At the University of Dayton, 1960-67

SOULS IN THE BALANCE: THE “HERESY AFFAIR” AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, 1960-67 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology by Mary Jude Brown UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © Copyright by Mary J. Brown All rights reserved 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVED BY: OC vj-cvcxv.c — Sandra Yocum Mize, Ph.D Dissertation Director Rev. James L. Heft, Ph.D. Ij Dissertation Reader William Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader Anthony B. Smith, Ph.BT Dissertation Reader William Trollinger, ^n.D. Dissertation Reader ■ -* w Sandra Yocum Mize, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT SOULS IN THE BALANCE: THE “HERESY AFFAIR” AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, 1960-67 Brown, Mary Jude University of Dayton, 2003 Director: Dr. Sandra Yocum Mize This dissertation examines the “Heresy Affair” at the University of Dayton, a series of events predominantly in the philosophy department that occurred when tensions between the Thomists and proponents of new philosophies reached crisis stage in fall 1966. The “Affair” culminated in a letter written by an assistant professor at Dayton to the Cincinnati archbishop, Karl J. Alter. In the letter, the professor cited a number of instances where “erroneous teachings” were “endorsed” or “openly advocated” by four faculty members. Concerned about the pastoral impact on the University of Dayton community, the professor asked the archbishop to conduct an investigation. -

Dei Agricultura Dei Aedificatio », N

CONFERENZA DEI AGRICULTURA EPISCOPALE ITALIANA DEI AEDIFICATIO CIRCOLARE INTERNA DEL SEGRET ARIATO PERMANENTE Novembre 1964 Numero 19 DALLA SANTA SEDE 1. Segreteria di Stato di Sua Santità 3 2. Sacra Congregazione Concistoriale 5 3. Sacra Congregazione Concistoriale 8 4. Sacra Congregazione del Concilio 10 5. Nunziatura Apostolica d'Italia 11 6. Nunziatura Apostolica d'Italia 15 7. Nunziatura Apostolica d'Italia 18 ATTIVITÀ DELLA C.E.1. I - SEGRETERIA 1. Lettera di Sua Ecc.za Mons. Luigi Boccadoro, Vescovo di Montefiascone e Acquapendente, Presidente del Comitato Permanente dei Congressi Eucaristici sul Congresso Eucaristico Internazionale di Bombay . .. 20 2. Relazione sull'Oasi Eucaristica di Montopoli Sabino tenuta durante l'As- semblea Plenaria dell'Episcopato Italiano, il giorno 29 ottobre 1964 22 II - I LAVORI DELLE COMMISSIONI 1. Commissione Episcopale per la S. Liturgia 28 2. Commissione per gli Strumenti delle Comunicazioni Sociali 41 3. Commissione per l'Emigrazione .... 44 4. Commissione per le Attività Catechistiche 65 5. Comitato Episcopale Italiano per l'America Latina 69 6. Ufficio Nazionale per l'Assistenza Spirituale Ospedaliera 72 Dalla Santa Sede 1 Lettera di Sua Eminenza Rev.ma il Signor Cardinale Amle.to Giovanni Cicognani) Segretario di Stato di Sua Santità) all'Ecc. ma Segretario della C.E.I.) in data 12 agosto 1964. SEGRETERIA DI STATO DI SUA SANTITÀ N.27354 Dal Vaticano, 12 agosto 1964 Eccellenza Reverendissima, Mi pregio comunicare all'Eccellenza Vostra Reverendissima che il Santo Padre Si è degnato nominare Pro-Presidente della Conferenza Epi scopale Italiana l'Em.mo Card. Luigi Traglia. Ella vorrà provvedere a· rendere opportunamente nota la sovrana disposizione. -

E Golden Rose Set Aside Lenten Pastoral National

est Catholic Paper U Notlting is more desirahle than that Catholic papers llnit~ ~tates should ha<ve a large circu Estahlished lation, so tnat e<veryone THE ,CATHOLIC TELEGRAPH may na<ve good reading." tober 22, 1831 , -PotJt Btnedict XV In Essentials, en til·.... Unit,; Non-Essentials, Libert,; in All Things, Charity. i============================~(1) VOL. LXXXXII No. ~ 10 CINCINNATI, THURSDAY, MARCH 8, 1923 PRICE SEVEN CENTS ~~~~~~~~7 ·~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ cr~ MINISTER UNACCOMPANIED, BLIND CATHOLIC CHARITIES E GOLDEN ROSE til PAPAL DELEGATE PRIEST WILL VISIT EUROPE W. BOURKE COCKRAN AMSTERDAM Declar\ ~~ .Catholic Bible May Win Allotted Big Increase From the Detroit Community Fund. ni- ~ Protestants. Rev Theophllus Beusen, of Coving .\> Renowned Orator and Statesman Dies Proposed as Scene 01 Eucharistic Con be Conferred Upon Queen 01 Receives Warm Welcome at New ton, Ky, \\ ho has been stone-bhnd for [N C, W C. News ServIce) [N C W C News ServIce] 1\\ enty ) ears, wlll make a tour of ain by Pope. Archbishop London, Feb 21.-The possibihty of York, Distinguished Churchmen Northern Europe dunng the coming Suddenly Alter Celebrating Iris DetlOlt, Mar. 1,-Catholic chanties .gress 01 1924. This Year's Meet Protestants beIng blOught back to the Summer He will VlSlt BelglUm, Hoi and institutions affiliated in the Detroit Community Union and supported by ing 'Will be Held at Paris. Filippi in Audience. Bible by means of the revised version Greet Him at the Dock. land, Germany and France, and 'mil Sixty-Ninth Birthday. uet bemg prepated at the Vahcan, IS a make the entire Joutney unaccompanied the DetrOIt Community Fund have been al10tted $370,25426 m the budget for entnnent entertamed by Rey Chad b) any personal gtl1de Tlus will be hi s Stricken With Apoplexy. -

COMPARATIVE CULTURE the Journal of Miyazaki International College Volume 14 2008

ISSN 1343-8476 COMPARATIVE CULTURE The Journal of Miyazaki International College Volume 14 2008 Jeffrey Mok 1 Before Putting Your Course Online... Brendan Rodda 5 Connections to Existing Knowledge: The Effectiveness of Methods of Vocabulary Acquisition Scott Rode 13 Of Mac and Mud: Disciplining the Unruly Victorian Street in Charles Dickens's Bleak House Debra J. Occhi 39 Translation of Jugaku Akiko (1983): “Nihonjin no kiiwaado 'rashisa'” from Kokugogaku 133:45- 54 Futoshi Kobayashi 51 Looking at Lee's Love Theory Through Abraham Maslow's Eyes: Factor Analyzing Four Different Models Anne McLellan 61 New Directions in Academic Discourse: A Howard Literature Review Míchéal Thompson 71 Choosing Among the Long Spoons: The MEP, the Catholic Church and Manchuria: 1900-1940 Creative Writing Stephen J. Davies 93 The Adventures of Magenta M: “Read, Read, Read.” ISSN 1343-8476 比 較 文 化 宮崎国際大学 第 14 巻 2008 論文 ジェフリー ・ モク 1 オンライン学習教材を取り入れる前に ブレンダン ・ロダ 5 既知の知識と結び付ける:効果的な語彙 力強化法 スコット・ロディ 13 マックとマッド: 狼藉たるビクトリア時代の 街路管理-デッケンズ「荒涼館」の記述 から デボラ・J・オチ 39 翻訳:寿岳章子「日本人のキーワード 《ら しさ》」(国語学 第 133 巻:45 頁-54 頁) 小林 太 51 Lee の愛情理論を Maslow の愛情概念 によって再解釈する試み: 四つのモデル の因子分析 アンヌ ・マクレラン・ハワード 61 資料分析:大学教育における談話の向か うべき方向 マイケル・トンプソン 71 いずれが大の虫、小の虫: MEP:カトリッ ク教会と満州 1900-1940 独創的文筆 スティーブン・J・デイビス 93 読め、ひたすら読め:マジェンタ M の冒険 Comparative Culture 14: 1-3, 2008 Before putting your course online… Jeffrey Mok 今日教育に関わる者はオンライン学習に高い関心を持っているが、オンラインを効果的に 利用できなかった教え手もいたようである。オンライン教育には使用前に考えておくべきこ とがいくつかある。本稿はオンライン教育の成否に関わるコースデザインの三要件、すなわ ち臨機応変に対応すること、現実感をもたせること、最新の情報を取り入れることの三点 について考察する。 Online learning has been and still is the buzz in educational circles today. However, some teachers may have had unsavoury experiences using it for teaching. -

Don Franco Garofalo Salvatore___

www.vesuvioweb.com Testo e ricerca di Don Franco Rivieccio 1 GAROFALO SALVATORE Testo e ricerca di Don Franco Rivieccio Torre del Greco 17 aprile 1911 - Roma 25 ottobre 1998 Salvatore Garofalo nacque a Torre del Greco in Corso Avezzana, 40 1 il giorno di Pasqua del 1911 esattamente il 17 2, era il 6 di nove figli, ma solo tre hanno raggiunta la tarda età, fu battezzato il 23 aprile dello stesso anno nella allora unica parrocchia di Torre del Greco quella di S.Croce 3, dal rev.do d. Mariano Luisi, gli furono imposti i nomi di Salvatore, Ciro, Raimondo, Maria, e fu madrina e quindi levatrice Clotilde Fagnani 4. Il suo papa Vincenzo era calzolaio e aveva un negozio di scarpe in Via Diego Colamarino 5, la madre Angela Di Donato accudiva alle faccende di casa e aiutava il marito nel cucire le scarpe a macchina, e si vive con il proprio lavoro. Salvatore frequentò le scuole elementari alla Strada Falanga 6 e qui conobbe d.Francesco Gargiulo 7, il quale lo invitò a frequentare il ricreatorio Venerabile Vincenzo Romano 8 e qui Salvatore fu uno dei primi membri del 1 reparto scautistico <<Vesuvio>> di cui era assistente il rev.do d. Stefano Perna 9, e anche membro attivo dell’Associazione 1 Attualmente è Via Roma, il palazzo è conosciuto <<da Barbato>>. L’atto di nascita civile è il n. 462 del 1911 nel quale si legge: << Il 19 aprile 1911 alle ore 12, 15 innanzi a me Luigi D’Istria Sindaco e Ufficiale di Stato Civile, si è presentato Vincenzo Garofalo di anni 34 calzolaio il quale ha dichiarato che alle ore 3,00 A. -

Marists at Vatican II Alois Greiler SM

Marists after Vatican II /Maristes après Vatican II Marists at Vatican II Alois Greiler SM In 1959 Pope John XXIII announced a Council. 50 years later we recall the Marists present at this epoch-making event. Literature on Vatican II usually highlights the protagonists. To look at the contribution of the small group of Marists (SM) opens a different perspective and forms an important memory for the Society of Mary.1 1 Marists at Vatican II (1962-1965) Full participation at Vatican II was limited to bishops and Superior Generals. Joseph Buckley, Bishops Darmancier, Julliard, Lemay, Mangers, Martin, Pearce, Rodgers, and Stuyvenberg came to all sessions. Bresson and Poncet were absent during the first, and Foley during the third, session.2 Jean-Marie Aubin (1882-1967; France; Solomons) excused himself because of illness. Two other bishops died shortly before the Council began: Joseph-Félix Blanc (1872-8.6.1962; France; Tonga) and Joseph Darnand (1879-1.6.1962; France; Samoa).3 Jakob Mangers (1889-1972) was bishop of Olso from 1953 to 1964. Norway counted less than 1% Catholics.4 The Scandinavian bishops joined the influential group of German-speaking bishops.5 The other Marist bishops worked in Oceania. Édouard Bresson (France; 1884- 1 This is an excerpt from a broader dossier put together in German in 2005. 2 Cf. Acta Synodalia, TPV (= AS), Indices, ‘Interfuerunt’. 3 Aubin, Solomons, was sick; Cf Societas Mariae, Provincia Oceaniae, In memoriam, Suva, Fiji, 2001, 188, and Acta SM 7 (1963-1967), 36. 559-561. Blanc came to Tonga in 1901 and became bishop in 1912 (In memoriam, 131). -

W0ftlu M0ur1f$

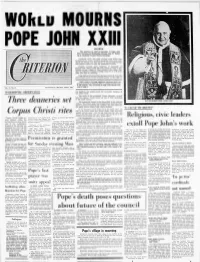

't W0ftLuM0UR1f$ PoPEJ0llt xxru BULLETIN The conclave lo elect a successor io Pope John XXlll will open on Wednesday evening, June 19. Ballot- ing is scheduled to begin lhe next morping. VA'I'ICAN CIl'Y-'Ihc body of Pope .Iohn XXIII rvas carried into St. Petcr"s basilica along thc same roulc ovcr which thc Portiff hart been ttot'ne on his nortablc thloue niue rnonths earlier to opeu the ecttmenicai council. Despite ovelcerst skies, hundrcds of thousancls of Romans and visitors lillcd the vast scluare in front of thc basilica to pay tribute to tlteir belovcrl Pope John, rvho dietl on Pentecost l,lonelay evening (Junc 3) at 7:49 p.m. after four days of suffering. L,ong before the proce,ssion cmcrgerl (June 4) florn the grcat bronze dool's of thc apcstolic palacc at thc right oI r|||ilil1iltilllltiliit|illiit||||itilt||||||||||illll||illllli|||||Illl|||llIit||||||i|||||r||Iilllit|||||llIllIllIr||[i1ii Editor's Nole-A four.plge supplemenlconlaining stories and piclureson the life of PopeJohn XXlll is includedwilh this issue of The Crilerion, Also see lrlicler on Prge 2 rnd editorialcom" ment on Prge 4. the basilictr, thc pcople ltoarrl tlte sorrorvful IIT]CIIA[tISl'IC ORSIIR VAI\C U the Julian Choir. 'fhe rvorcls of the pcuitcntial Psalm, I\'Iiserele, carlicd "llave into thc scplare: tnclcy on rne, O fiocl, accorcling to thy gLcat mercy." HIS HOLINESS POPE JOHN XXIII The proeession fotrrretl in tlrc Royal llall of the \raticarr T.'hreedeuneries set 'fhc Palaca, Popc's borly rvrs brought dorvn ll'om thc lloor "scdiari." above on a bict' carlicd bv tlte thc men rvho llore thc prqial tlrlorre cluling Fope John's lifctirne. -

REGISTER Increasingly Secularistic and Curriculum, but Emphasis Is Giv Teen-Agers” to Attest to This Mr

Churches Flourish Only for U. S. Pupils: God--the Enigma! With Education Arm tyre declared: “Perhaps only in Cardinal McIntyre asked his Los Angeles — “Is it not Washington — To combat strengthening the ‘household strangenge that in the public Russia today is the recognition audience to consider his view of God, or a Supreme Being, de points and to take “whatever the growth of secularism it is of faith.’ Whenever there has DENVERCATHaiC school system which has been faith in the ministry of nied. Are we not keeping strange action may be within the now time for Churches to ex developed in the United States, education, so that it has re company?” bounds of your competency pand their educational pro the children may not be taught ceived strong support, the and responsibility.” grams far beyond their pres that there is a God? To them "Christ is not even recognized Church, has grown; whenever amongst noteworthy men of his The Cardinal pointed to ent offerings, writes Robert He is an enigma, not the Crea faith in education has lagged, tory,” he asserted. “Each year newspaper reports of “lawless K. Bowers in Christianity To tor.” the Church has remained new subjects are added to the and irresponsible conduct of day. This charge was leveled at an static and declined. REGISTER increasingly secularistic and curriculum, but emphasis is giv teen-agers” to attest to this Mr. Bowers, a professor of atheistic trend in American ed en only to separation of religion gradual erosion of religious Christian education at Fuller “The .Apostles and the early ucation by Cardinal James from education.