The Italian Outstanding Dilemma Between Fossil Stocks and Renewable Resources: Two Apulian Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Apulia, Italy) Threatened by Xylella Fastidiosa Subsp. Pauca: a Working Possibility of Restoration

sustainability Perspective The Multi-Millennial Olive Agroecosystem of Salento (Apulia, Italy) Threatened by Xylella Fastidiosa Subsp. Pauca: A Working Possibility of Restoration Marco Scortichini CREA-Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Research Centre for Olive, Fruit and Citrus Crops, Via di Fioranello 52, I-00134 Roma, Italy; [email protected] Received: 3 July 2020; Accepted: 12 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: In Salento, the olive agro-ecosystem has lasted more than 4000 years, and represents an invaluable local heritage for landscape, trade, and social traditions. The quarantine bacterium Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca was introduced in the area from abroad and has been widely threatening olive groves in the area. The successful eradication of quarantine phytopathogens requires a prompt identification of the causative agent at the new site, a restricted infected area, a highly effective local organization for crop uprooting and biological features of the micro-organism that would guarantee its complete elimination. However, at the time of the first record, these criteria were not met. Interdisciplinary studies showed that a zinc-copper-citric acid biocomplex allowed a consistent reduction of field symptoms and pathogen cell concentration within infected olive trees. In this perspective article, it is briefly described the implementation of control strategies in some olive farms of Salento. The protocol includes spray treatment with the biocomplex during spring and summer, regular pruning of the trees and mowing of soil between February and April to reduce the juvenile of the insect vector(s). Thus far, more than 500 ha have begun to follow this eco-friendly strategy within the “infected” and “containment” areas of Salento. -

Apulia a Journey Across All Seasons

Apulia A Journey across All Seasons Pocket Guide Mario Adda Editore Regione Puglia AreA Politiche Per lA Promozione del territorio, dei sAPeri e dei tAlenti Servizio Turismo – Corso Sonnino, 177 – cap 70121 Bari Tel. +39 080.5404765 – Fax +39 080.5404721 e-mail: [email protected] www.viaggiareinpuglia.it Text: Stefania Mola Translation: Christina Jenkner Photographs: Nicola Amato and Sergio Leonardi Drawings: Saverio Romito Layout: Vincenzo Valerio ISBN 9788880829362 © Copyright 2011 Mario Adda Editore via Tanzi, 59 - Bari Tel. e fax +39 080 5539502 www.addaeditore.it [email protected] Contents A Journey across All Seasons ....................................................pag. 7 A History ............................................................................................ 9 Buried Treasures ....................................................................................... 11 Taranto’s Treasure ........................................................................ 12 Egnazia ....................................................................................... 12 The Bronzes of Brindisi ............................................................... 13 The Vases of Ruvo ....................................................................... 13 Between Legend and Reality on the Hill of Cannae ....................... 14 Ostuni – Pre-Classical Civilizations ............................................... 14 Caves and Prayers ....................................................................... -

Apulia Agro-Biodiversity Between Rediscovery and Conservation: the Case of the «Salento Km0» Network

Central European Journal of Geography and Sustainable Development 2021, Volume 3, Issue 1, Pages: 49-59 ISSN 2668-4322, ISSN-L 2668-4322 https://doi.org/10.47246/CEJGSD.2021.3.1.4 Apulia agro-biodiversity between rediscovery and conservation: the case of the «Salento km0» network Sara Nocco,* Department of History Society and Human Studies, University of Salento, Complesso Studium 2000, Ed. 5 - Via di Valesio, 73100 Lecce, Italy [email protected] Received: 31 March 2021; Revised: 20 May 2021; Accepted: 11 June 2021; Published online: 29 June 2021 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Green Revolution and the birth of the current global economic system had two opposite, subsequent effects. If, initially, they led to processes of crop homogenization, seasonal adjustment, homogenization of the landscape and markets standardization, they have subsequently pushed local communities towards a recovery of endemic biodiversity at risk of extinction because of such planetary processes, as well as a fundamental element in terms of local development, food security and sovereignty and reduction of environmental impacts. Starting from these instances of recovery and protection, which are increasingly taking place in Apulia, this work will examine both projects created "from above" and initiatives "from below", being the latter the result of a new consciousness that renews social cohesion and gives new value to the territorial milieu. In this regard, the case of the «Salento km0» network will be examined: born in 2011 and now made up of 61 local subjects including producers, restaurateurs, associations, ethical purchasing groups and traditional stores, which represent a key symbol of a territory that resists and a population that has chosen to stay and innovate according to economic, social, cultural and environmental sustainability. -

Masseria Borgo Dei Trulli LIALA Negroamaro Igp Salento IT

LIALA Negroamaro Salento INDICAZIONE GEOGRAFICA PROTETTA GRAPES: LIALA: Ladies name that 100% Negroamaro PPROTETTA means “ night” VINEYARD AREA: The grapes come from the oldest vineyards of our estate, located in the commune of Guagnano in the province of Lecce. Very low yields and carefully selected grapes are used to make this impressive Negroamaro. PLANT TRAINING AND DENSITY The training method is traditional ‘alberello pugliese’ (bush vines). The vines are approximately 80 years old, with an average yield of 700 -800g per plant. HARVEST : The grapes are harvested by hand into small 5kg crates of place from mid-September. The grapes are harvested when they are over-ripe and have begun a natural appassimento on the plant. The over-ripening allows greater concentration to be obtained, while preserving the fragrance of red fruits. VINIFICATION : After de-stemming, the grapes are not crushed, allowing them to remain intact, reducing damage to the skins and optimizing colour extraction. Fermentation takes place in stainless steel tanks at a controlled temperature of 23-25°C for 8-10 days. Selected yeasts that are ideal for Negroamaro are used for fermentation. Frequent pumping over and rack and return are carried out during the fermentation to achieve gentle extraction of aromas and supple tannins. After racking, malolactic fermentation is induced. AGING: After malolactic fermentation 70% of the wine is racked and placed in 225 litre barrels and 3,000 litre oak casks for 7-8 months. Using different sized barrels gives the wine an excellent balance of fruit and oak. The remaining 30% is placed in stainless steel tanks. -

Case Study Puglia

COESIONET RESEAU D ’ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LA COHESION ET LES TERRITOIRES EN EUROPE Case Study The Apulia Region Patrizia Luongo June 2011 Etude co-financée par l’Union Européenne dans le cadre d’Europ’Act. L’Europe s’engage en France avec le Fonds européen de développement régional 2 List of Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................................................4 2. Demographic changes and migration flows .................................................................................6 3. The socio-economic framework .................................................................................................... 10 3.1 GDP, Poverty and Social Exclusion .........................................................................................................10 3.2 Production System .......................................................................................................................................13 3.2.1 Regional disparities ................................................................................................................................................14 3.2.2 Interviews’ Results ..................................................................................................................................................15 3.3 The Labour Market.......................................................................................................................................16 3.3.1 Interviews’ -

An Assessment of Agritourism in Salento (Apulia) in the Era of the Internet

Giuseppe Calignano An assessment of agritourism in Salento (Apulia) in the era of the internet Abstract Apulia is the region with the highest overall growth rate of agritourism units in Italy in the period 2008-2012. This article aims at analysing and assessing the prospective demand, dynamics, evolution and number of these specifi c rural facilities in Salento – a sub-region of Apulia formed by the provinces of Lecce, Brindisi and Taranto – in the so-called “era of the internet”. By using quantitative and qualitative techniques it has been able to determine that Lecce is the leading province in Salento and in Apulia in terms of number and diffusion of agritourism facilities. Furthermore, the fi ndings of this study suggest that the possibilities offered by the internet and the new media are not suffi ciently used by agritourism operators in Salento and in other areas – like in Tuscany and Trentino-Alto Adige, where agritourism activities boast a long tradition – to promote their services and products they offer. Keywords : Agritourism, Salento, Internet. Introduction All of these subcategories – equally included in the concept of global tourism – have been created Throughout history tourism has been strongly with the aim of satisfying an increasingly demand- infl uenced and sometimes determined by chang- ing clientele. However, these “tourisms” can take es which have marked paths and evolution of credit for having led to rediscover values such as various societies. Several socioeconomic, cultural environmental safeguard and sustainability. and technological factors have led to the gradual The purpose of these “tourisms” is to be re- transition from the so-called “proto-tourism” – an sponsible and alternative to other forms of tour- expression including leisure and travel activities ism which are characterized by a strong human carried out from the classical antiquity till the impact: agritourism is included among these end of 1700s – to the forms of tourism, created ones. -

Vigneto Giardinelli Salice Salentino

Vigneto Giardinelli Salice Salentino Producer: Agricole Vallone Winemaker: Graziana Grassini Country of Origin: Italy Region of Origin: Puglia Grapes: Negroamaro 100% ABV: 13% Case Size: 6x75cl Vintage: 2012 Suitable For: Vegetarians and Vegans Closure Type: Cork The One-Liner Warm, generous, characterful southern Italian red from one of Puglia's great estates. Tasting Note The nose is ripe and openly fruity with hints of liquorice and raisins. The palate has a touch of spice, somewhat Syrah-like, to balance the black fruit and ripe tannins. A wonderful balance of sweet ripeness and bitterness, typical of Negro Amaro, held together by fresh acidity and given added complexity by a touch of spicy oak. Producer Details Founded in 1943, this family owned producer owns 600 hectares over three estates in the Salento peninsula. Vineyards cover 170 hectares, the rest are planted with a plethora of other agricultural crops, including some of the oldest olive groves in the country. Supported by viticulturalist Donato Lazzari, the Vallone sisters produce wines consistently rated amongst the best in Puglia. Agricole Vallone has two different winemaking facilities, each with the most advanced, up-to-date equipment. The Flaminio estate, near Brindisi, houses the cellar where all the wines are vinified, while the Copertino cellar, in the province of Lecce, carries out the process of maturation in oak, both large 'botti' and small French oak barrels. Both 2001 and 2003 vintages of Graticciaia were awarded 'Tre Bicchieri' in the Gambero Rosso 'Wines of Italy' guide, one of only 7 wines in Puglia to receive Italy's most high profile wine accolade. -

SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Children in Southern Italy: a Descriptive Case Series

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children in Southern Italy: A Descriptive Case Series Daniela Loconsole 1, Desirèe Caselli 2, Francesca Centrone 1 , Caterina Morcavallo 1, Silvia Campanella 1, Maurizio Aricò 3 and Maria Chironna 1,* 1 Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology-Hygiene Section, University of Bari, Piazza G. Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (S.C.) 2 Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Giovanni XXIII Children Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico, Piazza G. Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 3 COVID Emergency Task Force, Giovanni XXIII Children Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico, Piazza G. Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-080-547-8498; Fax: +39-080-559-3887 Received: 29 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: At the beginning of the coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Italy was one of the most affected countries in Europe. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is less frequent and less severe in children than in adults. This study analyzed the frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infection among all children aged <18 years in the Apulia region of southern Italy and the characteristics of the infected children. Clinical and demographic data were collected through the national platform for COVID-19 surveillance. Of the 166 infected children in the Apulia region, 104 (62.6%) were asymptomatic, 37 (22.3%) had mild infections, 22 (13.3%) had moderate infections, and 3 (1.8%) had severe infections. -

Lecce As Smart Student City?

EUniverCities Lecce Peer Review Report: Lecce as Smart Student City? Results Peer Review Meeting Lecce (28-30 January 2015) By Dr. Willem van Winden, Lead Expert EUniverCities [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Context: City & University ..................................................................................................... 4 3. City-university co-operation: an overview ............................................................................. 6 4. Results of the peer review .................................................................................................... 7 Annex 1 Programme of the meeting.......................................................................................... 9 2 1. Introduction Cities compete to attract and retain skilled people and knowledge-intensive business, and universities are a key “asset” in this respect. They attract students, who could become valuable human resources for companies in the city. Smaller university cities have a harder job to retain graduates than bigger ones. Their job markets are smaller and less attractive. This is particularly true for Lecce, a university city in the South of Italy where the economy is less well-developed and the job market for highly-skilled people is weak. Most students of its university (the University of Salento) leave after the conclusion of their studies, for a lack of highly qualified -

United Nations

UNITED NATIONS UNEP/MED WG.468/Inf.21 UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN 9 August 2019 Original: English Meeting of the MAP Focal Points Athens, Greece, 10-13 September 2019 Agenda Items 3 and 4: Progress Report on Activities Carried Out during the 2018–2019 Biennium and Financial Report for 2016–2017 and 2018–2019 Agenda Item 5: Specific Matters for Consideration and Action by the Meeting, including Draft Decisions Draft Feasibility Study for a Transboundary CAMP Project between Albania and Italy (Otranto Strait area) For environmental and cost-saving reasons, this document is printed in a limited number. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copies to meetings and not to request additional copies UNEP/MAP Athens, 2019 UNEP/MED WG.468/Inf.21 Page 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Definition of the area for CAMP ................................................................................................................... -

Mobility Management Plan for the City of LECCE

Mobility Management Plan for the City of LECCE 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 2. MM Plan - Template .............................................................................................. 3 Headline / Title ..................................................................................................... 3 A. Acknowledgement ........................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2: Feasibility / Existing Conditions ...................................................... 12 Chapter 3: Overall Goals ................................................................................. 18 Chapter 4: Implementations / Activities ............................................................ 18 Chapter 5: Monitoring and Evaluation .............................................................. 24 Chapter 6: Conclusion ......................................................................................... Appendixes ........................................................................................................ 26 2 1. Introduction This template is designed for the partners support in the development of the Mobility management Plan and is to be used in combination with the WP 3 training outputs and the WP 4.1 self assessment results. It provides a suggested -

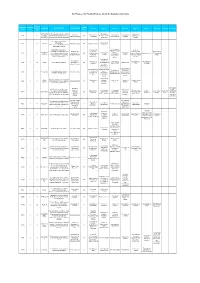

Not Proposed for Funding Project Proposals Below Thresholds

Not Proposed for Funding Projects - Below the Evaluation thresholds SPECIFIC REGISTER PRIORITY COUNTRY OBJECTI ACRONYM PROJECT TITLE LEAD PARTNER Partner 2 Partner 3 Partner 4 Partner 5 Partner 6 Partner 7 Partner 8 Partner 9 Partner 10 NUMBER AXIS (GR/IT) VE CULTOURN An IT supported network of cultural Municipal & Chamber of Economic Egnatia Epirus Developing Municipality of 8370 1 1.1 ET FOR and tourism actors and businesses GR Regional Theater Commerce of Chamber of Epirus Foundation MURGIA SPA* Putignano BUSINESS in the regions of Epirus and Apulia of Ioannina Brindisi Greek-Italian Commodities Marketplace: Prefecture of 8068 1 1.2 S.E.A.P. Prefecture of Ilia GR Province of Lecce Observatory – Stock Exchange of Preveza Agricultural Products Development BUSINESS-making in the Development Centre for Agency For South countryside - Alternatives for the Development Agency of Research and Prefecture of BUSINESS Prefecture of Epirus - Province of 8123 1 1.2 Access of Unemployed Young Enterprise of GR Aitoloakarnania Experimentation in Informa S.c.a.r.l. Kefallinia and EQUAL Lefkada Amvrakikos Brindisi People and Women to EQUAL Achaia Prefecture Prefecture Agriculture “Basile Ithaki Etanam S.A. Rights of Employment (ΑΝΑΙΤ) S.A. Caramia” L.G.O. Development Development Agency of Prefecture of University of Municipality of Municipality of 8125 1 1.2 GreEn Green Entrepreneurship Enterprise of GR Aitoloakarnania Laser Center Ioannina Patras - ELKE Bari Carovigno Achaia Prefecture Prefecture (ΑΝΑΙΤ) S.A. Development Regional Banks- AICAI-Agency of agency for South Development Enterprises Vertical Social Network of the the Chamber of Epirus- 8180 1 1.2 Energybook Province of Bari IT Enterprise of the Observatory of renewable energy cluster Commerce of Amvrakikos Achaia Prefecture Economy and Bari Etanam S.A.