In Honor of Sandra Levy Festschrift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Spiritual Experiences in Healing From

DRAWING FROM THE WELL: WOMEN’S SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCES IN HEALING FROM CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE by Jill Louise Wylie A thesis submitted to the School of Rehabilitation Therapy In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2010 Copyright ©Jill Louise Wylie, 2010 Abstract The prevalence of child sexual abuse remains high with girls 1.5 to 3 times more likely to be victims compared to boys. In addition to psychological and emotional challenges, this abuse can lead to spiritual difficulties that impact survivors’ ability to find meaning in their life, find a sense of purpose, experience hope or believe in a world that is just. Spirituality can facilitate healing and this study contributes to that knowledge base by exploring women’s own perspectives. The purpose of this qualitative narrative study is to understand, from women’s perspectives, the role of spiritual experiences in their healing from the impacts of child sexual abuse. Spiritual experiences were defined as any experiences that have a different reality or feeling compared to our usual everyday reality that may seem extraordinary or unexplainable, or very ordinary yet meaningful. Twenty in-depth individual interviews were conducted with ten women survivors of child sexual abuse. Narrative analysis methods were used to derive key themes that represent participants’ perspectives of how spiritual experiences enhance healing. Results of this study show that spiritual experiences opened doorways to self, shifted energy, expanded perspective, revealed truths, connected to the present moment, created possibilities of the positive and were an enduring source of support and strength. -

Albany Student Press 1981-05-01

11111 i-l 11111I j1111 M 111111 mi 11 II 111111iI 11iI 11II1111 I I I 11 II I I I II I I II II I I i II Trackmen Romp page 18 April 28, 1981 Danes Sweep Colgate as Esposito Gets Record by Bob Bellaflore sixth when Rhodes (2-3) doubled to to bunt him over, but Masseroni's As a rule, Division III teams are the right field corner. Designated throw pulled Rowlands off the bag not supposed to beat Division I runner Steve Shucker went to third and both men were on. Kratley Cocks' New Contract is Recommended teams. on Colgate hurlcr Joe Spofford's struck out on three pitches, but Staats singled to right and Nuti by Belli Sexer So much for rules. wild pitch, and came in on Lynch's portant llial he be shown .support. scored. positive recommendation he looks The Albany State varsity baseball line single to center. Faeully and students afire over Marlin said lhai on a personal all accounts one of Ihe besl teachers team won its eighth game in a row Colgate's runs were all unearned. Colgate went up 2-1 in the next Vice President for Academic Af for "a balance of leaching and in ihc university should be sum level he had "mixed emotions" and scholarship and university service." and increased their already im They got one in the fifth when John inning. Tortorello went deep in the fairs David Martin's recommenda "severe reservations" about his marily canned" for not publishing pressive record to 10-1 by sweeping Kratley reached on a force play, hole at shortstop to field Dave tion thai Political Science Professor Martin's firs! recommendation enough, he said. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

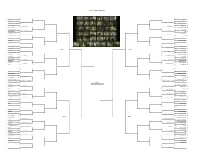

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\Desktop

The Twilight Zone Checklist SEASON ONE (1959-60) Episode Aired Stars U Where Is Everybody? 10/2/59 Earl Holliman, James Gregory One for the Angels 10/9/59 Ed Wynn, Murray Hamilton Mr. Denton on Doomsday 10/16/59 Dan Duryea, Martin Landau The 16-Millimeter Shrine 10/23/59 Ida Lupino, Martin Balsam Walking Distance 10/30/59 Gig Young, Frank Overton Escape Clause 11/06/59 David Wayne, Thomas Gomez The Lonely 11/13/59 Jack Warden, Jean Marsh Time Enough at Last 11/20/59 Burgess Meredith, Jacqueline DeWitt Perchance to Dream 11/27/59 Richard Conte, Suzanne Lloyd Judgment Night 12/04/59 Nehemiah Persoff, Ben Wright, Patrick Macnee And When The Sky Was Opened 12/11/59 Rod Taylor, Charles Aidman, Jim Hutton What You Need 12/25/59 Steve Cochran, Ernest Truex, Arlene Martel The Four of Us Are Dying 01/01/60 Harry Townes, Ross Martin Third from the Sun 01/08/60 Fritz Weaver, Joe Maross I Shot An Arrow Into the Air 01/16/60 Dewey Martin, Edward Binns The Hitch-Hiker 01/22/60 Inger Stevens, Leonard Strong The Fever 01/29/60 Everett Sloane, Vivi Janiss The Last Flight 02/05/60 Kenneth Haigh, Simon Scott The Purple Testament 02/12/60 William Reynolds, Dick York Elegy 02/19/60 Cecil Kellaway, Jeff Morrow, Kevin Hagen Mirror Image 02/26/60 Vera Miles, Martin Milner The Monsters Are Due on Maple St 03/04/60 Claude Atkins, Barry Atwater, Jack Weston A World of Difference 03/11/60 Howard Duff, Eileen Ryan, David White Long Live Walter Jameson 03/18/60 Kevin McCarthy, Estelle Winwood People Are Alike All Over 03/25/60 Roddy McDowall, Susan Oliver The Twilight Zone Checklist SEASON ONE - continued Episode Aired Stars UUU Execution 04/01/60 Albert Salmi, Russell Johnson The Big Tall Wish 04/08/60 Ivan Dixon, Steven Perry A Nice Place to Visit 04/15/60 Larry Blyden, Sebastien Cabot Nightmare as a Child 04/29/60 Janice Rule, Terry Burnham A Stop at Willoughby 05/06/60 James Daly, Howard Smith The Chaser 05/13/60 George Grizzard, John McIntire A Passage for Trumpet 05/20/60 Jack Klugman, Mary Webster Mr. -

ANGELS CAUGHT NAPPING: MOMENTS THAT DEFINE US By

ANGELS CAUGHT NAPPING: MOMENTS THAT DEFINE US by JANET MARIE DOGGETT, B.A. A THESIS IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved i^h^rperson of the Committee Accepted Dean of the Graduate School May, 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my mentor and thesis advisor Jill Patterson for her kind support and encouragement and also committee member, professor and poet- extraordinaire, John Poch, who has said more than once, "It's good. It's not a poem, but it's good," Also, without the guidance and support of Dr. Jon Rossini during my first semester, I would not have remained in graduate school. This book is dedicated to my mother for understanding that it's not about blame; for my husband who reads my work and loves me anyway, and for my kids who have eaten pizza more nights than any children should. And finally, I would like to acknowledge all of the women and children with whom I worked for a period of two years as a volunteer at the Lubbock Rape Crisis Center. Their courage in the face of horror, their strength and their hope for all things better, will always resonate in my heart, move me to tell their stories, and push me to do better. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i, CHAPTER I. PREFACE 1 II. UNFEATHERED BABY BIRDS 6 Too Much Information 7 Consulting Caroline 21 Me in the Mirror 28 III. IN A SHOEBOX, LIGHTLY 35 A Rather Figgy Afternoon 36 For Lack of a Better Title 40 Angels Caught Napping 47 IV. -

La Zona Del Crepuscolo Di Aleksandar Mickovic E Marcello Rossi

La zona del crepuscolo di Aleksandar Mickovic e Marcello Rossi Dal 1959, intere generazioni di telespettatori sono rimaste affascinate, terrorizzate o semplicemente conquistate dalle trame di una delle più memorabili serie televisive mai realizzate: Ai c i i r t (The Twilight Zone, 1959-1964). Nei suoi 156 episodi non vengono narrate le vicende di un gruppo di personaggi che puntata dopo puntata vivono avventure simili tra loro, ma una varietà di semplici storie che attendono di essere raccontate... o vissute i i i r t è infatti una serie antologica, senza personaggi e interpreti fissi, in ui g i pis i r hiu u st ri mp t L‟u i pu t i ri rim t st t è u distinto signore con una sottile cravatta nera, con il compito di introdurre gli spettatori nella zona r pus : R S r i g M S r i g r s t t ‟ spit s ri ; g i è st t i r t r , ‟ ut r pri ip i pr utt r i i i r t debuttò sugli schermi statunitensi il 2 ottobre 1959, ma la sua storia inizia ben due anni prima, quando Rod Serling, un affermato sceneggiatore televisivo, ultimò il pi p r u p ssibi pis i pi t i tit t “Th Tim E m t” Serling aveva iniziato a scrivere prima per la radio e poi per la televisione già ai tempi dei suoi stu i g , si r r pi m t gu g t u ‟ ttim r put zi N 1958, ‟ t i 33 i, v iv r t ‟Emmy w r (g i Os r p r t visi ) p r t rz v t S r i g aveva dimostrato di essere uno scrittore di talento soprattutto nel genere drammatico; aveva raggiunto sia il successo artistico che quello finanziario. -

Super! Drama TV January 2021 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 2:00-6:00 on the 14Th

Super! drama TV January 2021 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 2:00-6:00 on the 14th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.12.28 2020.12.29 2020.12.30 2020.12.31 2021.01.01 2021.01.02 2021.01.03 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 06:00 06:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 06:00 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 6 06:00 Season 3 Season 3 #7 #1「'CHAOS' Part One」 #12「'SOS' Part One」 「Boom-Boom-Boom-Boom」 06:30 06:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 06:30 06:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 06:30 Season 3 Season 3 #2「'CHAOS' Part Two」 #13「'SOS' Part Two」 07:00 07:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 07:00 07:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 07:00 THE TWILIGHT ZONE(2019) 07:00 Season 3 Season 3 #6 #3「PATH OF DESTRUCTION」 #14「'SIGNALS' Part One」 「Six Degrees of Freedom」 07:30 07:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 07:30 07:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 07:30 Season 3 Season 3 #4「NIGHT AND DAY」 #15「'SIGNALS' Part Two」 08:00 08:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 08:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 ★Ultraman: The Alien Invasion [J] 08:00 Season 3 Season 3 #5「GROWING PAINS」 #16「CHAIN REACTION」 08:30 08:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:30 08:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:30 Season 3 Season 3 #6「LIFE SIGNS」 #17「GETAWAY」 09:00 09:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 09:00 09:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 09:00 Season 3 Season 3 #7「RALLY RAID」 #18「AVALANCHE」 09:30 09:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 09:30 09:30 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 09:30 Season 3 Season 3 #8「CRASH COURSE」 #19「UPSIDE DOWN」 10:00 10:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 10:00 10:00 ★THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 10:00 ★Ultraman: The Battle for Earth 10:00 Season 3 Season 3 [J] -

African Literature Readings on Truth and Reconciliation

AFRICAN LITERATURE READINGS ON TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION Gambia Ghana Kenya Liberia Mauritius Morocco Nigeria Rwanda Sierra Leone South Africa Tunisia Uganda Dr. Melike YILMAZ Africa map: https://www.vecteezy.com Book symbol: https://clipartart.com • Gambia - Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission • Ghana – National Reconciliation Commission Report • Kenya – Truth, Justice and Reconciliation • Liberia – Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report • Mauritius – Truth and Justice Commission Report • Morocco – Equity and Reconciliation Commission (IER) • Nigeria – Human Rights Violations Investigations Commission (HRVIC) Report (Unofficial) • Rwanda – International Commission of Investigation of Human Rights Violations in Rwanda • Sierra Leone – Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report • South Africa – Truth and Reconciliation Commission • Tunisia – Truth and Dignity Commission Report • Uganda – Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances You can find more information about Truth Commission Reports on this link: https://truthcommissions.humanities.mcmaster.ca/ “I dedicate this to all those who did not live to tell it. And may they please forgive me for not having seen it all nor remembered it all, for not having divined all of it.” -Alexander Soljenitsin from The Gulag Archipelago ** INTRODUCTION This study is a literature review based on the “Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission” set up in twelve African countries; Morocco, Nigeria, Ghana, Gambia, Mauritius, South Africa, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Tunisia. Fiction and non-fiction books written on the subject by African authors were detected and the following text was prepared, which consists of brief summaries of the books, their cover pages and related comments*. This study will be of assistance to readers and researchers of both fiction as well as non-fiction. -

The Influence of Cultural Schema on L2 Production: Analysis

THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL SCHEMA ON L2 PRODUCTION: ANALYSIS OF NATIVE RUSSIAN SPEAKERS’ ENGLISH PERSONAL NARRATIVES A Thesis by MARY ELIZABETH CUNNINGHAM Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction The Influence of Cultural Schema on L2 Production: Analysis of Native Russian Speakers’ English Personal Narratives Copyright 2011 Mary Elizabeth Cunningham THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL SCHEMA ON L2 PRODUCTION: ANALYSIS OF NATIVE RUSSIAN SPEAKERS’ ENGLISH PERSONAL NARRATIVES A Thesis by MARY ELIZABETH CUNNINGHAM Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, Zohreh Eslami Committee Members, M. Carolyn Clark Radhika Viruru Head of Department, Dennie Smith August 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT The Influence of Cultural Schema on L2 Production: Analysis of Native Russian Speakers’ English Personal Narratives. (August 2011) Mary Elizabeth Cunningham, B.A., Baylor University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Zohreh Eslami The present study focuses on 24 personal narratives told by eight highly proficient bilingual L1-Russian, L2-English speakers (NRS) in comparison to 24 personal narratives told by eight native English speakers (NES) in an effort to not only discover any structural differences that may be revealed through statistical analysis, -

Twilight Zone Nightmare As a Child Cast

Twilight zone nightmare as a child cast Fantasy · A schoolteacher keeps seeing a strange little girl in her apartment building. The Twilight Zone (–) Episode complete credited cast. Watch The Twilight Zone - Season 1, Episode 29 - Nightmare as a Child: Schoolteacher Helen Foley finds a Cast & Crew: RECURRING AND GUESTS · EDIT. With the entire original run of The Twilight Zone available to watch instantly, we're partnering with Twitch Film to cover all of the show's Original airdate: April 29, Cast: Helen Foley: Janice Rule. Markie: Terry Next week on the Twilight Zone, 'Nightmare as a Child.' I hope. Watch The Twilight Zone: Nightmare as a Child from Season 1 at The Twilight Zone - Guy Gets Stuck In The Twilight Zone Guest Cast. One of the largest lists of directors and actors by MUBI. The actors on this list are ranked according to MUBI users rating. The Twilight Zone Episode Nightmare as a Child Cast: Rod Serling, Janice Rule, Shepperd Strudwick, Terry Burnham, Michael Fox, and The Twilight Zone Episode 48: DustJanuary 2. Find movie and film cast and crew information for The Twilight Zone: Nightmare as a Child () - Alvin Ganzer on AllMovie. A schoolteacher who has blocked out the details of her mother\'s murder encounters a strange little girl intent on making her recall the murderer\'s identity. Sure, “Nightmare” has a fairly typical Twilight Zone twist, but what it's really about is a woman realizing that the death of her mother wasn't what. Child on Find trailers, reviews, and all info for The Twilight Zone: Nightmare as a Child by Alvin Ganzer. -

To Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 4 x 2” ad YourYour Community Community Voice Voice for 50for Years 50 Years RecorPONTEecorPONTE VED VEDRARAdderer entertainmententertainment EEXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! April 2 - 8, 2020 has a new home at The Pritchett-Dunphy band is breaking up: THE LINKS! ‘Modern Family’ signs off 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 The award-winning ABC comedy Jacksonville Beach “Modern Family” airs its series fi nale Wednesday. Ask about our Offering: 1/2 OFF · Hydrafacials All Services · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections · Botox & Fillers · Medical Weight Loss VIRTUAL CONSULTATIONS Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: Kathleen Floryan List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while REALTOR® Broker Associate the home is listed • An edge in the local market LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with WITH ME! ListSecure® I will provide you a FREE America’s Preferred 904-687-5146 Home Warranty for [email protected] your home when we put www.kathleenfloryan.com it on the market.