ANGELS CAUGHT NAPPING: MOMENTS THAT DEFINE US By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 191 10/10/11

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 191 10 October 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 191 10 October 2011 Contents Introduction 4 Notice of Sanction Al Ehya Digital Television Limited Saturday Night Special, 13 November 2010 5 Note to Broadcasters Publication of new guidance and research 7 Standards cases In Breach Aden Live 27 October 2010, 18:20 (16:20 GMT) to 29 October 2010, 19:00 (17:00 GMT) 15 November 2010, 10:00 (08:00 GMT) to 16 November 2010, 10:00 (08:00 GMT) 8 Pro Bull Riders trailer Extreme Sports, 19 July 2011, 13:00 31 Howard Taylor at Breakfast Total Star – Wiltshire, 20 May 2011, 06:00 33 The Baby Borrowers Really, 2 August 2011, 20:00 36 Music video programming Brit Asia TV, 11 June 2011 38 Sponsorship of various programmes B4U Music, 15 June 2011, 21:00 to 22:42 42 Resolved Station promotion 106 Jack FM, 2 August 2011, 10:30 47 Fairness and Privacy cases Upheld Complaint by Mr David Gemmell Grimefighters, ITV1, 12 April 2011 49 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 191 10 October 2011 Not Upheld Complaint by Dr Saeb Erakat on his own behalf and on behalf of the Palestine Liberation Organisation The Palestine Papers, Al Jazeera English, 23 to 26 January 2011 53 Other programmes Not in Breach 72 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 73 Investigations List 79 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 191 10 October 2011 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. -

How One Company Is Selling Dreams

How One Company Is Selling Dreams China Intercontinental Press (and Dish Soap) Follow Us on Advertising Hotline WeChat Now 城市漫步珠 in China 国内统一刊号: 三角英文版 that's guangzhou that's shenzhen CN 11-5234/GO NOVEMBER 2017 11月份 that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Editor in Chief Jocelyn Richards Shenzhen Editor Sky Thomas Gidge Senior Digital Editor Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang National Arts Editor Erica Martin Contributors Gary Bailer, Ariana Crisafulli, Lena Gidwani, Dr. Adam Koh, Mia Li, Noelle Mateer, Dominic Ngai, Adam Robbins, Wilson Tong HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 : 100027 9G, Block C, Ginza Mall, No. -

Sotm Card Guide - All Heroes

SotM Card Guide - All Heroes Absolute Zero Character Shtick: ‘The Frozen Mech-Warrior.’ Absolute Zero deals damage in big bursts to himself and others using modular armor upgrades as well as frost and fire-themed powers. Ramp Up: Very slow. Absolute Zero must have and keep key equipment cards in play to be at all functional in the game. Character Card Nemeses: Iron Legacy, Proletariat HP: 29 Primary dmg: Cold, fire Complexity: 3 Name Description Effect Thermodynamics Power: 1 fire dmg or 1 cold dmg to Absolute Zero. card. Damage – Single; Survivability – Self Incapacitated One hero uses a power; +2 dmg for hero; Destroy target with 1 hp. Freedom Six Absolute Zero Name Description Effect Elemental Wrath Power: 2 cold dmg to 1 non-hero target. Damage – Single Incapacitated One hero draws 1 card; 1 cold dmg to target; no environment cards for 1 turn. Deck Stats One-Shots: 5 (15) Ongoing: 6 (12) Equipment: 4 (13) Damage – single: 4 (11) [+4 (10)] Support – self: 4 (13) Damage – multi: 3 (6) [+1 (2)] Support – group: 0 (0) Survivability – self: 2 (6) [+7(19)] Hindrance/ Deck Control: 2 (4) Survivability – group: 0 (0) Damage Single Target: Name Type # Description Frost-Bound One-Shot 3 3 cold dmg to 1 target; 3 fire dmg to Absolute Zero. Drain Coolant Blast Ongoing 2 Power: x cold dmg to 1 target, x = amount of fire dmg taken by Absolute Zero since end of last turn. Impale Ongoing 2 Play on 1 non-hero target; start of turn, 2 cold dmg to target. Isothermic Equipment, 4 X cold dmg to 1 target, x = any fire dmg taken by Absolute Transducer Limited, Module Zero. -

Scheherazade

SCHEHERAZADE The MPC Literary Magazine Issue 9 Scheherazade Issue 9 Managing Editors Windsor Buzza Gunnar Cumming Readers Jeff Barnard, Michael Beck, Emilie Bufford, Claire Chandler, Angel Chenevert, Skylen Fail, Shay Golub, Robin Jepsen, Davis Mendez Faculty Advisor Henry Marchand Special Thanks Michele Brock Diane Boynton Keith Eubanks Michelle Morneau Lisa Ziska-Marchand i Submissions Scheherazade considers submissions of poetry, short fiction, creative nonfiction, novel excerpts, creative nonfiction book excerpts, graphic art, and photography from students of Monterey Peninsula College. To submit your own original creative work, please follow the instructions for uploading at: http://www.mpc.edu/scheherazade-submission There are no limitations on style or subject matter; bilingual submissions are welcome if the writer can provide equally accomplished work in both languages. Please do not include your name or page numbers in the work. The magazine is published in the spring semester annually; submissions are accepted year-round. Scheherazade is available in print form at the MPC library, area public libraries, Bookbuyers on Lighthouse Avenue in Monterey, The Friends of the Marina Library Community Bookstore on Reservation Road in Marina, and elsewhere. The magazine is also published online at mpc.edu/scheherazade ii Contents Issue 9 Spring 2019 Cover Art: Grandfather’s Walnut Tree, by Windsor Buzza Short Fiction Thank You Cards, by Cheryl Ku ................................................................... 1 The Bureau of Ungentlemanly Warfare, by Windsor Buzza ......... 18 Springtime in Ireland, by Rawan Elyas .................................................. 35 The Divine Wind of Midnight, by Clark Coleman .............................. 40 Westley, by Alivia Peters ............................................................................. 65 The Headmaster, by Windsor Buzza ...................................................... 74 Memoir Roller Derby Dreams, by Audrey Word ................................................ -

That's Not My Baby...Thankfully

EDITION: U.S. Maria Shriver Smarter Ideas More Log in News Web Search News and Topics Like 379K CONNECT FRONT POLITICS BUSINESS ENTERTAINMEN TECH MEDIA LIFE & CULTUR COMEDYHEALTHY LIVING WORL LOCAL MORE PAGE T STYLE E D DIVORCE LIVING HEALTH NUTRITION Tamara Lynch GET UPDATES FROM TAMARA LYNCH PHOTO GALLERIES Like 1 That's Not My Baby...Thankfully Posted: 7/22/11 11:57 AM ET React Amazing Inspiring Funny Scary Hot Crazy Important Weird Top 10 Low-Down JLo And Marc: Read more Divorce News Dirtiest Divorce Scenes From A Tricks Marriage One weekday afternoon during my lunch hour a SHARE THIS STORY coworker told me about Weddingchannel.com. "You can type in your Ex's name and it will search all the registries. You can see if he got married," she Get Divorce Alerts said shoving a salad in her mouth and regaling me VOTE: Which Star JLo's Many Men: A Couple Has The Look Back Sign Up with tales of her own cyber stalking. Most Stable... It had been five years since I'd divorced my ex Submit this story husband Dave*. We met in our '20s and married in our '30. I told myself I didn't care if he got re- FOLLOW US married; it was my decision to end it...but I was curious. Not only did I find a bridal registry, but a Google search led me to his Facebook profile. I wasn't ready for what came next. Pudgy cheeks, dark fuzz, big eyes. A baby, his baby, sat propped on my ex's chest. -

Angel Island to Island Angel on Reynolds Camp Established

9/27/05, 4:29 PM 4:29 9/27/05, 1 layout2005 AIbrochurePDF Printed on Recycled Paper Recycled on Printed ) /0 . (Rev Parks State California 2003 © 7 1 (415) 435-1915 (415) Tiburon, CA 94920 CA Tiburon, P.O. Box 318 Box P.O. Angel Island State Park State Island Angel www.parks.ca.gov 711, TTY relay service relay TTY 711, (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. the outside 653-6995, (916) For information call: (800) 777-0369 (800) call: information For Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 CA Sacramento, P. O. Box 942896 Box O. P. Golden Gate Bridge. Gate Golden CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS STATE CALIFORNIA Marin County and the and County Marin Office at the following address. following the at Office views of San Francisco, San of views alternate format, write to the Communications the to write format, alternate number below. To receive this publication in an in publication this receive To below. number sites and breathtaking and sites assistance should contact the park at the phone the at park the contact should assistance arrival, visitors with disabilities who need who disabilities with visitors arrival, access to many historic many to access against individuals with disabilities. Prior to Prior disabilities. with individuals against California State Parks does not discriminate not does Parks State California the land, providing easy providing land, the and roads crisscross roads and station. Today, trails Today, station. and as an immigration an as and for high-quality outdoor recreation. outdoor high-quality for settlement of the West the of settlement cultural -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

O fcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 117 15 September 2008 Standards cases In Breach World’s Most Amazing Videos 4 TV6, 28 June 2008, 20:00 “Wake Up Your Brain” competition 7 James and Ali in the Morning, Invicta FM, 20 December 2007, 06:00 “Worst Girlfriend” competition 9 Lloydie and Katie Show, Power FM, 14 March 2007, 16:00 Full Pott 11 Kanal 5, 16 July 2008; 09:00 Breakfast 13 Kiss 105, 10 April 2008, 08:00 Peter Popoff Ministries 14 Ben TV, 29 February 2008, 16:30 Paul Lewis Ministry Ben TV, 20 March 2008, 16:00 Peter Popoff Ministries Red TV, 24 March 2008, 17:30 The Soup 17 E! Entertainment, 19 July 2008, 23:00 Stripped 18 The Style Network, 2 July 2008, 11:00 Biggles 20 Movies4Men+1, 21 June 2008; 16:20 Eid Messages 22 Aapna Channel, 24 December 2007, 17:00 Deepam TV 23 Non-retention of off-air recordings and sponsored news bulletins up to July 2008 Karl Davies Breakfast Show 25 Tudno FM, 7 August 2008, 7:45 and 8 August 2008, 8:20 Note to Broadcasters – Recordings 26 2 Resolved BBC News 27 BBC1, 2 July 2008, 22:00 Not in Breach The F Word 29 Channel 4, 29 July 2008, 21:00 Fairness & Privacy Cases Not Upheld Complaint by Ms Jenny Thoresson made on her behalf by 30 Ms Ann-Kristin Thoresson Lyxfällan (Luxury Trap), TV3 Sweden, 12 April 2007 (and repeated 23 July 2007) 3 Standards cases In Breach World’s Most Amazing Videos TV6, 28 June 2008, 20:00 Introduction TV6 is a Swedish language channel operated by Viasat Broadcasting UK Limited (“Viasat”). -

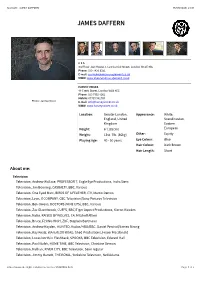

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

S H a P E S O F a P O C a Ly P

Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought M y t h s a n d ta b o o s i n R u s s i a n C u lt u R e Series Editor: Alyssa DinegA gillespie—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana Editorial Board: eliot Borenstein—New York University, New York Julia BekmAn ChadagA—Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota nancy ConDee—University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg Caryl emerson—Princeton University, Princeton Bernice glAtzer rosenthAl—Fordham University, New York marcus levitt—USC, Los Angeles Alex Martin—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana irene Masing-DeliC—Ohio State University, Columbus Joe pesChio—University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee irina reyfmAn—Columbia University, New York stephanie SanDler—Harvard University, Cambridge Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought Edited by Andrea OppO BOSTON / 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-61811-174-6 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-618111-968 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Konstantin Juon, “The New Planet,” 1921. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. -

NWS Tampa Bay 2009-2010 Winter Newsletter

Suncoast Weather Observer Winter 2009 Issue 1, Volume 14 Inside This Issue... Severe Thunderstorm Warning Hail Criteria Becomes More Meaningful 2009 Hurricane Season Summary Sea Fog: A Simple Tutorial NWS Ruskin Supports the American Cancer Society by Participating in Relay For Life NWS Ruskin Gives Back to the Community El Niño to Increase Possibility of Hazardous Weather in Florida this Winter NWS Ruskin to Host an Open House “Disponible en Español”...Spanish Services Keep on Growing SPECIAL FEATURE: January 2010 Cold Snap Severe Thunderstorm Warning Hail Criteria Becomes More Meaningful By: Daniel Noah Since January 5, 2010, Severe Thunderstorm Warnings across the nation are now issued for 1 inch or larger hail instead of the previous 3/4 inch or larger size hail. The wind criteria of 58 MPH (50 knots) did not change. Scientific research increasingly indicates that significant damage to real property does not occur until hail stones reach at least 1 inch in diameter. The results of these peer-reviewed articles are supported by damage reports from thousands of archived storm events. Many in the media and the emergency management community were concerned that too many Severe Thunderstorm Warnings were being issued for marginal events and these warnings were desensitizing the public. The new 1 inch criteria will reduce the number of Severe Thunderstorm Warnings each season and will warn for a genuine risk of damage and a corresponding need to take protective action. The 15 counties in west central and southwest Florida received 109 reports of 3/4 inch hail or larger over the past two years, and of these, only 35 hail reports were 1 inch or larger. -

Frankly in Love Rom-Com Centered on Immigrant Identity ISBN: 978-1-984-81222-3

Frankly In Love Rom-Com Centered on Immigrant Identity ISBN: 978-1-984-81222-3 Korean-American teen Frank Li and his parents don’t see eye to eye when it comes to dating. He just wants to have a girlfriend; they just want him to have a Korean girlfriend. When fellow Korean-American Joy Song agrees to a fake relationship, he gets to hide his real girlfriend and she gets to hide her real boyfriend. They think they’ve found the perfect solution, but soon enough, Frank’s complicated love life leaves him wondering if he ever really understood love—or himself—at all. before we begin Well, I have two names. That’s what I say when people ask me what my middle name is. I say: Well, I have two names. My first name is Frank Li. Mom-n-Dad gave me that name mostly with the character count in mind. No, really: F+R+A+N+K+L+I contains seven characters, and seven is a lucky number in America. Frank is my American name, meaning it’s my name-name. My second name is Sung-Min Li, and it’s my Korean name, and it follows similar numerological cosmology: S+U+N+G+M+I+N+L+I contains nine characters, and nine is a lucky number in Korea. Nobody calls me Sung- Min, not even Mom-n-Dad. They just call me Frank. So I don’t have a middle name. Instead, I have two names. Anyway: I guess having both lucky numbers seven and nine is supposed to make me some kind of bridge between cultures or some shit.