Climate Gentrification: Flooding the Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARCH MORTGAGE INSURANCE COMPANY NAIC Group Code.....1279, 1279 NAIC Company Code

PROPERTY AND CASUALTY COMPANIES - ASSOCIATION EDITION *40266201920100101* QUARTERLY STATEMENT As of March 31, 2019 of the Condition and Affairs of the ARCH MORTGAGE INSURANCE COMPANY NAIC Group Code.....1279, 1279 NAIC Company Code..... 40266 Employer's ID Number..... 36-3105660 (Current Period) (Prior Period) Organized under the Laws of WI State of Domicile or Port of Entry WI Country of Domicile US Incorporated/Organized..... December 30, 1980 Commenced Business..... December 31, 1981 Statutory Home Office 33 East Main Street, Suite 900 .. Madison .. WI .. US .. 53703 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Main Administrative Office 230 North Elm Street .. Greensboro .. NC .. US .. 27401 336-373-0232 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Mail Address Post Office Box 20597 .. Greensboro .. NC .. US .. 27420 (Street and Number or P. O. Box) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Primary Location of Books and Records 230 North Elm Street .. Greensboro .. NC .. US .. 27401 336-373-0232 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Internet Web Site Address www.archmi.com Statutory Statement Contact Jeffrey Wayne Shaw 336-412-0800 (Name) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) (Extension) [email protected] 336-217-4402 (E-Mail Address) (Fax Number) OFFICERS Name Title Name Title 1. Robert Michael Schmeiser # President & Chief Executive Officer 2. Sara Fitzgerald Millard Executive Vice President, General -

Report on Rent Control (1981)

Citizens League Report on Rent Control Prepared by Special Studies Task Force Donald Van Hulzen, Chairman Approved by Citizens League Board of Directors February 18,1981 Citizens League 530 Syndicate Building Minneapolis, MN 5 5402 (612) 338-0791 INTRODUCTION We were asked by the Citizens League Board of Directors in to deal only with rent control, and that took almost all of the fall of 1980 to develop and recommend a League our time. position on rent control. Our charge instructs us to (a) become familiar with the facts on the price of rental We don't fully understand what is happening, but there are housing and how rents have increased in comparison with some signs which indicate that the financial burden ques- other essential living expenses; (b) try to understand tion will emerge as a far more serious issue in the 1980s specific problems to which rent control proposals are being than many persons now recognize. In most income cat- addressed, and reach conclusions on the extent to which egories, housing will be claiming a larger portion of the these problems would be met through rent control; (c) household budget. Persons most significantly affected will become familiar with the extent to which rent control is in be those of low income who are using current income to existence elsewhere in the nation, and the results in these pay for housing, whether through rent or mortgage pay- locations; and (d) determine the impact which rent control ments. would have on maintenance of rental dwellings, new construction of rental dwellings, housing demand in parts Most of us are familiar with the fact that higher energy of the metropolitan area without rent control, supply and prices, higher interest rates and higher inflation rates have cost of housing for low md moderate-income households, resulted in significant increases in housing costs. -

Principles of Eminent Domain

Principles of Eminent Domain House Joint Resolution No. 34 Proposed Legislation Volume I1 Legislative Environmental Quality Council Eminent Domain Subcommittee Public Benefits and Private Rights: Countervailing Principles of Eminent Domain Proposed Legislation September 2000 Environmental Quality Council Members House Members Senate Members Representative Paul Clark Senator Mack Cole Representative Kim Gillan, Vice-Chair Senator William Crismore, Chair Representative Monica Lindeen* Senator Bea McCarthy Representative Doug Mood Senator Ken Mesaros Representative Bill lash Senator Barry "Spook" Stang Representative Cindy Younkin Senator Jon Tester Public Members Governor's Representative Mr. Tom Ebzery Ms. Julie Lapeyre Ms. Julia Page Mr. Jerry Sorensen Mr. Howard F. Strause Law, Justice, and Indian Affairs Committee Members on Eminent Domain Subcommittee Representative Gail Gutsche Representative Dan McGee Representative Jim Shockley *Eminent Domain Subcommittee merr~bersare noted in italics Legislative Environmental Policy Off ice Staff Todd Everts, Legislative Environmental Analyst; Larry Mitchell, Resource Policy Analyst; Mary Vandenbosch, Resource Policy Analyst; Krista Lee, Resource Policy Analyst; Maureen Theisen, Publications Coordinator; State Capitol, P.O. Box 20 1704, Helena, MT 59620- 1 704; (406) 444-3742; http://leg.state.mt.us Eminent Domain Study Staff Krista Lee, Resource Policy Analyst, Legislative Environmental Policy Office; Gordon Higgins, Research Analyst, Legislative Services Division; Greg Petesch, Chief Legal Counsel, Legislative Services Division 'The bill drafts in this report are in the form in which they were adopted by the Environmental Quality Council at its September 2000 meeting. For the most current versions of these bills, call the Legislative Environmental Policy Office at (406) 444- 3742 or view the online version by choosing Legislative Info from the State of Montana homepage, then 2001 Session. -

Guide to Taking Mortgages in Moldova [EBRD

2008 Guide to taking mortgages in Moldova Guide to taking mortgages in Moldova Prepared by A.C.I. Partners European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Chisinau, 2008 © ACI Partners, 2008 © European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, without the written permission of the copyright holders. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature. This publication has been made possible thanks to the generous support of the Swiss Government. The information and expression of opinions in this guide are not intended to constitute legal advice and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. As the law related to the area of security is complex, we strongly recommend seeking legal advice when contemplating specific transactions. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................4 An explanation of the terms used......................................................................................................4 Key features of new legislation..........................................................................................................5 Laws governing mortgages................................................................................................................5 -

Real Estate Syndication: Property, Promotion, and the Need for Protection

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 69 APRIL 1960 NUMBER 5 REAL ESTATE SYNDICATION: PROPERTY, PROMOTION, AND THE NEED FOR PROTECTION CURTIS J. BERGERt READERS of the June 29, 1958, edition of the Mew York Times may have puzzled over a sixteen page advertising supplement urging them to buy units in a syndicate that would soon acquire the leasehold on one of Manhattan's prominent office buildings.' For many, this was their first glimpse of syndica- tion-a technique that has become the vogue in real estate investment.2 Syn- tInstructor in Law, Yale Law School 1959-1960. The author is indebted for assistance in research on a portion of this Article to Mr. Donald P. Horwitz, a third-year student at the Yale Law School. 1. N.Y. Times, June 29, 1958, § 10. The promoters of Motors Building Realty Com- pany sought to raise $5,780,000 to acquire the leasehold of the General Motors Building. 2. Towards the end of WVorld War II, several forces ended the doldrums which had characterized real estate investment throughout the 1930's and early 1940's. Individual sav- ings accumulated during the war sought investment outlets. U.S. BunRAu oF THE CEN- sus, DEP'T OF ComimRce, STATISTICAL ABSTRACT OF THE UNrED STATES 436, 457 (1956). Lending institutions were ready to disgorge, often at bargain basement values, their de- pression-acquired foreclosed realty holdings. Mfunicipally-owned land, the product of de- pression tax foreclosures, became attractively available to developers. The governmental stimulus of insured or guaranteed mortgages, National Housing Act, 48 Stat. 1246 (1934), as amended, 12 U.S.C. -

GENTRIFICATION and CRIME New Configurations and Challenges for the City

Delft University of Technology Gentrification & Crime New Configurations and Challenges for the City Leoni, Giovanni ; Hein, C.M.; Semi, Giovanni ; La Spina, Antonio ; Mirabile, Mario ; Cabras, Edoardo ; Bonura, Massimo ; Arena, Alessio ; Mirabile, Mario ; Cattafi, Carmelo Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Citation (APA) Leoni, G. (Ed.), Hein, C. M. (Ed.), Semi, G. (Ed.), La Spina, A. (Ed.), Mirabile, M. (Ed.), Cabras, E. (Ed.), Bonura, M., Arena, A., Mirabile, M., Cattafi, C., La Spina, A., Bighelli, C., Panagiotakopoulos, D., & Cabras, E. (2020). Gentrification & Crime: New Configurations and Challenges for the City . (CPCL Series). TU Delft Open. Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Giovanni Semi Antonio La Spina Mario Mirabile Edoardo Cabras GENTRIFICATION AND CRIME New Configurations and Challenges for the City -

Real Estate Update

Spring 2008 REAL ESTATE UPDATE ATLANTIC YARDS—PUBLIC TAKING OR PRETEXT? The Atlantic Yards Arena and Redevelopment Project in Atlantic Yards—Public Brooklyn overcame a legal challenge on February 1, 2008, in Taking or Pretext? ..................1 the case of Goldstein v. Pataki, decided by the United States Second Circuit Court of Appeals. The plaintiffs-appellants, You Scratch My Back, and fifteen property owners whose homes and businesses are slated I’ll Scratch Yours....................2 for condemnation to make way for the project, sought to block its construction. They argued that the condemnation or “taking” of the private LLC Derivative Suits— property of existing home and business owners to assemble the large swath of land New York Court of Appeals Moves the Law required by the project violates the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, which Closer to Delaware..................4 reads, in part, “Private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” An expansive reading of the Fifth Amendment might lead one to conclude that as long as the owners of private property are justly compensated, their private property may be taken. This has never been the holding of the Supreme Court of the United States, however. The Supreme Court precedents all first require that the taking be for a “public purpose.” The definition of public purpose has, however, expanded more and more over the centuries. First, the entity to which the private property is given does not have to be a government or public entity; it can be another private individual who is going to put the property to a public use. -

Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol

15019 Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol. 83, No. 68 Monday, April 9, 2018 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER property collateral that is consistent are regulated by the agencies (regulated contains regulatory documents having general with safe and sound banking practices. institutions) would not be required to applicability and legal effect, most of which DATES: This final rule is effective on obtain appraisals in connection with are keyed to and codified in the Code of commercial real estate transactions Federal Regulations, which is published under April 9, 2018. 50 titles pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 1510. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: (commercial real estate appraisal OCC: G. Kevin Lawton, Appraiser threshold) from $250,000 to $400,000. The Code of Federal Regulations is sold by (Real Estate Specialist), (202) 649–7152, The proposal followed the completion the Superintendent of Documents. Mitchell E. Plave, Special Counsel, in early 2017 of the regulatory review Legislative and Regulatory Activities process required by the Economic Division, (202) 649–5490, or Joanne Growth and Regulatory Paperwork DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Phillips, Attorney, Bank Activities and Reduction Act (EGRPRA).3 During the Office of the Comptroller of the Structure Division, (202) 649–5500, EGRPRA process, the agencies received Currency Office of the Comptroller of the numerous comments related to the Title Currency, 400 7th Street SW, XI appraisal regulations, including 12 CFR Part 34 Washington, DC 20219. For persons recommendations to increase the who are deaf or hearing impaired, TTY thresholds at or below which [Docket No. OCC–2017–0011] users may contact (202) 649–5597. -

Reform of American Conveyancing Formality Robert D

Hastings Law Journal Volume 32 | Issue 3 Article 1 1-1981 Reform of American Conveyancing Formality Robert D. Brussack Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert D. Brussack, Reform of American Conveyancing Formality, 32 Hastings L.J. 561 (1981). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol32/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Reform of American Conveyancing Formality By ROBERT D. BRUSSACK* Symbolic twigs and clumps of soil no longer are essential props at real estate closings1 but modern American conveyancing does have its rituals. In most states, for example, a transferee should insist that the transferor appear before a notary public and acknowledge execution of the conveyance.2 The transferee also should make certain that the notary affixes a proper certificate of acknowledgment to the conveyance. An omitted or defective ac- knowledgment will not invalidate the conveyance between the par- ties in most states,8 but it may well produce other calamitous con- sequences. The defectively formalized conveyance often is not eligible for recording in the official land records,4 and even if the transferee makes sure the instrument is physically placed in the records where a reasonably diligent title searcher would find it, the conveyance will not be given effect as constructive notice of the transaction. 5 Thus, a subsequent purchaser who fails to search the records, or who searches them poorly, may prevail over the initial transferee6 simply because the earlier conveyance lacks a proper notary's certificate. -

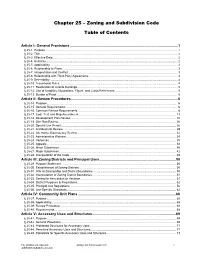

Chapter 25 – Zoning and Subdivision Code Table of Contents

Chapter 25 – Zoning and Subdivision Code Table of Contents Article I: General Provisions ..........................................................................................................1 § 25-1. Purpose................................................................................................................................................................. 1 § 25-2. Title. ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 § 25-3. Effective Date. ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 § 25-4. Authority. ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 § 25-5. Applicability. .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 § 25-6. Relationship to Plans. ........................................................................................................................................... 3 § 25-7. Interpretation and Conflict. .................................................................................................................................... 3 § 25-8. Relationship with Third-Party Agreements. .......................................................................................................... -

Appraisal Report

Appraisal Report Multifamily Capitalization Rate (OAR) Effective Gross Income Multiplier (EGIM) State of Kansas Report Date: October 29, 2020 Kansas Department of Revenue Angela Brown 900 Southwest Jackson, Suite 451-South Topeka, Kansas 66612 Valbridge Property Advisors / Kansas City 10990 Quivira Road, Suite 100 Overland Park, Kansas 66210 (913) 451-1451 phone Valbridge File Number: (913) 529-4121 fax KS01-20-0345 valbridge.com 10990 Quivira Road, Suite 100 Overland Park, Kansas 66210 (913) 451-1451 phone (913) 529-4121 fax valbridge.com October 29, 2020 Angela Brown Kansas Department of Revenue 900 Southwest Jackson, Suite 451-South Topeka, Kansas 66612 RE: Appraisal Report Multifamily Capitalization Rate Effective Gross Income Multiplier State of Kansas Dear Ms. Brown: In accordance with your request, we have performed an appraisal of the above referenced scope of work. The appraisal report sets forth the pertinent data gathered, the techniques employed, and the reasoning leading to our value opinions. This letter of transmittal is not valid if separated from the appraisal report. The report includes the development of an overall multifamily capitalization rate and an effective gross income multiplier (EGIM) analysis for affordable housing properties in the State of Kansas. The study will be used by the Kansas Department of Revenue and Kansas County Appraisers in the valuation of federally sponsored affordable housing projects within the State of Kansas. The analysis includes the following components: Capitalization rate analysis using traditional sales A capitalization rate analysis using the Band of Investments An effective gross income multiplier analysis An expense ratio analysis We developed our analyses, opinions, and conclusions and prepared this report in conformity with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) of the Appraisal Foundation and the Code of Professional Ethics and Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice of the Appraisal Institute. -

Emerging Trends in Real Estate®

2003EMERGING TRENDS IN REAL ESTATE® Emerging Trends in Real Estate Additional copies of Emerging Trends are is a registered trademark of available at $95 each from: PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Lend Lease Real Estate Investments, Inc. Copyright © October 2002, 909 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10022. Lend Lease Real Estate Investments Attention: Emerging Trends and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP or email requests to: All rights reserved. [email protected] PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP 1747 Veterans Highway, Suite 48, Islandia, NY 11722 or email requests to: [email protected] 71515 p1_3.QXD 10/4/02 6:40 PM Page 1 DIFFERENT WORLD, TEMPERED EXPECTATIONS Contents Foreword 1 Chapter 1 Different World, Tempered Expectations 2 Chapter 2 The Survey: Investment Trends 2003 14 Chapter 3 Capital Flows 22 Chapter 4 Markets to Watch 32 Chapter 5 Property Types in Perspective 44 Interview/Survey Participants 2003 58 71515 p1_3.QXD 10/4/02 6:40 PM Page 2 EDITORIAL BOARD Emerging Trends Chairs Patrick R. Leardo Fred N. Pratt, Jr. Editor/Author Jonathan D. Miller Editorial Board Lijian Chen Peter F. Korpacz M. Leanne Lachman Steven P. Laposa Jeanette Rice Robert K. Ruggles, III Susan M. Smith Paul Summer Dan Van Dyke Interviews and Surveys Conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers Editorial Review and Production Cathie Bartels, Martha Althafer, Charlotte Decker, Donna Douglass, Ryan Dunlap, Caroline Green, Bernadette T. Korpacz, Marilyn Robson, Philip Thai, Bonnie White The editors would like to thank our colleagues for their time and insights: