And Lalithambika Antharjanam's 'Agnisakshi'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Stock.Pdf

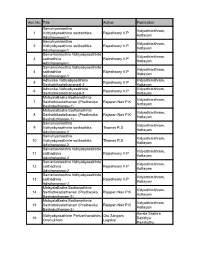

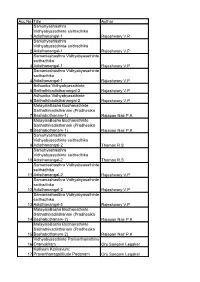

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS) REFLECTIONS ON ANTHARJANAM: AN INTERVIEW WITH TANUJA BHATTATHIRIPAD Allu Alfred Research Scholar University of Madras Chennai, Tamil Nadu Lalithambika Antharjanam was a prominent writer and a social reformer who recieved the Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award and the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award for her novel Agnisakshi in 1977. She focused on the issues of Namboothiri women and worked towards their emancipation from archaic parctices within the community through her writing. The following is an interview with writer Tanuja Bhattathiripad, Antharjanam's grand daughter and a current writer in Malayalam on the life and times of her grandmother and the sweeping changes in the position of women in Kerala today: 1. Given your personal association with Lalithambika Antharjanam and your position as a member of the present day Namboothiri community, how do you think your grandmother's work affected the female members of the community? Where her works accessible to women at the time it was written and more importantly were the women allowed to read at the time? Did the Namboothiri women find a connection with her works or were they critical for speaking against age old coustoms? TB: I believe that my grandmother’s works have influenced the female members of the Namboothiri community to a large extent. I suppose I am an example in my generation, to the degree of influence her works have had. I consider that the relevance of her works have only increased with the passage of time. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Retell 2016 April

ISSN 0973-404X Research Teaching Learning Letters (An inter-disciplinary Research Journal) Vol. 16, April 2016 St. Joseph’s College (Autonomous) Special Heritage Status Awarded by UGC,, Accredited at ‘A’ Grade (3rd Cycle) by NAAC,, College with Potential for Excellence by UGC,, DBT-STAR & DST-FIST Sponsored College Tiruchirappalli - 620 002 Tamil Nadu, India Tel: 0431-2700320 / 4226436 / 4226376,, Fax: 0431-2701501 e-Mail: [email protected] tni..edu / www..sjctni.edu © The publisher / editor is not responsible for errors in the contents, for any omission, copyright violation or any consequence arising from the use of information published in ReTELL. Authors are the sole owners of the copyright of the respective articles. Research Teaching Learning Letters (An inter-disciplinary Research Journal) Vol. 16, April 2016 ISSN 0973 -404X St. JOSEPH’S COLLEGE (Autonomous) Special Heritage Status Awarded by UGC, Accredited at ‘A’ Grade (3rd Cycle) by NAAC, College with Potential for Excellence by UGC, DBT-STAR & DST-FIST Sponsored College TIRUCHIRAPPALLI - 620 002 Tamil Nadu, India Tel: 0431-2700320 / 4226436 / 4226376, Fax: 0431-2701501 e-Mail: [email protected] / www.sjctni.edu From the Editorial Team There are two cardinal principles that a good editorial is about: an opinion making and about balancing. If it is based on evidence, so much the better; yet it analyses evidence rather than produces it. What it analyses can be the basis of the production of new evidence. Meanwhile we intend to inform the young scholars that RETELL has travelled quite a distance – from one of an in-house reading to an ISSN numbered multidisciplinary journal. -

Acc.No. Title

Acc.No. Title Author Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 1 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 2 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 3 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 4 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 5 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 6 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 7 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 8 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 9 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 10 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 11 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 12 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 13 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 14 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 15 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Vidhyabyasathinte Parivarthanathinu 16 Oramukham Oru Sangam Legakar Kalliyum Kariyavum: 17 Pravarthanagallillude Padanam Oru Sangam Legakar MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 18 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Adhunika Vidhyabyasaprakriya: 19 Vikasanavum Pravannathakallum Sivarajan -

District Census Handbook, Kollam, Part XII-A & B, Series-33

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES - 33 KERALA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK KOllAM SHEELA THOMAS OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, KERALA 37/154/2007-1 MOTJ:F The light house at Thangasserv, five kms. from Kolhm Town, is the chief attraction of tourists. A silent sentinel since the tum of the Century, the light house was built in 1902. It was reconstructed in 1940 by A. N. Seal, Engineer-in-Chief of Light House Department. The light emanating from 144 feet light house is visible at a distance of 18 miles out in the sea. The surging surface of the sea on one side and the panorama oflush green coconut trees on the other side are seen from the top. It was built to safeguard seamen from treacherous reefs of Thangassery. ,...-_ - I~- ~~~---- _-._ () , -~ l- II \,, <t_J oo_ ~ <t C ) Co::: -- ... , I / Z UI :E .(' ::: q o. ~ « _,_L _. -, 0 ,/ ~ l i e) I- / U f" cr: f l CC o e/) ~- o (f) ~ « 0 cr: ::> n... L_ « r I I -r Z -'- « I- Z ~ « « > ::> z cr: « I il I I- I- <;>- C. I iI I I 1 o r - U Ii cc i l- (f) I- 0 « , I>- ~ I :2 X:.- N CO I ::> I i r.;: ~ 0.. zX 0. X:.- ~ I ~ <C . ~ _ 1 < ;< \) 0z < \" L1J '(\ UJ'" S >- E +- ro I>- ~ >- 15 ~ '" iii \.- ~ u I 0 ;;; ~ ~ ~ iij I ~ ID ~ ~ D ~ "' '" ;;;" ~ ~ ro ro ;:; ~ ~ en 0 ~ (.) :;; 0: 0 '"0 z en Cl 0:: CONTENTS Page Foreword Vll Preface ix Acknowledgements x District Highlights - 2001 Census Xl Important Statistics in the District Xll Ranking ofTaluks in the District xiv Statements (1-9) Statement -1 : Name of the Headquarters of DistrictfTaluk, their rural-urban status -

Amrita Kiranam March 2016

No. 10 | Vol. 12 | MARCH 2016 a snapshot and journal of happenings @ Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi Green Festival at Amrita by SEED 2 Janam TV Campus Fest IT 2020 - Computer Society of India (CSI) Regional Meet 3 National Level Workshop on Android Application Development 4 ‘PRABHATHI’ - General quiz program for differently abled Workshop on Finance and Online Trading 5 CSI Activities 6 National Conference on Innovations in Marketing Spandanam 2016 7 ASTHRA 2016 Camera Speaks 9 Nottam Film Festival 10 Workshop on Advertising / Cinematography National Seminar on Cinema and the Formation of Cultural 13 Identities Bharatanatyam Performance 15 Workshop on Numerical Methods Using MATLAB / OCTAVE INSIDE..... 16 ENLYTUS-A PR Campaign Green Festival at Amrita by SEED A grand harvest festival was held at the campus on 6th February, 2016. The State coordinator of ‘SEED’, an initiative of Mathrubhumi, Sri. Vinod, Spoke about the success of Mathrubhumi ‘SEED’ programme and congratulated the school on its success with organic farming. Swami Purnamritananda Puri lit the sacred lamp and inaugurated the programme. Sri. Sachidanandan, a Military Engineer and parent of a SEED volunteer, spoke about his passion for organic farming. It was an inspiring speech, highlighting the mental satisfaction that farming can give. Swamiji spoke about the role of organic farming in reducing various kinds of cancer. Samples of agricultural produce cultivated within the campus were displayed and many saplings were distributed. SEED volunteers are engaged in organic farming on 1500 sq. ft. land and on the college terrace. The school has won the Special Jury Award of SEED in Kerala for the year 2015. -

The Contribution of Post Colonial Indian Women Writers in Literalture

Vol.I, Issue. IV, JAN 2013 An International Refereed & Indexed Journal in Arts, Commerce & Education The Contribution of Post Colonial Indian Women Writers in Literalture Smt. Gawali M.B., Dept. of English, Shivaji Mahavidyalaya, Hingoli. Received: 13/11/2012 Reviewed: 15/11/2012 Accepted: 17/11/2012 Research Paper in English Abstract In this paper an attempt has been made to review the contribution of post-colonial Indian women writers in English Literature. These women writers have been highly acclaimed and have also been the recipients of prestigious literary prizes. In almost all the literatures of the world, the women writers are transcending the boundaries and making their presence felt on the international stage.In case of feminism, in every field and level of education now the women are seen. And they are now found in every occupation and earning as men for their Livelihood. In political and social activities also, their participation is increasing. In each and every field may be agriculture, science, Technology, social or political field, Management and Industries, Sports or cultural activities, Literature she proves her ability. The present paper focuses the contribution also for children. She wrote some critical of Indian women writers in Literature. So, studies also. we will take a review of it. Mahashweta Devi, born in a Shashi Deshpande, the daughter middle class Bengali family in 1926 in of the famous kannada dramatist and Dacca. Her work includes Hajar Churashir Sanskrit scholar, sriranga. She was born in Ma, Choti Munda evam Tar Tir, Tutu Mir. Dharwad, Karnataka. She is a winner of She gets the awards like Padma vibhushan the Sahitya Akademi Award for the novel in 2006, Ramon Magsaysay Award 1997, ‘That Long Silence’ and the Nanjangud Jnanpith Award. -

IN BA ENGLISH LANGUAGE and LITERATURE Foundation Course 2: EN 1321 Evolution of the English Language No

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA FIRST DEGREE PROGRAMME(CBCS System) in B.A. ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Revised Syllabus for 2020 Admissions onwards (Core, Complementary, Open & Elective Courses) (2020 ADMISSION ONWARDS) 1 FIRST DEGREE PROGRAMMES (CBCS System) in B.A. ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE SEMESTERS I to VI - COURSE BREAKUP [2020 Admission onwards] Sem No Course No Course Title Instructional Credits Hours 1 EN 1111.1 Language Course 1: Language Skills 5 4 1 Language Course 2: [Additional Language 1] 4 3 1 EN 1121 Foundation Course 1: Writings on 4 2 Contemporary Issues 1 EN 1141 Core Course 1: Introduction to Literary 6 4 Studies I 1 EN 1131 Complementary Course 1: Popular Literature 3 3 and Culture 1 Complementary Course 2 [External] 3 2 2 EN 1211.1 Language Course 3: Ability Enhancement 5 4 Compulsory Course- Environmental Studies and Disaster Management 2 EN 1212.1 Language Course 4: English Grammar Usage 4 3 and Writing 2 Language Course 5: [Additional Language 2] 4 3 2 EN 1241 Core Course 2: Introduction to Literary 6 4 Studies II 2 EN 1231 Complementary Course 3 : Art and Literary 3 3 Aesthetics 2 Complementary Course 4 [External] 3 3 3 EN 1311.1 Language Course 6: English for Career 5 4 3 Language Course 7:[ Additional Language 3] 5 4 3 EN 1341 Core Course 3: British Literature I 5 3 3 EN 1321 Foundation Course 2: Evolution of the 4 3 English Language 3 EN 1331 Complementary Course 5: Narratives of 3 3 Resistance 3 Complementary Course 6 [External] 3 3 4 EN 1411.1 Language Course 8: Readings in Literature 5 4 4 Language Course -

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Vishishtaaharam Abdullah, Ummi Cookery dishes Nerchakkozhi Abraham, John Stories maverick film maker Daivavela Abraham, Vinu Stories journalist and writer Nashtanayika Abraham, Vinu Novel based on the life of Rosie, Malayalam cinema's first heroine Srinivasan Oru Pusthakam Abraham, Vinu (ed) Film tributes to Malayalam film personality Srinivasan Irakal Vettayadappedumpol Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Nerinoppam Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Samaram Thanne Jeevitham Achuthanandan V.S Autobiographyformer Chief Minister of Kerala Tharippu Achuthsankar Novel set in 19th century Travancore Rashomon Agutagawa, Rayunosuki Stories translated from the Japanese by Rajan Thuvvara Balatkaram Cheyyappedunna Manass Airoor, Johnson Essay critical study of society's psychology frauds Bhakthiyum Kamavum Airoor, Johnson Essay a rationalist study into religions and their sexual motifs Hypnotism Oru Padanam Airoor, Johnson Essay rationalist and hypnotist on the science, illustrated with case studies Ormakkurippukal Ajitha Autobiographyformer Naxalite leader Aallkkoottam Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning writer Govardhanante Yatrakal Anand Novel a foray into mythology and history Marubhoomikal Undakunnath Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning work Agnisakshi Antharjanam, Lalithambika Novel made into a film by Syamaprasad Ormakallude Kudamaatom Anthicad, Sathyan Film autobiographical work of the filmmaker Sesham Vellithirayil Anthicad, Sathyan Autobiographybehind the scenes -

Personalities

PERSONALITIES ABDUL GHAF FAR KHAN (1890-1988). Also called Badshah Khan andFrontier Gandhi. A staunch Congressman and freedom fighter. He organised Khudai Khitmatgars or Red Shirts. Frst foreigner to be awarded the Bharat Ratna ABDUL KADAR MAULAVI VAKK OM (1873-1931) Social reformer who started the daily Swadeshabhimani and the magazines Muslim, Al Islam and Deepika. ABDUL KALAM , A.P.J. (b. 1931).Popularly called the Missile Man of India, was the architect of India’s various missile.He is presently Principal Scientific Adviser to the Prime Minister. Vision 2020 is a book written by Abdul Kalam and Y.S. Rajan. ABDU SALAM Pakistan’s only Nobel Prize winner for Physics in 1979. ABUL FAZAL (1561-1602) Persian scholar patronised by Akbar , wrote Akbar Nama and Ain-e-Akbari. ACHUTHA MENON, C. (1913-91) Chief Minister of Kerala 1969-70 and 1970-77. Communist Party leader and writer wrote Soviet Land, Smaranayude Edukal, Kissan Padapusthakam etc. AGASSI, ANDRE (b. 1970). US tennis player. Winner of Australian open (2001). AKBAR THE GREAT (1524-1605) full name was Jalal ud-Din Muhammad Akbar.The greatest Mughal Emperor. Born at Amarkot. Considered real founder of the Mughal empire in India.Built Fatehpur Sikri, Humayun’s Tomb at Delhi, and forts at Agra, Lahore and Allahabad. Built Ibadat Khanna for religious discussion at Fatehpur Sikri. Historians gave him the title Guardian of Mankind. AKILAN (1922-88). P.V. Akilandan, known as Akilan, was a famous Tamil poet. Won Jnanpith for Chithira Pavai. AKKITHAM (b. 1926), real name Achuthan Namboothiri, is a famous Malayalam poet. -

Current Affairs - 2018 Secretariat Asst Exam Special

CURRENT AFFAIRS - 2018 SECRETARIAT ASST EXAM SPECIAL GUIDANCE BUREAU CURRENT AFFAIRS CURRENTFOR SECRETARIAT AFFAIRS ASSt - EXAM2015 The Vayalar Award was instituted in 1977 in memory of the famous poet Vayalar Ramavarma (1928-1975) by the Vayalar Ramavarma Memorial Trust. This award is given for the best literary work in Malayalam, on October 27 (the death anniversary of Vayalar) every year. A sum of 1,00,000/-, a silver plate and certificate constitute the award. K.V. Mohan Kumar - the The first winner of the award was Lalithambika winner of the Vayalar Antharjanam for her work ‘Agnisakshi’ in 1977. Award for the year 2018 for his work ‘Ushnarashi’ 2016 U. K. Kumaran Thakshankunnu Swaroopam 2017 T. D. Ramakrishnan Sugandhi Enna Andal Devanayaki 2018 K.V. Mohan Kumar Ushnarashi Women Recipients of the Vayalar Award 1977 Lalithambika Antharjanam Agnisakshi 1984 Sugathakumari Ambalamani 1997 Madhavikutty (Kamala Surayya) Neermathalam Pootha Kalam 2004 Sarah Joseph Alahayude Penmakkal 2007 M. Leelavathy Appuvinte Anweshanam 2014 K.R.Meera Aarachaar CAREER GUIDANCE BUREAU 1 CURRENT AFFAIRS - 2018 SECRETARIAT ASST EXAM SPECIAL Vallathol Award is a literary award given by the Vallathol Sahithya Samithi for contribution to Malayalam literature. The award was instituted in 1991 in memory of Vallathol Narayana Menon, one of the modern triumvirate poets of Malayalam poetry. The award carries a cash prize of 1,11,111 and a citation. Pala Narayanan Nair was the first recipient of Vallathol Award in the year 1991. 2016 Sreekumaran Thampi 2017 Prabha Varma Pala Narayanan Nair 2018 M. Mukundan Prabha Varma The Ezhuthachan award is the highest literary honour that is given by the Kerala Sahitya Akademi, Government of Kerala.