Improving the Efficiency of Mississippi's School Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL35 Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136 Applicant Name City State Committed ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 32,793.60 ABERNATHY INDEP SCHOOL DIST ABERNATHY TX 19,385.14 ABSECON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT ABSECON NJ 13,184.40 Academia Bautista de Puerto Nuevo, Inc Rio Piedras PR 59,985.00 ACADEMIA SAN JORGE SAN JUAN PR 45,419.95 ACHIEVE CAREER PREPARATORY ACADEMY TOLEDO OH 19,926.00 ACHILLE INDEP SCHOOL DIST 3 ACHILLE OK 49,099.48 ADA PUBLIC LIBRARY ADA OH 900.00 AF-ELM CITY COLLEGE PREP CHARTER SCHOOL NEW HAVEN CT 31,630.80 AFYA PUBLIC CHARTER MIDDLE BALTIMORE MD 17,442.00 ALBANY CARNEGIE LIBRARY ALBANY MO 960.00 ALBIA COMMUNITY SCHOOL DIST ALBIA IA 26,103.24 ALBION SCHOOL DISTRICT 2 ALBION OK 16,436.20 ALEXANDRIA COMM SCHOOL CORP ALEXANDRIA IN 32,334.54 ALICE INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT ALICE TX 293,311.41 ALL SAINTS ACADEMY WINTER HAVEN FL 14,621.51 ALL SAINTS CATHOLIC SCHOOL NORMAN OK 1,075.34 ALLEGHENY-CLARION VALLEY SCH DIST FOXBURG PA 15,456.00 ALPINE COUNTY LIBRARY MARKLEEVILLE CA 16,652.16 ALPINE SCHOOL DISTRICT AMERICAN FORK UT 279,203.16 ALTOONA PUBLIC LIBRARY ALTOONA KS 856.32 ALVAH SCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 4,032.00 AMHERST COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOL DIVISION AMHERST VA 245,106.00 AMSTERDAM CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT AMSTERDAM NY 96,471.00 ANTWERP LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT ANTWERP OH 22,679.24 ANUENUE SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 5,376.00 APPLE VALLEY UNIF SCHOOL DIST APPLE VALLEY CA 409,172.44 ARCHULETA CO SCHOOL DIST 50 PAGOSA SPRINGS CO 81,774.00 -

Sex Education in Mississippi

Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work INTRODUCUTION……………………………………………………………………………....3 I. Federal Investment in Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sexuality Education Programs……………………………………………………………………………………..3 II. Adolescent Health in Mississippi……………………………………………………………..6 III. Mississippi Sex Education Law and Policy………………………………………………....…9 IV. Methodology of the Report…………………………………………………………..……...11 V. Figure 1. Map of Mississippi Public Health Districts……………………………..…………13 WHAT YOUNG PEOPLE ARE LEARNING IN MISSISSIPPI…………………..……………14 I. Federally Funded Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Programs in Mississippi …………....…..14 II. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sex Education Programs in Mississippi Public Schools……………………………………………………………………………………...22 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………………………..30 APPENDIX 1. LIST OF MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL DISTRICTS THAT RECEIVED AND RESPONDED TO OUR PUBLIC RECORDS REQUEST…………………………….....32 REFERENCES …………………………………………………………………....……………..34 2 INTRODUCTION The federal government’s heavy investment in abstinence-only-until-marriage funding over the past few decades has promulgated a myriad of state policies, state agencies, and community-based organizations focused on promoting an abstinence-only-until-marriage ideology. The trickle-down effect of the funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs and the industry it created has impacted states throughout the nation, with a disparate impact on Southern states, including -

SOS Banner June-2014

A Special Briefing to the Mississippi Municipal League Strengthen Our Schools A Call to Fully Fund Public Education Mississippi Association of Educators 775 North State Street Jackson, MS 39202 maetoday.org Keeppublicschoolspublic.org Stay Connected to MAE! Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Ocean Springs Mayor Connie Moran Moderator Agenda 1. State funds that could be used for public education Rep. Cecil Brown (Jackson) 2. State underfunding to basic public school funding (MAEP) Sen. Derrick Simmons (Greenville) 3. Kindergarten Increases Diplomas (KIDs) Rep. Sonya Williams-Barnes (Gulfport) 4. The Value of Educators to the Community Joyce Helmick, MAE President 5. Shifting the Funding of Public Schools from the State to the Cities: The Unspoken Costs Mayor Jason Shelton (Tupelo) Mayor Chip Johnson (Hernando) Mayor Connie Moran (Ocean Springs) 8. Invest in Our Public Schools to Motivate, Educate, and Graduate Mississippi’s Students Superintendent Ronnie McGehee, Madison County School District Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Sources of State Funding That Could Be Used for Public Schools As of April 2014 $481 Million Source: House of Representatives Appropriations Chairman Herb Frierson Investing in classroom priorities builds the foundation for student learning. Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com From 2009 – 2015, Mississippi’s State Leaders UNDERFUNDED* All School Districts in Mississippi by $1.5 billion! They deprived OUR students of . -

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi's Public School Districts

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi’s Public School Districts This appendix includes maps of each Mississippi public school district showing posted bridges that could potentially impact school bus routes, noted by circles. These include any bridges posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and bridges posted for gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Included with each map is the following information for each school district: the total number of bridges in the district; the number of posted bridges potentially impacting school districts, including the number of single axle postings, number of gross weight postings, and number of tandem axle bridges; the number of open bridges that should be posted according to bridge inspection criteria but that have not been posted by the bridge owners; and, the number of closed bridges.1 PEER is also providing NBI/State Aid Road Construction bridge data for each bridge posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Since the 2010 census, twelve Mississippi public school districts have been consolidated with another district or districts. PEER included the maps for the original school districts in this appendix and indicated with an asterisk (*) on each map that the district has since been consolidated with another district. SOURCE: PEER analysis of school district boundaries from the U. S. Census Bureau Data (2010); bridge locations and statuses from the National Bridge Index Database (April 2015); and, bridge weight limit ratings from the MDOT Office of State Aid Road Construction and MDOT Bridge and Structure Division. -

Delta State University

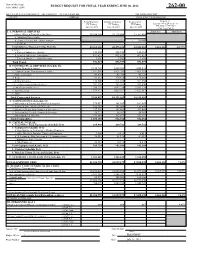

State of Mississippi BUDGET REQUEST FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2014 Form MBR-1 (2009) 262-00 DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY - ON CAMPUS CLEVELAND MS DR JOHN HILPERT AGENCY ADDRESS CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Actual Expenses Estimate Expenses Requested for Requested FY Ending FY Ending FY Ending Increase (+) or Decrease (-) FY 2014 vs. FY 2013 June 30, 2012 June 30, 2013 June 30, 2014 (Col. 3 vs. Col. 2) I. A. PERSONAL SERVICES AMOUNT PERCENT 1. Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits (Base) 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,561,810 a. Additional Compensation b. Proposed Vacancy Rate (Dollar Amount) ( 20,000) c. Per Diem Total Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,541,810 3,263,116 10.77% 2. Travel a. Travel & Subsistence (In-State) 133,503 132,153 132,153 b. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-State) 431,622 431,622 431,622 c. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-Country) 9,802 9,802 9,802 Total Travel 574,927 573,577 573,577 B. CONTRACTUAL SERVICES (Schedule B): a. Tuition, Rewards & Awards 4,130,709 4,685,048 4,685,048 b. Communications, Transportation & Utilities 1,141,810 1,421,951 1,421,951 c. Public Information 43,470 43,729 43,729 d. Rents 233,832 170,610 170,610 e. Repairs & Service 336,400 511,036 511,036 f. Fees, Professional & Other Services 791,176 763,590 763,590 g. Other Contractual Services 1,290,729 1,092,774 1,092,774 h. Data Processing 1,579,971 1,624,917 1,624,917 i. -

Auditor's 2015 Report

PUBLIC EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM OF MISSISSIPPI Schedule of Employer Allocations and Schedule of Collective Pension Amounts June 30, 2015 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) KPMG LLP Suite 1100 One Jackson Place 188 East Capitol Street Jackson, MS 39201-2127 Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Trustees Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi: We have audited the accompanying schedule of employer allocations of the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi (the System), as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. We have also audited the columns titled net pension liability, total deferred outflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, total deferred inflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, and total pension expense excluding that attributable to employer-paid member contributions (specified column totals) included in the accompanying schedule of collective pension amounts of the System as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. Management’s Responsibility for the Schedules Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these schedules in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of the schedules that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express opinions on the schedule of employer allocations and the specified column totals included in the schedule of collective pension amounts based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

06. Approval of Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation As Required by Senate Bill 2760

OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items October 18-19, 2012 OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY 06. Approval of course of action for Bolivar County School District consolidation as required by Senate Bill 2760 Recommendation: Approval Back-up material attached 1 Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation 1. State Board should review comments from the October 15th meeting offered by the affected school districts and appoint a subcommittee to hear comments from each district regarding the eventual criteria that the SBE must adopt to guide the redistricting process. The subcommittee may hold a meeting with each district for the purpose of hearing comments regarding redistricting criteria. 2. SBE should review comments from the affected districts submitted by the subcommittee. 3. SBE should review comments from the community meetings at the January 18 meeting and may adopt official criteria for reapportionment and redistricting of the new consolidated school districts. 4. Draft maps will be delivered to the districts in Bolivar County as soon as they are prepared. 5. At the February 15 meeting, SBE can review all public comments or written information submitted. 6. SBE should adopt new board member districts for North Bolivar Consolidated School District, and West Bolivar Consolidated School District at the March meeting and submit the required information to the Department of Justice. 2 MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2012 By: Senator(s) -

Prefix First Middle Last Affiliation Title Street City Zip Mary Kate Garvin Natchez-Adams School District Superintendent P.O. Bo

Prefix First Middle Last Affiliation Title street city zip Mary Kate Garvin Natchez-Adams School District Superintendent P.O. Box 1188 Natchez, MS 39121 Mike Wamsley Alcorn School District Superintendent P.O. Box 1420 Corinth, MS 38835 Lee Childress Corinth School District Superintendent 1204 North Harper Road Corinth, MS 38834 Bobby E. Whittington Amite County School District Superintendent P.O. Box 378 Liberty, MS 39645 David Spears Attala County School District Superintendent Courthouse Kosciusko, MS 39090 Dr. David Sistrunk Kosciusko School District Superintendent 206 S. Huntington Kosciusko, MS 39090 Ronny Wilkerson Benton County School District Superintendent 20 Court Street Ashland, MS 38603 Jordan Goins West Bolivar School District Superintendent P.O. Box 189 Rosedale, MS 38769 Suzanne Hawley Benoit School District Superintendent P.O. Box 189 Benoit, MS 38725 Maurice Smith North Bolivar School District Superintendent 700 Lauderdale Street Shelby, MS 38774 Reginald P. Barnes Cleveland School District Superintendent 305 Merritt Drive Cleveland, MS 38732 Charles K. Barron Shaw School District Superintendent P.O. Box 510 Shaw, MS 38773 Linder Howze-Campbell Mound Bayou Public School Superintendent Green Street Mound Bayou, MS 38762 Beth Hardin Calhoun County School District Superintendent P.O. Box 58 Pittsboro, MS 38951 Susan Murphy Carroll County School District Superintendent P.O. BOX 256 Carrollton, MS 38917 Kathy Davis Chickasaw County School District Superintendent P.O. Drawer 480 Houlka, MS 38850 Steve Coker Houston School District Superintendent P.O. Drawer 351 Houston, MS 38851 Eddie M. Prather Okolona Separate School District Superintendent P.O. Box 510 Okolona, MS 38860 Barry G. Stidham Choctaw County School District Superintendent P.O. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2014 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2014 By: Senator(s) Simmons (13th) To: Education SENATE BILL NO. 2383 1 AN ACT TO AMEND SECTION 37-7-104.1, TO AUTHORIZE CERTAIN 2 SCHOOL AND COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICTS TO OFFER EMPLOYEES A 3 SELECTION REGARDING GROUP TERM LIFE INSURANCE COVERAGE; AND FOR 4 RELATED PURPOSES. 5 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI: 6 SECTION 1. Section 37-7-104.1, Mississippi Code of 1972, is 7 amended as follows: 8 37-7-104.1. (1) In Bolivar County, Mississippi, in which 9 are located, as of January 1, 2012, six (6) school districts, 10 there shall be an administrative consolidation of all of the 11 school districts in the county into three (3) school districts as 12 follows: 13 (a) One (1) existing school district which shall be the 14 Cleveland School District; 15 (b) One (1) new consolidated school district to be 16 designated as North Bolivar Consolidated School District which 17 shall consist of the territory of the former North Bolivar School 18 District and the Mound Bayou Public School District. The central S. B. No. 2383 *SS01/R733* ~ OFFICIAL ~ G1/2 14/SS01/R733 PAGE 1 (ec\tb) 19 administrative office of the North Bolivar Consolidated School 20 District shall be located in Mound Bayou, Mississippi; and 21 (c) One (1) new consolidated school district to be 22 designated as West Bolivar Consolidated School District which 23 shall consist of the territory of the former West Bolivar School 24 District, Shaw School District and Benoit School District. -

JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS in MISSISSIPPI Geoffry Alan Haines University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2007 JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI Geoffry Alan Haines University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Haines, Geoffry Alan, "JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI" (2007). Dissertations. 1312. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1312 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI by Geoffry Alan Haines A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: December 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY GEOFFRY ALAN HAINES 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The University of Southern Mississippi JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI by Geoffry Alan Haines Abstract of -

Disproportionate Impact of K-12 School Suspension and Expulsion on Black Students in Southern States

DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT OF K-12 SCHOOL SUSPENSION AND EXPULSION ON BLACK STUDENTS IN SOUTHERN STATES Edward J. Smith and Shaun R. Harper Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education 1 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Message from U.S. Congressman Cedric Richmond (D-LA) 2 Background and Research Methods 3 - 4 School Discipline Trends Across the South 5 Southern School District Data Tables Alabama 6 - 9 Arkansas 10 - 16 Florida 16 - 18 Georgia 19 - 24 Kentucky 24 - 28 Louisiana 29 - 31 Mississippi 32 - 35 North Carolina 36 - 41 South Carolina 42 - 44 Tennessee 44 - 48 Texas 48 - 79 Virginia 79 - 83 West Virginia 84 - 85 Resources and Recommendations 86 Conclusion 87 Recommended Citation: Smith, E. J., & Harper, S. R. (2015). Disproportionate impact of K-12 school suspension and expulsion on Black students in southern states. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. The report is also available in .PDF for free download at www.gse.upenn.edu/equity/SouthernStates © 2015, The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All Rights Reserved. Opinions expressed herein belong entirely to the authors and do not necessarily represent viewpoints of the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Nationally, 1.2 million Black students were suspended from K-12 public schools in a single academic year – 55% of those suspensions occurred in 13 Southern states. Districts in the South also were responsible for 50% of Black student expulsions from public schools in the United States. This report aims to make transparent the rates School Discipline Inequities by Sex at which school discipline practices and policies impact Black students in every K-12 public school Boys were 65% of Black students suspended from district in 13 Southern states: Alabama, Arkansas, K-12 public schools in the 13 southern states. -

SCHOOL DISTRICT FIXED ASSET MANAGER Donnette Spight (Business Manager) 369-4682 4820 Aberdeen School District FAX-0987 P.O. Draw

SCHOOL DISTRICT FIXED ASSET MANAGER Donnette Spight (Business Manager) 369-4682 4820 Aberdeen School District FAX-0987 P.O. Drawer 607 Aberdeen, MS 39730 Max Young 286-5591 0200 Alcorn School District FAX-7713 P.O. Box 1420 Corinth, MS 38834 John Steele (Business Manager) 657-4361 0300 Amite County School District FAX-4291 P.O. Box 378 Liberty, MS 39645 Kathy Cadden 256-5991 4821 Amory School District FAX-4251 P.O. Box 330 Amory, MS 38821 Frances McCrory 289-2801 0400 Attala County School District FAX-2804 Courthouse Kosciusko, MS 39090 Melanie Long 365-1000 5920 Baldwyn Public School District FAX-1003 518 Hwy 45N Baldwyn, MS 38824 Garland Cuevas 467-6621 2320 Bay St. Louis-Waveland School District FAX-466-4895 201 Carrol Avenue Bay St. Louis, MS 39520 Jeanette Graham 742-3287 0612 Benoit School District FAX-3149 Box 189 Benoit, MS 38725 School/lis,e January 28, 1999 SCHOOL DISTRICT FIXED ASSET MANAGER Vicki Barber 224-6252 0500 Benton County School District FAX-3607 P.O. Box 247 Ashland, MS 38603 Jude McDonnell (228) 374-1810 2420 Biloxi Public School District FAX-1764 P.O. Box 168 Biloxi, MS 39533 Monte Lambert 728-2171 5921 Booneville School District FAX-4940 P.O. Box 358 Booneville, MS 38829 Sandy Earnest 833-6661 4320 Brookhaven School District FAX-4154 P.O. Box 540 Brookhaven, MS 39601 Teresa Dunn 412-3152 0700 Calhoun County School District FAX-3157 P.O. Box 58 Pittsboro, MS 38951 Clara Gray 859-4110 4520 Canton Public School District FAX-4023 403 E.