Shaw High School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL35 Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136 Applicant Name City State Committed ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 32,793.60 ABERNATHY INDEP SCHOOL DIST ABERNATHY TX 19,385.14 ABSECON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT ABSECON NJ 13,184.40 Academia Bautista de Puerto Nuevo, Inc Rio Piedras PR 59,985.00 ACADEMIA SAN JORGE SAN JUAN PR 45,419.95 ACHIEVE CAREER PREPARATORY ACADEMY TOLEDO OH 19,926.00 ACHILLE INDEP SCHOOL DIST 3 ACHILLE OK 49,099.48 ADA PUBLIC LIBRARY ADA OH 900.00 AF-ELM CITY COLLEGE PREP CHARTER SCHOOL NEW HAVEN CT 31,630.80 AFYA PUBLIC CHARTER MIDDLE BALTIMORE MD 17,442.00 ALBANY CARNEGIE LIBRARY ALBANY MO 960.00 ALBIA COMMUNITY SCHOOL DIST ALBIA IA 26,103.24 ALBION SCHOOL DISTRICT 2 ALBION OK 16,436.20 ALEXANDRIA COMM SCHOOL CORP ALEXANDRIA IN 32,334.54 ALICE INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT ALICE TX 293,311.41 ALL SAINTS ACADEMY WINTER HAVEN FL 14,621.51 ALL SAINTS CATHOLIC SCHOOL NORMAN OK 1,075.34 ALLEGHENY-CLARION VALLEY SCH DIST FOXBURG PA 15,456.00 ALPINE COUNTY LIBRARY MARKLEEVILLE CA 16,652.16 ALPINE SCHOOL DISTRICT AMERICAN FORK UT 279,203.16 ALTOONA PUBLIC LIBRARY ALTOONA KS 856.32 ALVAH SCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 4,032.00 AMHERST COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOL DIVISION AMHERST VA 245,106.00 AMSTERDAM CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT AMSTERDAM NY 96,471.00 ANTWERP LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT ANTWERP OH 22,679.24 ANUENUE SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 5,376.00 APPLE VALLEY UNIF SCHOOL DIST APPLE VALLEY CA 409,172.44 ARCHULETA CO SCHOOL DIST 50 PAGOSA SPRINGS CO 81,774.00 -

Sex Education in Mississippi

Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work INTRODUCUTION……………………………………………………………………………....3 I. Federal Investment in Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sexuality Education Programs……………………………………………………………………………………..3 II. Adolescent Health in Mississippi……………………………………………………………..6 III. Mississippi Sex Education Law and Policy………………………………………………....…9 IV. Methodology of the Report…………………………………………………………..……...11 V. Figure 1. Map of Mississippi Public Health Districts……………………………..…………13 WHAT YOUNG PEOPLE ARE LEARNING IN MISSISSIPPI…………………..……………14 I. Federally Funded Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Programs in Mississippi …………....…..14 II. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sex Education Programs in Mississippi Public Schools……………………………………………………………………………………...22 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………………………..30 APPENDIX 1. LIST OF MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL DISTRICTS THAT RECEIVED AND RESPONDED TO OUR PUBLIC RECORDS REQUEST…………………………….....32 REFERENCES …………………………………………………………………....……………..34 2 INTRODUCTION The federal government’s heavy investment in abstinence-only-until-marriage funding over the past few decades has promulgated a myriad of state policies, state agencies, and community-based organizations focused on promoting an abstinence-only-until-marriage ideology. The trickle-down effect of the funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs and the industry it created has impacted states throughout the nation, with a disparate impact on Southern states, including -

A Guide to Genealogical Records and Resources

Bolivar County Library System Mississippi Room – Robinson-Carpenter Public Library A Guide to Genealogical Records and Resources This guide is designed to function as a finding aid for patrons performing genealogical research in the Mississippi Room and is not a complete list of materials in the Mississippi Room. All materials (books, microfilm, VHS cassettes, maps, etc.) in the Mississippi Room are non-circulating meaning they may be used in the Mississippi Room ONLY and may not be checked out. Duplicate copies of some non-reference titles are available in the Non-Fiction section; consult the card catalog or ask the Reference Services Librarian for assistance. A microfilm reader/printer in the Mississippi Room and copy machines near the Circulation Desk are available at a cost of 25cents per page for B&W and $1.00 for color copies. Ask the Reference Services Librarian or Circulation Desk personnel for assistance with microfilm and the reader/printer. Prepared by Reference Services Revised May 30, 2013 Bolivar County Library System Robinson-Carpenter Memorial Library 104 South Leflore Avenue Cleveland, MS 38732 Phone: (662) 843-2774 Fax: (662) 843-4701 Library Website: www.bolivar.lib.ms.us Bolivar County Library System Guide to Genealogical Records and Resources – Continued 2 JOURNALS Mississippi State University. Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Cultures . 1969 through 11/30/1995 are shelved in Mississippi Room. 12/01/1995 through Present are available on the following MAGNOLIA databases: “Academic Search Premier,” “Humanities International Complete,” “Literary Reference Center,” and “MasterFILE Premier.” Journal of Mississippi History . John Edmond Gonzales, Editor. Shelved in the Mississippi Room. -

SOS Banner June-2014

A Special Briefing to the Mississippi Municipal League Strengthen Our Schools A Call to Fully Fund Public Education Mississippi Association of Educators 775 North State Street Jackson, MS 39202 maetoday.org Keeppublicschoolspublic.org Stay Connected to MAE! Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Ocean Springs Mayor Connie Moran Moderator Agenda 1. State funds that could be used for public education Rep. Cecil Brown (Jackson) 2. State underfunding to basic public school funding (MAEP) Sen. Derrick Simmons (Greenville) 3. Kindergarten Increases Diplomas (KIDs) Rep. Sonya Williams-Barnes (Gulfport) 4. The Value of Educators to the Community Joyce Helmick, MAE President 5. Shifting the Funding of Public Schools from the State to the Cities: The Unspoken Costs Mayor Jason Shelton (Tupelo) Mayor Chip Johnson (Hernando) Mayor Connie Moran (Ocean Springs) 8. Invest in Our Public Schools to Motivate, Educate, and Graduate Mississippi’s Students Superintendent Ronnie McGehee, Madison County School District Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Sources of State Funding That Could Be Used for Public Schools As of April 2014 $481 Million Source: House of Representatives Appropriations Chairman Herb Frierson Investing in classroom priorities builds the foundation for student learning. Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com From 2009 – 2015, Mississippi’s State Leaders UNDERFUNDED* All School Districts in Mississippi by $1.5 billion! They deprived OUR students of . -

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi's Public School Districts

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi’s Public School Districts This appendix includes maps of each Mississippi public school district showing posted bridges that could potentially impact school bus routes, noted by circles. These include any bridges posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and bridges posted for gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Included with each map is the following information for each school district: the total number of bridges in the district; the number of posted bridges potentially impacting school districts, including the number of single axle postings, number of gross weight postings, and number of tandem axle bridges; the number of open bridges that should be posted according to bridge inspection criteria but that have not been posted by the bridge owners; and, the number of closed bridges.1 PEER is also providing NBI/State Aid Road Construction bridge data for each bridge posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Since the 2010 census, twelve Mississippi public school districts have been consolidated with another district or districts. PEER included the maps for the original school districts in this appendix and indicated with an asterisk (*) on each map that the district has since been consolidated with another district. SOURCE: PEER analysis of school district boundaries from the U. S. Census Bureau Data (2010); bridge locations and statuses from the National Bridge Index Database (April 2015); and, bridge weight limit ratings from the MDOT Office of State Aid Road Construction and MDOT Bridge and Structure Division. -

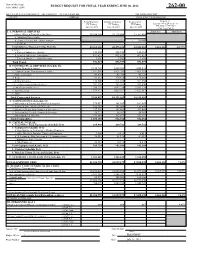

Delta State University

State of Mississippi BUDGET REQUEST FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2014 Form MBR-1 (2009) 262-00 DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY - ON CAMPUS CLEVELAND MS DR JOHN HILPERT AGENCY ADDRESS CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Actual Expenses Estimate Expenses Requested for Requested FY Ending FY Ending FY Ending Increase (+) or Decrease (-) FY 2014 vs. FY 2013 June 30, 2012 June 30, 2013 June 30, 2014 (Col. 3 vs. Col. 2) I. A. PERSONAL SERVICES AMOUNT PERCENT 1. Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits (Base) 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,561,810 a. Additional Compensation b. Proposed Vacancy Rate (Dollar Amount) ( 20,000) c. Per Diem Total Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,541,810 3,263,116 10.77% 2. Travel a. Travel & Subsistence (In-State) 133,503 132,153 132,153 b. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-State) 431,622 431,622 431,622 c. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-Country) 9,802 9,802 9,802 Total Travel 574,927 573,577 573,577 B. CONTRACTUAL SERVICES (Schedule B): a. Tuition, Rewards & Awards 4,130,709 4,685,048 4,685,048 b. Communications, Transportation & Utilities 1,141,810 1,421,951 1,421,951 c. Public Information 43,470 43,729 43,729 d. Rents 233,832 170,610 170,610 e. Repairs & Service 336,400 511,036 511,036 f. Fees, Professional & Other Services 791,176 763,590 763,590 g. Other Contractual Services 1,290,729 1,092,774 1,092,774 h. Data Processing 1,579,971 1,624,917 1,624,917 i. -

Auditor's 2015 Report

PUBLIC EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM OF MISSISSIPPI Schedule of Employer Allocations and Schedule of Collective Pension Amounts June 30, 2015 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) KPMG LLP Suite 1100 One Jackson Place 188 East Capitol Street Jackson, MS 39201-2127 Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Trustees Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi: We have audited the accompanying schedule of employer allocations of the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi (the System), as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. We have also audited the columns titled net pension liability, total deferred outflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, total deferred inflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, and total pension expense excluding that attributable to employer-paid member contributions (specified column totals) included in the accompanying schedule of collective pension amounts of the System as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. Management’s Responsibility for the Schedules Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these schedules in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of the schedules that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express opinions on the schedule of employer allocations and the specified column totals included in the schedule of collective pension amounts based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

06. Approval of Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation As Required by Senate Bill 2760

OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items October 18-19, 2012 OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY 06. Approval of course of action for Bolivar County School District consolidation as required by Senate Bill 2760 Recommendation: Approval Back-up material attached 1 Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation 1. State Board should review comments from the October 15th meeting offered by the affected school districts and appoint a subcommittee to hear comments from each district regarding the eventual criteria that the SBE must adopt to guide the redistricting process. The subcommittee may hold a meeting with each district for the purpose of hearing comments regarding redistricting criteria. 2. SBE should review comments from the affected districts submitted by the subcommittee. 3. SBE should review comments from the community meetings at the January 18 meeting and may adopt official criteria for reapportionment and redistricting of the new consolidated school districts. 4. Draft maps will be delivered to the districts in Bolivar County as soon as they are prepared. 5. At the February 15 meeting, SBE can review all public comments or written information submitted. 6. SBE should adopt new board member districts for North Bolivar Consolidated School District, and West Bolivar Consolidated School District at the March meeting and submit the required information to the Department of Justice. 2 MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2012 By: Senator(s) -

Case: 2:65-Cv-00031-DMB-JMV Doc #: 215 Filed: 05/13/16 1 of 96 Pageid #: 4392

Case: 2:65-cv-00031-DMB-JMV Doc #: 215 Filed: 05/13/16 1 of 96 PageID #: 4392 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI DELTA DIVISION DIANE COWAN, minor, by her mother PLAINTIFFS and next friend, Mrs. Alberta Johnson, et al.; FLOYD COWAN, JR., minor, by his mother and next friend, Mrs. Alberta Johnson, et al.; LENDEN SANDERS; MACK SANDERS; CRYSTAL WILLIAMS; AMELIA WESLEY; DASHANDA FRAZIER; ANGINETTE TERRELL PAYNE; ANTONIO LEWIS; BRENDA LEWIS; and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTERVENOR-PLAINTIFF V. NO. 2:65-CV-31-DMB BOLIVAR COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al. DEFENDANTS OPINION AND ORDER On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court issued the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education, holding that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954) (“Brown I”). A year later, on May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court issued a second order directing compliance with Brown I “with all deliberate speed.” Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 349 U.S. 294, 301 (1955) (“Brown II”). Ten years after Brown II, residents of Bolivar County, Mississippi, filed this now fifty-year-old action seeking the desegregation of their school system. After decades of litigation, this case is currently before the Court for the determination of an appropriate desegregation remedy for the high schools and middle schools in the Cleveland School District (“District”) in Bolivar County. Case: 2:65-cv-00031-DMB-JMV Doc #: 215 Filed: 05/13/16 2 of 96 PageID #: 4393 Upon consideration of the parties’ proposed desegregation plans, the Court concludes that, in order to achieve constitutionally-required desegregation, the District must consolidate its high schools and must consolidate its middle schools. -

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians January 2020 1 January 2020 Prepared by NSPARC / A unit of Mississippi State University 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary...............................................................................................................................1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Institutional Profile...............................................................................................................................4 Student Enrollment...............................................................................................................................6 Community College Graduates.............................................................................................................9 Employment and Earnings Outcomes of Graduates..........................................................................11 Impact on the State Economy.............................................................................................................13 Appendix A: Workforce Training.........................................................................................................15 Appendix B: Degrees Awarded............................................................................................................16 -

Improving the Efficiency of Mississippi's School Districts

#589 Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER) Report to the Mississippi Legislature Improving the Efficiency of Mississippi’s School Districts: Phase Two School districts should apply a disciplined approach of identifying their needs so that cost savings can be effectively redirected into an area that will improve the district’s efficiency and academic performance. The Legislature’s current effort to revitalize performance budgeting requires increased accountability for the efficient and effective use of public resources, including the expenditure of tax dollars by the state’s public school districts. PEER sought to identify efficiency drivers and metrics utilized by fourteen selected school districts with the purpose of compiling a list of best practices that could be shared with other districts to yield efficiency improvements. PEER had proposed that by selecting districts that exhibited low support expenditures and high academic performance, as well as those districts that exhibited high support expenditures and low academic performance, distinct practices and procedures could be identified in order to establish drivers and metrics deemed as more efficient. By using an interview protocol based on school district efficiency review processes in other states, PEER targeted nine functional areas in the fourteen selected districts: district leadership and organization, financial management, human resources, purchasing and warehousing, educational service delivery, transportation, facilities, food service, and information technology. Three major themes were exhibited within the selected school districts. Regardless of whether the district was more efficient or less efficient (as defined by PEER in this report), no distinct efficiency drivers were identified that could be implemented as best practices. -

We Gotta Work with What We Got: School and Community Factors That Contribute to Educational Resilience Among African American Students

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 We Gotta Work with What We Got: School and Community Factors That Contribute to Educational Resilience Among African American Students Denae Bradley University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Bradley, Denae, "We Gotta Work with What We Got: School and Community Factors That Contribute to Educational Resilience Among African American Students" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1556. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE GOTTA WORK WITH WHAT WE GOT”: SCHOOL AND COMMUNITY FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO EDUCATIONAL RESILIENCE AMONG AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDENTS A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology The University of Mississippi by Denae L. Bradley May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Denae Bradley All rights reserved ABSTRACT This thesis examines how Black residents in the Mississippi Delta claim and deploy agency and resiliency in a rural community context entrenched in a legacy of oppression. Black, low-income communities are implicitly labeled non-resilient when macro-level community capitals and resiliency literature are applied. However, I find that resiliency is culturally distinctive and oftentimes detected in ritual, daily processes in Black communities. This thesis rejects dominant narratives that Black communities in Mississippi are only poor, backwards, and lacking.