Presidential Authority Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

An Examination of the Call to Censure the President

S. HRG. 109–524 AN EXAMINATION OF THE CALL TO CENSURE THE PRESIDENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 31, 2006 Serial No. J–109–66 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 28–341 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas .............................. -

War Powers for the 21St Century: the Constitutional Perspective

WAR POWERS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: THE CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2008 Serial No. 110–164 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–756PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:32 May 14, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\IOHRO\041008\41756.000 Hintrel1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

Habeus Corpus and Detentions at Guantanamo Bay Hearing Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives

HABEUS CORPUS AND DETENTIONS AT GUANTANAMO BAY HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 26, 2007 Serial No. 110–152 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36–345 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:37 Jan 21, 2009 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\062607\36345.000 HJUD1 PsN: DOUGA COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California MARTIN T. MEEHAN, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RIC KELLER, Florida ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DARRELL ISSA, California LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California MIKE PENCE, Indiana STEVE COHEN, Tennessee J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia HANK JOHNSON, Georgia STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

Wikileaks, the First Amendment and the Press by Jonathan Peters1

WikiLeaks, the First Amendment and the Press By Jonathan Peters1 Using a high-security online drop box and a well-insulated website, WikiLeaks has published 75,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Afghanistan,2 nearly 400,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Iraq,3 and more than 2,000 U.S. diplomatic cables.4 In doing so, it has collaborated with some of the most powerful newspapers in the world,5 and it has rankled some of the most powerful people in the world.6 President Barack Obama said in July 2010, right after the release of the Afghanistan documents, that he was “concerned about the disclosure of sensitive information from the battlefield.”7 His concern spread quickly through the echelons of power, as WikiLeaks continued in the fall to release caches of classified U.S. documents. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton condemned the slow drip of diplomatic cables, saying it was “not just an attack on America's foreign policy interests, it [was] an attack on the 1 Jonathan Peters is a lawyer and the Frank Martin Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he is working on his Ph.D. and specializing in the First Amendment. He has written on legal issues for a variety of newspapers and magazines, and now he writes regularly for PBS MediaShift about new media and the law. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Noam N. Levey and Jennifer Martinez, A whistle-blower with global resonance; WikiLeaks publishes documents from around the world in its quest for transparency, L.A. -

Hamdan V. Rumsfeld: Establishing a Constitutional Process

S. HRG. 109–1056 HAMDAN V. RUMSFELD: ESTABLISHING A CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 11, 2006 Serial No. J–109–95 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–111 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:01 Apr 27, 2009 Jkt 043111 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43111.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:01 Apr 27, 2009 Jkt 043111 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43111.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Feingold, Hon. Russell D., a U.S. Senator from the State of Wisconsin, pre- pared statement .................................................................................................. -

<I>Gideon</I> at Guantánamo

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Gideon at Guantánamo Neal K. Katyal Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1416 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2574839 122 Yale L.J. 2416-2427 (2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons 2416.KATYAL.2427_UPDATED.DOCX7/1/2013 12:47:10 PM Neal Kumar Katyal Gideon at Guantánamo abstract. The right to counsel maintains an uneasy relationship with the demands of trials for war crimes. Drawing on the author’s personal experiences from defending a Guantánamo detainee, the Author explains how Gideon set a baseline for the right to counsel at Guantánamo. Whether constitutionally required or not, Gideon ultimately framed the way defense lawyers represented their clients. Against the expectations of political and military leaders, both civilian and military lawyers vigorously challenged the legality of the military trial system. At the same time, tensions arose because lawyers devoted to a particular cause (such as attacking the Guantánamo trial system) were asked at times to help legitimize the system, particularly when it came to decisions about whether to enter a plea to help legitimize the rickety trial system in operation at Guantánamo. author. Paul & Patricia Saunders Professor of Law, Georgetown University. -

Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak out of School Randall T

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 29 | Number 3 Article 2 2002 Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak Out of School Randall T. Shepard Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Randall T. Shepard, Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak Out of School, 29 Fordham Urb. L.J. 811 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TELEPHONE JUSTICE, PANDERING, AND JUDGES WHO SPEAK OUT OF SCHOOL Randall T. Shepard* As Americans we pride ourselves on the rule of law and its sine qua non, an independent judiciary. In The FederalistNo. 78, Alex- ander Hamilton described judicial independence as "an essential safeguard against the effects of occasional ill humors in the society."1 In the course of reaffirming the special role of judicial indepen- dence in our own society, we routinely decry the "telephone jus- tice" practiced in some parts of the world. Before the Berlin Wall came down, crimes such as "infringing on the activities of the state" served as "the fig leaves of a system that didn't disguise its real purpose: executing the wishes of the state's Communist Party leadership and their secret police."' 3 Even as the world enters the twenty-first century, there are still nations where a judge can ex- pect to receive a call from a party boss or security officer with or- ders on how to decide a case.4 While most would agree that such overt interference is the an- tithesis of judicial independence, these are the easy cases. -

Should Lawyers Be Permitted to Violate the Law?

MILITARY LAWYERING AT THE EDGE OF THE RULE OF LAW AT GUANTANAMO: SHOULD LAWYERS BE PERMITTED TO VIOLATE THE LAW? Ellen Yaroshefsky* I. INTRODUCTION “Where were the lawyers?” is the familiar refrain in the legal profession’s reflection on various corporate scandals.1 What is the legal and moral obligation of lawyers who have knowledge of ongoing illegality and criminal behavior of their clients? What should or must those lawyers do? What about government lawyers who have knowledge of such behavior? This Article considers that question in the context of military lawyers at Guantanamo—those lawyers with direct knowledge of the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo, treatment criticized throughout the world as violative of fundamental principles of international law. In essence, where were the lawyers for the government and for individual detainees when the government began to violate the most fundamental norms of the rule of law? This Article discusses the proud history of several military lawyers at Guantanamo who consistently demonstrated an unwavering commitment to the Constitution and to the rule of law. They were deeply offended about the actions of the government they served as it undermined the fundamental premises upon which the country was formed. Their jobs placed them at the edge of the rule of law and caused consistent crises of conscience.2 These military lawyers typically are not * Clinical Professor of Law and Director of the Jacob Burns Ethics Center at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Sophia Brill, a brilliant future law student, deserves significant credit for her invaluable work on this Article. -

Military Law Review

Volume 204 Summer 2010 ARTICLES LEAVE NO SOLDIER BEHIND: ENSURING ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE FOR PTSD-AFFLICTED VETERANS Major Tiffany M. Chapman A “CATCH-22” FOR MENTALLY-ILL MILITARY DEFENDANTS: PLEA-BARGAINING AWAY MENTAL HEALTH BENEFITS Vanessa Baehr-Jones PEACEKEEPING AND COUNTERINSURGENCY: HOW U.S. MILITARY DOCTRINE CAN IMPROVE PEACEKEEPING IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Ashley Leonczyk CONSISTENCY AND EQUALITY: A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING THE “COMBAT ACTIVITIES EXCLUSION” OF THE FOREIGN CLAIMS ACT Major Michael D. Jones WHO QUESTIONS THE QUESTIONERS? REFORMING THE VOIR DIRE PROCESS IN COURTS-MARTIAL Major Ann B. Ching CLEARING THE HIGH HURDLE OF JUDICIAL RECUSAL: REFORMING RCM 902A Major Steve D. Berlin READ ANY GOOD (PROFESSIONAL) BOOKS LATELY?: A SUGGESTED PROFESSIONAL READING PROGRAM FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Bovarnick THE FIFTEENTH HUGH J. CLAUSEN LECTURE IN LEADERSHIP: LEADERSHIP IN HIGH PROFILE CASES Professor Thomas W. Taylor BOOK REVIEWS Department of Army Pamphlet 27-100-204 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Volume 204 Summer 2010 CONTENTS ARTICLES Leave No Soldier Behind: Ensuring Access to Health Care for PTSD-Afflicted Veterans Major Tiffany M. Chapman 1 A “Catch-22” for Mentally-Ill Military Defendants: Plea-Bargaining away Mental Health Benefits Vanessa Baehr-Jones 51 Peacekeeping and Counterinsurgency: How U.S. Military Doctrine Can Improve Peacekeeping in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Ashley Leonczyk 66 Consistency and Equality: A Framework for Analyzing the “Combat Activities Exclusion” of the Foreign Claims Act Major Michael D. Jones 144 Who Questions the Questioners? Reforming the Voir Dire Process in Courts-Martial Major Ann B. Ching 182 Clearing the High Hurdle of Judicial Recusal: Reforming RCM 902A Major Steve D. -

September-17-CRP-Complete

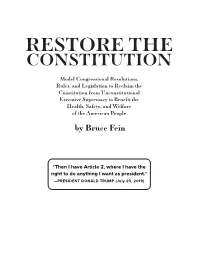

Praise for Restore the Constitution “ Bruce Fein is a no-BS constitutional textualist and originalist and, more importantly, an uncompromising constitutional patriot. He has been on the front lines of resisting the brutal Executive-branch usurpations and transgressions of the Trump presidency. In this remarkably comprehensive package, Fein offers provocative and impressive proposals not only to restore the much-trampled and much-surrendered powers of Congress but to restore the much- RESTORE THE abused liberties and rights of the people.” congressman jamin ben “jamie” raskin was also a professor of constitutional law at American University’s Washington College of Law for more than 25 years and the author of several books on law and public policy. CONSTITUTION “ Bruce Fein has meticulously diagnosed the fissures in the American Constitutional edifice and prescribed workable repairs. He brings a lifetime of scholarship and intense study to this task, Model Congressional Resolutions, focusing on recent instances of how the careful balance of power between our federal branches has come undone. From war powers to executive orders to unilateral decisions not to enforce the Rules, and Legislation to Reclaim the laws passed by Congress, Presidents have amassed power the founders never intended, and our Constitution from Unconstitutional country has suffered accordingly. Fein has devoted his prodigious talents and energy to crafting Executive Supremacy to Benefit the specific laws Congress should pass to reclaim the authority the Constitution uniquely gave it. Seldom has a constitutional text combined extensive learning with such practical applications.” Health, Safety, and Welfare tom campbell is the former Dean of Fowler School of Law, Chapman University, former Professor of Law, of the American People Stanford University, former US Congressman, and lead plaintiff in Campbell v. -

The Use of Presidential Signing Statements Hearing

S. HRG. 109–1053 THE USE OF PRESIDENTIAL SIGNING STATEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 27, 2006 Serial No. J–109–92 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–109 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:34 Apr 16, 2009 Jkt 043109 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43109.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:34 Apr 16, 2009 Jkt 043109 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43109.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas ..............................