The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Call to Censure the President

S. HRG. 109–524 AN EXAMINATION OF THE CALL TO CENSURE THE PRESIDENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 31, 2006 Serial No. J–109–66 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 28–341 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas .............................. -

War Powers for the 21St Century: the Constitutional Perspective

WAR POWERS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: THE CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2008 Serial No. 110–164 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–756PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:32 May 14, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\IOHRO\041008\41756.000 Hintrel1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

Wikileaks, the First Amendment and the Press by Jonathan Peters1

WikiLeaks, the First Amendment and the Press By Jonathan Peters1 Using a high-security online drop box and a well-insulated website, WikiLeaks has published 75,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Afghanistan,2 nearly 400,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Iraq,3 and more than 2,000 U.S. diplomatic cables.4 In doing so, it has collaborated with some of the most powerful newspapers in the world,5 and it has rankled some of the most powerful people in the world.6 President Barack Obama said in July 2010, right after the release of the Afghanistan documents, that he was “concerned about the disclosure of sensitive information from the battlefield.”7 His concern spread quickly through the echelons of power, as WikiLeaks continued in the fall to release caches of classified U.S. documents. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton condemned the slow drip of diplomatic cables, saying it was “not just an attack on America's foreign policy interests, it [was] an attack on the 1 Jonathan Peters is a lawyer and the Frank Martin Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he is working on his Ph.D. and specializing in the First Amendment. He has written on legal issues for a variety of newspapers and magazines, and now he writes regularly for PBS MediaShift about new media and the law. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Noam N. Levey and Jennifer Martinez, A whistle-blower with global resonance; WikiLeaks publishes documents from around the world in its quest for transparency, L.A. -

Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak out of School Randall T

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 29 | Number 3 Article 2 2002 Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak Out of School Randall T. Shepard Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Randall T. Shepard, Telephone Justice, Pandering, and Judges Who Speak Out of School, 29 Fordham Urb. L.J. 811 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TELEPHONE JUSTICE, PANDERING, AND JUDGES WHO SPEAK OUT OF SCHOOL Randall T. Shepard* As Americans we pride ourselves on the rule of law and its sine qua non, an independent judiciary. In The FederalistNo. 78, Alex- ander Hamilton described judicial independence as "an essential safeguard against the effects of occasional ill humors in the society."1 In the course of reaffirming the special role of judicial indepen- dence in our own society, we routinely decry the "telephone jus- tice" practiced in some parts of the world. Before the Berlin Wall came down, crimes such as "infringing on the activities of the state" served as "the fig leaves of a system that didn't disguise its real purpose: executing the wishes of the state's Communist Party leadership and their secret police."' 3 Even as the world enters the twenty-first century, there are still nations where a judge can ex- pect to receive a call from a party boss or security officer with or- ders on how to decide a case.4 While most would agree that such overt interference is the an- tithesis of judicial independence, these are the easy cases. -

September-17-CRP-Complete

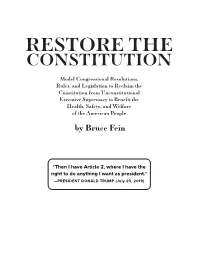

Praise for Restore the Constitution “ Bruce Fein is a no-BS constitutional textualist and originalist and, more importantly, an uncompromising constitutional patriot. He has been on the front lines of resisting the brutal Executive-branch usurpations and transgressions of the Trump presidency. In this remarkably comprehensive package, Fein offers provocative and impressive proposals not only to restore the much-trampled and much-surrendered powers of Congress but to restore the much- RESTORE THE abused liberties and rights of the people.” congressman jamin ben “jamie” raskin was also a professor of constitutional law at American University’s Washington College of Law for more than 25 years and the author of several books on law and public policy. CONSTITUTION “ Bruce Fein has meticulously diagnosed the fissures in the American Constitutional edifice and prescribed workable repairs. He brings a lifetime of scholarship and intense study to this task, Model Congressional Resolutions, focusing on recent instances of how the careful balance of power between our federal branches has come undone. From war powers to executive orders to unilateral decisions not to enforce the Rules, and Legislation to Reclaim the laws passed by Congress, Presidents have amassed power the founders never intended, and our Constitution from Unconstitutional country has suffered accordingly. Fein has devoted his prodigious talents and energy to crafting Executive Supremacy to Benefit the specific laws Congress should pass to reclaim the authority the Constitution uniquely gave it. Seldom has a constitutional text combined extensive learning with such practical applications.” Health, Safety, and Welfare tom campbell is the former Dean of Fowler School of Law, Chapman University, former Professor of Law, of the American People Stanford University, former US Congressman, and lead plaintiff in Campbell v. -

The Use of Presidential Signing Statements Hearing

S. HRG. 109–1053 THE USE OF PRESIDENTIAL SIGNING STATEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 27, 2006 Serial No. J–109–92 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–109 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:34 Apr 16, 2009 Jkt 043109 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43109.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:34 Apr 16, 2009 Jkt 043109 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43109.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas .............................. -

National Security and the First Amendment (Program) Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository IBRL Events Institute of Bill of Rights Law 1985 National Security and the First Amendment (Program) Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "National Security and the First Amendment (Program)" (1985). IBRL Events. 23. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ibrlevents/23 Copyright c 1985 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ibrlevents "N ational Security and the First Amendment" A Symposium Sponsored by the Institute of Bill of Rights Law in the College of William and Mary MarshaJl- Wythe School of Law Williamsburg, Virginia March 29 and 30, 1985 ,'National Security and the First Amendment" FRIDAY, MARCH 29 Registration and Coffee, Law School Lounge, 8:00 - 9:00 a.m. Introductory Remarks, Room 119, Law School, 9:00 a.m. William B. Spong, Jr. Dean and Director of the Institute of Bill of Rights Law Session I, Room 119,9:30 a.m. - 11:45 a.m. Principal Remarks: "Embargoes on Exports of Ideas and Information: First Amendment Issues" Robert D. Kamenshine Professor of Law Vanderbilt University Visiting Lee Professor Institute of Bill of Rights Law Panelists: Allan Adler Counsel for Center of National Security Studies American Civil Liberties Union Jerry J. Berman Legislative Counsel American Civil Liberties Union Lynn Rankin Jordan Assistant Counsel Chicago Tribune Martin Redish Professor of Law Northwestern University Elizabeth Rindskopf General Counsel National Security Agency Moderator: James W. -

Presidential Authority Transcript

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 6 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2007 Article 25 November 2007 Presidential Authority Transcript Charles Swift Bruce Fein Chief Judge Robert Lasnik Jules Lobel Deborah Pearlstein & Robert Turner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Swift, Charles; Fein, Bruce; Lasnik, Chief Judge Robert; and Deborah Pearlstein & Robert Turner, Jules Lobel (2007) "Presidential Authority Transcript," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 25. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol6/iss1/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 23 A Forum on Presidential Authority INTRODUCTION The Presidential Authority Forum took place at Seattle University School of Law on November 3, 2006. Six panelists convened to discuss issues of presidential authority that have emerged from the actions of the Bush administration. Many Americans, particularly those in the legal profession, hold a great reverence for the rule of law and the notion that no individual is immune from the protections or the constraints of the law. However, when the safety of our nation is threatened, fear dominates, and it is in this climate that our adherence to the rule of law is tested. The panelists addressed the law pertaining to a wide range of topics, including the holding of detainees at Guantánamo Bay, the treatment and interrogation of enemy combatants, torture, National Security Agency surveillance programs, the Military Commissions Act of 2006, Combatant Status Review Tribunals, and the role of Congress and the judiciary in upholding the rule of law. -

Saltzman & Evinch, P.C

FLOERAL El-fCTlOW COnMlSSlOH SALTZMAN & EVINCH, P.C. 20!iOCT-3 PM2:52 ATTORNEYS AT LAW METROPOLITAN SQUARE m 655 15TH STREET, NW, P STREET LOBBY, SUITE 225 WASHINGTON, DC 20005-5701 [email protected] [email protected] TELEPHONE (202)637-9877 FACSIMILE (202) 637-9876 WWW.TURKUW.NET September 26,2011 Via Facsimile (202) 219-3923 and U.S. Mail I Office of General Counsel 3 Federal Election Commission Attn: Jeff S. Jordan, Esq. 999 E. Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463 RE: MUR6469 Dear Mr. Jordan: Respondent Turkish Coalition of America ('TCA") hereby responds to the Compfaint filed by David Krikorian in the above-captioned matter under review.' TCA was not named as a Respondent by the complainant. But TCA was informed that the Federal Election Commission (the "EEC") considers it a subject of its investigation.^ ' Undersigned counsel declares that this reply has been submitted within the fifleen-day timeframe measured from the date of the Complaint's receipt by TCA's President, G. Lincoln McCurdy at his home address. ~ TCA respectfully requests that further mail to TCA or its officers be delivered to TCA's office at 1510 H Street, NW, Suite 900, Washington, DC 20005, with a copy sent to counsel signing herein. TCA requests that the FEC take no action against it and provides the following arguments in support based on undisputed material facts and clear law. TCA is a Massachusetts corporation, exempt from taxation under section SO I (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. It was founded to educate the general public about Turkey and Turkish Americans and to opine on critical issues to interested parties. -

Speaker Profiles and Acknowledgements a Symposium on Privacy and Security: Ucla Joins the National Debate Ucla School of Law | April 25, 2014

SPEAKER PROFILES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A SYMPOSIUM ON PRIVACY AND SECURITY: UCLA JOINS THE NATIONAL DEBATE UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW | APRIL 25, 2014 WELCOME RACHEL MORAN Dean and Michael J. Connell Distinguished Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law Rachel F. Moran is the Dean and Michael J. Connell Distinguished Professor of Law at UCLA School of Law. Prior to her appointment at UCLA, Professor Moran was the Robert D. and Leslie-Kay Raven Professor of Law at UC Berkeley School of Law. From July 2008 to June 2010, Moran served as a founding faculty member of the UC Irvine Law School. Dean Moran received her A.B. in Psychology with Honors and with Distinction from Stanford University in 1978, where she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa her junior year. She obtained her J.D. from Yale Law School in 1981, where she was an Editor of the Yale Law Journal. Following law school, she clerked for Chief Judge Wilfred Feinberg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit and worked for the San Francisco firm of Heller Ehrman White & McAuliffe. From 1993 to 1996 Moran served as chair of the Chicano/Latino Policy Project at UC Berkeley’s Institute for the Study of Social Change, and in 2003, she became the director of the Institute. In 2009, she was appointed as President of the Association of American Law Schools (AALS). JEFFREY LEWIS Chair and Associate Professor, UCLA Department of Political Science Jeffery Lewis is the Chairman and Associate Professor in the UCLA Political Science Department. Dr. -

Bruce Fein & Associates, Inc. 1025 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite

Bruce Fein & Associates, Inc. 1025 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 1000 Washington, D.C. 20036 February 5, 2009 Honorable Eric H. Holder United States Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. RE: Investigation of U.S. citizen and U.S. green card holder for genocide, war crimes, and torture against Tamils in Sri Lanka Dear Mr. Attorney General: I represent Tamils Against Genocide (TAG), a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the enforcement against a United States citizen and a United States green card holder of the Genocide Accountability Act of 2007 (GAA), the War Crimes Act, and prohibition of torture. The U.S. citizen and U.S. green card holder are Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s Defense Secretary, and Sarath Fonseka, Sri Lanka’s Army Commander, respectively. I strongly urge the Department to open a grand jury investigation into these crimes based on the enclosed three-volume, 1,000 page proposed indictment that I have prepared. I would submit that the evidence of genocide, war crimes, and torture amassed in the three volumes amply satisfies the Department’s threshold for commencing a criminal investigation. The following points, among others, demonstrate the urgency of investigating the alleged crimes: 1. The model indictment charges Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Sarath Fonseka with 12 (twelve) counts of genocide under the GAA. That legislation was spearheaded by Senator Richard Durbin (D. Illinois). It was supported by President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. The GAA is codified at 18 U.S.C. -

Anthony Bourdainof

HOW THE FOOD GURU ANTHONY ARMENIA BOURDAIN OF CNN By Dr. Ferruh DEMİRMEN* TURNED INTO AN ARMENIAN PROPAGANDIST, AND PROSPECTS OF TURKEY-ARMENIA RELATIONS reface by the author: nian genocide.” Still worse, the pro- als and summarily executed them.” This opinion piece was gram contained serious falsehoods. Anyone left was then marched prepared right after https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B0st2H8cOXw. towards the Syrian desert, “delib- the “Anthony Bour- erately starving them along the way.” The diatribe continued into the dain feat. Serj Tankian Nagorno-Karabakh issue, without He described the events as “a con- in Armenia - Parts Unknown,” TV saying a word on the 1992 Khojaly certed and organized effort to eradicate program was aired in many parts of P Massacre and the unfulfilled UN Gen- an ethnic and national group,” then the world by CNN on May 20, 2018. eral Assembly resolution on the with- concluding: “So, this is genocide, But out of respect to Mr. Bourdain drawal of all Armenian forces from right”? and his family, the publication of the article was put on hold until the occupied Azerbaijani territory. Bowing his head in agreement, his now following his tragic death in On the 1915 events in Ottoman Armenian host weighed in: “Most France in June 2018. Anatolia, Mr. Bourdain, while estimates historically put the Arme- nian losses at around 1.5 million.” Mr. Bourdain, a celebrity chef and describing himself as “a casual storyteller, when he ventured into observer,” talked more like an The misinformation and distor- his Armenia program, probably had Armenian spokesperson, claim- tions regarding the genocide accu- all the good intentions to explore ing that the “Ottomans had justified sation were shocking, but given Armenian culture and cuisine and their actions by the widely held senti- the ingrained pro-Armenian, anti- tell his story to his followers.