Retreat's Risky Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Jose Unified School District

San Jose Unified School District Project Type On-Line Date Solar 14 Different Sites beginning 2010 Willow Glen Middle School parking canopies Location Total Capacity Northern California 5.5 MW School District Enjoys Additional Savings through Sale of Renewable Energy Certificates Northern California The San Jose Unified School District is home to the largest K-12 school-district solar and energy efficiency project in the United States. The school district, which serves 32,000 students in the Silicon Valley, partnered with Chevron Energy Solutions to design and build photovoltaic projects at 14 different school sites. Through the project, San Jose Unified School District will reduce its electricity costs by 30%, and save $36 million over the life of the Voluntary purchases of Renewable project. Savings come from reduced electricity costs and also from energy certificates support generous state incentives and additional revenues from the sale of innovative and educational renewable energy certificates. The school district is also expecting projects while also saving money greater budget stability and predictability thanks to the project. for local school districts. Renewable energy generated through the project is expected to reduce carbon emissions by more than 3,100 metric tons per year. Students will also have a chance to learn first-hand about energy use and solar power generated on their own campuses with the aid of interactive kiosks designed to teach about energy use patterns, renewable energy, and conservation as well as in-class sessions and elective courses in Solar Energy Sciences. School sites include John Muir Middle School, Willow Glen Middle School, Gunderson High School, San Jose High Academy, Pioneer High School, and Leland High School. -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

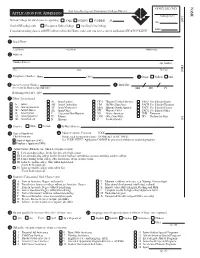

Application for Admission

OFFICE USE ONLY NAME San Jose/Evergreen Community College District APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION Colleague ID # LAST Term & College for which you are applying: FALL SPRING SUMMER 20 Date Check ONE college only Evergreen Valley College San José City College Initials If you plan on taking classes at BOTH colleges within this District, make sure you have a current application AT EACH COLLEGE 1 Legal Name Last Name First Name Middle Initial 2 Address Number & Street Apt. Number FIRST City State Zip Code 3 Telephone Number Home Other 4 Origin Walk-In Mail 5 Social Security Number 6 Birth Date (Necessary for Financial Aid applicants) MM DD YY Returning Student’s / ID # 7 Ethnic Background AL Asian/Laotian HCA Hispanic/Central America PACG Pac Islander/Guam A Asian AM Asian/Cambodian HM His/Mex Hisp/Amer PACH Pac Islander/Hawaiian AA African/American AV Asian/Vietnamese HSA Hispanic/South America PACS Pac Islander/Samoa AC Asian/Chinese AX Asian/Other HX Hispanic/Other PACX Pac Islander/Other AI Asian/Indian C Caucasian/Non-Hispanic NA Native American UNK Unknown AJ Asian/Japanese FI Filipino OTH Other Non-White XD Declined to State M.I. AK Asian/Korean H Hispanic P Pacific Islander 8 Gender Male Female 9 E-Mail Address 10 Type of Applicant 11 Major/Academic Program CODE Check if you are: If undecided, temporarily choose GENMJ.AS.1 (SJCC ONLY). Student Applicant (SAP) See CODE SHEET - Application CANNOT be processed without an academic program. Employee Applicant (EMA) 12 Admit Status (Fill in the one which best applies to you) N I am attending college for the first time after high school. -

Using MACLA's Map Tool This Paper Presents Examples of Documenting

Using MACLA’s Map Tool This paper presents examples of documenting, displaying, and discussing the social impact of MACLA through the use of geographic maps. Nine cultural arts organizations, all part of the Space for Change award program administered by Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC)1, participated in this study by providing budgetary data, programming information, and data regarding visitors and programming clientele. We provide examples of how data on community and local support can be mapped geographically and used in various settings from internal management discussions to part of grant applications. The map tool created for MACLA was developed to assist the organization in documenting and articulating its community setting and support. The map tool can be found on MACLA’s ‘front page’ of our web site at http://web.williams.edu/Economics/ArtsEcon/MACLALINC.html. There you will find a MACLA map option with an overlay of Census variables for Santa Clara County, and a map option with an overlay of Census variables for the five mile (local) area around MACLA.2 We offer the choice because one geographic region may be of more interest than the other in writing particular types of reports. Sometimes it would be more useful to show where in the county one is developing partners or attracting participants; other times the local area may be of greater interest. In this paper we will work with the Santa Clara County map, but everything presented here also applies to the 5 mile radius map. We do not provide interpretations of the many interesting aspects of MACLA’s online map here. -

Artnow 2021 Programs

ArtNow 2021 Programs Panelists Sofia Fojas Ron P. Muriera Usha Srinivasan numulosgatos.org/blog ArtNow Catalog Complimentary catalog for exhibiting Artists & Teachers Catalogs may be picked up at NUMU when we reopen! ArtNow 2021 78 Exhibiting Artists Jackson Arabaci - Los Gatos High School Aaron Kim - Palo Alto High School Isabella Prado - Palo Alto High School Erin Atluri - Los Altos High School Grace Kloeckl - Los Altos High School Ashley Qiu - Palo Alto High School Toby Britton - Los Gatos High School Savannah Knight - Los Gatos High School Jasmin Ramos - Los Altos High School Savannah Burch - Los Gatos High School Nicky Krammer - Los Altos High School Rajasri Reji - Leigh High School Ethan Burke - Leigh High School Kelly Lam - Los Altos High School Sofia Ruiz - Saint Francis High School Allison Cannard - Los Gatos High School Giselle Lebedenko - Los Gatos High School Audrey Salvador - Westmont High School Mathilde Caron - Leigh High School Lina Lee - Milpitas High School Agnes Shin - Leigh High School Vivian Cheng - Monta Vista High School Mei Lin Lee-Stahr - Branham High School Jamie Shin - Los Altos High School Defne Clarke - Homestead High School Anica Liu - Saratoga High School Jillian Silva - Saint Francis High School Lynn Dai - Saratoga High School Sydney Liu - Independence High School Gabriella Stout - Los Gatos High School Kate Davis - Los Gatos High School Kyle Lou - Archbishop Mitty Hannah Tremblay - Los Gatos High School Josh Donaker - Palo Alto High School Annalise Lowe - Leigh High School Logan Unger - Willow Glen High School -

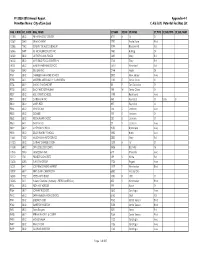

FY 2009-2010 Annual Report Permittee Name: City of San José Appendix 4-1 C.4.B.Iii.(1) Potential Facilities List

FY 2009-2010 Annual Report Appendix 4-1 Permittee Name: City of San José C.4.b.iii.(1) Potential Facilities List ORG_CODE SIC_CODE ORG_NAME ST_NUM ST_DIR ST_NAME ST_TYPE ST_SUB_TYPE ST_SUB_NUM 11385 5812 PIN HIGH GOLF CENTER 4701 N 1st St 13062 3540 3B MACHINING 2292 Trade Zone Blvd 13086 7542 SEVENTY SIX AUTO DETAILING 1099 Blossom Hill Rd 16046 3499 KC METAL PRODUCTS INC 1960 Hartog Dr 16322 5812 LA TROPICANA FOODS 1630 Story Rd 16330 5812 MI PUEBLO FOOD CENTER #4 1745 Story Rd 16331 5812 MARTIN FARNHAM SCHOOL 15711 Woodard Rd 15664 3540 K&H LAB INC 2744 Aiello Dr 9761 5812 CHARLES FANMATRE SCHOOL 2800 New Jersey Ave 9788 5411 MI TIERRA MERCADO Y CARNICERIA 1130 E Santa Clara St 9726 5812 DAKAO SANDWICHES 98 E San Salvador St 9730 5812 DAC-PHUC RESTAURANT 198 W Santa Clara St 9807 5812 HOLY SPIRIT SCHOOL 1198 Redmond Ave 9811 5812 CATERMAN INC 448 Reynolds Cir Suite B 9812 5812 MIKE'S PIZZA 497 Reynolds Cir 9846 5812 TRINE'S CAFE 146 S Jackson Ave 9853 5812 GOMBEI 193 E Jackson St 9862 5812 RESTAURANT KAZOO 250 E Jackson St 9863 5411 SHOP N GO 29 S Jackson Ave 9822 5812 MATHSON SCHOOL 2050 Kammerer Ave 9833 5812 DELOS BAGBY SCHOOL 1850 Harris Ave 11661 7530 MILLENNIUM AUTO SERVICE 2520 Story Rd 11523 5812 CATHAY CHINESE CUISINE 1339 N 1st St 11538 5812 SAN JOSE JOB CORPS 3485 East Hills Dr 11816 3540 TAGDESIGN INC. 619 University Ave 12112 1741 PIONEER CONCRETE 139 S White Rd 13600 5093 TUNG TAI GROUP 1726 Rogers Ave 16257 5411 LOS PRIMOS MEAT MARKET 1539 S Winchester Blvd 15939 5812 KIM'S CAFE-CANDESCENT 6580 Via del Oro 16248 7532 -

High Water Savings Are Killing Valley Trees

VOLUME LII, NUMBER 30 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN • LIVERMORE • PLEASANTON • SUNOL THURSDAY, JULY 23, 2015 High Water Savings Are Killing Valley Trees Find Out What's By Ron McNicoll lawns, but also the death of fruit. Removing them is a for herself, and not for the of the times, Palmer has With a Valleywide water trees that have depended on financial loss, as well. board. rngaged her own arborist; Happening conservation effort of 46 the irrigation of those lawns. Losing trees also hurts Palmer has 18 trees, in- several friends also use the percent in June, compared to Zone 7 Water Agency the community as a whole. cluding three oaks in the same advisor. Check Out Section A the same month in 2013, the board president Sarah Palm- Collectively, the cooling front yard, which she says Jackie Williams Cour- There is information on the Valley may lead or be near er, who lives in Livermore, shade can make a difference keeps the temperature on the tright, owner of a Livermore book chosen for Livermore leading the state in water said that trees all over the in a neighborhood and a city. house down by 10 or 15 de- nursery and a former Zone 7 Reads Together; reviews conservation efforts. city are dying. It's a loss to Trees give off oxygen and grees. Redwoods in the back board member, emphasized of two plays; more on the However, that might not homeowners who may de- evaporate water from their yard are mountain Sequoia, the importance of saving Berlin Wall and listings of be a good thing. -

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15 The numbers in this code list are used by both the College Board® and ACT® connect to college successTM www.collegeboard.com Alabama - United States Code School Name & Address Alabama 010000 ABBEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 411 GRABALL CUTOFF, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-2073 010001 ABBEVILLE CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, PO BOX 9, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-0009 010040 WOODLAND WEST CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 3717 OLD JASPER HWY, PO BOX 190, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005 010375 MINOR HIGH SCHOOL, 2285 MINOR PKWY, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005-2532 010010 ADDISON HIGH SCHOOL, 151 SCHOOL DRIVE, PO BOX 240, ADDISON AL 35540 010017 AKRON COMMUNITY SCHOOL EAST, PO BOX 38, AKRON AL 35441-0038 010022 KINGWOOD CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 1351 ROYALTY DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-3035 010026 EVANGEL CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, PO BOX 1670, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 010028 EVANGEL CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN, 423 THOMPSON RD, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 012485 THOMPSON HIGH SCHOOL, 100 WARRIOR DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-8700 010025 ALBERTVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 402 EAST MCCORD AVE, ALBERTVILLE AL 35950 010027 ASBURY HIGH SCHOOL, 1990 ASBURY RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-6040 010030 MARSHALL CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, 1631 BRASHERS CHAPEL RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-3511 010035 BENJAMIN RUSSELL HIGH SCHOOL, 225 HEARD BLVD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35011-2702 010047 LAUREL HIGH SCHOOL, LAUREL STREET, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010051 VICTORY BAPTIST ACADEMY, 210 SOUTH ROAD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010055 ALEXANDRIA HIGH SCHOOL, PO BOX 180, ALEXANDRIA AL 36250-0180 010060 ALICEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 417 3RD STREET SE, ALICEVILLE AL 35442 -

Of 217 11:45:20AM Club Information Report CUS9503 09/01/2021

Run Date: 09/22/2021 Key Club CUS9503 Run Time: 11:53:54AM Club Information Report Page 1 of 217 Class: KCCLUB Districts from H01 to H99 Admin. Start Date 10/01/2020 to 09/30/2021 Club Name State Club ID Sts Club Advisor Pd Date Mbr Cnt Pd Amount Kiwanis Sponsor Club ID Div H01 - Alabama Abbeville Christian Academy AL H90124 Debbie Barnes 12/05/2020 25 175.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Abbeville High School AL H87789 Valerie Roberson 07/06/2021 9 63.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Addison High School AL H92277 Mrs Brook Beam 02/10/2021 19 133.00 Cullman K00468 K0102 Alabama Christian Academy AL H89446 I Page Clayton 0 Montgomery K00174 K0108 Alabama School Of Mathematics And S AL H88720 Derek V Barry 11/20/2020 31 217.00 Azalea City, Mobile K10440 K0107 Alexandria High School AL H89049 Teralyn Foster 02/12/2021 29 203.00 Anniston K00277 K0104 American Christian Academy AL H94160 I 0 Andalusia High School AL H80592 I Daniel Bulger 0 Andalusia K03084 K0106 Anniston High School AL H92151 I 0 Ashford High School AL H83507 I LuAnn Whitten 0 Dothan K00306 K0106 Auburn High School AL H81645 Audra Welch 02/01/2021 54 378.00 Auburn K01720 K0105 Austin High School AL H90675 Dawn Wimberley 01/26/2021 36 252.00 Decatur K00230 K0101 B.B. Comer Memorial School AL H89769 Gavin McCartney 02/18/2021 18 126.00 Sylacauga K04178 K0104 Baker High School AL H86128 0 Mobile K00139 K0107 Baldwin County High School AL H80951 Sandra Stacey 11/02/2020 34 238.00 Bayside Academy AL H92084 Rochelle Tripp 11/01/2020 67 469.00 Daphne-Spanish Fort K13360 K0107 Beauregard High School AL H91788 I C Scott Fleming 0 Opelika K00241 K0105 Benjamin Russell High School AL H80742 I Mandi Burr 0 Alexander City K02901 K0104 Bessemer Academy AL H90624 I 0 Bob Jones High School AL H86997 I Shari Windsor 0 Booker T. -

End Local Hunger

TOGETHER, WE ARE CREATING A HUNGER-FREE COMMUNITY CELEBRATING YOUR COMMITMENT TO END LOCAL HUNGER SHFB.org WELCOME PROGRAM 23rd ANNUAL RECOGNITION EVENT Welcome to Second Harvest Food Bank’s WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2014 Make Hunger History Awards! at 6:00 PM In the Bay Area, we’re fortunate to have a robust Because you’re with us, we can harness our Reception & Hors d’oeuvres tech sector and a rebounding economy. But look community’s innovative spirit to uplift our neighbors beyond the rebar of new construction projects and in need. Your commitment has enabled us to 7:00 PM the highways packed with commuters, and you’ll distribute 31 million pounds of fresh produce last at see families struggling to make ends meet. fiscal year. We’re equipping our community partners Awards Program with industrial-grade refrigerators and freezers, so Kathy Jackson, CEO, Second Harvest Food Bank You might see the college student who waters they can distribute more food, safely. As one of the down his soup, hoping to stretch it a bit further. Or most efficient nonprofit organizations in the nation, the third-grader who can’t focus on her homework, 2013 Holiday Food & Fund Drive Chairs we transform a $1 donation into 2 nutritious meals. because the free school lunch is all she’s had to eat B.J. Jenkins, CEO, Barracuda Networks today. Thank you for serving as Second Harvest’s best Guy Churchward, President, Data Protection & Availability Division, EMC ambassadors, leaders, and champions. Your passion Hunger snatches away opportunity. In fact, we inspires us, every day. -

VEP MEETING September 27, 2005 GUNDERSON HIGH SCHOOL

VEP MEETING 7:30 P.M. TUESDAY September 27, 2005 GUNDERSON HIGH SCHOOL 622 Gaundabert Lane Faculty Lounge AGENDA Vector Control & West Nile Virus Presentation by Kriss Costa, Santa Clara County Department of Health. 7:30 to 8:10 p.m. John Muir Middle School A presentation by Shannon McGee, Principal. 8:10 to 8:30 p.m. Gunderson High School Construction An update by Cary Catching, Principal 8:30 to 8:40 p.m. VEP’s 2005-06 Goals & Objectives Discuss and vote on VEP’s proposed plans for the coming year. 8:40 to 8:50 pm Your Community Concerns A chance for you to tell us about your neighborhood concerns. 8:50 to 9 p.m. Our September 27 meeting -Dave Fadness What is a "vector"? What is “Vector Control”? Find out the an- swers to these and many other questions you didn't know you had at our September 27 meeting. Kriss Costa , Community Resource Specialist for the Santa Clara County Vector Control District will explain what a “vector” is and how the Vector Control District helps protect your health. Kriss will also bring us up to date regarding the West Nile virus and give us some background on this very newsworthy issue. Ms. Costa has been with the Santa Clara County Vector Control District for more than 16 years. She holds a degree in Agricultural Business and is certified by the State of California in the areas of Vector control, including vertebrate and non-vertebrate vectors, and pesticide usage. After several years as a field technician, Kriss became the first full time Vector Control community resource specialist in Califor- nia. -

View the Artnow 2021 Exhibition Catalog

new museum los gatos ArtNow 10th Annual Santa Clara County Juried High School Art Exhibition March 19 - May 9, 2021 2021 marks the 10th year of ArtNow–and ArtNow features more students, more artwork, and more diverse artistic media than ever. All of us at NUMU wish to thank visionary supporters Mike and Alyce HONORING OUR FOUNDING PARTNERS Parsons for helping us launch NUMU’s Annual Santa Clara County juried high school exhibition, now known as ArtNow, back in 2012. Mike recently reflected on the early beginnings of ArtNow, and how it’s changed over the years. When NUMU began exhibiting artwork from high school students, the museum focused on Los Gatos High School, with an occasional entry from other nearby schools. Mike noted that around the third year, the exhibition evolved into the ArtNow program we know today. The museum invited participation from all high schools in the county after understanding that no other art program showcased student artists like ArtNow. “What occurred to us was, if we were ever going to showcase as many talented artists as possible, we would need to expand. We eventually received nearly one thousand entries. We were getting very good art,” says Mike. Mike is most impressed with the quality of artwork that has been featured in ArtNow. “The entries are Mike and Alyce spectacular. Many students have gone to prestigious colleges, some focusing on art.” The talent Parsons of young artists throughout the county inspired Mike and Alyce to support the Best in Show Award, which is awarded to one student who demonstrates truly remarkable creativity and skill.