Communication Systems Amplitude Modulation (AM)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation Prof Eduardo R Miranda Varèse-Gastprofessor [email protected] Electronic Music Studio TU Berlin Institute of Communications Research http://www.kgw.tu-berlin.de/ Topics: Additive Synthesis Amplitude Modulation (and Ring Modulation) Frequency Modulation Additive Synthesis • The technique assumes that any periodic waveform can be modelled as a sum sinusoids at various amplitude envelopes and time-varying frequencies. • Works by summing up individually generated sinusoids in order to form a specific sound. Additive Synthesis eg21 Additive Synthesis eg24 • A very powerful and flexible technique. • But it is difficult to control manually and is computationally expensive. • Musical timbres: composed of dozens of time-varying partials. • It requires dozens of oscillators, noise generators and envelopes to obtain convincing simulations of acoustic sounds. • The specification and control of the parameter values for these components are difficult and time consuming. • Alternative approach: tools to obtain the synthesis parameters automatically from the analysis of the spectrum of sampled sounds. Amplitude Modulation • Modulation occurs when some aspect of an audio signal (carrier) varies according to the behaviour of another signal (modulator). • AM = when a modulator drives the amplitude of a carrier. • Simple AM: uses only 2 sinewave oscillators. eg23 • Complex AM: may involve more than 2 signals; or signals other than sinewaves may be employed as carriers and/or modulators. • Two types of AM: a) Classic AM b) Ring Modulation Classic AM • The output from the modulator is added to an offset amplitude value. • If there is no modulation, then the amplitude of the carrier will be equal to the offset. -

En 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12)

Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) HARMONISED EUROPEAN STANDARD Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) on-board vessels communications systems and equipment; Harmonised Standard covering the essential requirements of article 3.2 of the Directive 2014/53/EU 2 Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) Reference REN/ERM-TG26-136 Keywords Harmonised Standard, maritime, radio, UHF ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice The present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org/standards-search The present document may be made available in electronic versions and/or in print. The content of any electronic and/or print versions of the present document shall not be modified without the prior written authorization of ETSI. In case of any existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions and/or in print, the only prevailing document is the print of the Portable Document Format (PDF) version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: https://portal.etsi.org/People/CommiteeSupportStaff.aspx Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm except as authorized by written permission of ETSI. -

FM Stereo Format 1

A brief history • 1931 – Alan Blumlein, working for EMI in London patents the stereo recording technique, using a figure-eight miking arrangement. • 1933 – Armstrong demonstrates FM transmission to RCA • 1935 – Armstrong begins 50kW experimental FM station at Alpine, NJ • 1939 – GE inaugurates FM broadcasting in Schenectady, NY – TV demonstrations held at World’s Fair in New York and Golden Gate Interna- tional Exhibition in San Francisco – Roosevelt becomes first U.S. president to give a speech on television – DuMont company begins producing television sets for consumers • 1942 – Digital computer conceived • 1945 – FM broadcast band moved to 88-108MHz • 1947 – First taped US radio network program airs, featuring Bing Crosby – 3M introduces Scotch 100 audio tape – Transistor effect demonstrated at Bell Labs • 1950 – Stereo tape recorder, Magnecord 1250, introduced • 1953 – Wireless microphone demonstrated – AM transmitter remote control authorized by FCC – 405-line color system developed by CBS with ”crispening circuits” to improve apparent picture resolution 1 – FCC reverses its decision to approve the CBS color system, deciding instead to authorize use of the color-compatible system developed by NTSC – Color TV broadcasting begins • 1955 – Computer hard disk introduced • 1957 – Laser developed • 1959 – National Stereophonic Radio Committee formed to decide on an FM stereo system • 1960 – Stereo FM tests conducted over KDKA-FM Pittsburgh • 1961 – Great Rose Bowl Hoax University of Washington vs. Minnesota (17-7) – Chevrolet Impala ‘Super Sport’ Convertible with 409 cubic inch V8 built – FM stereo transmission system approved by FCC – First live televised presidential news conference (John Kennedy) • 1962 – Philips introduces audio cassette tape player – The Beatles release their first UK single Love Me Do/P.S. -

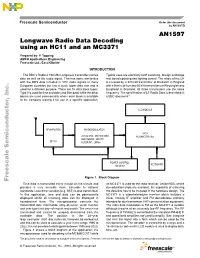

AN1597 Longwave Radio Data Decoding Using an HC11 and an MC3371

Freescale Semiconductor, Inc... microprocessor used for decoding is the MC68HC(7)11 while microprocessor usedfordecodingisthe MC68HC(7)11 2023. and 1995 between distinguish Itisnotpossible to 2022. and thiscanbeusedtocalculate ayearintherange1995to beworked out cyclecan,however, leap–year/year–start–day data.Thepositioninthe28–year available andcannotbeuniquelydeterminedfromthe transmitted and yeartype)intoday–of–monthmonth.Theisnot dateinformation(day–of–week,weeknumber transmitted the form.Themicroprocessorconverts hexadecimal displayed whilst allincomingdatacanbedisplayedin In thisapplication,timeanddatecanbepermanently standards. Localtimevariation(e.g.BST)isalsotransmitted. provides averyaccurateclock,traceabletonational Freescale AMCU ApplicationsEngineering Topping Prepared by:P. This documentcontains informationonaproductunder development. This to thecompanyleasingitforuseinaspecificapplication. available blocks areusedcommerciallywhereeachblockis other 0isusedfortimeanddate(andfillerdata)whilethe Type purpose.There are16datablocktypes. used foradifferent countriesbuthasamuchlowerdatarateandis European with theRDSdataincludedinVHFradiosignalsmany aswelltheaudiosignal.Thishassomesimilarities data using an HC11 and Longwave an Radio MC3371 Data Decoding Figure 1showsablock diagramoftheapplication; Figure data is transmitted every minuteontheand Time The BBC’s Radio4198kHzLongwave transmittercarries The BBC’s Ltd.,EastKilbride RF AMPLIFIERDEMODULATOR FM BF199 FILTER/INT.: LM358 FILTER/INT.: AMP/DEMOD.: MC3371 LOCAL OSC.:MC74HC4060 -

Amplitude Modulation(AM)

Introduction to Modulation: Amplitude Modulation(AM) Sharlene Katz James Flynn Overview Modulation Overview Basics of Amplitude Modulation (AM) AM Demonstration GRC Exercise 2 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? Example: Radio transmission Voice Microphone Transmitter Electric signal, Antenna: 20 Hz – 20 Size requirement KHz > 1/10 wavelength c 3×108 Antenna too large! 5 Use modulation to At 3 KHz: λ = = 3 =10 =100km f 3×10 transfer ⇒ .1λ =10km information to a higher frequency 3 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? (cont’d) Frequency Assignment Reduction of noise/interference Multiplexing Bandwidth limitations of equipment Frequency characteristics of antennas Atmospheric/cable properties 4 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Basic Concept of Modulation The information source Typically a low frequency signal Referred to as the “baseband signal” X(f) x(t) t f Carrier A higher frequency sinusoid baseband Modulated Modulator Example: cos(2π10000t) carrier signal Modulated Signal Some parameter of the carrier (amplitude, frequency, phase) is varied in accordance with the baseband signal 5 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Types of Modulation Analog Modulation Amplitude Modulation, AM Frequency Modulation, FM Double and Single Sideband, DSB and SSB Digital Modulation Phase Shift Keying: BPSK, QPSK, MSK Frequency Shift Keying, FSK Quadrature Amplitude Modulation, QAM 6 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Amplitude Modulation (AM) Block Diagram x(t) m x + xAM(t)=Ac [1+mx(t)]cos wct Ac cos wct Time Domain Signal information -

Generation of Carrier Signal Using Different Oscillators for ISM and Wi-Fi Band Applications

IOSR Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering (IOSR-JECE) e-ISSN: 2278-2834, p-ISSN: 2278-8735 PP 25-29 www.iosrjournals.org Generation of carrier signal using different oscillators for ISM and Wi-Fi band applications Pangavhane S.M.1, Patil P.A.2&Gite A.H.3 1,2,3(E&TC Engg. Dept.,S.I.E.RAgaskhind, SPP Univ., Pune(MS), India) Abstract : Oscillator is one of the Basic blocks in communication system. Oscillators generate the carrier signals which are to be modulated with the original message signal for transmission. The oscillators are designed mainly for ISM & Wi-Fi band applications using different technologies viz. 45nm, 65nm, 90nm.This paper deals with the most efficient design process of different types of oscillators using microwind 3.5. The different types of oscillators viz. Ring oscillator, voltage controlled oscillator are designed with minimum power consumption and minimum area on chip. Keywords –Microwind 3.5, Ring Oscillator, VCO, Frequency, Power Consumption. 1. INTRODUCTION Nowadays communication plays a vital role in human life and had become an integrated part of it. Communication includes transmission of signal from source to destination. We cannot transmit the message signal directly from the source to destination, as there is a need to modulate the signal before transmission. So we need a carrier signal of relatively high frequency to carry out the modulation process conveniently. This carrier signal will be generated by a device known as an oscillator. The communication process mainly consists of two phases, i.e. modulation at transmitter end and demodulation at receiver end. -

Mobile Tv: a Technical and Economic Comparison Of

MOBILE TV: A TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC COMPARISON OF BROADCAST, MULTICAST AND UNICAST ALTERNATIVES AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR CABLE Michael Eagles, UPC Broadband Tim Burke, Liberty Global Inc. Abstract We provide a toolkit for the MSO to assess the technical options and the economics of each. The growth of mobile user terminals suitable for multi-media consumption, combined Mobile TV is not a "one-size-fits-all" with emerging mobile multi-media applications opportunity; the implications for cable depend on and the increasing capacities of wireless several factors including regional and regulatory technology, provide a case for understanding variations and the competitive situation. facilities-based mobile broadcast, multicast and unicast technologies as a complement to fixed In this paper, we consider the drivers for mobile line broadcast video. TV, compare the mobile TV alternatives and assess the mobile TV business model. In developing a view of mobile TV as a compliment to cable broadcast video; this paper EVALUATING THE DRIVERS FOR MOBILE considers the drivers for future facilities-based TV mobile TV technology, alternative mobile TV distribution platforms, and, compares the Technology drivers for adoption of facilities- economics for the delivery of mobile TV based mobile TV that will be considered include: services. Innovation in mobile TV user terminals - the We develop a taxonomy to compare the feature evolution and growth in mobile TV alternatives, and explore broadcast technologies user terminals, availability of chipsets and such as DVB-H, DVH-SH and MediaFLO, handsets, and compression algorithms, multicast technologies such as out-of-band and Availability of spectrum - the state of mobile in-band MBMS, and unicast or streaming broadcast standardization, licensing and platforms. -

Fact Sheet No.11 Radio Frequency (RF) Emissions Classification

Fact Sheet No.11 Radio Frequency (RF) Emissions Classification The Minister responsible for Telecommunications, through the Telecommunications Unit, is charged with the responsibility of ensuring that the Radio Frequency (RF) emissions, classification adopted by Barbados conforms to well defined conventions, in accordance with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations. RF emissions are the result of radiated electromagnetic energy. They are produced by radio transmitting stations and can be utilized by radio equipment. RF emissions occur at frequencies ranging from 3kHz to 3000GHz within the radio spectrum. These emissions show differences in characteristics that are mainly dependent on their frequencies. This fact has led to the grouping together of these emissions into nine frequency bands. Different techniques are then used to propagate these various bands. Inherent characteristics dictate how these emissions can be utilized for the purpose of communication. Electrical current or voltage can be varied over time in order to produce signals which carry information. Emissions can be used to carry information by processing them in such a way as to carry signals. The process, called modulation involves the modification of the carrier by another signal or wave (the modulating wave). The resultant composite signal is the modulated wave. The process of modulation is accomplished in several ways, amongst these are - • Amplitude modulation (AM) - a type of modulation in which the amplitude of the carrier wave is varied above and below its unmodulated value by an amount proportional to the amplitude of the signal wave and at the frequency of the modulating signal. • Frequency modulation (FM) - a type of modulation in which the frequency is varied above and below its unmodulated value by an amount proportional to the amplitude of the signal wave and at a frequency of the modulating signal. -

Federal Communications Commission § 73.1590

Federal Communications Commission § 73.1590 the licensee must notify the FCC of the (2) FM stations. The total modulation date that normal operation was re- must not exceed 100 percent on peaks stored. If causes beyond the control of of frequent reoccurrence referenced to the licensee prevent restoration of the 75 kHz deviation. However, stations authorized power within 30 days, a re- providing subsidiary communications quest for Special Temporary Authority services using subcarriers under provi- (see § 73.1635) must be made to the FCC sions of § 73.319 concurrently with the in Washington, DC for additional time broadcasting of stereophonic or as may be necessary. monophonic programs may increase the peak modulation deviation as fol- [44 FR 58734, Oct. 11, 1979, as amended at 49 lows: FR 22093, May 25, 1984; 49 FR 29069, July 18, 1984; 49 FR 47610, Dec. 6, 1984; 50 FR 26568, (i) The total peak modulation may be June 27, 1985; 50 FR 40015, Oct. 1, 1985; 63 FR increased 0.5 percent for each 1.0 per- 33877, June 22, 1998; 65 FR 30004, May 10, 2000; cent subcarrier injection modulation. 67 FR 13232, Mar. 21, 2002] (ii) In no event may the modulation of the carrier exceed 110 percent (82.5 § 73.1570 Modulation levels: AM, FM, kHz peak deviation). TV and Class A TV aural. (3) TV and Class A TV stations. In no (a) The percentage of modulation is case shall the total modulation of the to be maintained at as high a level as aural carrier exceed 100% on peaks of is consistent with good quality of frequent recurrence, unless some other transmission and good broadcast serv- peak modulation level is specified in an ice, with maximum levels not to exceed instrument of authorization. -

A Short History of Radio

Winter 2003-2004 AA ShortShort HistoryHistory ofof RadioRadio With an Inside Focus on Mobile Radio PIONEERS OF RADIO If success has many fathers, then radio • Edwin Armstrong—this WWI Army officer, Columbia is one of the world’s greatest University engineering professor, and creator of FM radio successes. Perhaps one simple way to sort out this invented the regenerative circuit, the first amplifying re- multiple parentage is to place those who have been ceiver and reliable continuous-wave transmitter; and the given credit for “fathering” superheterodyne circuit, a means of receiving, converting radio into groups. and amplifying weak, high-frequency electromagnetic waves. His inventions are considered by many to provide the foundation for cellular The Scientists: phones. • Henirich Hertz—this Clockwise from German physicist, who died of blood poisoning at bottom-Ernst age 37, was the first to Alexanderson prove that you could (1878-1975), transmit and receive Reginald Fessin- electric waves wirelessly. den (1866-1932), Although Hertz originally Heinrich Hertz thought his work had no (1857-1894), practical use, today it is Edwin Armstrong recognized as the fundamental (1890-1954), Lee building block of radio and every DeForest (1873- frequency measurement is named 1961), and Nikola after him (the Hertz). Tesla (1856-1943). • Nikola Tesla—was a Serbian- Center color American inventor who discovered photo is Gug- the basis for most alternating-current lielmo Marconi machinery. In 1884, a year after (1874-1937). coming to the United States he sold The Businessmen: the patent rights for his system of alternating- current dynamos, transformers, and motors to George • Guglielmo Marconi—this Italian crea- Westinghouse. -

Performance of Coherent Direct Sequence Spread Spectrum

PERFORMANCE OF COHERENT DIRECT SEQUENCE SPREAD SPECTRUM FREQUENCY SHIFT KEYING A thesis presented to the faculty of the Russ College of Engineering and Technology of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Sudhir Kumar Sunkara November 2005 This thesis entitled PERFORMANCE OF COHERENT DIRECT SEQUENCE SPREAD SPECTRUM FREQUENCY SHIFT KEYING by SUDHIR KUMAR SUNKARA has been approved for the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Russ College of Engineering and Technology by David W. Matolak Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Dennis Irwin Dean, Russ College of Engineering and Technology SUNKARA, SUDHIR KUMAR. M.S. November 2005. Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Performance of Coherent Direct Sequence Spread Spectrum Frequency Shift Keying (83pp.) Director of Thesis: David W. Matolak We analyze the performance of a multi-user coherently-detected direct sequence spread spectrum frequency shift keying modulated system. Detection is done with respect to an arbitrary user. We derive bit error probability expressions for both synchronous and asynchronous systems. For the synchronous system, we analyze different variations of the system in order to ensure orthogonality. Orthogonality is achieved via both frequency separation and orthogonal codes. In the asynchronous system, orthogonality is achieved only through frequency separation. The channel impairments considered were additive white Gaussian noise and multi-user interference. We then extend this to a Rayleigh fading channel, and provide analytical and simulation results for single user and multi- user cases. We also analyzed the spectral characteristics of these systems. Approved: David W. Matolak Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr.