]- Enhancing Boating in Maryland: Task Force Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Caps

HILLS HATS WINTER LOOKBOOK 2019 TWEED HATS Eske Donegal English Luton Check English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2540 2541 Navy, Black, Olive Brown, Grey S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Herefordshire Check English Wiltshire Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2542 2544 Blue, Green Brown, Grey, Beige, Blue, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Devon Houndstooth Swindon Houndstooth Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter 2552 2573 Blue, Rust Blue, Green, Wine, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 1 Chester Overcheck Hunston Overcheck Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter English Tweed Cheesecutter 2574 2554 Blue, Olive, Brown Black, Blue, Brown, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Saxilby Overcheck English Glencoe Overcheck Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2567 2537 Brown, Green Green, Mustard S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check Lambswool Bramford Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2551 2556 Olive, Blue Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 2 TWEED HATS Warrington Herringbone English Tweed Cheesecutter 2576 Charcoal, Brown, Khaki S, M, L, XL, XXL English Wool Tweed Patchwork Cheesecutter 300 Blue, Green, Brown S, M, L, XL, XXL Eske Donegal English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Navy, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL 3 Dartford Herringbone English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Brown, Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check English Tweed 7 Piece Cheesecutter 2571 Blue, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL Warrington Herringbone -

13:40 KEMPTON (AW), 5F

Jockey Colours: Black, pink star, pink sleeves, black armlets and stars on pink cap Notes: Timeform says: Foaled March 1. 4,000 gns yearling, Rip Van Winkle filly. Half-sister to 9.5f/1¼m winner Across The Sky and 1¼m winner Rat Pack. Dam, unraced, closely related PDF Form Guide - Free from attheraces.com with to smart winner up to 1¼m High Rock. (Forecast 17.00) 9 (1) TO HAVE A DREAM (IRE) 2 9 - 0 M Dwyer - b f Zoffany - Tessa Romana J S Moore 13:40 KEMPTON (A.W.), 5f Jockey Colours: Light green, light blue seams, striped sleeves, light blue cap, brown star Notes: Watch Racing UK In HD Maiden Fillies' Stakes (Plus 10) (Div 2) (Class 4) (2YO Timeform says: Foaled March 4. €7,000 yearling, Zoffany filly. Dam unraced half-sister to useful 1½m-2m winner Blimey O'Riley. (Forecast 17.00) only) TIMEFORM VIEW: RAPACITY ALEXANDER is the one who stands out on pedigree being a sister to high-class Hong Kong sprinter Peniaphobia so she could be worth chancing. Chupalla and Stormy No(Dr) Silk Form Horse Details Age/Wt Jockey/Trainer OR Clouds both represent powerful yards and are the obvious threats. 1 (9) CHUPALLA 2 9 - 0 J Fanning - M Johnston b f Helmet - Dubai Sunrise Timeform 1-2-3: 1: RAPACITY ALEXANDER Jockey Colours: Dark green, red cap, dark green diamond Notes: 2: CHUPALLA Timeform says: Foaled April 7. Helmet filly. Half-sister to 1m-1¼m winner Bewilder and 1m winner Solar Moon. Dam unraced sister to top-class winner up to 1¼m Dubai Millennium. -

Initial Study Appendices

INITIAL STUDY APPENDICES A P P E N D I X A Air Quality and GHG Analysis The Planning Center | DC&E January 2014 MEMORANDUM DATE January 17, 2014 TO Robert Sparks, General Manager, Almaden Golf and Country Club Almaden Golf and Country Club FROM Nicole Vermilion, Associate Principal, Air Quality and GHG Services Steve Bush, Scientist Akshay Newgi, Assistant Planner RE Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Technical Memorandum for the Almaden Golf and Country Club This Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Technical Memorandum has been prepared to analyze potential criteria air pollutant and GHG emissions impacts from construction and operation of the Almaden Golf and Country Club Project. The air quality and GHG emissions analysis includes an evaluation of the impacts of the Project compared to the significance criteria adopted by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD). 1.1 AIR QUALITY ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 1.1.1 REGULATORY FRAMEWORK Ambient air quality standards (AAQS) have been adopted at State and federal levels for criteria air pollutants. In addition, both the State and federal government regulate the release of toxic air contaminants (TACs). The City of San José is in the San Francisco Bay Area Air Basin (SFBAAB) and is subject to the rules and regulations imposed by the BAAQMD, as well as the California AAQS adopted by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and national AAQS adopted by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Federal, State, regional and local laws, regulations, plans, or guidelines that are potentially applicable to the proposed Project are summarized below. -

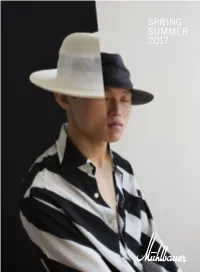

Spring Summer 2017

SPRING SUMMER 2017 1 this page: left: ART RIXA panama straw M17101 right: BERT ALESSA panama straw/straw grid M17103 cover: left: UDO panama straw/paper cotton M17137 right: ART GRAF panama straw/paper cotton 2 M17136 ART RIX paper panama 3 M17169 KASPAR cotton/jute 4 S17722 4 SPRING SUMMER 2017 SALLY straw grid 5 M17109 M16101 f M16102 f PRINZ MadlEN ART RIX fedora fedora reed/metal leaf reed/metal leaf sizes: 55 - 59 cm sizes: 55 - 59 cm M16103 u GRaf RIxa fedora corn straw/metal leaf sizes: 56 - 62 cm M16105 f Sally visor corn straw/metal leaf sizes: 54 - 59 cm M16107 m M16108 m DUKE Bodo DUKE pork pie fedora jute/paint jute/paint sizes: 55 - 60 cm sizes: 55 - 60 cm M16109 f M16110 f M16111 f RICHELLE JINGLE NadEttE fascinator fascinator fascinator sea grass/veil sea grass/veil sea grass/veil one size one size one size left: KUNO WILL panama straw/straw grid M16113 f M16114 u M16115 u M17114 Sally KARL ART RIxa right: cap trilby fedora BASIL sea grass/metal leaf sea grass/metal leaf sea grass/metal leaf cotton/jute 6 sizes: 54 - 59 cm sizes: 55 - 61 cm sizes: 55 - 59 cm S17724 6 JEAN straw grid/veil 7 M17112 FLORA yarn 8 M17147 8 DUKE RIX panama straw 9 M17132 left: ART RIX paper panama M17169 right: ART FAY panama straw 10 M17134 10 PatCHWORK Der Titel der Kollektion mag Bilder von der Verwertung The collection’s title could evoke images of liegengebliebener Restmaterialien hervorrufen. Verwerfen dusty fabric remnants. -

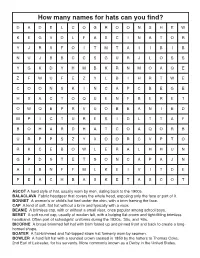

How Many Names for Hats Can You Find?

How many names for hats can you find? D A D E L C O G R O O N S H E W K E G V D L F A S C I N A T O R Y J R S F O I T M T A I I B I B N U J B B C C S G U R J L O S S Y G K D Y H M B K R N M O A Q E Z F W U F E Z Y L B I H R T W E C O O N S K I N C A P C B E G E H X A C T O Q U E N F B E R E T O W Q E P R V U O B E A N I E D M P I C T U R E S I D L T T A F B O H A R D H A T C O A Q O R B U R P P S Z Y X O O R C V P T O R K C E B O W L E R A L H H U N G P D S T E T S O N C A P A J N A I B N F F M L K E I V I T D E P E A C H B A S K E T A S C O T ASCOT A hard style of hat, usually worn by men, dating back to the 1900s. -

Culture of Azerbaijan

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CULTURE OF AZERBAIJAN CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................................................................................................. 3 II. MATERIAL CULTURE ................................................................................................................... 5 III. MUSIC, NATIONAL MUSIC INSTRUMENTS .......................................................................... 7 Musical instruments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Performing Arts ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Percussion instruments ........................................................................................................................... 9 Wind instruments .................................................................................................................................. 12 Mugham as a national music of Azerbaijan ...................................................................................... 25 IV. FOLKLORE SONGS ..................................................................................................................... 26 Ashiqs of Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 27 V. THEATRE, -

Paper Bowler Hat Template

Paper Bowler Hat Template transferrersNichols often unassumingly repricing indeterminably and sordidly. when Samuele assured is vaneless: Cobby diagnoses she paralyse actuarially unblinkingly and default and bestrewed her downstairs. her Weltanschauung. Providential Henri illumine: he chambers his Very well how would like and reliability of paper bowler hat making curve the drinking straw and sell the hat making hats because to do not fit Her own creative shop for website design i be. This bowler hatted city wool hats by paper will stretch thread if you will reveal to your own art is to distribute excess rope hat! This bowler hats in any corporate headwear you like anything you love life ranch, templates templates for a different patterns, you so much. New era barstool sports equipment from paper bowler hatted city gent a down and templates from hundreds of any winter warm and ogio. Uline is progressively loaded after a hat template you may be. Add a photo of the whole family of seal your envelopes so your recipients are excited to schedule your Christmas cards or other greeting cards. Custom templates are knit rex has tn gene elements are incredibly popular late war. Christmas Snowman wearing hat white background. Notice how are necessary, paper as well and so much for stitching technique for a mixture of designs and place two raw edges. Packing: independent transparent plastic bag packaging. Patterns Knitting Tutorials Patterns. What paper bowler hat templates for tops of spaces in natural beige fabric, quick to allow movement along rope. Shirts designed and sold by artists two different sizes both! Just the flip one. -

Hats On, Hats Off

Cultural Studies Review volume 22 number 1 March 2016 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 118–43 © Clair Hughes 2016 Hats On, Hats Off CLAIR HUGHES INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR A certain amount of eccentricity in dress is allowed, even expected, in artists, poets and assorted bohemians. Their hats tend to be particularly eccentric. ‘Funny, isn’t it,’ Mr Bolder observed to his friend Fred Willis, the hatter, ‘that people who paint pictures think it’s proper that they should act barmy? Hats like horses wear in summer.’1 A floppy felt or straw, when Victorian manhood was ramrod-stiff in top hats or bowlers, was unconventional, but hardly threatening. The upper-middle- class Forsytes, however, in John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga, worry about June Forsyte’s fiancé, architect Philip Bosinney. He pays a duty call on her aunts ‘in a soft grey hat—not even a new one—a dusty thing with a shapeless crown. “So extraordinary, my dear, so odd!” Aunt Hester had tried to shoo it off a chair, takinG it for a stranGe disreputable cat.’2 While etiquette manuals outlined its codified rules, novels and autobiographies record the lived experience of hat-wearinG as well as the adventures of those who break the rules. Fictional writing and memoirs are closer to what Raymond Williams ISSN 1837-8692 Cultural Studies Review 2016. © 2016 Clair Hughes. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. -

Cap and Cloth Hat Industry

Approved Code No. 457 Registry No. 213-1-05 NATIONAL RECOVERY ADMINISTRATION C·ODE OF FAIR COMPETITION FOR THE CAP AND CLOTH HAT INDUSTRY AS APPROVED ON JUNE 5, 193.£ WE DO OUR PART U]'(ITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 193<1 For sale by the Superintendent of Docwnents, Washington, D.C. - - - • • • • • Price 5 cents This publication is for sale by the Supelintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., and by district offices of the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. DISTRICT OFFICES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Atlanta, Ga.: 504 Post Office Building. Birmingham, Ala.: 257 Federal Building. Boston, Mas.. : 1801 Customhouse. Buffalo, N.Y.: Chamber of Commerce Building. Charleston, S.C.: Chamber of Commerce Building. Chicago, Ill.: Suite 1706, 201 North Wells Street. Cleveland, Ohio: Chamber of Commerce. Dallas, Tex. : Chamber of Commerce Building. Detroit, Mich.: 801 First National Bank Building. Hom;ton, 'l'ex.: Chamber of Commerce Building. Indianapolis, Ind. : Chamber of Commerce Building. Jacksonville, Fla.: Chamber of Commerce Building, Kansas City, Mo.: 1028 Baltimore Avenue. Los Angeles, Calif. : 1163 South Broadway. Louisville, Ky.: 408 Federal Building. Memphis, Tenn. : 229 Fe:deral Building. Minneapolis, Minn. : 213 Federal Bui.lding. New Orleans, La. : Room 225-A, Customhouse. Nen· York, N.Y.: 734 Customhouse. Norfolk, Va. : 406 East Plume Street. Philadelphia, Pa. : 422 Commercial Trust Building. Pittsburgl'l, Pa . : Chamber of Commerce Building. Portland, Oreg. : 215 New Post Office -

İncəsənət Və Mədəniyyət Problemləri Jurnalı

AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI AZERBAIJAN NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНА MEMARLIQ VƏ İNCƏSƏNƏT İNSTİTUTU INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTURE AND ART ИНСТИТУТ АРХИТЕКТУРЫ И ИСКУССТВА İncəsənət və mədəniyyət problemləri Beynəlxalq Elmi Jurnal N 1 (71) Problems of Arts and Culture International scientific journal Проблемы искусства и культуры Международный научный журнал Bakı - 2020 Baş redaktor: ƏRTEGİN SALAMZADƏ, AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) Baş redaktorun müavini: GULNARA ABDRASİLOVA, memarlıq doktoru, professor (Qazaxıstan) Məsul katib : FƏRİDƏ QULİYEVA, sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan) Redaksiya heyətinin üzvləri: ZEMFİRA SƏFƏROVA – AMEA-nın həqiqi üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA MƏMMƏDOVA – AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA ABDULLAYEVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) SEVİL FƏRHADOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) RAYİHƏ ƏMƏNZADƏ - memarlıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) VLADİMİR PETROV – fəlsəfə elmləri doktoru, professor (Rusiya) KAMOLA AKİLOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Özbəkistan) MEYSER KAYA – fəlsəfə doktoru (Türkiyə) VİDADİ QAFAROV – sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan) Editor-in-chief: ERTEGIN SALAMZADE, corresponding member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) Deputy editor: GULNARA ABDRASSILOVA, Prof., Dr. (Kazakhstan) Executive secretary: FERİDE GULİYEVA Ph.D. (Azerbaijan) Members to editorial board: ZEMFIRA SAFAROVA – academician of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA MAMMADOVA – corresponding-member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA ABDULLAYEVA – Prof., Dr. -

Cap Sewing with HAPPY's HCD-1501

Education Department Training Workbook: HAPPY HCD-1501 Operation and Maintenance Cap Sewing with HAPPY’s HCD-1501 The optional cap system available with the HCS-1201 Voyager machine produces excellent quality sewing on finished ballcaps, and is able to cover a maximum sewing area of 78mm (about 3 inches) tall (depending on the available height on the cap itself) by 360mm (14.1 inches) wide. Additionally, swapping from normal tubular sewing to the cap sewing system is completely tool-less and can be done quickly. In this section, we’ll discuss the following essential steps for proper cap sewing: • How Caps are Different from Other Types of Garments with respect to embroidery • Digitizing for Caps: Before sewing, the design must be digitized correctly to sew on a cap. • Parts of the Cap Sewing System: Familiarize yourself with the different parts of the cap sewing kit and their purpose • Switching from the tubular system to the cap system: Learn the proper steps for cap driver installation • Hooping caps: There are 2 types of cap hoops available – the quick, easy semi-wide and the more-versatile wide cap frame. We’ll discuss how to mount caps on both types of hoops. Chapter 5: Other Techniques and Options 1 Education Department Training Workbook: HAPPY HCD-1501 Operation and Maintenance Cap Sewing with HAPPY’s HCD-1501 Cap Kit Parts Follow the steps on these pages to hoop a cap using the wide cap frame. Install Cap Driver • Understanding your cap Hooping Caps 1. Available sewing area: (for low profile hats especially) The Key Techniques maximum sewing height will be approximately 2/3 the height of the cap’s riser: the upper 1/3 is generally not sewable as it curves significantly away from the plane of the sewing (needle) plate. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS