Boston Review | Tim Riley Reviews Greil Marcus's Bob Dylan 4/6/09 3:40 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

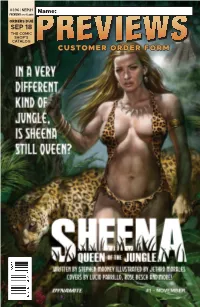

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Matrices of 'Love and Theft': Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan

Twentieth-Century Music 18/2, 249–279 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572221000013 Matrices of ‘Love and Theft’: Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan MIMI HADDON Abstract This article uses Joan Baez’s impersonations of Bob Dylan from the mid-1960s to the beginning of the twenty-first century as performances where multiple fields of complementary discourse con- verge. The article is organized in three parts. The first part addresses the musical details of Baez’s acts of mimicry and their uncanny ability to summon Dylan’s predecessors. The second con- siders mimicry in the context of identity, specifically race and asymmetrical power relations in the history of American popular music. The third and final section analyses her imitations in the context of gender and reproductive labour, focusing on the way various media have shaped her persona and her relationship to Dylan. The article engages critical theoretical work informed by psychoanalysis, post-colonial theory, and Marxist feminism. Introduction: ‘Two grand, Johnny’ Women are forced to work for capital through the individuals they ‘love’. Women’s love is in the end the confirmation of both men’s and their own negation as individ- uals. Nowadays, the only possible way of reproducing oneself or others, as individuals and not as commodities, is to dam this stream of capitalist ‘love’–a ‘love’ which masks the macabre face of exploitation – and transform relationships between men and women, destroying men’s mediatory role as the representatives of state and capital in relation to women.1 I want to start this article with two different scenes from two separate Bob Dylan films. -

Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 Page 1

AIN 'T GOIN ' NOWHERE BOB DYLAN 1967 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , RELEASES , TAPES & BOOKS . © 2001 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 page 1 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 2 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE ................................................................................................... 2 3 CALENDAR .............................................................................................................................. 2 4 RECORDINGS ......................................................................................................................... 3 5 JOHN WESLEY HARDING ................................................................................................... 3 6 SONGS 1967 .............................................................................................................................. 5 7 SOURCES .................................................................................................................................. 6 8 SUGGESTED READINGS ...................................................................................................... 7 8.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... -

Bob Dylan Musician, Keith Negus. This File Contains the Pre-Proof

Bob Dylan Musician, Keith Negus. This file contains the pre-proof versions of Chapter One and Chapter Five from Bob Dylan, presented here in this format with the permission of Equinox Publishing. I have called this text Bob Dylan Musician because this was the original agreed title of the book right up to the moment just before publication when pressure from the US publisher resulted in the term ‘musician’ being reluctantly (from my perspective) expunged from the title. That word – musician – was there to concisely signal how my approach differs from most other books on Bob Dylan. I am interested in his work and practice as a musician, rather than his lyrics as poetry or the relationship between his biography and musical art. The book contains five chapters, so these two chapters introduce and conclude the study. If anyone would like electronic copies of additional chapters I am happy to provide these, as long as they are used only for research and teaching. Keith Negus June 2013 CHAPTER ONE Surroundings On 31 October 1964 Bob Dylan performed at the Philharmonic Hall in New York City, just two years after signing a recording contract and with four albums already released. Having quickly gained recognition as a folk ‘protest singer’ he was rapidly moving away from songs of social commentary and ‘finger pointing’. Dylan was beginning to use the popular song in a new and radical manner to explore more internal or subjective experiences, whilst experimenting with the sound, meaning and rhythm of words. Within three months, when recording his fifth album, no longer performing alone with acoustic guitar and harmonica, he was beginning to create an abrasive yet ethereal sonority, mixing the acoustic and electric textures of folk, electric blues, rock’n’roll, gospel, country and pop. -

Political Political Theory

HarvardSpring 8 Summer 2016 Contents Trade................................................................................. 1 Philosophy | Political Theory | Literature ...... 26 Science ........................................................................... 33 History | Religion ....................................................... 35 Social Science | Law ................................................... 47 Loeb Classical Library ..............................................54 Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library ...................... 56 I Tatti Renaissance Library .................................... 58 Distributed Books ...................................................... 60 Paperbacks .....................................................................69 Recently Published ................................................... 78 Index ................................................................................79 Order Information .................................................... 80 cover: Detail, “Erwin Piscator entering the Nollendorftheater, Berlin” by Sasha Stone, 1929. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art. Gift of Henrick A. Berinson and Adam J. Boxer; Ubu Gallery, New York. 2007.3.2 inside front cover: Shutterstock back cover: Howard Sokol / Getty Images The Language Animal The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity Charles Taylor “There is no other book that has presented a critique of conventional philosophy of language in these terms and constructed an alternative to it in anything like this way.” —Akeel -

SEPTEMBER ONLY! 17 & 18, 2016 Long Beach Convention Center SEE NATHAN FILLION at the PANEL!

LONG BEACH COMIC CON LOGO 2014 SAT SEPTEMBER ONLY! 17 & 18, 2016 Long Beach Convention Center SEE NATHAN FILLION AT THE PANEL! MEET LEGENDARY CREATORS: TROY BAKER BRETT BOOTH KEVIN CONROY PETER DAVID COLLEEN DORAN STEVE EPTING JOELLE JONES GREG LAND JIMMY PALMIOTTI NICK SPENCER JEWEL STAITE 150+ Guests • Space Expo Artist Alley • Animation Island SUMMER Celebrity Photo Ops • Cosplay Corner GLAU SEAN 100+ Panels and more! MAHER ADAM BALDWIN WELCOME LETTER hank you for joining us at the 8th annual Long Beach Comic Con! For those of you who have attended the show in the past, MARTHA & THE TEAM you’ll notice LOTS of awesome changes. Let’s see - an even Martha Donato T Executive Director bigger exhibit hall filled with exhibitors ranging from comic book publishers, comic and toy dealers, ENORMOUS artist alley, cosplay christine alger Consultant corner, kids area, gaming area, laser tag, guest signing area and more. jereMy atkins We’re very proud of the guest list, which blends together some Public Relations Director of the hottest names in industries such as animation, video games, gabe FieraMosco comics, television and movies. We’re grateful for their support and Marketing Manager hope you spend a few minutes with each and every one of them over DaviD hyDe Publicity Guru the weekend. We’ve been asked about guests who appear on the list kris longo but who don’t have a “home base” on the exhibit floor - there are times Vice President, Sales when a guest can only participate in a signing or a panel, so we can’t CARLY Marsh assign them a table. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Dr. Eva Cherniavsky, Chair Dr. Habiba Ibrahim Dr. Chandan Reddy Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 J.E. Jed Murr University of Washington Abstract The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Eva Cherniavksy English This dissertation project investigates some of the ways histories of racial violence work to (de)form dominant and oppositional forms of common sense in the allegedly “post-racial” United States. Centering “culture” as a terrain of contestation over common sense racial meaning, The Unquiet Dead focuses in particular on popular cultural repertoires of narrative, visual, and sonic enunciation to read how histories of racialized and gendered violence circulate, (dis)appear, and congeal in and as “common sense” in a period in which the uneven dispensation of value and violence afforded different bodies is purported to no longer break down along the same old racial lines. Much of the project is grounded in particular in the emergent cultural politics of race of the early to mid-1990s, a period I understand as the beginnings of the US “post-racial moment.” The ongoing, though deeply and contested and contradictory, “post-racial moment” is one in which the socio-cultural valorization of racial categories in their articulations to other modalities of difference and oppression is alleged to have undergone significant transformation such that, among other things, processes of racialization are understood as decisively delinked from racial violence. -

“You've Been with the Professors”: Influence, Appropriation, and The

۰ૡഀ “You’ve Been with the Professors”: Influence, Appropriation, and the Cultural Interpretation of Bob Dylan Sean Wilentz, Bob Dylan in America. New York: Doubleday, 2010. 390 pp., 99 bw illus., index. Greil Marcus, Bob Dylan: Writings 1968-2010. New York: PublicAffairs, 2010. xx, 483 pp, 14 bw illus., index. Jeffrey L. Meikle )Vojwfstjuz!pg!Ufybt!bu!Bvtujo* American Studies as a discipline, at least as practiced in the United States, has sometimes attracted criticism that it encourages narcissistic navel-gazing by a culture whose socioeconomic base is affluent enough to afford that luxury. This complaint is especially prevalent in attacks on scholars who direct their attention to popular examples of the products of mass culture. A former colleague of mine, for example, often aimed sarcastic barbs at people who “write about their record collections.” At the least, he believed, such unprofessional scholars are too lazy to look beyond narrow personal interests; at worst, they project their own guilty pleasures onto the +FGGSFZ-.FJLMF larger culture in a solipsistic gesture motivated by self-justification. Although my colleague’s opinion reflected a bitter, ultimately dismissive attitude toward recent scholarship on contemporary mass culture, there is indeed a gray area where celebrity worship, fanboy obsession, and personal desire to claim cultural capital may blur traditional notions of scholarship’s neutral objectivity. Attempts to overcome such attacks often seek to prove by applying audience or reception theory that popular culture products do have substantive impact on the lives of those who consume them. That defense may appear questionable not only because reception is notoriously difficult to measure but also because critical theory’s densely-worded, jargon-laden arguments may seem like self-serving obfuscation to readers already inclined to be skeptical of serious claims for popular or mass culture. -

8 Can a Fujiyama Mama Be the Female Elvis?

8 CAN A FUJIYAMA MAMA BE THE FEMALE ELVIS? The wild, wild women of rockabilly David Sanjek I don't want a headstone for my grave. I want a fucking monument! (Jerry Lee Lewis) 1 You see, I was always a well-endowed girl, and the guys used to tell me that they didn't know how to fit a 42 into a 331!3. (Sun Records artist Barbara Pittman ) 2 Female artists just don't really sell. (Capital Records producer Ken Nelson) 3 In the opening scene of the 199 3 film True Romance (directed by Tony Scott from a script by Quentin Tarantino), Clarence Worly (Christian Slater) perches on a stool in an anonymous, rundown bar. Addressing his com ments to no one in particular, he soliloquises about 'the King'. Simply put, he asserts, in Jailhouse Rock (19 5 7), Elvis embodied everything that rocka billy is about. 'I mean', he states, 'he is rockabilly. Mean, surly, nasty, rude. In that movie he couldn't give a fuck about nothin' except rockin' and rollin' and livin' fast and dyin' young and leavin' a good lookin' corpse, you know.' As he continues, Clarence's admiration for Elvis transcends mere identification with the performer's public image. He adds, 'Man, Elvis looked good. Yeah, I ain't no fag, but Elvis, he was prettier than most women, most women.' He now acknowledges the presence on the barstool next to him of a blank-faced, blonde young woman. Unconcerned that his overheard thoughts might have disturbed her, he continues, 'I always said if I had to fuck a guy - had to if my life depended on it - I'd 137 DAVID SANJEK THE WILD,~ WOMEN OF ROCK~BILLY fuck Elvis.' The woman concurs with his desire to copulate with 'the and Roll; rockabilly, he writes, 'suggested a young white man celebrating King', but adds, 'Well, when he was alive, not now.' freedom, ready to do anything, go anywhere, pausing long enough for In the heyday of rockabilly, one imagines more than a few young men apologies and recriminations, but then hustling on towards the new'. -

“Outlaw Pete”: Bruce Springsteen and the Dream-Work of Cosmic American Music

“Outlaw Pete”: Bruce Springsteen and the Dream-Work of Cosmic American Music Peter J. Fields Midwestern State University Abstract During the 2006 Seeger Sessions tour, Springsteen shared his deep identification with the internal struggle implied by old spirituals like “Jacob’s Ladder.” While the Magic album seemed to veer wide of the Seeger Sessions ethos, Working on a Dream re-engages mythically with what Greil Marcus would call “old, weird America” and Gram Parsons deemed “cosmic American music.” Working suggests the universe operates according to “cosmic” principles of justice, judgment, and salvation, but is best understood from the standpoint of what Freud would call “dream work” and “dream thoughts.” As unfolded in Frank Caruso’s illustrations for the picturebook alter ego of Working‘s “Outlaw Pete,” these dynamics may allude to Springsteen’s conflicted relationship with his father. The occasion of the publication in December 2014 of a picturebook version of Bruce Springsteen’s “Outlaw Pete,” the first and longest song on the album Working on a Dream (2009), offers Springsteen scholars and fans alike a good reason to revisit material that, as biographer Peter Ames Carlin remarks, failed in the spring American tour of that year to “light up the arenas.”1 When the Working on a Dream tour opened in April 2009 in San Jose, at least Copyright © Peter Fields, 2016. I want to express my deep gratitude to Irwin Streight who read the 50 page version of this essay over a year ago. He has seen every new draft and provided close readings and valuable feedback. I also want to thank Roxanne Harde and Jonathan Cohen for their steady patience with this project, as well as two reviewers for their comments.