The Politics of Authenticity in Rock and Electronic Dance Music By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Dancing Under Socialism: Ex-Yu Electronica | Norient.Com 25 Sep 2021 22:47:34

Dancing Under Socialism: Ex-Yu Electronica | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 22:47:34 Dancing Under Socialism: Ex- Yu Electronica by Gregor Bulc In the last couple of years, various collections of electronic music from former Yugoslavia popped up, ranging from numerous downloadable CDR mixtapes to official compilation albums. The Croatian film critic and media connoisseur Željko Luketić presents his favorite songs and clips. The trend of officially published compilations of Yugoslav electronic music started arguably in 2010 when Subkulturni Azil from Maribor, Slovenia, released the Ex Yu Electronica Vol I: Hometaping in Self-Management vinyl on its Monofonika label, followed by the Vol II: Industrial Electro Bypasses in the North – In Memoriam Mario Marzidovšek, dedicated solely to Slovenian scene. Here are some of the artist featured on these two vinyls, whose creativity and innovation, as well as sheer volume of music production and distribution effort remain unmatched to this day. Electric Fish – Stvar V (Slovenia 1985) Andrei Grammatik – Poslanica Duholovcima (Macedonia/Serbia 1988) https://norient.com/blog/ex-yu-electronic-music Page 1 of 6 Dancing Under Socialism: Ex-Yu Electronica | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 22:47:34 Mario Marzidovšek aka Merzdow Shek – Suicide In America (Slovenia 1987) The Ex Yu Electronica Vol III contains the art duo Imitacija Života’s hard-to- come-across videos, followed by a rarefied industrial electro breakbeat cover of Bob Dylan’s classic from Jozo Oko Gospe: Imitacija Života – Instrumentator (Croatia 1989) Video -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

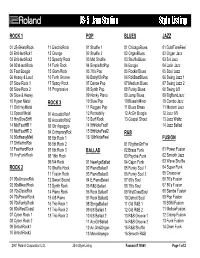

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Steve Cropper | Primary Wave Music

STEVE CROPPER facebook.com/stevecropper twitter.com/officialcropper Image not found or type unknown youtube.com/channel/UCQk6gXkhbUNnhgXHaARGskg playitsteve.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Cropper open.spotify.com/artist/1gLCO8HDtmhp1eWmGcPl8S If Yankee Stadium is “the house that Babe Ruth built,” Stax Records is “the house that Booker T, and the MG’s built.” Integral to that potent combination is MG rhythm guitarist extraordinaire Steve Cropper. As a guitarist, A & R man, engineer, producer, songwriting partner of Otis Redding, Eddie Floyd and a dozen others and founding member of both Booker T. and the MG’s and The Mar-Keys, Cropper was literally involved in virtually every record issued by Stax from the fall of 1961 through year end 1970.Such credits assure Cropper of an honored place in the soul music hall of fame. As co-writer of (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay, Knock On Wood and In The Midnight Hour, Cropper is in line for immortality. Born on October 21, 1941 on a farm near Dora, Missouri, Steve Cropper moved with his family to Memphis at the age of nine. In Missouri he had been exposed to a wealth of country music and little else. In his adopted home, his thirsty ears amply drank of the fountain of Gospel, R & B and nascent Rock and Roll that thundered over the airwaves of both black and white Memphis radio. Bit by the music bug, Cropper acquired his first mail order guitar at the age of 14. Personal guitar heroes included Tal Farlow, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Chet Atkins, Lowman Pauling of the Five Royales and Billy Butler of the Bill Doggett band. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy Martin J. Zeilinger York University, Canada [email protected] Abstract This essay considers how chipmusic, a fairly recent form of alternative electronic music, deals with the impact of contemporary intellectual property regimes on creative practices. I survey chipmusicians’ reusing of technology and content invoking the era of 8-bit video games, and highlight points of contention between critical perspectives embodied in this art form and intellectual property policy. Exploring current chipmusic dissemination strategies, I contrast the art form’s links to appropriation-based creative techniques and the ‘demoscene’ amateur hacking culture of the 1980s with the chiptune community’s currently prevailing reliance on Creative Commons licenses for regulating access. Questioning whether consideration of this alternative licensing scheme can adequately describe shared cultural norms and values that motivate chiptune practices, I conclude by offering the concept of a moral economy of appropriation-based creative techniques as a new framework for understanding digital creative practices that resist conventional intellectual property policy both in form and in content. Keywords: Chipmusic, Creative Commons, Moral Economy, Intellectual Property, Demoscene Introduction The chipmusic community, like many other born-digital creative communities, has a rich tradition of embracing and encouraged open access, collaboration, and sharing. It does not like to operate according to the logic of informational capital and the restrictive enclosure movements this logic engenders. The creation of chipmusic, a form of electronic music based on the repurposing of outdated sound chip technology found in video gaming devices and old home computers, centrally involves the reworking of proprietary cultural materials. -

Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa

All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 PhD Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD in Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London 2013 Cover Image: Party Goer Dancing at House Party Brixton, Johannesburg, 2005 (Author’s own) 1 Acknowledgements I owe a massive debt to a number of people and institutions who have made it possible for me to give the time I have to this work, and who have supported and encouraged me throughout. The research and writing of this project was made financially possible through a generous studentship from the ESRC. I also benefitted from the receipt of a completion grant from the Goldsmiths Anthropology Department. Sophie Day took over my supervision at a difficult point, and has patiently assisted me to see the project through to submission. John Hutnyk’s and Sari Wastel’s early supervision guided the incubation of the project. Frances Pine and David Graeber facilitated an inspiring and supportive writing up group to formulate and test ideas. Keith Hart’s reading of earlier sections always provided critical and pragmatic feedback that drove the work forward. Julian Henriques and Isaak Niehaus’s helpful comments during the first Viva made it possible for this version to take shape. Hugh Macnicol and Ali Clark ensured a smooth administrative journey, if the academic one was a little bumpy. Maia Marie read and commented on drafts in the welcoming space of our writing circle, keeping my creative fires burning during dark times. -

![Kanye West's Sonic [Hip Hop] Cosmopolitanism](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5103/kanye-wests-sonic-hip-hop-cosmopolitanism-205103.webp)

Kanye West's Sonic [Hip Hop] Cosmopolitanism

÷ Chapter 7 Kanye West's Sonic [Hip Hop] Cosmopolitanism Regina N. Bradley On September 2, 2005, Kanye West appeared on an NBC benefit telecast for Hurricane Katrina victims. West, emotionally charged and going off script, blurted out, "George Bush doesn't care about black people." Early ill his rapping career and fi'esh off the critically acclaimed sophomore album Late Registration, West thrusts himself into the public eye--debatably either on accident or purposefully--as a ÷ scemingly budding cuhural-political pundit. For the audience, West's ÷ growing popularity and visibility as a rapper automatically translated his concerns into a statement on behalf of all African Americans. West, however, quickly shies away from being labeled a leader, disclaiming his outburst as a personal opinion. In retrospect, West states: "When I made my statement about Katrina, it was a social statement, an emo- tional statement, not a political one" (Scaggs, 2007). Nevertheless, his initial comments about the Bush administration's handling of Katrina positioned him both as a producer of black cultural expres- sion and as a mediator of said blackness. It is from this interstitial space that West continued to operate moving fbrward, using music-- and the occasional outburstÿto identify himself as transcending the expectations placed upon his blackness and masculinity. West utilizes music to tread the line between hip-hop ktentity poli- tics and his own convictions, blurring discourses through which race and gender are presented to a (inter)national audience, it is important to note that hip-hop serves doubly as an intervention of American capitalism and of black agency. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music with Ellen Allien

Editorial A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music With Ellen Allien Kian McHugh | August 3, 2020 When my Zoom call with Ellen Allien connects, at last, I feel weeks of anticipation turn to uncontrollable excitement. My fingers, sweaty from nerves, and a poorly brewed Starbucks coffee, type out the instructions on how to get her audio configured. Ellen is lounging in her Ibiza flat where she has painted all of the walls completely black so that when the sun shines through her window, the room glows yellow. The first fully formed thought I could pencil down was that her posture seemed to denote a sincere attention to detail and confidence in comfort that most others lack. For the first 2 minutes of the call, we both instinctively laugh, muted, and unaware that our discussion of Techno would soon gravitate toward, and then find unexpected momentum in… a deep consideration of Techno, God, and religion. “Rap is where you rst heard it… If rap is more an American phenomenon, techno is where it all comes together in Europe as producers and musicians engage in a dialogue of dazzling speed.” – Jon Savage (English writer, broadcaster and music journalist). In Hanif Abdurraqib’s 2019 book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, he so beautifully praises “the low end” of a track: “The feeling of something familiar that sits so deep in your chest that you have to hum it out … where the bass and the kick drums exist.” His point rings true across all music that is heavily percussion driven. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism.