“You've Been with the Professors”: Influence, Appropriation, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tell-Tale Signs - Edgar Allan Poe and Bob Dylan: Towards a Model of Intertextuality

ATLANTIS. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies. 31.2 (December 2009): 41–56 ISSN 0210-6124 Tell-Tale Signs - Edgar Allan Poe and Bob Dylan: Towards a Model of Intertextuality Christopher Rollason Metz, France [email protected] This article shows how the poetry and prose of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) cast a long shadow over the work of America’s greatest living songwriter, Bob Dylan (1941-). The work of both artists straddles the dividing-line between ‘high’ and ‘mass’ culture by pertaining to both: read through Poe, Dylan’s work may be seen as a significant manifestation of American Gothic. It is further suggested, in the context of nineteenth- century and contemporary debates on alleged ‘plagiarism’, that the textual strategy of ‘embedded’ quotation, as employed by both Poe and Dylan, points up the need today for an open and inclusive model of intertextuality. Keywords: culture; Dylan; Gothic; intertextuality; Poe; quotation Tell-tale signs - Edgar Allan Poe y Bob Dylan: hacia un modelo de intertextualidad Este artículo explica cómo la poesía y la prosa de Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) proyectan una larga sombra sobre la obra del mayor cantautor vivo de Estados Unidos, Bob Dylan (1941-). Ambos artistas se ubican en una encrucijada entre la cultura ‘de elite’ y la ‘de masas’, puesto que la obra de cada uno se sitúa en ambos dominios a la vez: leída a través de Poe, la obra dylaniana aparece como una importante manifestación del gótico norteamericano. Se plantea igualmente la hipótesis de que, en el marco de los debates, tanto decimonónicos como contemporáneos, sobre el supuesto ‘plagio’, la estrategia textual, empleada tanto por Poe como por Dylan, de la cita ‘encajada’ señala la necesidad urgente de plantear un modelo abierto y global de la intertextualidad. -

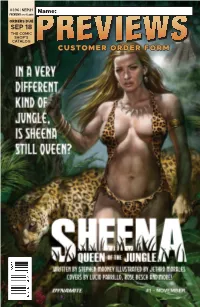

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

Settin' My Dial on the Radio

SETTIN ’ MY DIAL ON THE RADIO BOB DYLAN 2006 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , NEW RELEASES , RECORDINGS & BOOKS . © 2010 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Settin’ My Dial On The Radio — Bob Dylan 2006 page 2 of 86 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................4 2 2006 AT A GLANCE ..............................................................................................................................................................4 3 THE 2006 CALENDAR ..........................................................................................................................................................4 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ..............................................................................................................................6 4.1 MODERN TIMES ................................................................................................................................................................6 4.2 BLUES ..............................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3 THEME TIME RADIO HOUR : BASEBALL ............................................................................................................................8 -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Matrices of 'Love and Theft': Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan

Twentieth-Century Music 18/2, 249–279 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572221000013 Matrices of ‘Love and Theft’: Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan MIMI HADDON Abstract This article uses Joan Baez’s impersonations of Bob Dylan from the mid-1960s to the beginning of the twenty-first century as performances where multiple fields of complementary discourse con- verge. The article is organized in three parts. The first part addresses the musical details of Baez’s acts of mimicry and their uncanny ability to summon Dylan’s predecessors. The second con- siders mimicry in the context of identity, specifically race and asymmetrical power relations in the history of American popular music. The third and final section analyses her imitations in the context of gender and reproductive labour, focusing on the way various media have shaped her persona and her relationship to Dylan. The article engages critical theoretical work informed by psychoanalysis, post-colonial theory, and Marxist feminism. Introduction: ‘Two grand, Johnny’ Women are forced to work for capital through the individuals they ‘love’. Women’s love is in the end the confirmation of both men’s and their own negation as individ- uals. Nowadays, the only possible way of reproducing oneself or others, as individuals and not as commodities, is to dam this stream of capitalist ‘love’–a ‘love’ which masks the macabre face of exploitation – and transform relationships between men and women, destroying men’s mediatory role as the representatives of state and capital in relation to women.1 I want to start this article with two different scenes from two separate Bob Dylan films. -

Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 Page 1

AIN 'T GOIN ' NOWHERE BOB DYLAN 1967 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , RELEASES , TAPES & BOOKS . © 2001 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 page 1 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 2 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE ................................................................................................... 2 3 CALENDAR .............................................................................................................................. 2 4 RECORDINGS ......................................................................................................................... 3 5 JOHN WESLEY HARDING ................................................................................................... 3 6 SONGS 1967 .............................................................................................................................. 5 7 SOURCES .................................................................................................................................. 6 8 SUGGESTED READINGS ...................................................................................................... 7 8.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

The Bob Cats Newsletter 2020-07-10

THE BOB CATS NEWSLETTER JULY 10, 2020. CELEBRATING THE ART AND THE MANY LIVES OF BOB DYLAN • NOBEL PRIZE LAUREATE SONG & DANCE MAN. INSPIRED BY THEME TIME RADIO HOUR AND THE SPIRIT IN WHICH IT WAS MADE. ESTABLISHED 2006 BY PETER HOLST • 13 YEARS AND RUNNING. HTTPS://THEBOBCATSNEWSLETTER.WORDPRESS.COM Welcome to another edition of the Bob Cats Newsletter. It's night time in the big city. The heavy bass line from an electric Fender bass guitar rattles the walls of the humble abode of the cracked actor on his hands and knees looking for the bottle cap to his Mexican root beer. A streetcar named Macondo goes by adding tremble and wobble to the painted boards on top of The Black Swan. He recognizes the fateful steps of madam McIntyre-Mire, landlord and loan shark from the Baltic Midlands, bringing wine and bread on a silver tray for his nocturnal shift. She’s wearing a quarantine mask in leather and doesn’t bother to knock. Nothing in this living world would upset her except late rents and polkas. The night nurse’s crying in her coffee in an all-night café. Life is but a string well-tuned or cut. The sign of the Saint James Hotel’s twinkles, it’s a bad wire and a burned connection. The night manager tears off his toupee and screams at the slow and tardy ceiling fan in mahogany carrying yesteryear’s dust and July flies to of a waltz by Strauss on the radio. ••• ROUGH AND ROWDY WAYS • THE REVIEWS BOB DYLAN - ROUGH AND ROWDY WAYS. -

November '92 Sound

mb Nove er ’92 . 2 , NoSS UUNN DD HHHH, YOU DON’T know the shape I’m “O in,” Levon Helm was wailing plaintively over the P.A. as the lights came up at Off Broad- way, a St. Louis nightclub. The DJ’s choice of that particular Band normally prohibits). Brian McTavish of the number couldn’t have been more Star’s “Nighthawk” column was on assign- relevant. Four days on the road ment, so no luck there. A television spot with the Tom Russell Band were wasn't in the budget, so we'd have to rely coming to a close, leaving me primarily on word of mouth for ticket sales. fatigued and exhilarated at the same time. Day 1 – Kansas City The show had run late, and The Tom Russell Band, standin’ on the corner: Barry the management was doing its Ramus (bass), Fats Kaplin (accordion, pedal steel, Waiting at the Comfort Inn for the band harmonica, and more), Tom Russell (guitar, vocals), to roll in to town provided a chance to see a best to herd patrons out the Mike Warner (drums, backing vocals), Andrew Hardin door. As the crowd congratulat- (guitar, harmony vocals). prima donna in action. A member of Lash ing the band dispersed, S LaRue’sband was pressuring the desk clerk staff cartoonist Dug joined me in ap- to change his room assignment, first to down the hall, then, deciding that wasn’t proaching Tom, and in our best Wayne and up a request for an interview left on his toll good enough, to a different floor. -

Bob Dylan Musician, Keith Negus. This File Contains the Pre-Proof

Bob Dylan Musician, Keith Negus. This file contains the pre-proof versions of Chapter One and Chapter Five from Bob Dylan, presented here in this format with the permission of Equinox Publishing. I have called this text Bob Dylan Musician because this was the original agreed title of the book right up to the moment just before publication when pressure from the US publisher resulted in the term ‘musician’ being reluctantly (from my perspective) expunged from the title. That word – musician – was there to concisely signal how my approach differs from most other books on Bob Dylan. I am interested in his work and practice as a musician, rather than his lyrics as poetry or the relationship between his biography and musical art. The book contains five chapters, so these two chapters introduce and conclude the study. If anyone would like electronic copies of additional chapters I am happy to provide these, as long as they are used only for research and teaching. Keith Negus June 2013 CHAPTER ONE Surroundings On 31 October 1964 Bob Dylan performed at the Philharmonic Hall in New York City, just two years after signing a recording contract and with four albums already released. Having quickly gained recognition as a folk ‘protest singer’ he was rapidly moving away from songs of social commentary and ‘finger pointing’. Dylan was beginning to use the popular song in a new and radical manner to explore more internal or subjective experiences, whilst experimenting with the sound, meaning and rhythm of words. Within three months, when recording his fifth album, no longer performing alone with acoustic guitar and harmonica, he was beginning to create an abrasive yet ethereal sonority, mixing the acoustic and electric textures of folk, electric blues, rock’n’roll, gospel, country and pop.