Chapter One “The Woody Guthrie Jukebox” Bob Dylan and Early Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

Bob Dylan's Life

Bob Dylan's Life Robert Allen Zimmerman born May 24 1941 in Duluth, Minnesota known by the pseudonym of Bob Dylan, was an American singer, song-writer, musician and author. He is an influential figure in popular music and culture. He became a reluctant « voice of a generation » when he moved to New York in the 1961 where he wrote songs like « Blowin' in the Wind » and « The Times Are a-Changin’ ». Those songs were to become anthems for Civil Rights Movement and anti-war movement. His recording career goes on for more than fifty years and he explored many musical genres from folk, blues, country to gospel, rock and roll … He recorded 38 studio albums, starting with Bob Dylan (1968) and still records songs today. Dylan's lyrics contain political, social, philosophical and literary influences and over the years he defied pop music conventions. Dylan performs with guitar, keyboards and harmonica. He published his album on Columbia Records and Asylum Records. Since 1994, he also published seven books of drawings and paintings. As a musician, he sold more than 100 million records, making him one of the best-selling artists of all time. He received many awards including eleven Grammy Awards, a Golden Globe Award, an Academy Award and many other prizes such as an NME Award. Nowadays Dylan still receives huge recognition: in 2012 the President Barack Obama gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 2016 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature « for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition ». -

Conor Mcpherson's Girl from the North Country

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship English Winter 2018 The aM rriage of Heaven and Hell: Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country Graley Herren Xavier University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Herren, Graley, "The aM rriage of Heaven and Hell: Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country" (2018). Faculty Scholarship. 584. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty/584 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graley Herren • The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Death and Rebirth in Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country In February 2015, the Irish American playwright John Patrick Shanley con- ducted a revealing interview with his Dublin counterpart Conor McPherson for American Theatre magazine. Asked about his preoccupation with the supernat- ural, McPherson intimated, “I remember when I was a little kid, I was always interested in ghosts and scary things. If I want to rationalize it, it’s probably a search for God.” This quest led him to theater. “There’s something so religious about the theatre,” he stated. We’re all sitting there in the dark, and there’s some- thing about how the stage glows in the darkness, which is such a beautiful pic- ture of human existence. What’s really interesting is the darkness that surrounds the picture. -

Tell-Tale Signs - Edgar Allan Poe and Bob Dylan: Towards a Model of Intertextuality

ATLANTIS. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies. 31.2 (December 2009): 41–56 ISSN 0210-6124 Tell-Tale Signs - Edgar Allan Poe and Bob Dylan: Towards a Model of Intertextuality Christopher Rollason Metz, France [email protected] This article shows how the poetry and prose of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) cast a long shadow over the work of America’s greatest living songwriter, Bob Dylan (1941-). The work of both artists straddles the dividing-line between ‘high’ and ‘mass’ culture by pertaining to both: read through Poe, Dylan’s work may be seen as a significant manifestation of American Gothic. It is further suggested, in the context of nineteenth- century and contemporary debates on alleged ‘plagiarism’, that the textual strategy of ‘embedded’ quotation, as employed by both Poe and Dylan, points up the need today for an open and inclusive model of intertextuality. Keywords: culture; Dylan; Gothic; intertextuality; Poe; quotation Tell-tale signs - Edgar Allan Poe y Bob Dylan: hacia un modelo de intertextualidad Este artículo explica cómo la poesía y la prosa de Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) proyectan una larga sombra sobre la obra del mayor cantautor vivo de Estados Unidos, Bob Dylan (1941-). Ambos artistas se ubican en una encrucijada entre la cultura ‘de elite’ y la ‘de masas’, puesto que la obra de cada uno se sitúa en ambos dominios a la vez: leída a través de Poe, la obra dylaniana aparece como una importante manifestación del gótico norteamericano. Se plantea igualmente la hipótesis de que, en el marco de los debates, tanto decimonónicos como contemporáneos, sobre el supuesto ‘plagio’, la estrategia textual, empleada tanto por Poe como por Dylan, de la cita ‘encajada’ señala la necesidad urgente de plantear un modelo abierto y global de la intertextualidad. -

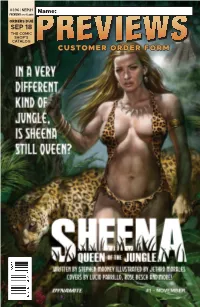

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

![Mirror Image [Pdf Format]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0919/mirror-image-pdf-format-310919.webp)

Mirror Image [Pdf Format]

Rob Halliday Waxes Lyrical on Madame Tussaud’s, New York revamped the London show while at the same time moving into other areas of Mirror entertainment. It now owns Alton Towers, Thorpe Park, Chessington World of Adventures and a themed attraction at Warwick Castle, and manages the London Eye. The first surprise: discovering Most recently, new exhibitions have opened in that the building on the Image Las Vegas and Hong Kong. Marylebone Road in London, familiar from childhood On November 15th, these were joined by trips, is actually part of a multi-million learnt wax-modelling from her mother’s Tussaud’s New York. The new, 85,000sq.ft pound entertainment empire that now employer, Philippe Curtius, she later found museum is located on 42nd Street, west of spans the globe. herself imprisoned with the future Empress Broadway, right at the heart of Mayor Josephine in 1793, a contact that allowed her Giuliani’s plan to revitalise Times Square and, The second surprise: discovering that the to model Napoleon after the revolution. from there, the city as a whole. This block is waxwork figures of the great, the good and Tussaud inherited Curtius’ wax exhibition in effectively one massive construction site, mere celebrities, vaguely remembered from 1794; she took her show on tour in the UK in cinemas and shops all at various stage of those same childhood trips and gently derided 1802, and established a permanent base in completion. Tussaud’s light, airy foyer offers in the years since, are not only brilliantly Baker Street in 1835. Tussaud herself died in immediate respite from the chaos outside, executed works of art, but are also completely 1850, but her grandsons moved the show to its with Whoopi Goldberg present to greet fascinating to be around. -

On the Road with Janis Joplin Online

6Wgt8 (Download) On the Road with Janis Joplin Online [6Wgt8.ebook] On the Road with Janis Joplin Pdf Free John Byrne Cooke *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893672 in Books John Byrne Cooke 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .93 x 5.43l, 1.00 #File Name: 0425274128448 pagesOn the Road with Janis Joplin | File size: 33.Mb John Byrne Cooke : On the Road with Janis Joplin before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised On the Road with Janis Joplin: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A Must Read!!By marieatwellI have read all but maybe 2 books on the late Janis Joplin..by far this is one of the Best I have read..it showed the "music" side of Janis,along with the "personal" side..great book..Highly Recommended,when you finish this book you feel like you've lost a band mate..and a friend..she could have accomplished so much in the studio,such as producing her own records etc..This book is excellent..0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.By Mic DAs a teen in 1969 and growing up listening to Janis and all the bands of the 60's and 70's, this book was very enjoyable to read.If you ever wondered what it might be like to be a road manager for Janis Joplin, John Byrne Cooke answers it all.Those were extra special days for all of us and John's descriptions of his experiences, helps to bring back our memories.Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

Snow Over Interstate 80, Un Immaginario Album Di Canzoni Natalizie Registrato Da Bob Dylan a Metà Degli Anni '60

Nel 1975 il New Musical Express pubblicò, per ridere coi propri lettori, la finta recensione di Snow Over Interstate 80, un immaginario album di canzoni natalizie registrato da Bob Dylan a metà degli anni '60. Snow Over Interstate 80 Picture of the spoof 1975 The eventual 2009 'Twas The Night Before album cover from Wim album cover Christmas - 7" single B- van der Mark side [Home] [ Up ] The following spoof article appeared in the UK music magazine "New Musical Express" in 1975. I've included it here not only because it's pretty funny but also because the original list of unreleased Dylan songs that started this project off included three "mystery" names: FREEWHEELIN', NIGHTINGALE'S CODE and WOODSTOCK YULE. Somewhere along the line the fact that these were spoof titles had been lost, so I wanted to set the record straight. Remember, the article below is a hoax! Bob of course released a genuine Christmas album, Christmas In The Heart, in 2009. Alan Fraser DYLAN - the missing Christmas album At last, definite evidence has come to light that confirms that, in the autumn of 1965, Bob Dylan did record a Christmas Album. The existence of the Dylan Christmas Album has always been hotly denied by Dylan himself, his management, and his record company. Even the most determined bootleggers and Dylanologists have been unable to obtain extant copies of the record, the master tapes of which were allegedly destroyed when the project was suddenly nixed by Dylan himself at the eleventh hour. Now, "Thrills" has obtained a copy, rumoured to be one of only seven copies in the world, the other copies being in the possession of Dylan himself, his then manager Albert Grossman, ex-CBS president Clive Davis and an anonymous French collector said to have paid $100,000 for it in 1966. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ...............................................................................................................................