Issue #6, September 24, 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Javni Poziv Fmroi 2019 – Konačna Rang Lista Potencijalnih Korisnika Za Rekonstrukciju Stambenih Objekata – Grad Bijeljina

JAVNI POZIV FMROI 2019 – KONAČNA RANG LISTA POTENCIJALNIH KORISNIKA ZA REKONSTRUKCIJU STAMBENIH OBJEKATA – GRAD BIJELJINA Red.br. Ime i prezime Adresa sanacije/Sadašnja adresa Broj bodova 1. Kasić (Mujo) Avdulaziz Braće Lazić 227, Bijeljina 220 Braće Lazić 227, Bijeljina 2. Alijević (Ruždija) Šefik Nikole Tesle 23, Bijeljina 210 1. maj 31, Janja 3. Bilalić (Mehmed) Vahidin Drinska 107, Janja 210 Drinska 107, Janja 4. Halilović Admir Mehmed N.Tesle bb Bijeljina 200 Mula Alije Sadikovića 21 Bijeljina 5. Krivić (Ramo) Enes Dž. Bijedića 15, Bijeljina 200 Dž. Bijedića 15, Bijeljina 6. Krilašević (Osman) Mevludin I.L. Ribara 15, Bijeljina 200 Bobarovača 15, Bijeljina 7. Osmanović (Zinija) Adi Jurija Gagarina 39, Bijeljina 200 Jurija Gagarina 39, Bijeljina 8. Sivčević (Ohran) Osman Đorđa Vasića 41, Janja 200 Brzava 77, Janja 9. Spahić (Nedžib) Mensur Braće Lazić 203, Bijeljina 190 Braće Lazić 203, Bijeljina 10. Alibegović (Ibrahim) Sakib M.M. Dizdara 63, Bijeljina 190 M.M. Dizdara 63, Bijeljina 11. Pobrklić (Jusuf) Mensur Braće Lazić bb, Janja 180 Dž. Bijedića 36, Janja 12. Hrustić (Omer) Sead 24. Septembar 14, Bijeljina 180 24. Septembar 14, Bijeljina 13. Godušić (Ragib) Nešat M.M. Dizdara 19A, Bijeljina 180 M.M. Dizdara 19A, Bijeljina 14. Demirović (Emin) Mustafa Desanke Maksimović 46, Bijeljina 180 Desanke Maksimović 46, Bijeljina 15. Karjašević (Huso) Ahmed Mlade Bosne 5, Bijeljina 180 Mlade Bosne 5, Bijeljina 16. Tuzlaković (Muhamed) Emir Miloša Obilića 104, Bijeljina 180 Miloša Obilića 106, Bijeljina 17. Bajrić (Alija) Mujo D. Tucovića 32, Bijeljina 180 D. Tucovića 32, Bijeljina 18. Osmanagić (Mustafa) Omer Brzava 119, Bijeljina 170 Brzava 119, Bijeljina 19. -

Zakon O Nacionalnom Parku „Drina“

ZAKON O NACIONALNOM PARKU „DRINA“ Član 1. Ovim zakonom uređuju se granice, zone i režimi zaštite, pitanja upravljanja, zaštite i razvoja Nacionalnog parka „Drina“ (u daljem tekstu: Nacionalni park). Član 2. Nacionalni park je područje izuzetnih prirodnih vrijednosti, koje čini klisurasto- kanjonska dolina rijeke Drine kao jedna od najznačajnijih riječnih dolina Republike Srpske, sa brojnim staništima endemičnih i reliktnih biljnih vrsta, te izuzetnim diverzitetom flore i faune, koje je namijenjeno očuvanju postojećih prirodnih vrijednosti i resursa, ukupne pejzažne, geološke i biološke raznovrsnosti, kao i zadovoljenju naučnih, obrazovnih, duhovnih, estetskih, kulturnih, turističkih, zdravstveno-rekreativnih potreba i ostalih aktivnosti u skladu sa načelima zaštite prirode i održivog razvoja. Član 3. Na pitanja od značaja za zaštitu, razvoj, unapređivanje, upravljanje, finansiranje, kaznene odredbe i održivo korišćenje Nacionalnog parka koja nisu uređena ovim zakonom primjenjuju se posebni propisi kojim se uređuju pitanja nacionalnih parkova, zaštite prirode i drugi zakoni i podzakonski akti kojima se reguliše ova oblast. Član 4. (1) Nacionalni park prostire se na području opštine Srebrenica u ukupnoj površini od 6.315,32 hektara. (2) Opis spoljne granice Nacionalnog parka: Početna tačka opisa granice obuhvata Nacionalnog parka je u tromeđi opština Srebrenica, Višegrad i Rogatica (tačka A). Granica ide ka sjeveroistoku do tromeđe opština Srebrenica, Višegrad i Bajine Bašte u Srbiji (tačka B). Od tačke A do tačke B, granica ide jezerom Perućac, odnosno granicom između opština Srebrenica i Višegrad. Od tromeđe opština Srebrenica, Višegrad i Bajine Bašte u Srbiji (tačka B), granica ide do krune brane Perućac (tačka V). Od tačke B do tačke V, granica ide jezerom Perućac, odnosno granicom između Bosne i Hercegovine i Srbije. -

Skupština Opštine Srebrenica Odluke, Zaključci, Programi I Javni Konkursi

BILTEN SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA BROJ: 1/2015 Srebrenica, Januar 2015. god. SKUPŠTINA OPŠTINE SREBRENICA ODLUKE, ZAKLJUČCI, PROGRAMI I JAVNI KONKURSI Broj:01-022-185 /14 ODLUKE SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA Srebrenica, 26.12.2014. god. Broj:01-022-184/14 Na osnovu člana 31. Zakona o budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske Srebrenica, 26.12.2014. god. ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 121/12 ), a u skladu sa Zakonom o trezoru ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 16/05 i Na osnovu člana 5. Zakona o Budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske 92/09) i člana 30. Zakona o lokalnoj samoupravi ("Službeni glasnik ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 121/12), člana 30. Zakona Republike Srpske", broj: 101/04, 42/05, 118/05 i 98/13) i člana 32. Statuta Opštine Srebrenica ("Bilten opštine Srebrenica", broj: 10/05), o lokalnoj samoupravi ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: Skupština opštine Srebrenica na XVII redovnoj sjednici održanoj 101/04, 42/05,118/05 i 98/13) i člana 32. Statuta Opštine Srebrenica 26.12.2014. godine je usvojila: ("Bilten opštine Srebrenica", broj: 10/05), Skupština opštine Srebrenica na XVII redovnoj sjednici održanoj 26.12.2014. godine je Odluku usvojila: o izvršenju Budžeta opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu Odluku Član 1. o usvajanju Budžeta opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu Ovom Odlukom propisuje se način izvršenja Budžeta Opštine Član 1. Srebrenica za 2015. godinu (u daljem tekstu: budžet). Budžet opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu sastoji se od: Ova Odluka će se sprovoditi u saglasnosti sa Zakonom o budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske i Zakonom o trezoru. 1. Ukupni prihodi i primici: 6.883.00000 KM, od toga: a) Redovni prihodi tekućeg perioda: 6.115.500,00 KM; Sve Odluke, zaključci i rješenja koji se odnose na budžet moraju biti u b) Tekući grantovi i donacije: 767.500,00 KM. -

ODLUKE SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA Član 4

SLUŽBENI GLASNIK OPŠTINE SREBRENICA BROJ: 2/2019 Srebrenica, 15.10.2019. god. SKUPŠTINA OPŠTINE SREBRENICA ODLUKE, ZAKLJUČCI, PROGRAMI I JAVNI KONKURSI AKTI NAČELNIKA OPŠTINE SREBRENICA ODLUKE SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA Član 4. Broj: 01-022-122/19 Ova odluka ne predstavlja osnov za promjenu Srebrenica, 02.04.2019. god. imovinsko pravnih odnosa u pogledu predmetnih prostorija koje se daju na korištenje, ašto će biti U skladu sa članom 39. Zakona o lokalnoj samoupravi definisano i samim ugovorom. ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 97/16), člana 34. Statuta opštine Srebrenica ("Službeni glasnik opštine Srebrenica", broj: 2/18), a na prijedlog Član 5. Načelnika opštine, Skupština opštine Srebrenica na XVII redovnoj sjednici održanoj dana 24.04.2019. Ova Odluka stupa na snagu danom donošenja i ista će godine donosi: se objaviti u "Službenom glasniku opštine Srebrenica". ODLUKU Obrazloženje o davanju kancelarijskog prostora 38m² - II sprat ranije robne kuće u "Srebreničanka" na korištenje Skupština opštine Srebrenica dodjeljuje predmetnu MDD "Merhamet" Srebrenica prostoriju MDD "Merhamet" Srebrenica na korištenje da bi se obezbjedio nesmetan i funkcionalan rad Član 1. Društva. Ovom odlukom daje se na korištenje poslovna DOSTAVLJENO: prostorija (38 m²) smještena na II spratu nekadašnje 1. Načelniku opštine; robne kuće Srebreničanka (Trg Mihajla Bjelakovića bb) 2. Stručnoj službi SO; Muslimanskom dobortvornom društvu "Merhamet" 3. MDD "Merhamet" Srebrenica; Srebrenica. 4. a/a. Član 2. PREDSJEDNIK SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE Nedib Smajić, s.r. MDD "Merhamet" Srebrenica će navedeni prostor koristiti bez nadoknade na vremenski period od 10 godina (sa mogućnostima raskida, odnosno produženja vremenskog trajanja ugovora). Predmetni prostor se nalazi u dosta zapuštenom stanju te MDD "Merhamet" Srebrenica na sebe preuzima obavezu adaptacije istog. -

Strategije Razvoja Opštine Srebrenica Za Period 2018. – 2022.Godine

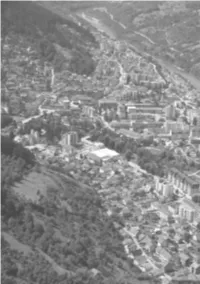

Strategije razvoja opštine Srebrenica za period 2018. – 2022.godine 1. Mladen Grujičić 2. Dušica Kovačević 3. Mela Karić 4. Hasudin Mustafić 5. Bojan Pejić Srebrenica, 2017. godine I -UVOD Slika 1: Geografski položaj opštine Srebrenica Izvor: Odjeljenje za prostorno uređene i stambeno komunalne poslove, Opština Srebrenica 1.1. Geografski položaj i opšti podaci Opština se nalazi na sjeveroistoku Republike Srpske-BiH. Locirana je u središnjem dijelu toka rijeke Drine na koju se prislanja u dužini od 45 km, od čega je oko 23km Perućačko jezero, HE Bajina Bašta. Graniči sa opštinama Bratunac, Milići, Rogatica i Višegrad u BiH, i opštinom Bajina Bašta u Republici Srbiji. Prije rata u okviru regionalno-teritorijalnog uređenja u Republici Bosni i Hercegovini, Srebrenica je pripadala Tuzlanskom okrugu. Tabela 1. Opšti podaci Pokazatelji Opština Srebrenica Površina (km2) 531,96 Gustina naseljenosti (stanovnika/km2) 22 Broj stanovnika (2016.god.) 11698 Broj nezaposlenih (31.03.2017. god.) 1786 Broj zaposlenih (2016. god.) 2000 Prosječna neto plata u 2016.god. (KM) 834 Oranična površina (ha) 11.136 Izvor: Republički zavod za statistiku, Republika Srpska Prostorni plan Republike Srpske (usvojen) 2 1.2. Saobraćajna povezanost Opština se ne nalazi na glavnim regionalnim saobraćajnim koridorima. Pojedini djelovi opštine su bolje povezani sa Republikom Srbijom i sa drugim područjima Bosne i Hercegovine, nego sa urbanim centrom. Do opštine postoje samo putne komunikacije. Prema tome opština Srebrenica spada u saobraćajno slabo povezanu opštinu. Srebrenica je pored regionalnih putnih pravaca (Bratunac-Skelani, Bratunac-Srebrenica-Skelani i Zeleni Jadar-Milići) prije rata imala izrazito razvijenu putno-komunikacionu mrežu makadamskih lokalnih - opštinskih seoskih puteva, koji su se koristili za potrebe stanovništva, turizma, lovnog turizma i privrede. -

Order for Operation Krivaja

''1 l·t Translation 00383593 COMMAND OF ТНЕ DRINA CORPS MILIТARY SECRET Strictly confidential no. 04/156-2 STRICTLУ CONFIOENTIAL Date: 2 July 1995 COPYNo. 3 KRIVAJA-95 ТО ТНЕ COMMANDS OF: the 1st Zpbr /Zvomik infantry brigade/, lst Bpbr /Вirac infantry brigade/, 2nd Rmtbr /Romanija motorised brigade/, lst Brlpbr /Вratunac light infantry brigade/ lst Mlpbr /МiliCi light infantry brigade/, 5th map /mixed artillery regiment/ ORDER FOR ACTNE Ыd /combat activities/ Operation no. 1 Sections /of the topographical map/: 1 : 50,000, Zvomik 3 and 4 and Visegrad 1 and 2 1. - As part of an all out offensive against RepuЫika Srpska territory, the enemy has carried out attacks with а limited objective against the DK /Drina Corps/ units. We believe that in the coming period, the enemy will intensify offensive activities against the DK area of responsiЬility, mainly in the Tuzla-Zvomik and Kladanj Vlasenica directions, with simultaneous activity Ьу the 28th Division forces from the enclaves of Srebrenica and Zepa, in order to cut the DK area of responsiЬility in two, and connect the enclaves with the central part of the territory of former Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is held Ьу the Muslim forces. During the last few days, Muslim forces from the enclaves of Zepa and Srebrenica have been particularly active. Тhеу are infiltrating DTG /sabotage groups/ which are attacking and buming unprotected villages, killing civilians and small isolated units around the enclaves of Zepa and Srebrenica. They are trying especially hard to link up the enclaves and open а corridor to Kladanj. According to availaЫe data, the 28th Division forces are engaged as follows: - The 280th Brigade is Ыocking the Potocari-Srebrenica axis and is in readiness for active operations against Bratunac and the cutting of the Bratunac-Glogova-Konjevic Polje road. -

Paradoxes of Stabilisation: Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Perspective of Central Europe

PARADOXES OF STABILISATION BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF CENTRAL EUROPE Edited by Marta Szpala W ARSAW FEBRUARY 2016 PARADOXES OF STABILISATION BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF CENTRAL EUROPE E dited by Marta Szpala © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Marta Szpala EDITOR Nicholas Furnival CO-OPERATION Anna Łabuszewska, Katarzyna Kazimierska GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOGRAPH ON COVER F. Pallars / Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-62936-78-6 Contents INTRODUCTION /7 PART I. THE INTERNAL CHALLENGES Jan Muś ONE HAND CLAPPING – THE STATE-BUILDING PROCESS AND THE CONSTITUTION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA /17 1. Origins of the Constitution /17 2. Non-territorial division – Constituent Peoples /19 3. Territorial division /19 4. Constitutional consociationalism – institutions, processes, competences and territorial division /21 4.1. Representation of ethnic groups or ethnicisation of institutions /22 4.2. The division of competences /24 4.3. Procedural guarantees of inclusion /26 Conclusions /27 Wojciech Stanisławski THREE NATIONS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA (TO SAY NOTHING OF THE FOURTH). THE QUEST FOR A POST-DAYTON COLLECTIVE BOSNIAN IDENTITY /29 1. The three historical and political nations of Bosnia /31 2. The nations or the projects? /32 3. The stalemate and the protests /34 4. The quest for a shared memory /35 Hana Semanić FRAGMENTATION AND SEGREGATION IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA /39 1. -

Gregory Kent1 Abstract: the 1992-95 War in Bosnia Was the Worst War on the European Continent Since WWII

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk SOLON Law, Crime and History - Volume 03 - 2013 SOLON Law, Crime and History - Volume 3, Issue 2 2013 Justice and Genocide in Bosnia: An Unbridgeable Gap Between Academe and Law? Kent, Gregory Kent, G. (2013) ' Justice and Genocide in Bosnia: An Unbridgeable Gap Between Academe and Law?',Law, Crime and History, 3(2), pp.140-161. Available at: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/handle/10026.1/8884 http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/8884 SOLON Law, Crime and History University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Law, Crime and History (2013) 2 JUSTICE AND GENOCIDE IN BOSNIA: AN UNBRIDGEABLE GAP BETWEEN ACADEME AND LAW? Gregory Kent1 Abstract: The 1992-95 war in Bosnia was the worst war on the European continent since WWII. The massive and systematic human rights violations were the worst in Europe since the Holocaust. This article proposes, based on a provisional review of non-legal, mainly social science and humanities literature on the Yugoslav crisis, and on a focused analysis of genocide jurisprudence, that there is a gulf between, on the one hand, academic interpretations of these human rights violations as constituting genocide – with some notable exceptions - and on the other, judicial decisions regarding cases brought at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (and partly the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda - ICTR). -

Rethinking Srebrenica

RETHINKING SREBRENICA Stephen Karganović Ljubiša Simić RETHINKING SREBRENICA Stephen Karganović Ljubiša Simić Unwritten History, Inc. New York, New York Rethinking Srebrenica (originally published as Deconstruction of a Virtual Genocide) First published 2013. Copyright © 2013 by Stephen Karganović and Ljubiša Simić. Certain copyrighted materials have been quoted here under the Fair Use provi- sions of the U.S. Copyright Act (Section 107) which permits the use of copy- righted materials for the purposes of criticism, comment, news, reporting, and teaching. Every effort has been made by the publisher to trace the holder of the copyright for the illustration used on the front cover. As it stands now, the source re- mains unknown. This omission will be rectified in future editions. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, re- cording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to: Unwritten History, Inc. UPS Store #1052 PMB 199, Zeckendorf Towers 111 E. 14th Street New York, NY 10003 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.unwrittenhistory.com ISBN: 978-0-9709198-3-0 Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................. vii I. SREBRENICA: A CRITICAL OVERVIEW ...................... 15 II. DEMILITARIZATION OF THE UN SAFE ZONE OF SREBRENICA ............................................................. 53 III. GENOCIDE OR BLOWBACK? ...................................... 75 IV. GENERAL PRESENTATION AND INTERPRETATION OF SREBRENICA FORENSIC DATA (PATTERN OF INJURY BREAKDOWN) ............ 108 V. AN ANALYSIS OF THE SREBRENICA FORENSIC REPORTS PREPARED BY ICTY PROSECUTION EXPERTS ........ -

Statut Opstine Srebrenica

OSNA I HERCEGOVINA/БОСНА И ХЕРЦЕГОВИНА BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA REPUBLIKA SRPSKA/РЕПУБЛИКА СРПСКА REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA ОPŠTINA SREBRENICA/ОПШТИНА СРЕБРЕНИЦА MUNICIPALITY OF SREBRENICA NAČELNIK OPŠTINE/НАЧЕЛНИК ОПШТИНЕ MAYOR OF MUNICIPALITY Adresa: Srebreničkog odreda bb, Adress: Srebrenickog odreda bb, Адреса: Сребреничког одреда бб, Tel: 056/445–514, 445–501 Tel/Тел: 056/445–514, 445–501 Fax: 056/445–233 Faks/Факс: 056/445–233 Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.srebrenica.gov.ba Web: www.srebrenica.gov.ba Srebrenica:14.05.2018.godine Broj: 01-022- /18 Na osnovu člana 39. i 82. Stav 2. Zakona o lokalnoj samoupravi („Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske“, broj: 97/16), Skupština opštine Srebrenica na VII tematskoj sjednici održanoj dana 11.05.2018. na prijedlog Načelnika opštine d o n o s i STATUT OPŠTINE SREBRENICA I OSNOVNE ODREDBE Član 1. (1) Ovim statutom uređuju se područje, sjedište i simboli opštine Srebrenica kao jedinice lokalne samouprave, teritorijalna organizacija, mjesne zajednice, način i uslovi njihovog formiranja, poslovi opštine Srebrenica, osnivanje i uređenje Opštinske uprave, organizacija i rad njenih organa, nadzor nad radom organa Opštine, odbor za žalbe, primopredaja dužnosti, akti i finansiranje, javnost rada, oblici učešća građana u lokalnoj samoupravi, odnos Republičkih organa i Opštine, zaštita prava Opštine, saradnja sa drugim jedinicama lokalne samouprave i drugim institucijama, prekogranična i međunarodna saradnja, postupak za izmjenu i donošenje statuta opštine Srebrenica (u daljem tekstu: statut opštine ), prava i dužnosti zaposlenih u Opštinskoj upravi i druga pitanja od lokalnog interesa u skladu sa zakonom. (2) Gramatički odnosno pojedini izrazi upotrebljeni u ovom statutu za označavanje muškog ili ženskog roda podrazumijevaju oba pola. -

Bosnian Genocide Denial and Triumphalism: Origins

BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION IMPACT ORIGINS, DENIAL ANDTRIUMPHALISM: BOSNIAN GENOCIDE BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION Illustration © cins Edited by Sead Turčalo – Hikmet Karčić BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION PUBLISHER Faculty of Political Science University of Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina IN COOPERATION WITH Srebrenica Memorial Center Institute for Islamic Tradition of Bosniaks ON BEHALF OF THE PUBLISHER Sead Turčalo EDITORS Hikmet Karčić Sead Turčalo DTP & LAYOUT Mahir Sokolija COVER IMAGE Illustration produced by Cins (https://www.instagram.com/ cins3000/) for Adnan Delalić’s article Wings of Denial published by Mangal Media on December 2, 2019. (https://www.mangalmedia.net/english//wings-of-denial) DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions of Publishers or its Editors. Copyright © 2021 Printed in Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnian Genocide Denial and Triumphalism: Origins, Impact and Prevention Editors: Sead Turčalo – Hikmet Karčić Sarajevo, 2021. Table of Contents Preface ..............................................................................7 Opening Statement by Ambassador Samantha Power .....9 PETER MAASS: The Second War: Journalism and the Protection of the Memory of Genocide From the Forces of Denial ..........................................15 MARKO ATTILA HOARE: Left-Wing Denial of the Bosnian Genocide ................................20 SAMUEL TOTTEN: To Deny the Facts of the Horrors of Srebrenica Is Contemptible and Dangerous: Concrete Recommendations to Counter Such Denial ...27 NeNad dimitrijević: Life After Death: A View From Serbia ....................................................36 ediNa Bećirević: 25 Years After Srebrenica, Genocide Denial Is Pervasive. It Can No Longer Go Unchallenged .........................42 Hamza Karčić: The Four Stages of Bosnian Genocide Denial .........................................................47 DAVID J. -

Foca Zrtva Genocida.Pdf

Izdavač: Institut za istraživanje zločina protiv čovječnosti i međunarodnog prava Univerziteta u Sarajevu Za Izdavača: Prof. dr. Smail Čekić Urednik: Milan Pekić Recenzent: Dr. Esad Bajtal cip Štamparija: XXXXXXXXXXX Tiraž: XXXX MUJO KAFEDŽIĆ FOČA, ŽRTVA GENOCIDA XX VIJEKA Sarajevo, 2011. „Iskustvo je korisno, ali ima manu – – nikad se ne ponavlja na isti način“ Čerčil Ova knjiga nije namijenjena podgrijavanju nacionali- stičkih, kao ni osvetničkih strasti. Date podatke treba koristiti kao svjedočanstvo o vremenu nacionalističkih ludosti i morbidnim stranama ljudske ličnosti. Treba ih shvatiti kao upozorenje i opo- menu. Mora, jednom i konačno, pobijediti svijest o životu i slozi, zajedničkom radu za i na sreću svih ljudi. Autor Riječ urednika Istina bez teka, moralni zakoni i zvjezdano nebo nad nama ovoj knjizi riječ je i o onome o čemu se nerado razgovaralo u prohujalih pe- desetak, nešto više, pa čak, ako je bilo znalaca, i hiljadu godina. I onome Ušto jeste rečeno, već je i dokazivano i djelomice potvrđeno. Ukratko, riječ je o, a bolno je, povijesnom derivatu „cijeđenja“ Bosne i onome što nije, do kraja, objekti- vizirano i ovjereno pečatom istine, pravde i pravednosti. Upravo zbog društvene šutnje i sudara iskustava, manje ili više dokumentirane predaje i, dakako, interesa, kraj prethodne rečenice, izazivat će rogušenja oko dva navedena pojma: Pravda i pravednost. U, inače gotovo generalnom i uobičajenom politiziranju, tako svojstvenom ljudima ovih prostora, često se zaboravi, smetne ili, što da se dalje oko pravog termina kruži, jedno- stavno ne zna da nisu u pitanju sinonimi. Da je riječ o dvije različite riječi, od kojih je svaka svoje snage i samo svog značenja! U leksičku istovjetnost bi se zakleli mnogi politikusi, profesionalci i oni drugi, u svakom slučaju nedovoljno obrazovani ljudi, ali, u svojoj uobraženosti,s „izgrađenim stavom“.