The Role of Culture in Interrogation and Questioning in the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Öffentliche Bekanntmachung Kreiswahl Am 12

Öffentliche Bekanntmachung Kreiswahl am 12. September 2021 im Landkreis Schaumburg Gemäß § 28 Abs. 6 des Niedersächsischen Kommunalwahlgesetzes i.d.F. vom 28.01.2014 (Nds. GVBl. S. 35), zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 10.06.2021 (Nds. GVBl. S. 368) und § 38 der Niedersächsischen Kommunalwahlordnung i.d.F. vom 05.07.2006 (Nds. GVBl. S. 280, 431), zuletzt geändert durch Verordnung vom 01.07.2021 (Nds. GVBl. S. 446), mache ich die für die Kreiswahl am 12. September 2021 im Landkreis Schaumburg zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge bekannt: Bewerberinnen und Bewerber im Wahlbereich 1 - Stadt Rinteln (1) Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) 1 Bredemeier, Birte Dipl.-Umweltwissenschaftlerin *1982 Rinteln 2 Ruhnau, Carsten Lehrer *1977 Rinteln 3 Kirchhoff, Bernd Systemadministrator *1971 Rinteln 4 Teigeler-Tegtmeier, Astrid Geschäftsführerin *1963 Rinteln 5 Schumann, Philipp Staatl. anerkannter Erzieher *1985 Rinteln 6 Berlitz, Linda Auszubildende *2001 Rinteln 7 Posnien, Volker Dipl.-Finanzwirt *1962 Rinteln 8 Neumann, Ursula Rentnerin *1951 Rinteln 9 Sprick, Burkhard Fachkrankenpfleger *1961 Rinteln 10 Mehrens, Petra Lehrerin *1960 Rinteln 11 Sander, Sebastian Bürokaufmann *1973 Rinteln 12 Künneke, Helmuth Rentner *1947 Rinteln (2) Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands in Niedersachsen (CDU) 1 Steding, Marion Dipl.-Bauingenieurin *1974 Rinteln 2 Rauch, Veit Fleischermeister *1968 Rinteln 3 Kretzer, Thorsten Rechtsanwalt *1969 Rinteln 4 Hoppe, Steffen Schüler *1998 Rinteln 5 Lee, Anthony-Robert Landwirt *1976 Rinteln 6 Seidel, Ulrich -

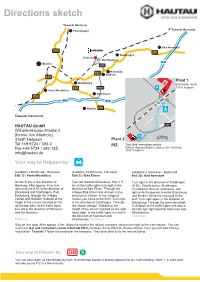

Directions Sketch

Directions sketch Towards Nienburg Petershagen Towards Hannover Bad Nenndorf 482 65 Stadthagen Helpsen S Kirchhorsten Minden 2 K19 Nienstädt 65 Sülbeck 65 Plant 1 Bückeburg Bahnhofstr. 56-60 83 L442 P 31691 Helpsen Porta Westfalica Bad Eilsen 482 2 2 S Rinteln 83 Towards Dortmund HAUTAU GmbH K19 Wilhelm-Hautau-Straße 2 (former Am Allerholz) P 100 m 31691 Helpsen Plant 2 Tel +49 5724 / 393-0 PIZ Test and innovation centre Wilhelm-Hautau-Straße 2 (former Am Allerholz) Fax +49 5724 / 393-125 31691 Helpsen [email protected] Your way to Helpsen by Autobahn 2 Dortmund - Hannover Autobahn 2 Dortmund - Hannover Autobahn 2 Hannover - Dortmund Exit 33 / Porta Westfalica Exit 35 / Bad Eilsen Exit 38 / Bad Nenndorf On the B 482 in the direction of Turn left towards Bückeburg. After 1.5 Turn right in the direction of Stadthagen Nienburg. After approx. 8 km turn km at the traffic lights turn right in the (B 65). Shortly before Stadthagen, right onto the B 65 in the direction of direction of Bad Eilsen. Through the immediately after an underpass, turn Bückeburg and Stadthagen. Past villages Bad Eilsen and Ahnsen in the right onto the bypass towards Bückeburg Bückeburg, through the villages direction of Vehlen. In the village of and Minden. Drive the ring road to the Vehlen and Gelldorf. Sülbeck at the Vehlen you come to the B 65. Turn right end. Turn right again in the direction of height of the church (located on the in the direction of Stadthagen. Through Bückeburg. Through the town Nienstädt. right hand side), at the traffic lights the village Gelldorf. -

Informationen Der SPD Aus Bad Nenndorf

Informationen der SPD aus Bad Nenndorf Haste Hohnhorst Suthfeld Dezember 2014 Nr. 88 AG 60plus Turbulenzen Trauer um in Brüssel in Hohnhorst Konrad Götze Zentrum: REWE kommt (VB) Die Neu- und Umbaupla- nungen der Part AG aus Bad Gandersheim als Investor für das Einkaufszentrum auf dem Ther- malbadparkplatz, bei dem das angrenzende Haus, in dem ehe- mals Plus ansässig war, mit ein- gebunden wird, sind abgeschlos- sen. Mit einem modernen Ausse- hen wird ein neuer Lebensmittel- markt entstehen, in den REWE mitten im Zentrum von Bad Nenndorf einziehen wird. Die Volksbank in Schaumburg wird in dem bislang leer stehenden Haus daneben ihr neues Domizil erhal- ten. Auf dem Parkdeck oberhalb des Einkaufsmarktes wird für das bisherige italienische Restaurant ein nahezu runder Pavillon ent- stehen. Eine Eisdiele an der Kur- Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, hausstraße rundet den Um- und seit über 30 Jahren versorgen wir Sie als SPD in Form unseres Bürgerbriefes Neubau ab. Über 80 Parkplätze mit wichtigen und lesenswerten Informationen aus der ganzen Samtgemeinde werden weiterhin für die Öffent- Nenndorf. Unser Ziel ist es, dass jeder Haushalt unabhängig von der Tageszei- lichkeit frei zur Verfügung stehen. tung und dem Internet über die aktuellen Geschehnisse vor seiner Haustüre Die Bauarbeiten sollen im Januar bestens informiert ist. Daher ist uns auch besonders Ihre Meinung wichtig und 2015 beginnen. wir freuen uns jederzeit über Kritik, Anregungen oder Fragen - die Kontaktda- ten entnehmen Sie bitte der letzten Seite. „Die Optik mit dem runden Res- Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Spaß beim Lesen und insbesondere frohe Weihnach- taurant an der Ecke zur Kurhaus- ten und einen guten Rutsch ins neue Jahr! straße wurde nach intensiven Gesprächen mit dem Investor Ihr Bürgerbrief-Redaktionsteam und der SPD-Fraktion noch ein- geplant. -

Fall/Winter 2018

FALL/WINTER 2018 Yale Manguel Jackson Fagan Kastan Packing My Library Breakpoint Little History On Color 978-0-300-21933-3 978-0-300-17939-2 of Archeology 978-0-300-17187-7 $23.00 $26.00 978-0-300-22464-1 $28.00 $25.00 Moore Walker Faderman Jacoby Fabulous The Burning House Harvey Milk Why Baseball 978-0-300-20470-4 978-0-300-22398-9 978-0-300-22261-6 Matters $26.00 $30.00 $25.00 978-0-300-22427-6 $26.00 Boyer Dunn Brumwell Dal Pozzo Minds Make A Blueprint Turncoat Pasta for Societies for War 978-0-300-21099-6 Nightingales 978-0-300-22345-3 978-0-300-20353-0 $30.00 978-0-300-23288-2 $30.00 $25.00 $22.50 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS 1 General Interest COVER: From Desirable Body, page 29. General Interest 1 The Secret World Why is it important for policymakers to understand the history of intelligence? Because of what happens when they don’t! WWI was the first codebreaking war. But both Woodrow Wilson, the best educated president in U.S. history, and British The Secret World prime minister Herbert Asquith understood SIGINT A History of Intelligence (signal intelligence, or codebreaking) far less well than their eighteenth-century predecessors, George Christopher Andrew Washington and some leading British statesmen of the era. Had they learned from past experience, they would have made far fewer mistakes. Asquith only bothered to The first-ever detailed, comprehensive history Author photograph © Justine Stoddart. look at one intercepted telegram. It never occurred to of intelligence, from Moses and Sun Tzu to the A conversation Wilson that the British were breaking his codes. -

Informationen Der SPD Aus Bad Nenndorf Haste Hohnhorst Suthfeld

Informationen der SPD aus Bad Nenndorf Haste Hohnhorst Suthfeld Dezember 2015 Nr. 90 AG 60plus Ferienspaßaktionen Neue Bürgermeisterin wählt neuen Vorstand WoKi 2015 in Suthfeld SPD Bad Nenndorf setzt sich „Stadtmarketing ist ebenso weiterhin für ein Stadtmarketing nach außen auf Tourismus und ein ansiedlungswillige Unterneh- mer zu richten, wie nach innen (VB) „Kein Stadtmarketing in auf Einwohner und ansässige Bad Nenndorf erwünscht“, so Unternehmer sowie die Mitar- die Kurzformel, die Volker Bus- beiter der Verwaltung, die wich- se, SPD-Fraktionsvorsitzende tige Träger der Zusammenar- im Stadtrat Bad Nenndorf, ver- beit beim Stadtmarketing sind“, ärgert vorträgt. Die Mehrheit im so Gudrun Olk, Bürgermeisterin Verwaltungsausschuss Bad in Bad Nenndorf. Nenndorf hat den Vorschlag der SPD, in Bad Nenndorf ein Nach dem Zusammenbruch Stadtmarketing einzuführen, des klassischen Kurbetriebs mit abgelehnt. dem dauerhaften Verlust von zahllosen Arbeitsplätzen und Bereits im November 2013 hat- der Teilkommunalisierung des te die SPD-Stadtratsfraktion Staatsbades vor einigen Jahren beantragt, einen Stadtmarke- besteht weitgehend Unklarheit tingprozess einzuleiten und darüber, in welche Richtung dafür entsprechende Haus- sich Bad Nenndorf entwickeln haltsmittel aufzunehmen. Im soll. Da in wenigen Jahren die Haushalt 2015 wurde sogar ein jährlichen Zuschüsse des Lan- Betrag von 20.000 Euro neben des auslaufen und auch andere weiteren Mitteln aus der Städte- Fördermitteltöpfe (z.B. Städte- bauförderung eingeplant. bauförderung) nicht dauerhaft zur Verfügung stehen werden, Dabei waren schon 2014 we- wird die Stadt schon in näherer sentliche Schritte von der Ver- Zukunft ohne Hilfe von außen waltung vorbereitet worden: weitestgehend auf sich allein externe Fachberater sollten ihre gestellt sein und sich Gedan- Frohe Weihnachten wünscht Ihnen der Überlegungen für ein Bad ken für die weitere Gestaltung SPD-Samtgemeindeverband Nenndorf! Nenndorfer Stadtmarketing den des Ortes machen müssen. -

Annual 2017-2018

T H E E H K E T N KENSINGTON S I N G T SOCIETY O N 2017 –2018 S O C I E T Y 2 0 1 7 – 2 0 1 8 £5 for non-members KENSINGTON & CHELSEA The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea was created in 1965 with the merger of the two boroughs. Kensington, the area we watch over on your behalf, is north of Fulham Road and Walton Street, the frontier with Chelsea being marked with a red line on the map. Cover illustrations by Eileen Hogan, © the artist – for more about her see page 16 Editor: Michael Becket [email protected] Designer: Ian Hughes www.mousematdesign.com Printed by KJS Print Services Limited E H T KENSINGTON 23 St James’s Gardens, London W11 4RE www.kensingtonsociety.org SociETy 2017–2018 The objects of the society are to preserve and improve the amenities of Kensington for the public benefit by stimulating interest in its history and records, promoting good architecture and planning in its development, and by protecting, preserving and improving its buildings, open spaces and other features of beauty or historic interest. Patron His Royal Highness The Duke of Gloucester, KG, GcVo President Nick Ross Vice-President General, The Lord Ramsbotham of Kensington, GcB, cBE council Barnabus Brunner Peter De Vere Hunt Susan Lockhart Sir Angus Stirling trustees Amanda Frame, chairman Martin Frame, treasurer and membership secretary Michael Bach, chairman of the planning committee Michael Becket, annual report editor Thomas Blomberg, editor of newsletter and website, member of planning committee Sophia Lambert, member of the planning committee -

Informationen Der SPD Aus Bad Nenndorf Haste Hohnhorst Suthfeld

Informationen der SPD aus Bad Nenndorf Haste Hohnhorst Suthfeld Juli 2020 Nr. 94 Die Corona-Pandemie - ein Denkan- • Wie gut ist ein Wirtschaftssystem, Die Diskussion ist eröffnet. Aus sozial- stoß das 365 bzw. 366 Tage im Jahr auf demokratischer Sicht kann nur eine Hochtouren laufen muss, damit es solidarische Verteilung der Kosten er- Im Dezember vergangenen Jahres funktioniert? folgen. Kleine und mittlere Unterneh- wurde das SARS-CoV-2-Virus in der Ein kleines Virus hat das ganze Sys- men, Arbeitnehmer*innen, Pflegekräf- chinesischen Provinz Wuhan entdeckt. tem zumindest stark getroffen. Wieder te, Eltern, Pflegebedürftige u.v.m. ha- Seinerzeit rechneten wohl die wenigs- einmal zeigt sich, dass die Schwächs- ben schon jetzt einen gewichtigen Bei- ten damit, dass dieses Virus einige ten der Gesellschaft diejenigen sind, trag geleistet. Wochen später die ganze Welt in Atem die am stärksten leiden. Sowohl ge- • Wie kommt Deutschland ökonomisch hält. sundheitlich, zwischenmenschlich als aus der Pandemie? Ob er sie auch nachhaltig verändern auch wirtschaftlich. Sämtliche Hilfs- Im internationalen Vergleich steht wird, muss die Zeit zeigen. Die Gefähr- maßnahmen sind darauf ausgerichtet, Deutschland gut da. Die von der Bun- lichkeit des Virus wurde bereits in den ökonomischen Status, der vor der des– und Landesregierung eingeleite- Wuhan deutlich. Es schien noch weit Pandemie herrschte, wieder zu errei- ten Hilfsmaßnahmen wurden weitest- weg. Erst die Bilder aus Norditalien chen. Was wir definitiv wissen, ist, gehend gut umgesetzt. sorgten für ein Umdenken. Im März dass die nächste Pandemie kommen Beides ist auch einer funktionsfähigen kam es dann auch in Deutschland zu kann und diese dann nicht mehr mit Verwaltung zu verdanken. -

The Executioner at War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors

The Executioner At War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors lbert Pierrepoint was not called up when war broke out. But there were war-related changes for him as well. Not only murderers and A murderesses could now be punished by death, there were sentences under the Treason Act and Treachery Act as well, both imposing »death« as the maximum penalty. The Treason Act went back to an ancient law of King Edward III's time (1351). »Treason« was, first of all, any attack on the legitimate ruler, for instance by planning to murder him, or on the legitimacy of the succession to the throne: It was treason as well if someone tried to smuggle his genes into the royal family by adultery with the queen, the oldest daughter of the king or the crown prince’s wife. This aspect of the law became surprisingly topical in our days: When it became known that Princess Diana while married to the Prince of Wales had had an affair with her riding instructor James Hewitt, there were quite some law experts who declared this to be a case of treason – following the letter of the Act, it doubtlessly was. However as it would have been difficult to find the two witnesses prescribed by the Act, a prosecution was never started. Just Hewitt’s brother officers of the Household Cavalry did something: They »entered his name on the gate« which was equivalent to drumming him out of the regiment and declaring the barracks off limits for him.317 During World War II, it became important that a person committed treason if they supported the king’s enemies in times of war. -

Military History

Save up to 80% off cover prices on these subjects: Air Combat & Aircraft ···················45 Military Modeling·······················68 American Military History··················8 Naval History ·························59 American Revolution ····················10 Notable Military Units····················57 British Military History ···················67 Spies & Espionage ·····················65 Civil War ·····························12 Uniforms, Markings & Insignia ·············56 Cold War ····························66 Vietnam War ··························15 European Warfare ······················67 WW I & WW II Battles & Campaigns ·········34 Fortresses & Castles ····················59 WW I & WW II Commanders & Units ········39 General Military History ···················2 WW I & WW II Diaries & Memoirs···········30 History of Warfare······················63 WW I & WW II Naval History ··············41 Hitler & the Nazis·······················26 WW I & WW II Spies & Espionage ··········44 Holocaust ····························29 War on Terror ·························67 Korean War···························15 Wartime Journalism ····················64 Military Collectibles ·····················68 Weapons & Military Technology ············58 Military Leaders························69 World War I & World War II ···············18 Current titles are marked with a «. 3891682 SWORD TECHNIQUES OF MUSASHI AND THE OTHER SAMURAI General Military History MASTERS. By Fumon Tanaka. An internationally LIMITED QUANTITY 4724720 SILENT AND renowned -

The Secret Listeners

The Secret Listeners The Secret Listeners Pascal Theatre Company The Secret Listeners Edited by Julia Pascal and Thomas Kampe Pascal Theatre Company ‘The project set out to investigate little Edited by Julia Pascal and Thomas Kampe known events that happened during World War II at the large mansion house in Trent Park ..... What was the particular history that had been hidden for so long?’ ‘A site-specific investigation, a series of interviews with refugees and locals, a learning process and training for volunteers, a film, a public discussion, a new research document, a website, a book and much more.’ Julia Pascal ‘The performance event central to this heritage educational project was conceived as a site-responsive tour, as a promenade-like immersive experience for the spectators as active, emancipated participants.’ Thomas Kampe The Secret Listeners Pascal Theatre Company Edited by Julia Pascal and Thomas Kampe A Brief History 7 Julia Pascal From Black Box to Open House 11 What is Political Theatre? Julia Pascal Listening as Learning 21 Thomas Kampe An Emerging Vision: Secret Listeners 23 Working Methods Thomas Kampe Partnerships 41 The Wiener Library and The Jewish Military Museum Research and Future Questions 45 Sally Mijit ATrentParkHistory 67 Melvyn Keen Reflections 73 Jonathan Meth, Mark Norfolk, Del Taylor, Susannah Kraft Levene, Wayne McGee and Lesley Lightfoot Credits 86 Julia Pascal ABriefHistory This book gives an insight into a heritage arts educational project undertaken in 2012-2013 by Pascal Theatre Company. The Secret Listeners was made possible by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF). The project set out to investigate little known events that happened during World War II at the large mansion house in Trent Park, and from that exploration, several strands of educational work, which ran parallel to different activities during 2012 and 2013. -

Helen Fry. the London Cage: the Secret History of Britain's World War II Interrogation Centre

This is a repository copy of Helen Fry. The London Cage: The Secret History of Britain's World War II Interrogation Centre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/144147/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, B. (2018) Helen Fry. The London Cage: The Secret History of Britain's World War II Interrogation Centre. Journal of British Studies, 57 (3). pp. 650-651. ISSN 0021-9371 https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2018.63 This article has been published in a revised form in Journal of British Studies [https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2018.63]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © The North American Conference on British Studies 2018. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Helen Fry, The London Cage. The Secret H Bs World War II Interrogation Centre New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017) HB pp. -

Review-The-London-Cage.Pdf

Intelligence in Public Media The London Cage: The Secret History of Britain’s WWII Interrogation Centre Helen Fry (Yale University Press, 2017), 244 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index. Reviewed by J. R. Seeger In 1929, the great powers of Europe met in Geneva 1939 and the 1940 German invasion of Holland, Belgium, to address issues related to handling both prisoners and and France that it became clear this conflict was unlike civilians during any future war. The Geneva Convention, any other. It is no exaggeration to state that by the fall of officially titledThe Convention Relative to the Treatment 1940, the British government and people felt they were of Prisoners of War, had 97 articles addressing every facing an existential threat from the Nazi war machine. aspect of the treatment of captured warfighters, as well as civilians, in areas occupied by a hostile military force. Further, while the full scope of the Nazi genocide The destructive power unleashed during World War I— against Jewish and other ethnic and religious groups in the first modern war—surpassed the imagination of Germany proper and the areas Germany occupied were leaders on all sides of the conflict. Still, in 1929, Europe- not immediately evident, it was clear by 1940 that the an and US leaders had an almost chivalrous image of how Nazi regime was not abiding by the Geneva Convention the victorious should (and would) treat prisoners of war, with regard to civilians. In July 1942, Field Marshal best characterized in Article 5 of the convention, which Gerd von Rundstedt issued an order instructing all Allied states, parachutists to be turned over immediately to the Gestapo for interrogation and subsequent execution.