The Executioner at War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association of Clinical Pathologists

The Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists Number 163 July 2013 In this issue The Royal College of Pathologists Everything you wanted to know about your new Pathology: the science behind the cure consultant post but were afraid to ask Voice recognition in histopathology: pros and cons Public Engagement Innovation Grant Scheme www.rcpath.org/bulletin Subscribe to the Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists The College’s quarterly membership journal, the Bulletin, is the main means of communications between the College and its members, and between the members themselves. It features topical articles on the latest development in pathology, news from the College, as well as key events and information related to pathology. The Bulletin is delivered free of charge to all active College Members, retired Members who choose to receive mailings and Registered Trainees, and is published four times a year, in January, April, July and October. It is also available for our members to download on the College website at www.rcpath.org/bulletin The subscription rate for libraries and non-members is £100 per annum. To subscribe, contact the Publications Department on 020 7451 6730 or [email protected] Sign up today and keep up to date on what goes on in the world of pathology! The Royal College of Pathologists 2 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AF telephone 020 7451 6700 email [email protected] website www.rcpath.org President Dr Archie Prentice Vice Presidents Dr Bernie Croal Dr Suzy Lishman Professor Mike Wells Registrar Dr Rachael -

Leyland Historical Society

LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No. 1024919 PRESIDENT Mr. W. E. Waring CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Mr. P. Houghton Mrs. E. F. Shorrock HONORARY SECRETARY HONORARY TREASURER Mr. M. J. Park Mr. E. Almond Tel: (01772) 337258 AIMS To promote an interest in history generally and that of the Leyland area in particular MEETINGS Held on the first Monday of each month (September to July inclusive) at 7.30 pm in The Shield Room, Banqueting Suite, Civic Centre, West Paddock, Leyland SUBSCRIPTIONS Vice Presidents: £10.00 per annum Members: £10.00 per annum School Members: £1.00 per annum Casual Visitors: £3.00 per meeting A MEMBER OF THE LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE and THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR LOCAL HISTORY Visit the Leyland Historical Society's Web Site at: http//www.leylandhistoricalsociety.co.uk C O N T E N T S Page Title Contributor 4 Editorial Mary Longton 5 Society Affairs Peter Houghton 7 From a Red Letter Day to days with Red Letters Joan Langford 11 Fascinating finds at Haydock Park Edward Almond 15 The Leyland and Farington Mechanics’ Institution Derek Wilkins Joseph Farington: 3rd December 1747 to Joan Langford 19 30th December 1821 ‘We once owned a Brewery’ – W & R Wilkins of Derek Wilkins 26 Longton 34 More wanderings and musings into Memory Lane Sylvia Thompson Railway trip notes – Leyland to Manchester Peter Houghton 38 Piccadilly Can you help with the ‘Industrial Heritage of Editor 52 Leyland’ project? Lailand Chronicle No. 56 Editorial Welcome to the fifty-sixth edition of the Lailand Chronicle. -

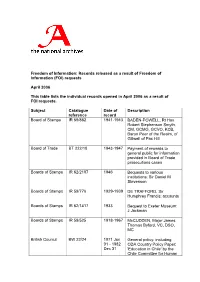

FOI) Requests

Freedom of Information: Records released as a result of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests April 2006 This table lists the individual records opened in April 2006 as a result of FOI requests. Subject Catalogue Date of Description reference record Board of Stamps IR 59/882 1941-1943 BADEN-POWELL, Rt Hon Robert Stephenson Smyth, CM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB, Baron Peer of the Realm, of Gillwell of Pax Hill Board of Trade BT 222/10 1943-1947 Payment of rewards to general public for information provided in Board of Trade prosecutions cases Boards of Stamps IR 62/2197 1946 Bequests to various institutions: Sir Daniel M Stevenson Boards of Stamps IR 59/776 1929-1939 DE TRAFFORD, Sir Humphrey Francis: accounts Boards of Stamps IR 62/1417 1933 Bequest to Exeter Museum: J Jackman Boards of Stamps IR 59/525 1918-1967 McCUDDEN, Major James Thomas Byford, VC, DSO, MC British Council BW 22/24 1971 Jan General policy: including 01 - 1982 ODA Country Policy Paper; Dec 31 'Education in Chile' by the Chile Committee for Human Rights Courts Martial WO 71/1105 1945 Harpley, DA Offence: Rape Courts Martial AIR 18/50 1966 Feb Sgt Kelly, A B. Offence: 21 Murder. (Conviction later quashed) Crime HO 1922 CRIMINAL CASES: 144/1754/425994 ARMSTRONG, Herbert Rowse Convicted at Hereford on 13 April 1922 for murder and sentenced to death Crime HO 144/22540 1926-1946 CRIMINAL: Michael Dennis Corrigan alias Edward Kettering alias Kenneth Edward Cassidy: confidence trickster. Crime HO 144/14913 1931 CRIMINAL: Unsolved murder of Louisa Maud Steele at Blackheath: alleged confession by Arthur James Faraday Salvage, murderer of Ivy Godden. -

Mount Robson – 1961

238 T h e A l p i n e J o u r n A l 2 0 1 4 for treason at the Old Bailey in late November 1945, pleading guilty to eight counts of high treason and sentenced to death by hanging. He did TED NORRISH this in order to spare his family any more embarrassment, but the papers at Cambridge show how Amery and his younger son Julian tried every way they could to save his life. Despite a psychiatric report by an eminent Mount Robson – 1961 practitioner, Dr Edward Glover, that he was definitely abnormal with a psychopathic disorder and schizoid tendencies, and the intervention of the South African Field Marshall General Jan Smuts, an AC member, who pleaded directly for clemency with the UK Prime Minister Clement Atlee, it was to no avail. Albert Pierrepoint, the public hangman, described John Amery in his autobiography as the bravest man he had to execute. However, germane to this tragedy, considered by Ronald Harwood as significant to John Amery’s story, is that his father had concealed his part- Jewish ancestry. His mother, Elizabeth Leitner, was actually from a family of well-known Jewish scholars. Leo Amery lost his seat in Parliament in the Labour landslide victory in the General Election of 1945, and refused the offer of a peerage. He was however made a Companion of Honour. Leo kept active in climbing circles almost to the end of his life, ignoring the advice of his old Canadian friend, Wheeler, who, quoting Whymper, advised him in a letter that, ‘a man does not climb mountains after his 60th year’. -

Albert Pierrepoint and the Cultural Persona of the Twentieth- Century Hangman

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Sussex Research Online Albert Pierrepoint and the cultural persona of the twentieth- century hangman Article (Accepted Version) Seal, Lizzie (2016) Albert Pierrepoint and the cultural persona of the twentieth-century hangman. Crime, Media, Culture, 12 (1). pp. 83-100. ISSN 1741-6590 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/60124/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Introduction Despite his symbolic importance, the figure of the English hangman remains largely ignored by scholars.1 In an article dating from the mid-s, ‘oi : oted that it is supisig that geate attetio has ot ee dieted to the eeutioe ad this oseatio eais petiet. -

The Executioners at Bodmin Jail

The Executioners at Bodmin Jail From the building of Bodmin Gaol in 1779 there have been a total of 55 executions carried out; a good number of them for what we consider today as petty offences. Over the years there have been many hangmen invited by the authorities to carry out the execution of the unfortunate condemned. Some hangmen would have been prisoners who were themselves condemned; they were given a chance of reprieve if they carried out the execution if no hangman could be brought in. One of the earliest recorded hangmen is George Mitchell, who hailed from Cork Gates, Ilchester, Somersetshire. Records indicate that George Mitchell was a hangman from 1800 until 1854. This would seem to be incorrect, as no one hangman has ever served this length of time. It would probably be that the original George Mitchell had his son assist him at hangings and the name carried on, as his son would then have become hangman for the South West. In 1840 George Mitchell was to hang the Lightfoot brothers for the murder of Neville Norway. The report states that he was dressed as a respectable yeoman, and that he was a hoary headed man who was a dairy farmer. Unfortunately there is no picture or portrait of George Mitchell in existence, but we do have a copy of one of his receipts for the hanging of Benjamin Ellison on The 11 th August 1845. This was to be George Mitchell’s last hanging at Bodmin Jail. The Executioners at Bodmin Jail Executions at Bodmin Jail were quite a rarity, and the authorities were not keen to keep another hangman on a salary mainly for doing nothing. -

The Role of Culture in Interrogation and Questioning in the Second World War

DOSSIER War and Post-War Periods in Late Modern Europe Close Encounters: the role of culture in interrogation and questioning in the Second World War Simona TOBIA University College London Lyman B. Kirkpatrick spent the Second World War in the American intelligence, working for G-2 and for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). After the war he served in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and became executive director in 1961. He was also a prolific writer and in 1961 he wrote for the CIA a report titled “Combat Intelligence: a comparative report” which focused on WWII and had the purpose to: “obtain first-hand judgments from intelligence officers at all levels about what methods of intelligence collection had proved most valuable in combat”. Unlike us historians, he was able to access sources only available to a CIA officer, including classified documents, visits to G-2 sections of all the armies that had served in the war to conduct interviews and submit questionnaires, and he found that By far the most profitable source of intelligence for all levels of the command – division, corps, and army – was prisoners of war. Some units estimated that as high as 90 per cent of their useful information came from prisoner interrogation. The corps calculated that from 33 to 50 per cent of all the information they received was provided by the interrogators in the prisoner-of-war cages1. Historians studying intelligence in the Second World War have traditionally 69 focused on signals intelligence (SIGINT): the impact of programs such as ULTRA, institutions such as the British Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park and devices such as the Enigma machine in breaking encrypted enemy communications are well known by the public beyond academic circles, and so are the networks of spies and the famous ‘double-cross system’. -

The Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum, Wandsworth Common

THE ROYAL VICTORIA PATRIOTIC ASYLUM, WANDSWORTH COMMON Simon McNeill-Ritchie SUMMARY was Wandsworth Common in South London, where a vast wooden amphitheatre had For almost one hundred years the Royal Victoria been constructed for thousands of VIPs Patriotic Asylum (later ‘School’) on Wandsworth and invited guests. The occasion was the Common, South London, was the nation’s principal foundation ceremony of the Royal Victoria orphanage for the daughters of British servicemen Patriotic Asylum, a military orphanage killed on duty. During World War I the building for the daughters of soldiers, sailors and also served as the Third London General Hospital, marines (Fig 1). On her arrival, Queen one of the capital’s ‘Big Four’ Territorial hospitals. Victoria processed along a red carpet to a Later, during the Second World War, the building covered platform at the centre of the arena. functioned as the London Reception Centre, the That evening in her journal, she described MI5 interrogation centre to which all male foreign the ceremony: nationals were brought immediately on arrival in the UK from occupied Europe. The building survives to The Archbishop read a Prayer, after which this day, and prompted by the 150th anniversary of Albert, as head of the Commission read its opening in 2009, this paper summarises the history a long address, to which I responded. of the building from its origins in the Crimean War Then, the stone was laid, Bands playing, until the removal of the orphanage to new premises in & guns firing & we returned as we came. Hertfordshire after 1945. May their good work, which is to bear my As well as creating a record of developments to the name, prosper! building and the different uses to which it was put, this The building was commissioned by the Royal paper aims to provide unique insights into life within Victoria Patriotic Fund, a popular appeal the building. -

2018 | 1 Matthias Bode, Traumsommer Und Kriegsgewitter

2018 | 1 Matthias Bode, Traumsommer und Kriegsgewitter. Die 19./20. Jahrhundert – Histoire politische Bedeutung des schönen Sommers 1914, Frankfurt contemporaine a. M. (Peter Lang Edition) 2016, 343 S., 15 s/w Abb., 7 DOI: Tab. (Geschichtsdidaktik diskursiv – Public History und 10.11588/frrec.2018.1.45575 Historisches Denken, 2), ISBN 978-3-631-67702-5, EUR Seite | page 1 69,95. rezensiert von | compte rendu rédigé par Annika Mombauer, Milton Keynes How would our collective memory of the outbreak of the First World War have differed if Archduke Franz Ferdinand had not been assassinated in the summer of 1914, and if the international crisis that followed had not occurred during exceptionally warm and pleasant weather, but in a foggy February or a rainy October? The outcome of the crisis may have been similar, notwithstanding the fact that military decision makers did of course have to pay heed to the seasons. But contemporaries would have told the story of the outbreak of war without the familiar metaphor of a glorious summer which was cruelly overshadowed by storm clouds as international tensions heightened until they were finally »discharged« in an electric storm, i. e. war. In his interesting investigation of the meaning, importance and longevity of the »dream summer« metaphor, Matthias Bode makes a convincing case that it certainly »would have been a different story« (p. 42) if war had broken out at a different time of year. Bode has painstakingly researched how and why contemporaries and later commentators used the image of the »glorious summer« of 1914. Using diaries, letters, autobiographies, novels and later accounts by historians, he shows convincingly that the metaphor of the »dream summer« encompassed many important and recurring themes: it speaks of innocence and surprise, and of regretful longing for a more peaceful past. -

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Adams, D. L. “The White

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Adams, D. L. “The White Rose: An Interview with Mrs. Suzanne Zeller-Hirzel.”, New English Review, Oct. 2009, https://www.newenglishreview.org/DL_Adams/The_White_Rose%3A_An_Interview_wi th_Mrs_Susanne_Zeller-_Hirzel/. Accessed 17 May 2020. This website contains excerpts from the leaflets that were personally written by members of the White Rose as well as an interview conducted with one of the two survivors of the White Rose organization, Suzanne Zeller. She explained her experience in the White Rose and how religion impacted the thinkings of the German people. Feder, Gottfried. “Program of the National Socialist Workers’ Party and it’s General Conceptions.” Internet Archive, 1932, https://archive.org/details/GottfriedFeder_TheProgramOfTheNSDAP. Accessed 17 January 2020. This is a translated version of The Program of the NSDAP, explaining Hitler’s rise to power, as well as, transferring his ideology into a plan of action to improve Germany in a short period of time, including his plans of unifying German citizens. This source allowed me to understand the rise of anti-semitism within Germany, which eventually led to the Holocaust. Huber, Wolfgang. E-mail message to son of White Rose member Professor Kurt Huber. May 21, 2020. This is a personal interview I was able to conduct with the child of one of the main members of the White Rose, Professor Kurt Huber. He explained the professor’s role in the group and how he worked with his students to protest against the wrongdoings of the government. Kittan, Tomas, director. “I Am the Last White Rose: BILD Visited Traute LaFrenz (99) in the USA.” YouTube, BILD, 28 Aug. -

Bayerns Letzter Henker Johann Baptist Reichhart (* 29

Bayerns letzter Henker Johann Baptist Reichhart (* 29. April 1893 in Wichenbach bei Wörth an der Donau; † 26. April 1972 in Dorfen bei Erding) war von 1924 bis 1946 staatlich bestellter Scharfrichter. Reichhart entstammte einer bayerischen Abdecker- und Scharfrichtersippe, die bis in die Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts zurückzuverfolgen ist. Sein Vater († 1902) besaß in der Einöde Wichenbach bei Tiefenthal eine kleine Landwirtschaft und arbeitete im Nebenerwerb als Wasenmeister. Johann besuchte die Volks- und die Feiertagsschule in Wörth an der Donau und schloss beide mit Erfolg ab. Er machte eine Lehre als Metzger. Scharfrichter in der Weimarer Republik Reichhart übernahm im April 1924 in Bayern das Amt des Scharfrichters von seinem Onkel Franz Xaver Reichhart (1851–1934). Bestellt vom bayerischen Justizministerium, wurde Reichart mit 150 Goldmark je Hinrichtung, zehn Mark Tagesspesen und kostenloser Eisenbahnfahrkarte 3. Klasse entlohnt. Bei Hinrichtungen in der Pfalz durfte er auch per Schnellzug anreisen. In den Jahren 1924 bis 1928 nahm die Anzahl der Hinrichtungen ab (im Jahr 1928 eine Hinrichtung). Reichhart hatte zunehmend Schwierigkeiten, den Lebensunterhalt seiner Familie zu bestreiten. Er erreichte, dass er zukünftig eine Nebentätigkeit – auch im Ausland – ausüben durfte und er von der Residenzpflicht entbunden wurde. Mangels Aufträgen gab er 1925 sein Fuhrwerkgeschäft auf, ebenso wie im darauffolgenden Jahr seine Gastwirtschaft am Mariahilfplatz. Danach verkaufte er als Handlungsreisender katholische Traktate in Oberbayern. 1928 wollte Reichhart seinen Vertrag mit dem Justizministerium lösen; dies gelang ihm nicht. Er verlegte seinen Wohnsitz nach Den Haag und war dort erfolgreich als selbständiger Gemüsehändler tätig. Im Frühjahr 1931 und im Juli 1932 reiste er nach München, um im Gefängnis Stadelheim je ein Todesurteil zu vollstrecken. -

I) Enhanced Interrogation (Torture

Secret Intelligence Service Room No. 15 Notes (I) Enhanced Interrogation (Torture) (C-IV) 28012017CIVR15tyxz Position : Overcome with intelligence, NOT via appeal to bestiality Table of Interrogation Techniques Apparently Recommended/Approved by U.S. Officials OK’d by Haynes Status Proposed Legal Approved Approved Proposed Approved 11/27/02; after by per by by Technique Category by Phifer by Hill Approved Rumsfeld’s Working Beaver Dunlavey Rumsfeld 10/11/02 10/25/02 by 1/15/03 Group 10/11/02 10/11/02 4/16/03 Rumsfeld Order 4/4/03 12/02/02 Direct, straightforward — — — — — — — Yes Yes questions Approved for Yelling at detainee I Yes Yes Yes Yes OK Yes Yes discretionary use Approved Deception: multiple for I Yes Yes Yes Yes OK Yes Yes interrogators discretionary use Deception: Approved Interrogator is from for country with discretionary reputation for I Yes Yes Yes Yes use OK Yes Yes harsh treatment of detainees; “False Flag” Incentive or removal of — — — — — — — Yes Yes, incentive Playing on a detainee’s love for — — — — — — — Yes Yes a particular group Playing on a detainee’s hate for — — — — — — — Yes Yes a particular group Significantly/ or moderately — — — — — — — Yes Yes increasing fear level of detainee Reducing fear level — — — — — — — Yes Yes of detainee Boosting the ego of — — — — — — — Yes Yes detainee Insulting the ego of detainee, not beyond the limits — — — — — — — Yes Yes that would apply to a POW Invoking feelings of — — — — — — — Yes Yes futility in detainee Convincing detainee — — — — — — — Yes Yes interrogator knows all