Leyland Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tucdirectory Trusted by Your Union

TUCDIRECTORY TRUSTED BY YOUR UNION best practice advice • returning officer statutory ballots • industrial action ballots turnout maximisation • independent scrutineer consultative ballots • data processing and capture secure print and fulfilment • results analysis artwork and design • membership profiling • e-voting e-distribution • branded voting websites digital engagement Contact us: 020 8365 8909 [email protected] @ERSvotes CONTENTS SECTION 1 SECTION 6 INTRODUCTION INTERNATIONAL Welcome 5 International affiliations 94 TUC structure 8 ITUC regional organisations 97 ITUC global union federations 98 SECTION 2 TUC PEOPLE SECTION 7 EXTERNAL CONTACTS Policy staff at Congress House 14 Policy staff in the regions 21 Campaigning, charity 102 and community SECTION 3 Employer and personnel 105 TUC SERVICES organisations Financial and other services 106 Information service 24 Government 106 Publishing 24 Industrial relations, workers’ 108 Websites 24 rights and union history TUC Aid 25 International, environment 109 Organising Academy 26 and anti-poverty Centres for the Unemployed 26 Legal 110 Trades Union Councils 27 Non-TUC unions and 111 TUC and young people 27 confederations Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum 29 Pensions 111 TUC Library Collections 29 Political 112 TUC archive 30 Research organisations 112 and public bodies SECTION 4 Skills and education 116 TRADE UNIONS Union statistics 32 SECTION 8 TUC member unions 41 CALENDAR 118 Confederations of unions 80 SECTION 5 UNIONLEARN AND TUC EDUCATION TUC Education 83 Learning through unions 88 1 SECTION ONE INTRODUCTION WELCOME 5 TUC STRUCTURE 8 WELCOME TO THE 2016 EDITION OF THE TUC DIRECTORY Every membership organisation offers a single, reliable, statistical resource for those who follow its fortunes, and for the TUC that is the Directory, our annual yearbook about our unions and TUC work. -

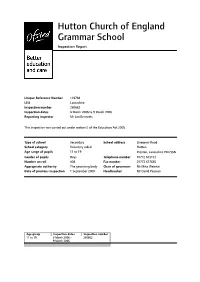

Inspection Report

Hutton Church of England Grammar School Inspection Report Unique Reference Number 119794 LEA Lancashire Inspection number 280662 Inspection dates 8 March 2006 to 9 March 2006 Reporting inspector Mr Jim Bennetts This inspection was carried out under section 5 of the Education Act 2005. Type of school Secondary School address Liverpool Road School category Voluntary aided Hutton Age range of pupils 11 to 19 Preston, Lancashire PR4 5SN Gender of pupils Boys Telephone number 01772 613112 Number on roll 804 Fax number 01772 617645 Appropriate authority The governing body Chair of governors Mr Mike Webster Date of previous inspection 1 September 2000 Headteacher Mr David Pearson Age group Inspection dates Inspection number 11 to 19 8 March 2006 - 280662 9 March 2006 Inspection Report: Hutton Church of England Grammar School, 8 March 2006 to 9 March 2006 © Crown copyright 2006 Website: www.ofsted.gov.uk This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that the information quoted is reproduced without adaptation and the source and date of publication are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the Education Act 2005, the school must provide a copy of this report free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Inspection Report: Hutton Church of England Grammar School, 8 March 2006 to 9 March 2006 1 Introduction The inspection was carried out by two of Her Majesty’s Inspectors and three additional inspectors. -

7494 the London Gazette, November 19, 1901

7494 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 19, 1901. about '.So chain east of the junction of Corporation - street, and terminating in . Bray-street with Tulketh-road. Fylde-road by a junction with Tramway Xramway No. 11, a double line 1-15 chains in No. 10 at a point about T42 chains north- length, being a connection between Tram- west of the junction therewith of Maudland- ..- waysNo. lOandNo. 17, hereinafter described, road. -.- commencing by a junction in Friargate with Tramway No. 19,1 mile 6 furlongs 2 50 chains Tramway No. 10 at a point about '15 in length, whereof 4 furlongs 4*50 chains -. chain north of the junction with Walker- will be double line and 1 mile 1 furlong street, thence along Friargate, and termina- 8'00 chains will be single, commencing by - ting in Friargate at a point about ]'30 . a junction with Tramway No. 8 in Mill - chains north of the said junction. Bank at a point about '40 chain south-west Tramway No. 12, 1 mile 3 furlongs 8'25 of the junction therewith of Deepdale-road, chains in length, whereof 2 furlongs proceeding thence along Blbbleton-lane, 1 chain will be double line and 1 mile and termina,ting at the boundary between 1 furlong 7'25 chains will be single line, the County Borough of Preston and the commencing in Water-lane by a junction Urban District of Fulwood, in Ribbleton- .with Tramway No. 10 at its termination, lane. and proceeding thence along Water-lane, Tramway No. 20,1 mile 0 furlong '60 chain - Tnlketh-road, Ashton Long-lane. -

Preston Bus Station

th July 2020 from 19 43 Preston Bus Station 43 Preston Railway Station Royal Cottom, Ancient Oak ane 44 yles L Preston Ho Hospital Cottom, Hoyles Lane e 44 Lan 43 Merrytrees Fulwood Wychnor Royal Preston Hospital mWay 44 Cotta Bampton Drive Terminus 44 Creswell Avenue L ea R oa W d oodp Plungingt l umpt o Tulk eth on R n R 44 Mill d Lane d d Preston Bus Station Ends pool R 43 Black Ingol, Cresswell Avenue Blackpool Road Cottom, Bampton Drive .co.ukLarches www.prestonbus Avenue 44 Ingol, Cresswell Avenue PrestonBusLtd Social icon Circle Only use blue and/or white. For more details check out our Preston Bus Station Brand Guidelines. @PrestonBus Preston 43 Bus Contact us: Station Preston Bus Ltd 221 Deepdale Road Preston PR1 6NY [email protected] Rotala Preston - Royal Preston Hospital 43 via Cottam Monday to Friday Ref.No.: 21P Commencing Date: 20/07/2020 Service No 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 Preston Bus Stn 0545 0615 0645 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 Preston Railway Station 0550 0620 0650 0720 0750 0820 0850 0920 0950 1020 1050 1120 Cottam Ancient Oak 0600 0630 0700 0730 0800 0830 0900 0930 1000 1030 1100 1130 Cottam Hoyles Ln 0608 0638 0708 0738 0808 0838 0908 0938 1008 1038 1108 1138 Fulwood Wychnor 0613 0643 0713 0743 0813 0843 0913 0943 1013 1043 1113 1143 Royal Preston Hospital 0623 0653 0723 0753 0823 0853 0923 0953 1023 1053 1123 1153 RotalaRotala Service No 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 Preston Bus Stn 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 1445 1515 1545 1615 1645 1720 Preston Railway Station 1150 -

5. Network Planning for Walking

Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan 5. Network Planning for Walking The future walking network has been derived through identifying those areas which would benefit from creating a sustainable link between trip origins and trip destinations within a reasonable walking distance of approximately 2km. Trip origins predominantly include densely populated residential areas and trip destinations include educational, employment and retail areas which are likely to attract a significant number of trips. As part of this process, funnel routes have been identified which incorporate the route which most pedestrians will follow to access a particular destination, however given the diverse nature of pedestrian movements, the routes do not extend into particular destinations since the route of each individual user will vary depending on their individual trip origin/end. In alignment with LCWIP guidance, Core Walking Zones have also been identified from identifying the area within each town which encompasses the greatest amount of trip attractors and therefore likely the generate the greatest levels of walking. The Four Core Walking Zones (CWZ) identified are: • Preston CWZ; • Lostock Hall CWZ; • Leyland CWZ; and • Chorley CWZ. 41 Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan 5.1 Proposed Walking Routes 5.1.1 Preston Core Walking Zone Figure 5-1 Preston CWZ / Funnel Routes The Preston CWZ proposals will improve facilities for both pedestrians and cyclists alike, making it safer and easier to access Preston inner city centre, UCLAN, Cardinal Newman College, and transport hubs such as Preston Railway and Bus Stations. Measures predominantly involve pedestrian priority / informal streets, to improve the safety and accessibility of the town centre for pedestrians. -

Press Release Wednesday 5 October 2016 Royal Court

PRESS RELEASE WEDNESDAY 5 OCTOBER 2016 ROYAL COURT THEATRE CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT: THE SEWING GROUP NANCY CRANE, FIONA GLASCOTT, JANE HAZLEGROVE, JOHN MACKAY, SARAH NILES and ALISON O’DONNELL cast in The Sewing Group by E V Crowe Nancy Crane, Fiona Glascott, Jane Hazlegrove, John Mackay, Sarah Niles and Alison O’Donnel have been cast in E V Crowe’s new play The Sewing Group which runs in the Royal Court Jerwood Theatre Upstairs Thursday 10 November – Thursday 22 December 2016 with press night 16 November. Directed and designed by Stewart Laing. With lighting design by Mike Brookes and sound design by Christopher Shutt. “I have spoken very clearly with her and I have told her that she is new here and that she must live how we live.” A woman arrives in a rural village in pre-industrial England. Her desire is to sew and learn from their simple way of life. But the group soon begins to suspect she is not who they thought she was. “There’s no point in just making quilts. They have to serve the village. They have to DO something.” E V Crowe (Playwright) For the Royal Court: Hero (part of the 2013 Olivier Award Winning Season at the Jerwood Theatre Upstairs), Kin (Shortlisted for Charles Wintour Most Promising Playwright Award) and One Runs the Other Doesn’t (Elephant and Castle). Other theatre includes: Brenda (Hightide/Yard), I Can Hear You (RSC), Liar Liar (Unicorn Theatre), Doris Day (Clean Break/Soho), Young Pretender (nabokov), ROTOR (Siobhan Davies Dance) Television includes: Glue, Big Girl. Radio includes: How to Say Goodbye Properly. -

Farington Hall Estate LANCASHIRE BUSINESS PARK PR26 6TZ

Farington Hall Estate LANCASHIRE BUSINESS PARK PR26 6TZ 38 ACRE SITE FOR SALE 38 ACRE SITE - FOR SALE AVAILABLE AS A WHOLE OR IN PLOTS FROM 1 ACRE, TO ACCOMMODATE INDUSTRIAL UNITS FROM 3,000 TO 200,000 SQ FT Location Farington Location Description Availability Hall The site is an established destination for businesses which enjoys a central location in Leyland, near Preston. Excellent transport links via the M6 national motorway network enable you to be in Preston in 10 Aerial Estate minutes and Manchester in 30 minutes. The site is centrally located in LANCASHIRE BUSINESS PARK Leyland and provides easy access to both junctions 28 and 29 of the Planning PR26 6TZ M6, junction 9 of the M61 and junction 1 of the M65 motorways. Situated in a prominent location the site offers excellent access to City Deal neighbouring towns including Preston and Chorley. Local shops and amenities are available in Leyland town centre. Further Information Click for maps Contact 38 ACRE SITE - FOR SALE 15 million 6.3 million 1.3 million people within a 120 min people within a 60 min people within a 30 min AVAILABLE AS A WHOLE drive time of the site drive time of the site drive time of the site OR IN PLOTS FROM 1 ACRE, TO ACCOMMODATE INDUSTRIAL UNITS FROM 3,000 TO 200,000 SQ FT Location Farington Maps Description Hall Availability Aerial Estate Lostock Hall LANCASHIRE BUSINESS PARK Planning PR26 6TZ Bamber Bridge City Deal A6 A582 Further Information M65 2 A582 1 A6 M65 Contact A5083 29 M61 32 A6 M55 1 M6 A59 FHE A6 8 Stanifield Centurion A49 PR26 6TZ B5256 31 -

Warburtons Families Collection No. 2

Warburtons Families Collection No. 2 Ray Warburton Last Updated: 3rd August 2014 Table of Contents A. .Family . from. Bury. .via . Cardiff. .(Ancestors . of. .Sam . .Warurton) . .1 . Descendants. of. John. Warburton. .3 . First. .Generation . .3 . Second. .Generation . .3 . Third. .Generation . .4 . Fourth. .Generation . .5 . Fifth. .Generation . .7 . The. .Ancestors . .of . .Markham . Jeremy. .Warburton . Warburton. .9 . Descendants. of. Richard. .Warburton . .10 . First. .Generation . .10 . Second. .Generation . .11 . Third. .Generation . .11 . A. .Reddish . Family. .13 . Descendants. of. Richard. .Warburton . .14 . First. .Generation . .14 . Second. .Generation . .15 . An. Early. Turton. .Family . .16 . Descendants. of. Thomas. .Warburton . .17 . First. .Generation . .17 . Second. .Generation . .17 . Third. .Generation . .17 . A. .Turton . .Family . .19 . Descendants. of. George. Warburton. .21 . First. .Generation . .21 . Second. .Generation . .21 . Third. .Generation . .22 . Fourth. .Generation . .23 . A. .Flintshire . .Family . .25 . Descendants. of. Joseph. .Warburton . .26 . First. .Generation . .26 . Second. .Generation . .26 . Third. .Generation . .27 . Produced by Legacy on 3 Aug 2014 Table of Contents . Fourth. .Generation . .27 . Name. Index. .29 . Produced by Legacy on. -

111 Piccadilly, Manchester, Greater Manchester

111 Piccadilly, Manchester, Greater Manchester View this office online at: https://www.newofficeeurope.com/details/serviced-offices-111-piccadilly-man chester-greater These fantastic serviced offices are well placed with terrific access to the major transport network adjacent to the Piccadilly railway station. After an intense and stylish refurbishment program the centre provides office accommodation of the very highest specification with spacious, contemporary offices and suites, a wonderful welcoming reception area with the whole place flooded by plenty of natural daylight. Offices start from 600 square feet to 4,000 square feet to suit many different business needs with flexible terms from a single year up to 25 years. This truly prestigious location and working environment can do wonders for your corporate image and your productivity. Transport links Nearest railway station: Manchester Piccadilly Nearest road: Nearest airport: Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Administrative support AV equipment Board room Car parking spaces Close to railway station Comfortable lounge Company signage Conference rooms Conference rooms Disabled facilities (DDA/ADA compliant) Double glazing Flexible contracts Furnished workspaces High-speed internet (dedicated) Kitchen facilities Lift Meeting rooms Modern interiors Office cleaning service On-site management support Open plan workstations Postal facilities/mail handling Reception staff Secure car parking Security system Staff on site 7 days a week Suspended Ceilings Telephone answering service Town centre location Unbranded offices WC (separate male & female) Wireless networking Location In an unrivaled city center location just a stones throw from Piccadilly railway and tram station and within a short walking distance from Piccadilly Gardens bus station. -

Manchester Visitor Information What to See and Do in Manchester

Manchester Visitor Information What to see and do in Manchester Manchester is a city waiting to be discovered There is more to Manchester than meets the eye; it’s a city just waiting to be discovered. From superb shopping areas and exciting nightlife to a vibrant history and contrasting vistas, Manchester really has everything. It is a modern city that is Throw into the mix an dynamic, welcoming and impressive range of galleries energetic with stunning and museums (the majority architecture, fascinating of which offer free entry) and museums, award winning visitors are guaranteed to be attractions and a burgeoning stimulated and invigorated. restaurant and bar scene. Manchester has a compact Manchester is a hot-bed of and accessible city centre. cultural activity. From the All areas are within walking thriving and dominant music distance, but if you want scene which gave birth to to save energy, hop onto sons as diverse as Oasis and the Metrolink tram or jump the Halle Orchestra; to one of aboard the free Mettroshuttle the many world class festivals bus. and the rich sporting heritage. We hope you have a wonderful visit. Manchester History Manchester has a unique history and heritage from its early beginnings as the Roman Fort of ‘Mamucium’ [meaning breast-shape hill], to today’s reinvented vibrant and cosmopolitan city. Known as ‘King Cotton’ or ‘Cottonopolis’ during the 19th century, Manchester played a unique part in changing the world for future generations. The cotton and textile industry turned Manchester into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Leaders of commerce, science and technology, like John Dalton and Richard Arkwright, helped create a vibrant and thriving economy. -

Part 3 of the Bibliography Catalogue

Bibliography - L&NWR Society Periodicals Part 3 - Railway Magazine Registered Charity - L&NWRSociety No. 1110210 Copyright LNWR Society 2012 Title Year Volume Page Railway Magazine Photos. Junction at Craven Arms Photos. Tyne-Mersey Power. Lime Street, Diggle 138 Why and Wherefore. Soho Road station 465 Recent Work by British Express Locomotives Inc. Photo. 2-4-0 No.419 Zillah 1897 01/07 20 Some Racing Runs and Trial Trips. 1. The Race to Edinburgh 1888 - The Last Day 1897 01/07 39 What Our Railways are Doing. Presentation to F.Harrison from Guards 1897 01/07 90 What Our Railways are Doing. Trains over 50 mph 1897 01/07 90 Pertinent Paragraphs. Jubilee of 'Cornwall' 1897 01/07 94 Engine Drivers and their Duties by C.J.Bowen Cooke. Describes Rugby with photos at the 1897 01/08 113 Photo.shed. 'Queen Empress' on corridor dining train 1897 01/08 133 Some Railway Myths. Inc The Bloomers, with photo and Precedent 1897 01/08 160 Petroleum Fuel for Locomotives. Inc 0-4-0WT photo. 1897 01/08 170 What The Railways are Doing. Services to Greenore. 1897 01/08 183 Pertinent Paragraphs. 'Jubilee' class 1897 01/08 187 Pertinent Paragraphs. List of 100 mile runs without a stop 1897 01/08 190 Interview Sir F.Harrison. Gen.Manager .Inc photos F.Harrison, Lord Stalbridge,F.Ree, 1897 01/09 193 TheR.Turnbull Euston Audit Office. J.Partington Chief of Audit Dept.LNW. Inc photos. 1897 01/09 245 24 Hours at a Railway Junction. Willesden (V.L.Whitchurch) 1897 01/09 263 What The Railways are Doing. -

A Walk Around St. Leonard's Parish Boundary, Penwortham

A Walk around St. Leonard’s Parish Boundary, Penwortham. Background. Penwortham is one of the ancient parishes of Lancashire. Until the 17th century it comprised of the townships of Longton, Howick, Penwortham, Farington and Hutton. In the early medieval period it also comprised of Brindle. The earliest written record of a church at Penwortham dates from the 1140’s. Map courtesy of Alan Crosby from his book “Penwortham in the past” Middleforth the township (which acquired it’s name from the middle ford on the River Ribble) was gradually growing in the early first part of the 19th century and the Vicar of St. Mary’s Rev. W.E. Rawstorne decided that the time was right to build a chapel school. Middleforth Chapel School opened in 1861 in the village, situated on the corner of Leyland Road and Marshall’s Brow. In 1901 a prefabricated iron church was built next to the school. This was in use until the present church was opened in 1970. As St. Leonard’s Church in Middleforth grew further, it was soon able to manage its own affairs and in 1959 became a conventional district but still in the Parish of St. Mary, Penwortham. Further growth took place with Penwortham becoming part of the Central Lancashire New Town. It was therefore decided that St. Leonard’s could stand alone from St. Mary’s and a new benefice of the Parish of St. Leonard, Penwortham was established on 1 April 1972 by an Order in Council dated 1 March 1972. The area concerned was taken out of the ancient parish of St.