Mount Robson – 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobility Statistics and Automated Hazard Mapping for Debris Flows and Rock Avalanches

Mobility Statistics and Automated Hazard Mapping for Debris Flows and Rock Avalanches Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5276 Version 1.1 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Mobility Statistics and Automated Hazard Mapping for Debris Flows and Rock Avalanches By Julia P. Griswold and Richard M. Iverson Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5276 Version 1.1 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 Revised 2014 This report and any updates to it are available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2007/5276/ For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Griswold, J.P., and Iverson, R.M., 2008, Mobility statistics and automated hazard mapping for debris flows and rock avalanches (ver. 1.1, April 2014): U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5276, 59 p. Manuscript approved for publication, December 12, 2007 Text edited by Tracey L. -

D3.1 – Technical Evaluation Report of Current Methods of Hazard Mapping of Debris Flows, Rock Avalanches, and Snow Avalanches

SIXTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME Project no. 018412 IRASMOS Integral Risk Management of Extremely Rapid Mass Movements Specific Targeted Research Project Priority VI: Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystems D3.1 – Technical evaluation report of current methods of hazard mapping of debris flows, rock avalanches, and snow avalanches Due date of deliverable: 31/05/2008 Actual submission date: 15/07/2008 Start date of project: 01/09/2005 Duration: 33 months WSL Swiss Federal Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research Revision [2] Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) SIXTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME PRIORITY VI Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystems SPECIFIC TARGETED RESEARCH PROJECT INTEGRAL RISK MANAGEMENT OF EXTREMELY RAPID MASS MOVEMENTS WORK PACKAGE 3: HAZARD ASSESSMENT AND MAPPING OF RAPID MASS MOVEMENTS DELIVERABLE D3.1 Hazard mapping of extremely rapid mass movements in Europe State of the art methods in practice Edited by: MASSIMILIANO BARBOLINI UNIVERSITY OF PAVIA OCTOBER 2007 SIXTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME PRIORITY VI - Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystems SPECIFIC TARGETED RESEARCH PROJECT “IRASMOS” Integral Risk Management of Extremely Rapid Mass Movements (contract -

Spring Ski-Ing in Wedge Pass

~ "~ Spring Ski-ing ~ "0 l:1 ~ .; ., ~ ~ in Wedge Pass ...0 .2 ., 0 :;; !::.'" '0 By W. A. Don Munday '8.. .." ...Il ., "THOSE things won't be much use here," ~ was the greeting our skis received when .. unloaded from the Paci.6c Great Eastern train '01) '0., at Alta Lake, B.C., the last week in April. ~ .... Wholly novel to local residents seemed the 0 idea of taking ski to the snow; at lake level, .Il 2,200 feet, snow lurked only in sheltered eIl" corners, for the winter's snowfall had been .tJ much less than normal. Bu t we knew the .9 driving clouds hid glacial peaks rising 5,000 to "e 7,000 feet above the lake. Although a few pairs of skis are owned around Alta Lake, the residents seem never to have discovered the real utility or joy of them. The lake is a beautiful still-unspoiled summer resort with possibilities as a winter resort. Our host was P. (Pip) H. G. Brock, the com fortable family cottage, "Primrose," being our headquarters. The third member of our party was Gilbert Hooley. The fourth, my wife, was due on the next semi-weekly train. Sproatt Mountain, rising directly for 4,800 feet from the lake, possesses a trail to a prospector's cabin near timberline, and Pip recommended this as a work-out. Scanty sun light and generous shadows marched across the morning sky. Half a mile from Primrose we passed the tragic site of the aeroplane crash which took the lives of both Pip's parents the previous summer while he was on a mountain trip with my wife and myself. -

Association of Clinical Pathologists

The Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists Number 163 July 2013 In this issue The Royal College of Pathologists Everything you wanted to know about your new Pathology: the science behind the cure consultant post but were afraid to ask Voice recognition in histopathology: pros and cons Public Engagement Innovation Grant Scheme www.rcpath.org/bulletin Subscribe to the Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists The College’s quarterly membership journal, the Bulletin, is the main means of communications between the College and its members, and between the members themselves. It features topical articles on the latest development in pathology, news from the College, as well as key events and information related to pathology. The Bulletin is delivered free of charge to all active College Members, retired Members who choose to receive mailings and Registered Trainees, and is published four times a year, in January, April, July and October. It is also available for our members to download on the College website at www.rcpath.org/bulletin The subscription rate for libraries and non-members is £100 per annum. To subscribe, contact the Publications Department on 020 7451 6730 or [email protected] Sign up today and keep up to date on what goes on in the world of pathology! The Royal College of Pathologists 2 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AF telephone 020 7451 6700 email [email protected] website www.rcpath.org President Dr Archie Prentice Vice Presidents Dr Bernie Croal Dr Suzy Lishman Professor Mike Wells Registrar Dr Rachael -

Leyland Historical Society

LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No. 1024919 PRESIDENT Mr. W. E. Waring CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Mr. P. Houghton Mrs. E. F. Shorrock HONORARY SECRETARY HONORARY TREASURER Mr. M. J. Park Mr. E. Almond Tel: (01772) 337258 AIMS To promote an interest in history generally and that of the Leyland area in particular MEETINGS Held on the first Monday of each month (September to July inclusive) at 7.30 pm in The Shield Room, Banqueting Suite, Civic Centre, West Paddock, Leyland SUBSCRIPTIONS Vice Presidents: £10.00 per annum Members: £10.00 per annum School Members: £1.00 per annum Casual Visitors: £3.00 per meeting A MEMBER OF THE LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE and THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR LOCAL HISTORY Visit the Leyland Historical Society's Web Site at: http//www.leylandhistoricalsociety.co.uk C O N T E N T S Page Title Contributor 4 Editorial Mary Longton 5 Society Affairs Peter Houghton 7 From a Red Letter Day to days with Red Letters Joan Langford 11 Fascinating finds at Haydock Park Edward Almond 15 The Leyland and Farington Mechanics’ Institution Derek Wilkins Joseph Farington: 3rd December 1747 to Joan Langford 19 30th December 1821 ‘We once owned a Brewery’ – W & R Wilkins of Derek Wilkins 26 Longton 34 More wanderings and musings into Memory Lane Sylvia Thompson Railway trip notes – Leyland to Manchester Peter Houghton 38 Piccadilly Can you help with the ‘Industrial Heritage of Editor 52 Leyland’ project? Lailand Chronicle No. 56 Editorial Welcome to the fifty-sixth edition of the Lailand Chronicle. -

Mount Robson Provincial Park, Draft Background Report

Mount Robson Provincial Park Including Mount Terry Fox & Rearguard Falls Provincial Parks DRAFT BACKGROUND REPORT September, 2006 Ministry of Environment Ministry of Environment BC Parks Omineca Region This page left blank intentionally Acknowledgements This Draft Background Report for Mount Robson Provincial Park was prepared to support the 2006/07 Management Plan review. The report was prepared by consultant Juri Peepre for Gail Ross, Regional Planner, BC Parks, Omineca Region. Additional revisions and edits were performed by consultant Leaf Thunderstorm and Keith J. Baric, A/Regional Planner, Omineca Region. The report incorporates material from several previous studies and plans including the Mount Robson Ecosystem Management Plan, Berg Lake Corridor Plan, Forest Health Strategy for Mount Robson Provincial Park, Rare and the Endangered Plant Assessment of Mount Robson Provincial Park with Management Interpretations, the Robson Valley Land and Resource Management Plan, and the BC Parks website. Park use statistics were provided by Stuart Walsh, Rick Rockwell and Robin Draper. Cover Photo: Berg Lake and the Berg Glacier (BC Parks). Mount Robson Provincial Park, Including Mount Terry Fox & Rearguard Falls Provincial Parks: DRAFT Background Report 2006 Table of Contents Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................1 Park Overview.................................................................................................................................................1 -

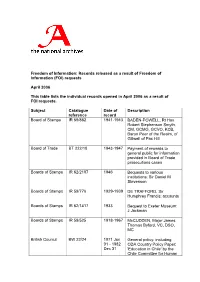

FOI) Requests

Freedom of Information: Records released as a result of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests April 2006 This table lists the individual records opened in April 2006 as a result of FOI requests. Subject Catalogue Date of Description reference record Board of Stamps IR 59/882 1941-1943 BADEN-POWELL, Rt Hon Robert Stephenson Smyth, CM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB, Baron Peer of the Realm, of Gillwell of Pax Hill Board of Trade BT 222/10 1943-1947 Payment of rewards to general public for information provided in Board of Trade prosecutions cases Boards of Stamps IR 62/2197 1946 Bequests to various institutions: Sir Daniel M Stevenson Boards of Stamps IR 59/776 1929-1939 DE TRAFFORD, Sir Humphrey Francis: accounts Boards of Stamps IR 62/1417 1933 Bequest to Exeter Museum: J Jackman Boards of Stamps IR 59/525 1918-1967 McCUDDEN, Major James Thomas Byford, VC, DSO, MC British Council BW 22/24 1971 Jan General policy: including 01 - 1982 ODA Country Policy Paper; Dec 31 'Education in Chile' by the Chile Committee for Human Rights Courts Martial WO 71/1105 1945 Harpley, DA Offence: Rape Courts Martial AIR 18/50 1966 Feb Sgt Kelly, A B. Offence: 21 Murder. (Conviction later quashed) Crime HO 1922 CRIMINAL CASES: 144/1754/425994 ARMSTRONG, Herbert Rowse Convicted at Hereford on 13 April 1922 for murder and sentenced to death Crime HO 144/22540 1926-1946 CRIMINAL: Michael Dennis Corrigan alias Edward Kettering alias Kenneth Edward Cassidy: confidence trickster. Crime HO 144/14913 1931 CRIMINAL: Unsolved murder of Louisa Maud Steele at Blackheath: alleged confession by Arthur James Faraday Salvage, murderer of Ivy Godden. -

Jasper National Park Mountain Biking Guide 2013

RIDE A MOUNTAIN PLAN AHEAD AND PREPARE JASPER NATIONAL PARK Cruisy, cross-country fun... Mountain Biking Guide In most places, ‘Mountain Biking’ either means one of two things; finding some dirt next to the sidewalk to ride on, or expert level downhill riding. However, if you bike in Jasper, you get that rare third option; cruisy, Photo: N. Gaboury N. Photo: cross-country fun. Gaboury N. Photo: Darren Langley Photo: While most of the trails described are fun, flowing, valley bottom trails, Jasper does have some Remember, you are responsible for your own safety. - Photo: N. Gaboury N. - Photo: Jasper has what might be the best trail great climbing for riders looking for physical challenges and eye-popping alpine scenery. • Always wear a helmet and safety gear. Know your equipment. system in the world. Ask any cyclist why they • Get advice at a Parks Canada Information Centre, including 16a trail conditions, descriptions and weather. P 7 Palisades Lookout Overlander Trail come back to Jasper, and you’ll likely hear 100 12 (MAP A & D) Distance: 11 km one way Elevation gain: 840 m P Signal Mountain • Pack adequate water, food, gear, maps, first aid. Carry bear (MAP A ) Distance: 9.1 km one way Elevation gain: 925 m spray and know how to use it. that it’s because the park’s well-connected, Hardy riders who persevere up the long, steep climb are • Tell someone where you are going and when you are rewarded with panoramic views of the Athabasca River Valley Single speed bikers, beware! This sustained uphill requires expected back. -

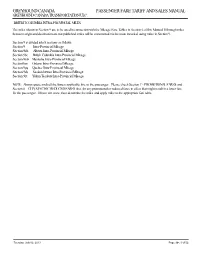

British Columbia Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. BRITISH COLUMBIA INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9bc.1 of 52 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. BRITISH COLUMBIA INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBOTSFORD BC AND BETWEEN ABBOTSFORD BC AND BETWEEN ABBOTSFORD BC AND ALLISON PASS BC 87 GREENWOOD BC 308 OLIVER BC 235 ARMSTRONG BC 251 HEDLEY BC 160 ONE HUNDRED MILE -

The Executioner at War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors

The Executioner At War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors lbert Pierrepoint was not called up when war broke out. But there were war-related changes for him as well. Not only murderers and A murderesses could now be punished by death, there were sentences under the Treason Act and Treachery Act as well, both imposing »death« as the maximum penalty. The Treason Act went back to an ancient law of King Edward III's time (1351). »Treason« was, first of all, any attack on the legitimate ruler, for instance by planning to murder him, or on the legitimacy of the succession to the throne: It was treason as well if someone tried to smuggle his genes into the royal family by adultery with the queen, the oldest daughter of the king or the crown prince’s wife. This aspect of the law became surprisingly topical in our days: When it became known that Princess Diana while married to the Prince of Wales had had an affair with her riding instructor James Hewitt, there were quite some law experts who declared this to be a case of treason – following the letter of the Act, it doubtlessly was. However as it would have been difficult to find the two witnesses prescribed by the Act, a prosecution was never started. Just Hewitt’s brother officers of the Household Cavalry did something: They »entered his name on the gate« which was equivalent to drumming him out of the regiment and declaring the barracks off limits for him.317 During World War II, it became important that a person committed treason if they supported the king’s enemies in times of war. -

Albert Pierrepoint and the Cultural Persona of the Twentieth- Century Hangman

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Sussex Research Online Albert Pierrepoint and the cultural persona of the twentieth- century hangman Article (Accepted Version) Seal, Lizzie (2016) Albert Pierrepoint and the cultural persona of the twentieth-century hangman. Crime, Media, Culture, 12 (1). pp. 83-100. ISSN 1741-6590 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/60124/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Introduction Despite his symbolic importance, the figure of the English hangman remains largely ignored by scholars.1 In an article dating from the mid-s, ‘oi : oted that it is supisig that geate attetio has ot ee dieted to the eeutioe ad this oseatio eais petiet. -

Prepared For

Terasen Pipelines (Trans Mountain) Inc. •••DRAFT••• Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat TMX - Anchor Loop Project November 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The TERA/Westland staff and subconsultants responsible for the TMX - Anchor Loop Project Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat Program gratefully acknowledge the assistance and cooperation of Parks Canada and BC Parks management. Specifically we want to thank the following field and administrative staff: Jasper National Park Environment Canada • Thea Mitchell • Dale Kirkland • Wes Bradford • Paul Gregoire • Geoff Skinner • Andrew Robinson • Ward Hughson • Deanne Newkirk • Mark Bradley • Kim Forster BC Ministry of Environment • Anne Forshner • Chris Ritchie • Brenda Shepherd • Ted Zimmerman • Jesse Whittington Alberta Sustainable Resource Development BC Parks • Gordon Stenhouse • Rick Rockwell • Margo Pybus • Wayne Van Velzen • Jeff Kneteman • Hugo Mulyk • Rhonda Thibeault • Donna Thornton The help and support of Simpcw First Nation field assistants Sidney Jules, Steve Jules and Colin Eustache is also acknowledged. The Simpcw field personnel enthusiastically participated in all phases of the wildlife program. We thank them for their hard work and interest in this program. Several environmental nongovernment organizations took an active role in the identification of wildlife Valued Ecosystem Components and other aspects of program planning. We appreciate their guidance and cooperation throughout the course of the wildlife program work. Terasen Pipelines (Trans Mountain) Inc. •••DRAFT••• Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat TMX - Anchor Loop Project November 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The TMX - Anchor Loop Project proposed by Terasen Pipelines (Trans Mountain) Inc. involves the construction of 158 km of 812 mm or 914 mm (32-inch or 36-inch) diameter oil pipeline loop from a location west of Hinton, Alberta, across Jasper National Park (JNP) to a location immediately west of Mount Robson Provincial Park (MRPP), near Rearguard, British Columbia (BC).