From the Bilingual to the Monolingual Dictionary Gabriele Stein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) Services Individualized Modifications/Accommodations Plan

Student Name/ESOL Level:_____ __________ _ _ _ _ _ _ School/Grade Level: _____________________ | 1 School District of _____________________________________ County English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) Services Individualized Modifications/Accommodations Plan General Specific Strategies and Ideas Modifications General Collaborate closely with ESOL teacher. Establish a safe/relaxed/supportive learning environment. Review previously learned concepts regularly and connect to new learning. Contextualize all instruction. Utilize cooperative learning. Teach study, organization, and note taking skills. Use manuscript (print) fonts. Teach to all modalities. Incorporate student culture (as appropriate). Activate prior knowledge. Allow extended time for completion of assignments and projects. Rephrase directions and questions. Simplify language. (Ex. Use short sentences, eliminate extraneous information, convert narratives to lists, underline key words/key points, use charts and diagrams, change pronouns to nouns). Use physical activity. (Total Physical Response) Incorporate students L1 when possible. Develop classroom library to include multicultural selections of all reading levels; especially books exemplifying students’ cultures. Articulate clearly, pause often, limit idiomatic expressions, and slang. Permit student errors in spelling and grammar except when explicitly taught. Acknowledge errors as indications of learning. Allow frequent breaks. Provide preferential seating. Model expected student outcomes. Prioritize course objectives. Reading Pre-teach vocabulary. in the Content Areas Teach sight vocabulary for beginning English readers. Allow extended time. Shorten reading selections. Choose alternate reading selections. Allow in-class time for free voluntary and required reading. Use graphic novels/books and illustrated novels. Leveled readers Modified text Use teacher read-alouds. Incorporate gestures/drama. Experiment with choral reading, duet (buddy) reading, and popcorn reading. -

Four Strands to Language Learning

International Journal of Innovation in English Language Teaching… ISSN: 2156-5716 Volume 1, Number 2 © 2012 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. APPLYING THE FOUR STRANDS TO LANGUAGE LEARNING Paul Nation1 and Azusa Yamamoto2 Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand1 and Temple University Japan2 ABSTRACT The principle of the four strands says that a well balanced language course should have four equal strands of meaning focused input, meaning focused output, language focused learning, and fluency development. By applying this principle, it is possible to answer questions like How can I teach vocabulary? What should a well balanced listening course contain? How much extensive reading should we do? Is it worthwhile doing grammar translation? and How can I find out if I have a well balanced conversation course? The article describes the rationale behind such answers. The four strands principle is primarily a way of providing a balance of learning opportunities, and the article shows how this can be done in self regulated foreign language learning without a teacher. Keywords: Fluency learning, four strands, language focused learning, meaning focused input, meaning focused output. INTRODUCTION The principle of the four strands (Nation, 2007) states that a well balanced language course should consist of four equal strands – meaning focused input, meaning focused output, language focused learning, and fluency development. Each strand should receive a roughly equal amount of time in a course. The meaning focused input strand involves learning through listening and reading. This is largely incidental learning because the learners’ attention should be focused on comprehending what is being read or listened to. The meaning focused output strand involves learning through speaking and writing and in common with the meaning focused input strand involves largely incidental learning. -

Bilingual Dictionary Generation for Low-Resourced Language Pairs

Bilingual dictionary generation for low-resourced language pairs Varga István Yokoyama Shoichi Yamagata University, Yamagata University, Graduate School of Science and Engineering Graduate School of Science and Engineering [email protected] [email protected] choice and adaptation of the translation method Abstract to the problem of available translation resources between the chosen languages. Bilingual dictionaries are vital resources in One possible solution is bilingual corpus ac- many areas of natural language processing. quisition for statistical machine translation Numerous methods of machine translation re- (SMT). However, for highly accurate SMT sys- quire bilingual dictionaries with large cover- tems large bilingual corpora are required, which age, but less-frequent language pairs rarely are rarely available for less represented lan- have any digitalized resources. Since the need for these resources is increasing, but the hu- guages. Rule or sentence pattern based systems man resources are scarce for less represented are an attractive alternative, for these systems the languages, efficient automatized methods are need for a bilingual dictionary is essential. needed. This paper introduces a fully auto- Our paper targets bilingual dictionary genera- mated, robust pivot language based bilingual tion, a resource which can be used within the dictionary generation method that uses the frameworks of a rule or pattern based machine WordNet of the pivot language to build a new translation system. Our goal is to provide a low- bilingual dictionary. We propose the usage of cost, robust and accurate dictionary generation WordNet in order to increase accuracy; we method. Low cost and robustness are essential in also introduce a bidirectional selection method order to be re-implementable with any arbitrary with a flexible threshold to maximize recall. -

Teaching and Learning Academic Vocabulary

Musa Nushi Shahid Beheshti University Homa Jenabzadeh Shahid Beheshti University Teaching and Learning Academic Vocabulary Developing learners' lexical competence through vocabulary instruction has always been high on second language teachers' agenda. This paper will be focusing on the importance of academic vocabulary and how to teach such vocabulary to adult EFL/ESL learners at intermediate and higher levels of proficiency in the English language. It will also introduce several techniques, mostly those that engage students’ cognitive abilities, which can in turn facilitate the process of teaching and learning academic vocabulary. Several online tools that can assist academic vocabulary teaching and learning will also be introduced. The paper concludes with the introduction and discussion of four important academic vocabulary word lists which can help second language teachers with the identification and selection of academic vocabulary in their instructional planning. Keywords: Vocabulary, Academic, Second language, Word lists, Instruction. 1. Introduction Vocabulary is essential to conveying meaning in a second language (L2). Schmitt (2010) notes that L2 learners seem cognizant of the importance of vocabulary in language learning, as evidenced by their tendency to carry dictionaries, and not grammar books, around with them. It has even been suggested that the main difference between intermediate and advanced L2 learners lies not in how complex their grammatical knowledge is but in how expanded and developed their mental lexicon is (Lewis, 1997). Similarly, McCarthy (1990) observes that "no matter how well the student learns grammar, no matter how successfully the sounds of L2 are mastered, without words to express a wide range of meanings, communication in an L2 just cannot happen in any meaningful way" (p. -

Defining Vocabulary Words Grades

Vocabulary Instruction Booster Session 2: Defining Vocabulary Words Grades 5–8 Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin © 2014 Texas Education Agency/The University of Texas System Acknowledgments Vocabulary Instruction Booster Session 2: Defining Vocabulary Words was developed with funding from the Texas Education Agency and the support and talent of many individuals whose names do not appear here, but whose hard work and ideas are represented throughout. These individuals include national and state reading experts; researchers; and those who work for the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Education Agency. Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts College of Education The University of Texas at Austin www.meadowscenter.org/vgc Manuel J. Justiz, Dean Greg Roberts, Director Texas Education Agency Michael L. Williams, Commissioner of Education Monica Martinez, Associate Commissioner, Standards and Programs Development Team Meghan Coleman, Lead Author Phil Capin Karla Estrada David Osman Jennifer B. Schnakenberg Jacob Williams Design and Editing Matthew Slater, Editor Carlos Treviño, Designer Special thanks to Alice Independent School District in Alice, Texas Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin © 2014 Texas Education Agency/The University of Texas System Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin © 2014 Texas Education Agency/The University of Texas System Introduction Explicit and robust vocabulary instruction can make a significant difference when we are purposeful in the words we choose to teach our students. -

The Impact of Using a Bilingual Dictionary (English-Arabic) for Reading and Writing in a Saudi High School

THE IMPACT OF USING A BILINGUAL DICTIONARY (ENGLISH-ARABIC) FOR READING AND WRITING IN A SAUDI HIGH SCHOOL By Ali Almaliki A Master’s Thesis/Project Capstone Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Education Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Department of Language, Learning and leadership State University of New York at Fredonia Fredonia, New York December 2017 THE IMPACT OF USING A BILINGUAL DICTIONARY (ENGLISH-ARABIC) FOR READING AND WRITING IN A SAUDI HIGH SCHOOL ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to explore the impact of using a bilingual dictionary (English- Arabic) for reading and writing in a Saudi high school and also to explore the Saudi Arabian students’ attitudes and EFL teachers’ perceptions toward the use of bilingual dictionaries. This study involves 65 EFL students and 5 EFL teachers in one Saudi high school in the city of Alkobar. Mixed methods research is used in which both qualitative and quantitative data are collected. For participating students, pre-test, post-test, and surveys are used to collect quantitative data. For participating teachers and students, in-person interviews are conducted with select teachers and students so as to collect qualitative data. This study has produced eight findings; first is that the use of a bilingual dictionary has a significant effect on the reading and writing scores for both high and low proficiency EFL students. Other findings include that most EFL students feel that using a bilingual dictionary in EFL classrooms is very important to help them translate and learn new vocabulary words but their use of a bilingual dictionary is limited by the strategies for use that students know or are taught, and that both invoice and experienced EFL teachers agree that the use of a bilingual dictionary is important for learning word meaning and vocabulary, but they do not all agree about which grades should use bilingual dictionaries. -

Dictionaries in the ESL Classroom

7/22/2009 The need for dictionaries in the ESL classroom: Dictionaries empower students by making them responsible for their own learning. Once students are able to use a dictionary well, they are self-sufficient in Dictionaries: finding the information on their own. Use and Function in the ESL Dictionaries present a very useful tool in the ESL classroom. However, teachers need to EXPLICITLY teach students skills so that they can be Classroom utilized to maximum extent. Dictionary use can enhance vocabulary acquisition and comprehension. If the dictionary is sufficiently current, and idiomatic colloquialisms are included, the student can [also] see representations of contemporary culture as seen through language. Why teachers need to explicitly teach dictionary skills: “If we do not teach students how to use the dictionary, it is unlikely that they will demand that they be taught, since, while teachers do not believe that students have adequate dictionary skills, students believe that they do” (Bilash, Gregoret & Loewen, 1999, p.4). Dictionary use skills: Dictionaries are not self explanatory; directions need to be made clear so that students can disentangle information, and select the appropriate meaning for the task at hand. Students need to learn how a dictionary works, how a dictionary or reference resource can help them, and also how to become aware of what they need and what kind of dictionary will best respond to their needs. Teachers need to firstly make sure that students are acquainted and familiar with the alphabet and its order. Secondly, teachers need to orientate students as to what a dictionary As students become more familiar and comfortable with basic dictionary entails, its functions, and relative terminology. -

Aspects of Idiom*

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Calgary (Working) Papers in Linguistics Volume 07, Winter 1982 1982-01 Aspects of idiom* Sayers, Coral University of Calgary Sayers, C. (1982). Aspects of idiom*. Calgary Working Papers in Linguistics, 7(Winter), 13-32. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51297 journal article Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Aspects of Idiom* Coral Sayers • 1. Introduction Weinreich (1969) defines an idiom as "a complex expression • whose meaning cannot be derived from the meanings of its elements." This writer has collected examples of idioms from the English, German, Australian English, and Quebec French dialects (Appendix I) in order to examine the properties of the idiom, to explore in the literature the current concepts of idiom, and to relate relevant knowledge gained by these processes to the teaching of English as a Second Language. An idiom may be a word, a "lexical idiom," or, if it has a more complicated constituent structure, a "phrasal idiom." (Katz and Postal, 1964, cited by Fraser, 1970:23) As the lexical idiom, domi nated by a single branch syntactic category (e.g. "squatter," a noun) does not present as much difficulty as does the phrasal idiom, this paper will focus upon the latter. Despite the difficulties presented by idioms to the Trans formational Grammar model, e.g. the contradiction of the claim that virtually all sentences have a low occurrence probability and frequency (Coulmas, 1979), the consensus of opinion seems to be that idioms can be accommodated in the grammatical description. Phrasal idioms of English should be considered as a "more complicated variety of mono morphemic lexical entries." (Fraser, 1970:41) 2. -

Bilingual Word-To-Word Glossaries List: for Use with the M-STEP and MI-Access Assessments

Bilingual Word-to-Word Glossaries List: For use with the M-STEP and MI-Access Assessments List of Bilingual Word-to-Word Dictionaries and Glossaries The Office of Standards & Assessment (OSA) approves the following bilingual dictionaries and glossaries for use on Michigan Test of Educational Progress (M-STEP) and MI-Access tests (Available as appropriate, see Michigan’s Accommodations Manual). More specifically, word-to- word bilingual dictionaries may be used with the M-STEP and MI-Access Assessments only. Please note that the use of dictionaries of any kind is prohibited on the WIDA assessments: W-APT, ACCESS for ELLs, and Alternate ACCESS for ELLs. Educators should refer to the OSA accessibility tables and guidance for more information on this type of support. These word-to-word bilingual dictionaries can be used by students who are currently reported as English learners (ELs) or who have been reported as ELs in prior years and may still need this support from time-to-time in the classroom. The bilingual dictionaries and glossaries listed in this publication are limited to those that provide word-to-word translations only. A list of distributors appears at the end of this publication. This is not an exhaustive list of available bilingual word-to- word dictionaries, but is intended to aid districts in their selection process and ensuring that students who may need this support for the classroom and assessment have access to it. Additionally, students who may use electronic word-to-word dictionaries in the classroom must use a paper based version for Michigan’s assessments. -

SELECTING and CREATING a WORD LIST for ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING by Deny A

Teaching English with Technology, 17(1), 60-72, http://www.tewtjournal.org 60 SELECTING AND CREATING A WORD LIST FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING by Deny A. Kwary and Jurianto Universitas Airlangga Dharmawangsa Dalam Selatan, Surabaya 60286, Indonesia d.a.kwary @ unair.ac.id / [email protected] Abstract Since the introduction of the General Service List (GSL) in 1953, a number of studies have confirmed the significant role of a word list, particularly GSL, in helping ESL students learn English. Given the recent development in technology, several researchers have created word lists, each of them claims to provide a better coverage of a text and a significant role in helping students learn English. This article aims at analyzing the claims made by the existing word lists and proposing a method for selecting words and a creating a word list. The result of this study shows that there are differences in the coverage of the word lists due to the difference in the corpora and the source text analysed. This article also suggests that we should create our own word list, which is both personalized and comprehensive. This means that the word list is not just a list of words. The word list needs to be accompanied with the senses and the patterns of the words, in order to really help ESL students learn English. Keywords: English; GSL; NGSL; vocabulary; word list 1. Introduction A word list has been noted as an essential resource for language teaching, especially for second language teaching. The main purpose for the creation of a word list is to determine the words that the learners need to know, in order to provide more focused learning materials. -

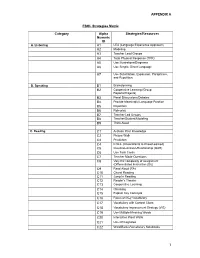

APPENDIX a ESOL Strategies Matrix Category Alpha Numeric ID

APPENDIX A ESOL Strategies Matrix Category Alpha Strategies/Resources Numeric ID A. Listening A1 LEA (Language Experience Approach) A2 Modeling A3 Teacher Lead Groups A4 Total Physical Response (TPR) A5 Use Illustrations/Diagrams A6 Use Simple, Direct Language A7 Use Substitution, Expansion, Paraphrase, and Repetition. B. Speaking B1 Brainstorming B2 Cooperative Learning (Group Reports/Projects) B3 Panel Discussions/Debates B4 Provide Meaningful Language Practice B5 Repetition B6 Role-play B7 Teacher-Led Groups B8 Teacher/Student/Modeling B9 Think Aloud C. Reading C1 Activate Prior Knowledge C2 Picture Walk C3 Prediction C4 K-W-L (Know/Wants to Know/Learned) C5 Question-Answer-Relationship (QAR) C6 Use Task Cards C7 Teacher Made Questions C8 Vary the complexity of assignment (Differentiated Instruction (DI)) C9 Read Aloud (RA) C10 Choral Reading C11 Jump In Reading C12 Reader’s Theater C13 Cooperative Learning C14 Chunking C15 Explain Key Concepts C16 Focus on Key Vocabulary C17 Vocabulary with Context Clues C18 Vocabulary Improvement Strategy (VIS) C19 Use Multiple Meaning Words C20 Interactive Word Walls C21 Use Of Cognates C22 Word Banks/Vocabulary Notebooks 1 APPENDIX A C23 Decoding/Phonics/Spelling C24 Unscramble: Sentences/Words C25 Graphic Organizers C26 Semantic Mapping C27 Timelines C28 Praise-Question-Polish (PQP) C29 Visualization C30 Reciprocal Teaching C31 Context Clues C32 Verbal Clues/Pictures C33 Schema Stories C34 Captioning C35 Venn Diagrams C36 Story Maps C37 Structural Analysis C38 Reading for a Specific Purpose C39 Pantomimes/Dramatization C40 Interview C41 Retelling C42 Think/Pair/Share C43 Dictation C44 Cloze Procedures C45 Graphic Representations C46 Student Self Assessment C47 Flexible Grouping C48 Observation/Anecdotal C49 Portfolios C50 Wordless/Picture Books C51 Highlighting Text C52 Note-Taking/ Outline Notes C53 Survey/Question/Read/Recite/Review (SQ3R) C54 Summarizing C55 Buddy/Partner Reading C56 Collaborative Groups C57 Pacing of Lessons C58 Exit Slips C59 Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) D. -

An Analysis of the Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary^ Second Edition

An Analysis of the Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary^ Second Edition Takahiro Kokawa Y ukiyoshi Asada JUNKO SUGIMOTO TETSUO OSADA Kazuo Iked a 1. Introduction The year 2016 saw the publication of the revised Second Edition of the Merriam-Webster^ Advanced Learner }s English Dictionary (henceforth MWALED2)y after the eight year interval since the first edition was put on the market in 2008. We would like to discuss in this paper how it has, or has not changed through nearly a decade of updating between the two publications. In fact,when we saw the striking indigo color on the new edition ’s front and back covers, which happens to be prevalent among many EFL dictionaries on the market nowadays, yet totally different from the emerald green appearance of the previous edition, MWALED1, we anticipated rather extensive renovations in terms of lexicographic fea tures, ways of presentation and the descriptions themselves, as well as the extensiveness of information presented in MWALED2. However, when we compare the facts and figures presented in the blurbs of both editions, we find little difference between the two versions —‘more than 160,000 example sentences ,’ ‘100,000 words and phrases with definitions that are easy to understand/ ‘3,000 core vocabulary words ,’ ’32,000 IPA pronunciations ,,‘More than 22,000 idioms, verbal collocations, and commonly used phrases from Ameri can and British English/ (More than 12,000 usage labels, notes, and paragraphs’ and 'Original drawings and full-color art aid understand ing [sic]5 are the common claims by the two editions.