Popular Music Stuart Bailie a Troubles Archive Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968)

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Carney, “With Electric Breath” “With Electric Breath”: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968) Court Carney In 1956, police in New Jersey apprehended Woody Guthrie on the presumption of vagrancy. Then in his mid-40s, Guthrie would spend the next (and last) eleven years of his life in various hospitals: Greystone Park in New Jersey, Brooklyn State Hospital, and, finally, the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, where he died. Woody suffered since the late 1940s when the symptoms of Huntington’s disease first appeared—symptoms that were often confused with alcoholism or mental instability. As Guthrie disappeared from public view in the late 1950s, 1,300 miles away, Bob Dylan was in Hibbing, Minnesota, learning to play doo-wop and Little Richard covers. 1 Young Dylan was about to have his career path illuminated after attending one of Buddy Holly’s final shows. By the time Dylan reached New York in 1961, heavily under the influence of Woody’s music, Guthrie had been hospitalized for almost five years and with his motor skills greatly deteriorated. This meeting between the still stylistically unformed Dylan and Woody—far removed from his 1940s heyday—had the makings of myth, regardless of the blurred details. Whatever transpired between them, the pilgrimage to Woody transfixed Dylan, and the young Minnesotan would go on to model his early career on the elder songwriter’s legacy. More than any other of Woody’s acolytes, Dylan grasped the totality of Guthrie’s vision. Beyond mimicry (and Dylan carefully emulated Woody’s accent, mannerisms, and poses), Dylan almost preternaturally understood the larger implication of Guthrie in ways that eluded other singers and writers at the time.2 As his career took off, however, Dylan began to slough off the more obvious Guthrieisms as he moved towards his electric-charged poetry of 1965-1966. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

Press Book from 01.10.2014 to 31.10.2014

Press Book from 01.10.2014 to 31.10.2014 Copyright Material. This may only be copied under the terms of a Newspaper Licensing Ireland agreement (www.newspaperlicensing.ie) or written publisher permission. -2- Table of Contents 29/10/2014 Irish Examiner: €33.8m royalties bonanza for artists............................................................................................ 3 16/10/2014 Tralee Outlook: DEADLINE LOOMS TO ENTER 2014 CHRISTIE HENNESSY SONG CONTEST..................................... 4 18/10/2014 Nenagh Guardian: DEADLINE LOOMS TO ENTER CHRISTIE HENNESSY SONG CONTEST..............................................5 11/10/2014 Limerick Leader Saturday County-Leader 2: Dolan's book the dream ticket to mark 20 year celebrations.........................................................6 11/10/2014 Limerick Leader Sat City-Leader 2: Dolan's book the dream ticket to mark 20 year celebrations.........................................................8 11/10/2014 Limerick Leader West Edition - Leader 2: Dolan's book the dream ticket to mark 20 year celebrations.........................................................9 29/10/2014 Irish Independent Tabloid: IMRO artists' royalties bonanza tops €33.8m..............................................................................10 09/10/2014 Athlone Advertiser: IMRO launches new awards........................................................................................................ 11 02/10/2014 Westmeath Topic: 'MULUNGAR'S CAVERN CLUB' TO CLOSE..................................................................................... -

BBC Music Booklet Celebrating 80 Years of Music.Pdf

Celebrating Years of Music A Serenade to Music “We are the music-makers And we are the dreamers of dreams…” (Arthur William Edgar O’Shaughnessy, Ode) The story of BBC Northern Ireland’s involvement in nurturing and broadcasting local musical talent is still in the making. This exhibition provides a revealing glimpse of work in progress at the BBC’s Community Archive in documenting the programmes and personalities who have brought music in all its different forms to life, and looks at how today’s broadcasters are responding to the musical styles and opportunities of a new century. It celebrates BBC NI’s role in supporting musical diversity and creative excellence and reflects changes in fashion, technology and society across 80 years of local broadcasting. “ Let us celebrate the way we were and the way we live now. Much has been achieved since 2BE’s first faltering (and scarcely heard) musical broadcast in 1924. Innovation has Let us celebrate the ways we will be... been a defining feature of every decade from early radio concerts in regional towns and country halls to the pioneering work of Sean O’Boyle in recording traditional music and Sam Hanna Bell’s 1950s programmes of Belfast’s Let us count the ways to celebrate. street songs.The broadcasts of the BBC Wireless Orchestra and its successors find their contemporary echo in the world-class performances of the Ulster Orchestra and BBC NI’s radio and television schedules continue to Let us celebrate.” reverberate to the diverse sounds of local jazz, traditional and country music, religious services, brass bands, choirs, (Roger McGough - Poems of Celebration) contemporary rock, pop and dance music. -

Glastonburyminiguide.Pdf

GLASTONBURY 2003 MAP Produced by Guardian Development Cover illustrations: John & Wendy Map data: Simmons Aerofilms MAP MARKET AREA INTRODUCTION GETA LOAD OF THIS... Welcome to Glastonbury 2003 and to the official Glastonbury Festival Mini-Guide. This special edition of the Guardian’s weekly TV and entertainments listings magazine contains all the information you need for a successful and stress-free festival. The Mini-Guide contains comprehensive listings for all the main stages, plus the pick of the acts at Green Fields, Lost and Cabaret Stages, and advice on where to find the best of the weird and wonderful happenings throughout the festival. There are also tips on the bands you shouldn’t miss, a rundown of the many bars dotted around the site, fold-out maps to help you get to grips with the 600 acres of space, and practical advice on everything from lost property to keeping healthy. Additional free copies of this Mini-Guide can be picked up from the Guardian newsstand in the market, the festival information points or the Workers Beer Co bars. To help you keep in touch with all the news from Glastonbury and beyond, the Guardian and Observer are being sold by vendors and from the newsstands at a specially discounted price during the festival . Whatever you want from Glastonbury, we hope this Mini-Guide will help you make the most of it. Have a great festival. Watt Andy Illustration: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INFORMATION POINTS hygiene. Make sure you wash MONEY give a description. If you lose There are five information your hands after going to the loo The NatWest bank is near the your children, ask for advice points where you can get local, and before eating. -

Festival 30000 LP SERIES 1961-1989

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS FESTIVAL 30,000 LP SERIES 1961-1989 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER AUGUST 2020 Festival 30,000 LP series FESTIVAL LP LABEL ABBREVIATIONS, 1961 TO 1973 AML, SAML, SML, SAM A&M SINL INFINITY SODL A&M - ODE SITFL INTERFUSION SASL A&M - SUSSEX SIVL INVICTUS SARL AMARET SIL ISLAND ML, SML AMPAR, ABC PARAMOUNT, KL KOMMOTION GRAND AWARD LL LEEDON SAT, SATAL ATA SLHL LEE HAZLEWOOD INTERNATIONAL AL, SAL ATLANTIC LYL, SLYL, SLY LIBERTY SAVL AVCO EMBASSY DL LINDA LEE SBNL BANNER SML, SMML METROMEDIA BCL, SBCL BARCLAY PL, SPL MONUMENT BBC BBC MRL MUSHROOM SBTL BLUE THUMB SPGL PAGE ONE BL BRUNSWICK PML, SPML PARAMOUNT CBYL, SCBYL CARNABY SPFL PENNY FARTHING SCHL CHART PJL, SPJL PROJECT 3 SCYL CHRYSALIS RGL REG GRUNDY MCL CLARION RL REX NDL, SNDL, SNC COMMAND JL, SJL SCEPTER SCUL COMMONWEALTH UNITED SKL STAX CML, CML, CMC CONCERT-DISC SBL STEADY CL, SCL CORAL NL, SNL SUN DDL, SDDL DAFFODIL QL, SQL SUNSHINE SDJL DJM EL, SEL SPIN ZL, SZL DOT TRL, STRL TOP RANK DML, SDML DU MONDE TAL, STAL TRANSATLANTIC SDRL DURIUM TL, STL 20TH CENTURY-FOX EL EMBER UAL, SUAL, SUL UNITED ARTISTS EC, SEC, EL, SEL EVEREST SVHL VIOLETS HOLIDAY SFYL FANTASY VL VOCALION DL, SDL FESTIVAL SVL VOGUE FC FESTIVAL APL VOX FL, SFL FESTIVAL WA WALLIS GNPL, SGNPL GNP CRESCENDO APC, WC, SWC WESTMINSTER HVL, SHVL HISPAVOX SWWL WHITE WHALE SHWL HOT WAX IRL, SIRL IMPERIAL IL IMPULSE 2 Festival 30,000 LP series FL 30,001 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 1 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS FL 30,002 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 2 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS SFL 930,003 BRAZAN BRASS HENRY JEROME ORCHESTRA SEC 930,004 THE LITTLE TRAIN OF THE CAIPIRA LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SFL 930,005 CONCERTO FLAMENCO VINCENTE GOMEZ SFL 930,006 IRISH SING-ALONG BILL SHEPHERD SINGERS FL 30,007 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 1 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN FL 30,008 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 2 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN SCL 930,009 LIBERACE AT THE PALLADIUM LIBERACE RL 30,010 RENDEZVOUS WITH NOELINE BATLEY AUS NOELEEN BATLEY 6.61 30,011 30,012 RL 30,013 MORIAH COLLEGE JUNIOR CHOIR AUS ARR. -

Rough Draft of Essay Due: Nov 8 Second Draft Due: Dec 13 Third Draft Due: Jan 17

Week 6 Notes – 25 Oct 2017 A. Freewriting: 5 mins Think about what you’ve heard, tasted, smelled, seen, and touched today before this class. Write down as many of these images as you can, the best way you can, in the English words you know. Don’t worry about making proper sentences or following standard grammar. Imagine you are trying to make someone else feel exactly the way you felt, and write the words that you think will do that. B. Share models - grps of 3. Describe the essay you brought to share. Why do you like it? Do you plan on “stealing” any formal elements from it for your own essay? Which ones? C. Peer review of proposals - groups of 3 - Read your classmate’s proposal. - Write your name. Underneath, write: 1. one question you’d like to ask them about their essay 2. one suggestion/idea you have which might help them as they continue writing Discuss in groups. Schedule for your essay project: Rough draft of essay due: Nov 8 Second draft due: Dec 13 Third draft due: Jan 17 HW for next week (31 Oct 2017): Listening/Reading: This week I’d like to focus on a different genre of essay: a music review. I’d like you to read Lester Bangs’ review of the Van Morrison album Astral Weeks. It’s one of the most famous album reviews ever written, probably because it’s very passionate, subjective, and personal—qualities we don’t usually associate with art criticism. Before you read the review, you should listen to the Van Morrison album, which many people consider to be one of the greatest rock/pop albums of all time. -

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

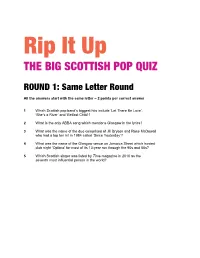

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

Murder of Innocents – the IRA Attack That Repulsed the World

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Murder of innocents – the IRA attack that HOME repulsed the world This article appears thanks to the Irish History (Diana Rusk, Irish News) News. Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The IRA bombing at a Remembrance Day commemoration in the Co Fermanagh town of Enniskillen 20 years ago this week killed 11 people, injured 63 and repulsed the world. Book Reviews & Book Forum Amateur video footage of the aftermath of the explosion on November 8 1987 was broadcast internationally, vividly Search / Archive portraying the suffering of innocent victims. Back to 10/96 Half were Presbyterians who had inadvertently stood the closest Papers to the hidden 40lb device so that they could be convenient to their place of worship. Reference There were three married couples – Wesley Armstrong (62) and wife Bertha (55), Billy Mullan (74) and wife Agnes (73), Kit About Johnston (71) and wife Jessie (62). The others who died were Sammy Gault (49), Ted Armstrong Contact (52), Johnny Megaw (67), Alberta Quinton (72) and the youngest victim, Marie Wilson (20). A 12th person, Ronnie Hill, who slipped into a coma days after the explosion, never woke up and died almost 14 years later. For the first time in the Troubles, the IRA admitted it had made a mistake, planting the device in a building owned by the Catholic church to, they said, target security forces patrolling the parade. The bombing is believed to be one of the watershed incidents of the Troubles largely because of the international outcry against the violence. -

What's It Like to Be Black and Irish?

“What’s it like to be black and Irish?” “Like a pint of Guinness.” The above quote is taken from an interview with Phil Lynott, the charismatic lead singer of the Celtic rock band Thin Lizzy, on Gay Byrne’s ‘The Late Late Show’. Lynott’s often playful and bold responses to such questions about his identity served to mask his overwhelming feelings of insecurity and ambivalent sense of belonging. As an illegitimate black child brought up in the 1950s in a strict Catholic family in Crumlin, a working-class district of Dublin, Lynott was seen to have a “paradoxical personality” (Bridgeman, qtd. in Thomson 4): his upbringing imbued him “with an acute sense of national and gender identity” (Smyth 39), yet his skin color and illegitimacy made him the target of racial and social abuse in a predominantly white and conservative Ireland. For Lynott, becoming a rockstar offered an opportunity to reinvent himself and be whoever he wanted to be. While he played up to the rock and roll lifestyle in which he was embedded, Lynott is often considered to have been a man trapped inside a caricature (Thomson 301). Geldof (qtd. in Putterford 182) believes that this rocker persona was Lynott’s ultimate downfall and led to his untimely death at just 36 years of age in 1986. For all his swagger and bravado, behind the mask, Lynott was a troubled, young man searching for a place to belong. While many books have been written about the life of Phil Lynott (e.g. Putterford; Lynott; Thomson), few have drawn attention to the notion of identity and the way in which music provided Lynott with an outlet to explore his self. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context.