C.O 03 P', I~ COCO F~F~ R~3~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glastonburyminiguide.Pdf

GLASTONBURY 2003 MAP Produced by Guardian Development Cover illustrations: John & Wendy Map data: Simmons Aerofilms MAP MARKET AREA INTRODUCTION GETA LOAD OF THIS... Welcome to Glastonbury 2003 and to the official Glastonbury Festival Mini-Guide. This special edition of the Guardian’s weekly TV and entertainments listings magazine contains all the information you need for a successful and stress-free festival. The Mini-Guide contains comprehensive listings for all the main stages, plus the pick of the acts at Green Fields, Lost and Cabaret Stages, and advice on where to find the best of the weird and wonderful happenings throughout the festival. There are also tips on the bands you shouldn’t miss, a rundown of the many bars dotted around the site, fold-out maps to help you get to grips with the 600 acres of space, and practical advice on everything from lost property to keeping healthy. Additional free copies of this Mini-Guide can be picked up from the Guardian newsstand in the market, the festival information points or the Workers Beer Co bars. To help you keep in touch with all the news from Glastonbury and beyond, the Guardian and Observer are being sold by vendors and from the newsstands at a specially discounted price during the festival . Whatever you want from Glastonbury, we hope this Mini-Guide will help you make the most of it. Have a great festival. Watt Andy Illustration: ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INFORMATION POINTS hygiene. Make sure you wash MONEY give a description. If you lose There are five information your hands after going to the loo The NatWest bank is near the your children, ask for advice points where you can get local, and before eating. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

KEEFUS CIANCIA (Discography)

KEEFUS CIANCIA 1/1/19 (Discography) Recording Album / Project Artist Credit Beyond the Palace Walls Paragon Taxi Piano, Keyboards (1993) Jazz in the Present Tense The Solsonics Keyboards (1993) Bop Gun Ice Cube Keyboards (1993) Fo Life Mack 10 Keyboards (1993) Cool Struttin The Pacific Jazz Alliance Keyboards (1994) Keyboards, Moog Synthesizer, N Gatz We Truss South Central Cartel (1994) Claves Nut-Meg Sez "Bozo the Town" Weapon of Choice Keyboards, Vocals (1994) Clavinet, Fender Rhodes, Moog Back to Reality Jeune (1995) Lead Highperspice Weapon of Choice Keyboards, Vocals (1996) I Am L.V. L.V. Keyboards (1996) Radio Odyssey Various Artists Keyboards (1996) The Jade Vincent Moy Producer, Composer, Musician (1996) Experiment Concepto Sol d'Menta Keyboards (1998) Nutmeg Phantasy Weapon of Choice Keyboards (1998) Whitey Ford Sings the Blues [Clean] Everlast Keyboards, Performer (1998) Another True Fiction Jerry Toback Moog Synthesizer (1999) Eat at Whitey's Everlast Bass, Keyboards, Band (2000) Loud Rocks Various Artists Keyboards (2000) Moog Synthesizer, Claves, You Know, for Kids Hate Fuck Trio (2000) Wurlitzer Synthesizer, Farfisa Organ, The ID Macy Gray (2001) Composer Motherland Natalie Merchant Piano, Keyboards (2001) Stimulated, Vol. 1 Various Artists Keyboards (2001) Diana Priscilla Ahn (2001) Organ, Keyboards, Clavinet, C'mon, C'mon Sheryl Crow (2002) String Samples Keyboards, Producer, Engineer, Soul of John Black The Soul of John Black (2003) Associate Producer Piano, Keyboards, Moog Thousand Kisses Deep Chris Botti (2003) Synthesizer, -

Popular Music Stuart Bailie a Troubles Archive Essay

popular music A Troubles Archive Essay Stuart Bailie Cover Image: Victor Sloan - Market Street, Derry From the collection of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland About the Author Stuart Bailie was on the staff of the NME (New Musical Express) from 1988 to 1996, rising to Assistant Editor in his last three years there. Since then, he has worked as a freelance journalist for Mojo, Uncut, Q, The Times, The Sunday Times and Hot Press. He has written sleevenotes for U2 and wrote the authorised story of Thin Lizzy, The Ballad Of The Thin Man in 1997. He has been presenting a BBC Radio Ulster show each Friday evening since 1999. He has been Associate Producer of several BBC TV music programmes, including the story of Ulster rock and pop: ‘So Hard To Beat’ in 2007. He has also been the scriptwriter / researcher for a series of BBC Radio 2 documentaries on U2, Thin Lizzy and Elvis Costello. Stuart is now CEO of Oh Yeah, a dedicated music centre in Belfast. Popular Music In September 1968 Van Morrison was in NewYork, recording a series of songs about life back in Belfast. This was his Astral Weeks album, one of his most important works. It was also a vivid snapshot of Northern Ireland just before the climate changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Troubles. In Morrison’s sentimental picture, there were youthful voices, parties and high-spirits; flamboyant figures such as Madame George cruised the streets of Belfast as the post-war generation challenged social conventions. The hippy ideals were already receding in America, but Belfast had experienced a belated Summer of Love and a blossoming social life. -

TECHNEWS Words: MICK WILSON

TECHNEWS words: MICK WILSON 138 TECH TALK — MANU GONZALEZ The Ibiza-based DJ/producer talks about how the island helped launch his tech voyage. DIGITAL LOVE 141 IN THE With the release of four new digital STUDIO products from Denon, has a new era We hear about French producer for DJs dawned? Vitalic’s studio gear. t’s undeniable that 2016 saw some pretty seismic shifts. Except, perhaps, in the DJ technology community. We kept on doing what we did with the I same old, same old. However, the new year may hold some surprises. We can now reveal a potential game- changer in the world of DJ technology, with the release of Denon DJ’s new DJ gear. Four new products aim to confront the dominance of Pioneer DJ in the booth: the SC5000 media player, Engine Prime music management system, X1800 mixer and the VL12 turntable. We suppose the biggest announcement was the new Denon 140 808 STATE DJ SC5000 Multimedia Player. When we first saw it, we Is Roland’s new DJ-808 controller were impressed by the way it looked, even before we had a set to become legendary? chance to get hands-on and find out what it could do. The DJ Mag Tech crew were amongst the first people to ever see and touch this array of new DJ technology. We welcomed it — after all, whilst there has been a cycle of industry standards over the years, there have only really been two periods of dominance without anything else really making a dent. Technics had its 1200s and Pioneer DJ had its CDJs; many tried to buck the trend but fell by the wayside. -

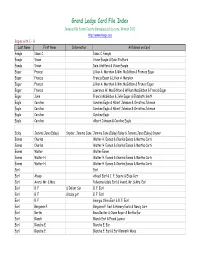

Grand Ledge Card File Index

Grand Ledge Card File Index Indexed By Eaton County Genealogical Society, Winter 2010 http://www.miegs.org Begins with E - H Last Name First Name Information All Names on Card Eaegle Isaac C. Isaac C. Eaegle Eaegle Vivian Vivian Eaegle & Dale Stafford Eaegle Vivian Dale Stafford & Vivian Eaegle Eager Frances Lillian A. Mershon & Wm. McGibbon & Frances Eager Eager Francis Francis Eager & Lillian A. Mershon Eager Francis Lillian A. Mershon & Wm. McGibbon & Francis Eager Eager Francis Lawrence W. MacGibbon & William MacGibbon & Francis Eager Eager John Francis McGibbon & John Eager & Elizabeth Smith Eagle Caroline Caroline Eagle & Albert Johnson & Christina Johnson Eagle Caroline Caroline Eagle & Albert Johnson & Christina Johnson Eagle Caroline Caroline Eagle Eagle Caroline Albert Johnson & Caroline Eagle Ealey Jemima Jane (Ealey) Snyder, Jemima Jane Jemima Jane (Ealey) Ealey & Jemima Jane (Ealey) Snyder Eames Charles Walter H. Eames & Charles Eames & Martha Curtis Eames Charles Walter H. Eames & Charles Eames & Martha Curtis Eames Walter Walter Eames Eames Walter H. Walter H. Eames & Charles Eames & Martha Curtis Eames Walter H. Walter H. Eames & Charles Eames & Martha Curtis Earl Earl Earl Abigail Abigail Earl & J. F. Squire & Eliza Carr Earl Avord, Mr. & Mrs. Pollyanna Udela Earl & Avord, Mr. & Mrs. Earl Earl B. F. & Infant Son B. F. Earl Earl B. F. & baby girl B. F. Earl Earl B. F. Georgia Olivia Earl & B. F. Earl Earl Benjamin F. Benjamin F. Earl & Henery Earle & Nancy Carr Earl Bertha Reva Baxter & Owen Boyer & Bertha Earl Earl Blanch Blanch Earl & Frank Lunore Earl Blanche E. Blanche E. Earl Earl Blanche E. Blanche E. Earl & Earl Kenneth Wood Earl Blanche E. -

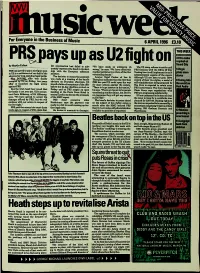

Music-Week-1996-04-0

• ^ music we For Everyone in the Business of Music 6 APRIL1996 £3 THISWEEK PRS pays up as U2fight on by Martin Talbot The U2 camp refuses to settle until PRS bas agreed to ings with the European collection s. "We 1 seofthefctively TradingPRS finalises how it with will implementthe Office theOf Fairself- adverearies' long-standingtlement of one légal half battle. of the societies.The décision to accept the payment outstanding i administration aspects of the report. 4a^,...£400.QQÛ^offer_ was finaUy was made at a meeting of the band's ThompsonLawyer indicatesNigel Parker that the of factLee that & controlAlthough of theirU2 are live keen rights, to gaina model 100% of alleracceptèa it byH0â'onlaunched Friday,its légal two actionyears issuedadvisors a letteron Thursday of acceptance aflernoon. of the offer U2 PRS has paid U2 could open the way self-administration being proposed by against PRS. before the 21-day deadline arrived on "There " t the society. PRSThe Cureinvolvement. is expected The toCure retain manager some theBut battle the isIrish not overband yet. bas im vowed accoun- that meetingFriday and at theas PRSForte stagedCrest Hôtelan open in he says. "There are bound to be people Chris Parry says negotiations with tant Ossie Kilkenny, of OJ Kilkenny, central London to discuss the proposais )msidering guarantee similar they will claims, get anybut theimoi PRS are ïprogressing understood satisfactorily.to be keen to clear damagessays, "We offered bave agreedby PRS, to but accept we willthe oftheMMC report. itofPRS." the isi ne for worldwii HutchinsonPRS chief says theexecutive payment Johnwas theplanned tour arefor expected1997-98. -

SBS Chill 12:00 AM Sunday, 23 December 2018 Start Title Artist 00:08 Shelter A.J

SBS Chill 12:00 AM Sunday, 23 December 2018 Start Title Artist 00:08 Shelter A.J. Heath 03:41 Teranga - Bah Catrin Finch & Seckou Kei... 09:35 We're Going Home Clint Mansell 13:22 A Forgotten Promise The Zero Project 17:08 Diamente Blue States 21:35 Endless Summer Flanger 26:58 Declaration of love (pianomix) Noise Boyz feat. Io Vita 32:08 For Her Smile (Epilogue) Butch 41:55 Walls Jinja Safari 45:52 Far Away (2014 Remix) All India Radio 52:38 The Spoils (feat. Hope Sandoval) Massive Attack 58:16 Ask For A Kiss Pepe Deluxe Powergold Music Scheduling Total Time In Hour: 63:01 Total Music In Hour: 62:29 Licensed to SBS SBS Chill 1:00 AM Sunday, 23 December 2018 Start Title Artist 00:07 The Night of the Sultans (le voyage ethno mix) Sean Hayman 05:39 The Sun Won't Set (Featuring Norah Jones) Anoushka Shankar & Nora... 09:14 Magicman Bonobo 13:56 Ho Renomo Cluster & Eno 18:50 Paradisum William Orbit 22:27 I see you Dickie Burkhard Dallwitz, Erkki V... 26:33 Clipper ISAN 30:09 Storm Returns (A Prefuse/Tommy Guerrero Interlude) Prefuse 73 35:25 Unfinished Business Lounge Conjunction 42:09 Zen Garden Masakazu Yoshizawa 45:13 Autumn's Back Chill Air 49:55 Babies Colleen 53:21 Already Replaced Steve Hauschildt 57:25 Reciever Tycho Powergold Music Scheduling Total Time In Hour: 61:40 Total Music In Hour: 61:09 Licensed to SBS SBS Chill 2:00 AM Sunday, 23 December 2018 Start Title Artist 00:06 Easier Mansionair 04:29 Moth to the Flame Gorodisch 08:17 Moog Island Morcheeba 11:47 Spaceships Hi-Fi Companions 17:37 Big Sky (acoustic mix) John O'Callaghan/Audrey .. -

Universitá Degli Studi Di Milano Facoltà Di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche E Naturali Dipartimento Di Tecnologie Dell'informazione

UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE, FISICHE E NATURALI DIPARTIMENTO DI TECNOLOGIE DELL'INFORMAZIONE SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO IN INFORMATICA Settore disciplinare INF/01 TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA CICLO XXIII SERENDIPITOUS MENTORSHIP IN MUSIC RECOMMENDER SYSTEMS Eugenio Tacchini Relatore: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Direttore della Scuola di Dottorato: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Anno Accademico 2010/2011 II Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the people who helped me during my Ph.D. First of all I would like to thank Prof. Ernesto Damiani, my advisor, not only for his support and the knowledge he imparted to me but also for his capacity of understanding my needs and for having let me follow my passions; thanks also to all the other people of the SESAR Lab, in particular to Paolo Ceravolo and Gabriele Gianini. Thanks to Prof. Domenico Ferrari, who gave me the possibility to work in an inspiring context after my graduation, helping me to understand the direction I had to take. Thanks to Prof. Ken Goldberg for having hosted me in his laboratory, the Berkeley Laboratory for Automation Science and Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, a place where I learnt a lot; thanks also to all the people of the research group and in particular to Dmitry Berenson and Timmy Siauw for the very fruitful discussions about clustering, path searching and other aspects of my work. Thanks to all the people who accepted to review my work: Prof. Richard Chbeir, Prof. Ken Goldberg, Prof. Przemysław Kazienko, Prof. Ronald Maier and Prof. Robert Tolksdorf. Thanks to 7digital, our media partner for the experimental test, and in particular to Filip Denker. -

Speaking Activities for the Classroom

Speaking Activities for the Classroom Copyright 2004 Compiled by David Holmes . Contents Preface : To The Teacher Chapter One : Warm-up Activities Chapter Two : Words, Phrases and Sentences Chapter Three : Grammar and Speaking Chapter Four : Interactive Role-Play Chapter Five : Traveling and Touring Chapter Six : Finding the Right Words Chapter Seven : Fables, Tales and Stories Chapter Eight : Talking Tasks Chapter Nine : A Bit of Business Chapter Ten : Pronunciation Chapter Eleven : How to Improve Your Diction Chapter Twelve : Sound and Rhythm Chapter Thirteen : More Pronunciation Practice Chapter Fourteen : Curriculum Development . 3 Preface The materials in this text were compiled over a period of ten years, in Thailand from 1993 to 2003, while I was teaching at The Faculty of Arts at Chulalongkorn University and later at the Department of Language at KMUTT. I started a file of speaking activities because there were too many tasks and ideas to keep in my head, and I wanted to be able to access them when I needed them in the future. Eventually, the file grew thicker and thicker, until it was big enough to become a book. The speaking activities in this text come from a variety of sources: A lot of the tasks sprang from my own imagination, stimulating me to go into the classroom, feeling motivated by the freshness that accompanies a new inspiration and being eager to share it with my students. This could be compared to cooking on impulse rather than following a set recipe. I got many additional ideas from talking to fellow- teachers about what worked for them in their classes. -

Popular Viennese Electronic Music, 1990–2015 a Cultural History

Popular Viennese Electronic Music, 1990–2015 A Cultural History Ewa Mazierska First published 2019 ISBN: 978-1-138-71391-8 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-23062-7 (ebk) 4 Kruder and Dorfmeister The studio(us) remixers (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) First published 2019 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Ewa Mazierska The right of Ewa Mazierska to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. With the exception of Chapter 4 and 8, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Chapter 4 and 8 of this book is available for free in PDF format as Open Access from the individual product page at www.routledge.com. It has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 license. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mazierska, Ewa, author. -

Keefus Ciancia

KEEFUS CIANCIA COMPOSER Invariably pushing music to places beyond the norm, veering flawlessly in and out of contrasting musical genres, Keefus Ciancia has worked as a composer and producer on numerous standout productions, including the BAFTA and Emmy award winning Killing Eve and True Detective, The Fall, Strangerland, The Ladykillers and London Spy. Keefus and co-composer David Holmes won the BAFTA Original Music Award in 2019 for their score to Killing Eve and their music has recently been nominated a second time in the BAFTA 2020 Awards. They also received an Ivor Novello in 2016 for Best Television Soundtrack for their score on the TV series, London Spy. Keefus was nominated for an Emmy for True Detective in 2019 and also received an Emmy nomination for his work with Everlast for co-writing and producing the theme song for the hit television series Saving Grace. Keefus is a pianist, raised playing classical music yet influenced by two older musician brothers who broadened his listening palette to a wild, eclectic array of sounds forming his love and attraction to film scores early on. He moved to Los Angeles and began to work with Lonnie "Meganut" Marshall from LA’s underground scene of burgeoning bands. Marshall and Ciancia started the multi genre experimental group ‘Weapon Of Choice’ that flourished for three albums. During that time, he recorded for the West Coast hip-hop scene with artists Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, South Central Cartel and E40. In the early nineties, Keefus met singer Jade Vincent and together they formed their own 10-piece experimental film-noir big band, ‘The Jade Vincent Experiment’ later to become Vincent & Mr.